Understanding Market Drivers in Syria 2 Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE PUBLIC MONETARY AUTHORITY in NORTHWEST SYRIA Flash Report 10 July 2020 KEY DEVELOPMENTS

THE PUBLIC MONETARY AUTHORITY IN NORTHWEST SYRIA Flash report 10 July 2020 KEY DEVELOPMENTS The Public Monetary Authority (PMA) is a rebranding of the Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham (HTS)'s General Institution for Cash Management and Customer Protection (CMCP) which was established in May 2017. The PMA imposed a mandatory registration on currency exchange and hawala companies and classified them into three main categories depending on the size of their financial capital. The PMA has the right to supervise, monitor, and inspect monetary transactions, data, records and documents of licensed companies to ensure compliance with the PMA’s regulations, during the validity period of the license, or even if the license was terminated or revoked. Licensed companies must provide the PMA with a monthly report detailing incoming and outcoming financial remittances and must maintain financial liquidity ranging from 25% to 50% of the company's financial value in US dollars at the PMA custody at all times. Financial transfers made in Turkish lira will include the Syrian Salvation Government (SSG), as the currency will be brought in from the SSG's Sham Bank. This is not the case of financial transfers made in other currencies including the US dollar. The intervention of the PMA in hawala networks has profound implications for humanitarian organizations operating in northwestern Syria, however hawala agents, particularly in medium to large agencies, can reject the PMA's monitoring and control requirements. INTRODUCTION constant price fluctuation", according to interviews To mitigate the impact of the rapid and continuous published on local media agencies. collapse of the Syrian pound, which exceeded 3,000 SYP per USD in early July 2020, local authorities in Local authorities however have not explained the northwest Syria have decided instead to trade political aspect of this shift with regards to its effect using the Turkish lira. -

Policy Notes for the Trump Notes Administration the Washington Institute for Near East Policy ■ 2018 ■ Pn55

TRANSITION 2017 POLICYPOLICY NOTES FOR THE TRUMP NOTES ADMINISTRATION THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ 2018 ■ PN55 TUNISIAN FOREIGN FIGHTERS IN IRAQ AND SYRIA AARON Y. ZELIN Tunisia should really open its embassy in Raqqa, not Damascus. That’s where its people are. —ABU KHALED, AN ISLAMIC STATE SPY1 THE PAST FEW YEARS have seen rising interest in foreign fighting as a general phenomenon and in fighters joining jihadist groups in particular. Tunisians figure disproportionately among the foreign jihadist cohort, yet their ubiquity is somewhat confounding. Why Tunisians? This study aims to bring clarity to this question by examining Tunisia’s foreign fighter networks mobilized to Syria and Iraq since 2011, when insurgencies shook those two countries amid the broader Arab Spring uprisings. ©2018 THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ NO. 30 ■ JANUARY 2017 AARON Y. ZELIN Along with seeking to determine what motivated Evolution of Tunisian Participation these individuals, it endeavors to reconcile estimated in the Iraq Jihad numbers of Tunisians who actually traveled, who were killed in theater, and who returned home. The find- Although the involvement of Tunisians in foreign jihad ings are based on a wide range of sources in multiple campaigns predates the 2003 Iraq war, that conflict languages as well as data sets created by the author inspired a new generation of recruits whose effects since 2011. Another way of framing the discussion will lasted into the aftermath of the Tunisian revolution. center on Tunisians who participated in the jihad fol- These individuals fought in groups such as Abu Musab lowing the 2003 U.S. -

War Economy in Syria Study

War Economy in Syria Study 1 War Economy in Syria Study 1 War Economy in Syria Study .................................................................................................................. ............................ .......... ......................................... ............................ .................................................................................................................... ........................................ ................................................................................................................................... .................................................................................................... ........................................................................................................... ........................................................................................................ ....... ............................................................................................................. .................................................. .................................................................................................... .......................................................................................... ...................... ...................................................................... .............................................................................................. ..................................................................................................... -

