Society and Science: Ancient Astronomy. Joshua J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BABYLONIAN ASTRONOMY* by W.M. O'neil Though the Modern Western

o BABYLONIAN ASTRONOMY* By W.M. O'Neil Though the modern western world had heard of the Chaldaeans in the Old Testament as soothsayers and astrologers and students of Hellenistic astronomy knew of references to Babylonian observations of eclipses and the like, it is only during the last three quarters of a century but especially during the last half century that modern scholars, following the decipherment of the cuneiform writing on clay tablets, have begun to reveal the richness of Babylonian astronomy. They have, however, a long way yet to go. First, only a fraction of the materials scattered throughout the western world have been studied and interpreted. Fragments of the one tablet are sometimes in different museums; this adds to the difficulty. Second, the materials are usually fragmentary: a few pages torn from a book as it were or even only a few parts of pages (See Plate 1). Otto Neugebauer, perhaps the greatest scholar recently working on Babylonian astronomy, says that it is impossible yet to write an adequate history of Babylonian astronomy and suggests that it may never be possible. How many of the needed basic texts have crumbled into dust after acquisition by small museums unable to give them the needed care? , how many are lying unstudied in the multitudinous collections in the Middle East, in Europe and in North America? or are still lying in the ground?, are questions to which the answers are unknown. Nevertheless, through the work of Neugebauer, his predecessors and younger scholars taking over from him, some outlines of the history and the methods of Babylonian astronomy are becoming clearer. -

Astronomy and Its Instruments Before and After Galileo

INTERNATIONAL ASTRONOMICAL UNION INAF ASTRONOMICAL OBSERVATORY OF PADOVA, ITALY ASTRONOMY AND ITS INSTRUMENTS BEFORE AND AFTER GALILEO Proceedings of the Joint Symposium held in Venice, San Servolo Island, Italy 28 September - 2 October 2009 Edited by LUISA PIGATTO and VALERIA ZANINI CONTENTS Preface xm OPENING CEREMONY WELCOME ADDRESSES KAREL A. VAN DER HUCHT, Opening address on behalf of the International Astronomical Union 3 ENRICO CAPPELLARO, INAF Osservatorio Astronomico di Padova, Italy, welcome address 5 SESSION 1 GALILEO AND HIS TIME THE VENETIAN CULTURAL ENVIRONMENT Chair: Il-Seong Nha GINO BENZONI, Culture and Science in Venice and Padova between the end of 16th and the beginning of 17th century (in Italian) 9 MICHELA DAL BORGO, The Arsenal of Venice at Galileo's time 29 LUISA PIGATTO, Galileo and Father Paolo. The improvement of the telescope 37 MAURO D'ONOFRIO AND CARLO BURIGANA, Questions of modern cosmology: a book to celebrate Galileo 51 SESSION 2 ASTRONOMY AND WORLD HERITAGE INITIATIVE Chair: Gudrun Wolfichmidt CLIVE RUGGLES, Implementing the Astronomy and World Heritage Initiative 65 KAREL A. VAN DER HUCHT, Memorandum of Understanding between the International Astronomical Union and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization on Astronomy and World Heritage 69 VIII CONTENTS ILEANA CHINNICI, Archives and Astronomical Heritage 77 LUISA PIGATTO, Astronomical Instruments and World Heritage 81 GUDRUN WOLFSCHMIDT, Acknowledging the cultural and scientific values of properties connected with astronomy - observatories from the Renaissance to the 20th century 85 SESSION 3 ASTRONOMICAL STRUCTURES THROUGH THE AGES FROM STONE MONUMENTS TO MODERN OBSERVATORIES Chair: Clive Ruggles GEORG ZOTTI, Astronomical orientation of neolithic circular ditch systems (Kreisgrabenanlagen) 91 YONG BOK LEE, The alignment of dolmens and cup-marks on capstone as star map at Haman area in Korea 101 IL-SEONG NHA AND SARAH L. -

3.02 Base of a Bronze Statuette May Osiris-Iah-Thoth Give Life, Prosperity and Health to Padiwesir, Son of Udjahekau, Born of the Lady of the Bronze

01 Part 1-3/S. 1-249/korr.drh 04.08.2006 16:00 Uhr Seite 171 Late Period, Ptolemaic and Roman Periods 171 been found in this hollow space. Often the space is not many thousands of animal mummies laid to rest in nearly large enough to contain a complete animal underground catacombs at this time – what to us is a mummy, so a relic consisting of only a few bones had to rather bizarre custom served to ensure a personal con- suffice. These relic holders served the same aim as the tact between the god and man. MJR 3.02 Base of a bronze statuette May Osiris-Iah-Thoth give life, prosperity and health to Padiwesir, son of Udjahekau, born of the lady of the Bronze. house, the lay priestess of Mut, Iriru”. The title given to Late Period, Dynasty 25–26, c.712–525BC. the mother is quite rare; its literal meaning is “follower” H. 2.4cm, W. 4.5cm, D. 5.7cm. or “female servant” of Mut; women with this title appear to have served as a kind of unofficial, uncanon- ical priestesses in the temple of the goddess Mut in Kar- This hollow rectangular base is all that is left of what nak.2 They are chiefly known from a number of bronze was once a statuette of Osiris-Iah-Thoth, a lunar form 1 mirrors which played an important part in certain ritu- of the god Osiris. The appearance of the god would in als connected with Mut. The title is attested only from all essential aspects have been the same as our no.3.16: the time of Dynasties 25 and 26. -

Babylonian Astral Science in the Hellenistic World: Reception and Transmission

CAS® e SERIES Nummer 4 / 2010 Francesca Rochberg (Berkeley) Babylonian Astral Science in the Hellenistic World: Reception and Transmission Herausgegeben von Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München Center for Advanced Studies®, Seestr. 13, 80802 München www.cas.lmu.de/publikationen/eseries Nummer 4 / 2010 Babylonian Astral Science in the Hellenistic World: Reception and Transmission Francesca Rochberg (Berkeley) In his astrological work the Tetrabiblos, the astronomer such as in Strabo’s Geography, as well as in an astrono- Ptolemy describes the effects of geography on ethnic mical text from Oxyrhynchus in the second century of character, claiming, for example, that due to their specific our era roughly contemporary with Ptolemy [P.Oxy. geographical location „The ...Chaldeans and Orchinians 4139:8; see Jones 1999, I 97-99 and II 22-23]. This have familiarity with Leo and the sun, so that they are astronomical papyrus fragment refers to the Orchenoi, simpler, kindly, addicted to astrology.” [Tetr. 2.3] or Urukeans, in direct connection with a lunar parameter Ptolemy was correct in putting the Chaldeans and identifiable as a Babylonian period for lunar anomaly Orchinians together geographically, as the Chaldeans, or preserved on cuneiform tablets from Uruk. The Kaldayu, were once West Semitic tribal groups located Babylonian, or Chaldean, literati, including those from in the parts of southern and western Babylonia known Uruk were rightly famed for astronomy and astrology, as Kaldu, and the Orchinians, or Urukayu, were the „addicted,” as Ptolemy put it, and eventually, in Greco- inhabitants of the southern Babylonian city of Uruk. He Roman works, the term Chaldean came to be interchan- was also correct in that he was transmitting a tradition geable with „astrologer.” from the Babylonians themselves, which, according to a Hellenistic Greek writers seeking to claim an authorita- Hellenistic tablet from Uruk [VAT 7847 obv. -

Geminos and Babylonian Astronomy

Geminos and Babylonian astronomy J. M. Steele Introduction Geminos’ Introduction to the Phenomena is one of several introductions to astronomy written by Greek and Latin authors during the last couple of centuries bc and the first few centuries ad.1 Geminos’ work is unusual, however, in including some fairly detailed—and accurate—technical information about Babylonian astronomy, some of which is explicitly attributed to the “Chal- deans.” Indeed, before the rediscovery of cuneiform sources in the nineteenth century, Gem- inos provided the most detailed information on Babylonian astronomy available, aside from the reports of several eclipse and planetary observations quoted by Ptolemy in the Almagest. Early-modern histories of astronomy, those that did not simply quote fantastical accounts of pre-Greek astronomy based upon the Bible and Josephus, relied heavily upon Geminos for their discussion of Babylonian (or “Chaldean”) astronomy.2 What can be learnt of Babylonian astron- omy from Geminos is, of course, extremely limited and restricted to those topics which have a place in an introduction to astronomy as this discipline was understood in the Greek world. Thus, aspects of Babylonian astronomy which relate to the celestial sphere (e.g. the zodiac and the ris- ing times of the ecliptic), the luni-solar calendar (e.g. intercalation and the 19-year (“Metonic”) cycle), and lunar motion, are included, but Geminos tells us nothing about Babylonian planetary theory (the planets are only touched upon briefly by Geminos), predictive astronomy that uses planetary and lunar periods, observational astronomy, or the problem of lunar visibility, which formed major parts of Babylonian astronomical practice. -