SYRIAN ARAB REPUBLIC North East Syria Displacement 28 October 2019

SYRIAN ARAB REPUBLIC North East Syria displacement 28 October 2019 OVERVIEW 105,574 The onset of military operations in Northeast Syria by the Turkish army and allied non-state groups on 9 October has forced huge People currently displaced numbers of people to flee their homes. Around 105,574 remain displaced as of 28 October, and an additional 96,855 people were displaced and have since returned. Of those currently displaced, 98,798 are from Al Hassakeh and Ar Raqqa, and 6,776 are from 96,855 Aleppo. Displaced people are finding shelter with friends and family and also in informal settlements and collective shelters. People reported to have returned There are 69 such shelters in Al Hasakeh Governorate alone. Over 12,200 people have reportedly been displaced into neighboring Iraq. Prior to 9 October, Northeast Syria already hosted a total of 710,000 people displaced from earlier phases of the conflict, around 91,000 of whom remain in Al Hol, Areesha, Mahmoudi, Newroz and Roj camps. North East Syria Newroz Roj Jawadiyah 4 ] ] 5 1,808 Qahtaniyyeh TURKEY Darbasiyah Amuda Ain al Arab Jarablus Tell Ras Al Ain Abiad 2 To Iraq Mabroka * Menbij Al-Hasakeh Tal Hmis 12,238 Suluk 2 Ein Issa Tal Tamer Ar-Raqqa 51 Areesha Al-Hol Legend To Aleppo Camp AlKalta Alzahira Tal Alsamn Janoby Almazuneh Abu 8,475 68,577 IDP collective shelters / No. Hatash Jurneyyeh Abu Kubry Royan Khashab Informal IDP settlments Alajaj Jarwah Alrasheed Tawaiheneh Alasdyah-Alfqubour Road (M4) AlGhaba Al Fateh Rabeah Mazraat Yareb Tal AlBayah Al-Hasakeh Lake/river Mahmoudli AlSalhabeh AlKhatonyeh Population movement Alqarbia Abu Kubea 7,321 Alhamam 6,290 Empty Camp Henedeh Ath-Thawra Displaced TO Deir-ez-Zor 35k Sur 600 74k The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. -

Syria Drought Response Plan

SYRIA DROUGHT RESPONSE PLAN A Syrian farmer shows a photo of his tomato-producing field before the drought (June 2009) (Photo Paolo Scaliaroma, WFP / Surendra Beniwal, FAO) UNITED NATIONS SYRIAN ARAB REPUBLIC - Reference Map Elbistan Silvan Siirt Diyarbakir Batman Adiyaman Sivarek Kahramanmaras Kozan Kadirli TURKEY Viransehir Mardin Sanliurfa Kiziltepe Nusaybin Dayrik Zakhu Osmaniye Ceyhan Gaziantep Adana Al Qamishli Nizip Tarsus Dortyol Midan Ikbis Yahacik Kilis Tall Tamir AL HASAKAH Iskenderun A'zaz Manbij Saluq Afrin Mare Al Hasakah Tall 'Afar Reyhanli Aleppo Al Bab Sinjar Antioch Dayr Hafir Buhayrat AR RAQQA As Safirah al Asad Idlib Ar Raqqah Ash Shaddadah ALEPPO Hamrat Ariha r bu AAbubu a add D Duhuruhur Madinat a LATAKIA IDLIB Ath Thawrah h Resafa K l Ma'arat a Haffe r Ann Nu'man h Latakia a Jableh Dayr az Zawr N El Aatabe Baniyas Hama HAMA Busayrah a e S As Saiamiyah TARTU S Masyaf n DAYR AZ ZAWR a e n Ta rtus Safita a Dablan r r e Tall Kalakh t Homs i Al Hamidiyah d Tadmur E e uphrates Anah M (Palmyra) Tripoli Al Qusayr Abu Kamal Sadad Al Qa’im HOMS LEBANON Al Qaryatayn Hadithah BEYRUT An Nabk Duma Dumayr DAMASCUS Tyre DAMASCUS QQuneitrauneitra Ar Rutbah QUNEITRA Haifa Tiberias AS SUWAIDA IRAQ DAR’A Trebil ISRAELI S R A E L DDarar'a As Suwayda Irbid Jenin Mahattat al Jufur Jarash Nabulus Al Mafraq West JORDAN Bank AMMAN JERUSALEM Bayt Lahm Madaba SAUDI ARABIA Legend Elevation (meters) National capital 5,000 and above First administrative level capital 4,000 - 5,000 Populated place 3,000 - 4,000 International boundary 2,500 - 3,000 First administrative level boundary 2,000 - 2,500 1,500 - 2,000 050100150 1,000 - 1,500 800 - 1,000 km 600 - 800 Disclaimers: The designations employed and the presentation of material 400 - 600 on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal 200 - 400 status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