The Routledge Dictionary of Egyptian Gods and Goddesses

The Routledge Dictionary of Egyptian Gods and Goddesses The Routledge Dictionary of Egyptian Gods and Goddesses provides one of the most comprehensive listings and descriptions of Egyptian deities. Now in its second edition, it contains: ● A new introduction ● Updated entries and four new entries on deities ● Names of the deities as hieroglyphs ● A survey of gods and goddesses as they appear in Classical literature ● An expanded chronology and updated bibliography ● Illustrations of the gods and emblems of each district ● A map of ancient Egypt and a Time Chart. Presenting a vivid picture of the complexity and richness of imagery of Egyptian mythology, students studying Ancient Egypt, travellers, visitors to museums and all those interested in mythology will find this an invaluable resource. George Hart was staff lecturer and educator on the Ancient Egyptian collections in the Education Department of the British Museum. He is now a freelance lecturer and writer. You may also be interested in the following Routledge Student Reference titles: Archaeology: The Key Concepts Edited by Colin Renfrew and Paul Bahn Ancient History: Key Themes and Approaches Neville Morley Fifty Key Classical Authors Alison Sharrock and Rhiannon Ash Who’s Who in Classical Mythology Michael Grant and John Hazel Who’s Who in Non-Classical Mythology Egerton Sykes, revised by Allen Kendall Who’s Who in the Greek World John Hazel Who’s Who in the Roman World John Hazel The Routledge Dictionary of Egyptian Gods and Goddesses George Hart Second edition First published 2005 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 270 Madison Ave, New York, NY 10016 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. -

The Adaptation of Babylonian Methods in Greek Numerical Astronomy

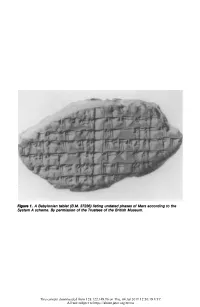

FIgure 1. A Babylonian tablet (B.M. 37236) listing undated phases of Mars according to the System A scheme. By permission of the Trustees of the British Museum. This content downloaded from 128.122.149.96 on Thu, 04 Jul 2019 12:50:19 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms The Adaptation of Babylonian Methods in Greek Numerical Astronomy By Alexander Jones* THE DISTINCTION CUSTOMARILY MADE between the two chief astro- nomical traditions of antiquity is that Greek astronomy was geometrical, whereas Babylonian astronomy was arithmetical. That is to say, the Babylonian astronomers of the last five centuries B.C. devised elaborate combinations of arithmetical sequences to predict the apparent motions of the heavenly bodies, while the Greeks persistently tried to explain the same phenomena by hypothe- sizing kinematic models compounded out of circular motions. This description is substantially correct so far as it goes, but it conceals a great difference on the Greek side between the methods of, say, Eudoxus in the fourth century B.C. and those of Ptolemy in the second century of our era. Both tried to account for the observed behavior of the stars, sun, moon, and planets by means of combinations of circular motions. But Eudoxus seems to have studied the properties of his models purely through the resources of geometry. The only numerical parameters associated with his concentric spheres in our ancient sources are crude periods of synodic and longitudinal revolution, that is to say, data imposed on the models rather than deduced from them.1 By contrast, Ptolemy's approach in the Alma- 2 gest is thoroughly numerical. -

Beginnings of Indian Astronomy with Reference to a Parallel Development in China

History of Science in South Asia A journal for the history of all forms of scientific thought and action, ancient and modern, in all regions of South Asia Beginnings of Indian Astronomy with Reference to a Parallel Development in China Asko Parpola University of Helsinki MLA style citation form: Asko Parpola, “Beginnings of Indian Astronomy, with Reference to a Parallel De- velopment in China” History of Science in South Asia (): –. Online version available at: http://hssa.sayahna.org/. HISTORY OF SCIENCE IN SOUTH ASIA A journal for the history of all forms of scientific thought and action, ancient and modern, in all regions of South Asia, published online at http://hssa.sayahna.org Editorial Board: • Dominik Wujastyk, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria • Kim Plofker, Union College, Schenectady, United States • Dhruv Raina, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, India • Sreeramula Rajeswara Sarma, formerly Aligarh Muslim University, Düsseldorf, Germany • Fabrizio Speziale, Université Sorbonne Nouvelle – CNRS, Paris, France • Michio Yano, Kyoto Sangyo University, Kyoto, Japan Principal Contact: Dominik Wujastyk, Editor, University of Vienna Email: [email protected] Mailing Address: Krishna GS, Editorial Support, History of Science in South Asia Sayahna, , Jagathy, Trivandrum , Kerala, India This journal provides immediate open access to its content on the principle that making research freely available to the public supports a greater global exchange of knowledge. Copyrights of all the articles rest with the respective authors and published under the provisions of Creative Commons Attribution- ShareAlike . Unported License. The electronic versions were generated from sources marked up in LATEX in a computer running / operating system. was typeset using XƎTEX from TEXLive . -

The Short History of Science

PHYSICS FOUNDATIONS SOCIETY THE FINNISH SOCIETY FOR NATURAL PHILOSOPHY PHYSICS FOUNDATIONS SOCIETY THE FINNISH SOCIETY FOR www.physicsfoundations.org NATURAL PHILOSOPHY www.lfs.fi Dr. Suntola’s “The Short History of Science” shows fascinating competence in its constructively critical in-depth exploration of the long path that the pioneers of metaphysics and empirical science have followed in building up our present understanding of physical reality. The book is made unique by the author’s perspective. He reflects the historical path to his Dynamic Universe theory that opens an unparalleled perspective to a deeper understanding of the harmony in nature – to click the pieces of the puzzle into their places. The book opens a unique possibility for the reader to make his own evaluation of the postulates behind our present understanding of reality. – Tarja Kallio-Tamminen, PhD, theoretical philosophy, MSc, high energy physics The book gives an exceptionally interesting perspective on the history of science and the development paths that have led to our scientific picture of physical reality. As a philosophical question, the reader may conclude how much the development has been directed by coincidences, and whether the picture of reality would have been different if another path had been chosen. – Heikki Sipilä, PhD, nuclear physics Would other routes have been chosen, if all modern experiments had been available to the early scientists? This is an excellent book for a guided scientific tour challenging the reader to an in-depth consideration of the choices made. – Ari Lehto, PhD, physics Tuomo Suntola, PhD in Electron Physics at Helsinki University of Technology (1971). -

The Constellations of the Egyptian Astronomical Diagrams

The Constellations of the Egyptian Astronomical Diagrams Gyula Priskin University of Szeged EPICTIONS OF THE constellations that the ancient Egyptians observed in the sky first appeared on some coffin lids at the beginning of the 2nd millenium BCE, as inserts into the tables that listed the names of the asterisms signalling the night hours D 1 (decans). These early sources only include the representations of four constellations, two in the northern sky, and two in its southern regions: the goddess Nut (Nw.t) holding up the sky hieroglyph, the Foreleg (msḫt.jw), belonging to Seth according to later descriptions, the striding figure of Sah (sȝḥ), the celestial manifestation of Osiris, and the standing goddess of Sopdet (spd.t), who is often associated with Isis [fig. 1].2 The last three kept being shown in later documents, while the first one disappeared completely after the Middle Kingdom.3 A more detailed visual catalogue of the constellations has come down to us in the form of the astronomical diagrams that were first recorded at the beginning of the New Kingdom,4 though these diagrams very possibly existed earlier, as a fragmented and now lost specimen seems to indicate.5 Although their particular elements vary to a certain degree, these astronomical diagrams continued to be depicted on tomb ceilings, water clocks, temple surfaces, and coffins well into Graeco-Roman times. When towards the end of the first millenium BCE the Egyptians started to represent the zodiacal signs on their monuments, these zodiacs also included the figures of the most salient constellations.6 It should be noted, however, that according to certain decanal names,7 and the relevant entries in Amenemipet’s onomasticon (Ramesside Period),8 the Egyptians knew some further constellations for which apparently no pictorial records have survived. -