![[FSL] Insights on Northwest Syria - Issue 11 188//21, 10:36 AM](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9034/fsl-insights-on-northwest-syria-issue-11-188-21-10-36-am-849034.webp)

[FSL] Insights on Northwest Syria - Issue 11 188//21, 10:36 AM

[FSL] Insights on Northwest Syria - Issue 11 188//21, 10:36 AM Subscribe Past Issues Translate View this email in your browser Issue 11 18 August 2021 Insights on Northwest Syria Monthly Updates from FSL Cluster The re-assessment in NW Syria to review the number of acute food insecure people has been completed in NW Syria and integrated into the "FSL gap analysis" database (traffic lights). The re-assessment has provided the following results: The population figure has been updated by OCHA as of May 2021; an estimated number of 4,627,721 people currently live in NW Syria in the areas accessible by the FSL partners. 87,228 persons are acute food insecure as a result of the re-assessment, reaching the total number of 3.4M people in need in NW Syria. The reassessment was conducted in May 2021 in 13 sub-districts (Atareb, Afrin, Al Bab, Jandairis, Jarablus, Salqin, Sharan, Bennsh, Ariha, Mhambal, Ehsem, Mare, and Badama). The mid-year review (MYR) will be published in September 2021 by Whole of Syria. MAY 2021 - Key Achievements of the FSL Cluster Partners https://mailchi.mp/fscluster/insights-on-northwest-syria-issue-11?e=0301ef5d6e Page 1 of 5 [FSL] Insights on Northwest Syria - Issue 11 188//21, 10:36 AM 53 partners implemented SO1, SO2 and SO3 activities in northwest Syria (NWS) in May 2021. In May 2021, FSL partners delivered food assistance to the People in Need (PIN), according to the following percentage of beneficiaries reached out in 40 sub-districts in NWS: 9 sub-districts reached above 100% PIN, 5 sub-districts from 100% to 76% PIN, 10 sub-districts from 75% to 51% PIN, 3 sub-districts from 50% to 26% PIN, and 13 sub-districts were covered by less than 25% PIN. -

Assyrians Under Kurdish Rule: The

Assyrians Under Kurdish Rule e Situation in Northeastern Syria Assyrians Under Kurdish Rule The Situation in Northeastern Syria Silvia Ulloa Assyrian Confederation of Europe January 2017 www.assyrianconfederation.com [email protected] The Assyrian Confederation of Europe (ACE) represents the Assyrian European community and is made up of Assyrian national federations in European countries. The objective of ACE is to promote Assyrian culture and interests in Europe and to be a voice for deprived Assyrians in historical Assyria. The organization has its headquarters in Brussels, Belgium. Cover photo: Press TV Contents Introduction 4 Double Burdens 6 Threats to Property and Private Ownership 7 Occupation of facilities Kurdification attempts with school system reform Forced payments for reconstruction of Turkish cities Intimidation and Violent Reprisals for Self-Determination 9 Assassination of David Jendo Wusta gunfight Arrest of Assyrian Priest Kidnapping of GPF Fighters Attacks against Assyrians Violent Incidents 11 Bombings Provocations Amuda case ‘Divide and Rule’ Strategy: Parallel Organizations 13 Sources 16 4 Introduction Syria’s disintegration as a result of the Syrian rights organizations. Among them is Amnesty Civil War created the conditions for the rise of International, whose October 2015 publica- Kurdish autonomy in northern Syria, specifi- tion outlines destructive campaigns against the cally in the governorates of Al-Hasakah and Arab population living in the region. Aleppo. This region, known by Kurds as ‘Ro- Assyrians have experienced similar abuses. java’ (‘West’, in West Kurdistan), came under This ethnic group resides mainly in Al-Ha- the control of the Kurdish socialist Democratic sakah governorate (‘Jazire‘ canton under the Union Party (abbreviated PYD) in 2012, after PYD, known by Assyrians as Gozarto). -