La Lactancia En El Antiguo Egipto: Una Aproximación Léxica Y Cultural

TESIS DOCTORAL LA LACTANCIA EN EL ANTIGUO EGIPTO: UNA APROXIMACIÓN LÉXICA Y CULTURAL SARA RODRÍGUEZ-BERZOSA GÓMEZ-LANDERO Director: DR. MARC ORRIOLS I LLONCH Codirector: DR. JORDI CORS I MEYA Doctorado en Egiptología Institut d`Estudis del Pròxim Orient Antic Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona Barcelona 2016 2.150. Fuente: Remedio 836, pEbers 97, 10-11. Texto en jeroglífico: → Transliteración: → Int irtt n mnat Sdt Xrd iAt nt aHA snwH Hr mrHt gs iAt=s im(=s). Traducción: Traer la leche de una nodriza-menat que amamanta a un niño: escama de perca hervir con aceite, untar su piel con (ella). Datación: Procedencia: Finales de la Dinastía XVII, Segundo Tebas. Período Intermedio. Tipo de escritura: Soporte: Hierática. Papiro. Género del texto: Contexto: Mágico-médico. Remedio para la mujer. Edición utilizada: Otras ediciones: WRESZINSKI, 1913: 201. No se han encontrado otras ediciones. Traducciones: BARDINET: Ramener le lait à une nourrice que tète n enfant: èpine dorsale d`un poisson-combattant. (Ce) será bouilli dans la graisse/huile. Enduire avec (cela) son (=de la nourrice) dos2213. Bibliografía: BARDINET, 1995. WRESZINSKI, 1913: 201. Comentario: Algunos papiros mágico-médicos contienen métodos para estimular la producción de leche, donde se incluyen pruebas para ayudar a reconocer si la leche era buena o mala. En este caso el ingrediente necesario es la leche de una nodriza-menat. 2213 BARDINET, 1995: 450. 820 821 2.151. Fuente: Ataúd de Rey, Museo Egipcio del Cairo, CGC 61004. Texto en jeroglífico2214: Transliteración: Wsir (xr) mnat nt Hmt-nTr IaH-ms-nfrtiry mAat xrw Rai. Traducción: Osiris (ante) la nodriza-menat de la esposa del dios Ahmose-Nefertari, justificada de voz, Rey. -

The Stunning Orion Nebula FREE SHIPPING to Anywhere in Canada, All Products, Always KILLER VIEWS of PLANETS

The Journal of The Royal Astronomical Society of Canada PROMOTING ASTRONOMY IN CANADA October/octobre 2011 Volume/volume 105 Le Journal de la Société royale d’astronomie du Canada Number/numéro 5 [750] Inside this issue: Decans, Djed Pillars, and Seasonal-Hours in Ancient Egypt Astronomy Outreach in Cuba: Trip Two Discovery of the Expansion of the Universe Palomar Oranges To See the Stars Anew The stunning Orion Nebula FREE SHIPPING To Anywhere in Canada, All Products, Always KILLER VIEWS OF PLANETS CT102 NEW FROM CANADIAN TELESCOPES 102mm f:11 Air Spaced Doublet Achromatic Fraunhoufer Design CanadianTelescopes.Com Largest Collection of Telescopes and Accessories from Major Brands VIXEN ANTARES MEADE EXPLORE SCIENTIFIC CELESTRON CANADIAN TELESCOPES TELEGIZMOS IOPTRON LUNT STARLIGHT INSTRUMENTS OPTEC SBIG TELRAD HOTECH FARPOINT THOUSAND OAKS BAADER PLANETRAIUM ASTRO TRAK ASTRODON RASC LOSMANDY CORONADO BORG QSI TELEVUE SKY WATCHER . and more to come October/octobre 2011 | Vol. 105, No. 5 | Whole Number 750 contents / table des matières Feature Articles / Articles de fond Columns / Rubriques 187 Decans, Djed Pillars, and Seasonal-Hours in 205 Cosmic Contemplations: Widefield Astro Imaging Ancient Egypt with the new Micro 4/3rds Digital Cameras by William W. Dodd by Jim Chung 195 Astronomy Outreach in Cuba: Trip Two 209 On Another Wavelength: M56—A Globular by David M.F. Chapman Cluster in Lyra by David Garner 197 Discovery of the Expansion of the Universe by Sidney van den Bergh 210 The Affair of the Sir Adam Wilson Telescope, Societal Negligence, and the Damning Miller Report 199 Palomar Oranges by R.A. Rosenfeld by Ken Backer 214 Second Light: A Conference to Remember 199 To See the Stars Anew by Leslie J.