Download the Full Report

HUMAN “Maybe We Live RIGHTS and Maybe We Die” WATCH Recruitment and Use of Children by Armed Groups in Syria “Maybe We Live and Maybe We Die” Recruitment and Use of Children by Armed Groups in Syria Copyright © 2014 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-1425 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org JUNE 2014 ISBN: 978-1-62313-1425 “Maybe We Live and Maybe We Die” Recruitment and Use of Children by Armed Groups in Syria Summary ......................................................................................................................... 1 Recommendations ........................................................................................................... 5 To All Armed Groups Fighting in Syria ....................................................................................... -

Governing Rojava Layers of Legitimacy in Syria Contents

Research Paper Rana Khalaf Middle East and North Africa Programme | December 2016 Governing Rojava Layers of Legitimacy in Syria Contents Summary 2 Acronyms and Overview of Key Listed Actors 3 Introduction 5 PYD Pragmatism and the Emergence of ‘Rojava’ 8 Smoke and Mirrors: The PYD’s Search for Legitimacy Through Governance 10 1. Provision of security 12 2. Effectiveness in the provision of services 16 3. Diplomacy and image management 21 Conclusion: The Importance of Local Trust and Representation 24 About the Author 26 Acknowledgments 27 1 | Chatham House Governing Rojava: Layers of Legitimacy in Syria Summary • Syria is without functioning government in many areas but not without governance. In the northeast, the Democratic Union Party (PYD) has announced its intent to establish the federal region of Rojava. The PYD took control of the region following the Syrian regime’s handover in some Kurdish-majority areas and as a consequence of its retreat from others. In doing so, the PYD has displayed pragmatism and strategic clarity, and has benefited from the experience and institutional development of its affiliate organization, the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK). The PYD now seeks to further consolidate its power and to legitimize itself through the provision of security, services and public diplomacy; yet its local legitimacy remains contested. • The provision of security is paramount to the PYD’s quest for legitimacy. Its People’s Defense Units (YPG/YPJ) have been an effective force against the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), winning the support of the local population, particularly those closest to the front lines. -

SYRIA - IDLEB Humanitarian Purposes Only IDP Location - As of 23 Oct 2015 Production Date : 26 Oct 2015

SYRIA - IDLEB Humanitarian Purposes Only IDP Location - As of 23 Oct 2015 Production date : 26 Oct 2015 Nabul Al Bab MARE' JANDAIRIS AFRIN NABUL Tadaf AL BAB Atma ! Qah ² ! Daret Haritan Azza TADAF Reyhanli DARET AZZA HARITAN DANA Deir Hassan RASM HARAM !- Darhashan Harim Jebel EL-IMAM Tlul Dana ! QOURQEENA Saman Antakya Ein Kafr Hum Elbikara Big Hir ! ! Kafr Mu Jamus ! Ta l ! HARIM Elkaramej Sahara JEBEL SAMAN Besnaya - Sarmada ! ! Bseineh Kafr ! Eastern SALQIN ! Qalb Ariba Deryan Kafr ! Htan ! Lozeh ! Kafr Naha Kwaires ! Barisha Maaret ! ! Karmin TURKEY Allani ! Atarib ! Kafr Rabeeta ! Radwa ! Eskat ! ! Kila ! Qourqeena Kafr Naseh Atareb Elatareb Salqin Kafr ! EASTERN KWAIRES Delbiya Meraf ! Kafr Elshalaf Takharim Mars ! Kafr ! Jeineh Aruq ! Ta lt i t a ! Hamziyeh ! Kelly ! Abu ! Ta lh a ATAREB ! Kaftin Qarras KAFR TAKHARIMHelleh ! Abin ! Kafr ! Hazano ! Samaan Hind ! Kafr ! Kuku - Thoran Ein Eljaj ! As Safira Armanaz ! Haranbush ! Maaret Saidiyeh Kafr Zarbah ! Elekhwan Kafr - Kafr ! Aleppo Kafrehmul ! Azmarin Nabi ! Qanater Te ll e m ar ! ! ! ! Dweila Zardana AS-SAFIRA ! Mashehad Maaret Elnaasan ! Biret MAARET TAMSRIN - Maaret Ramadiyeh Elhaski Ghazala -! Armanaz ! ! Mgheidleh Maaret ! ARMANAZKuwaro - Shallakh Hafasraja ! Um Elriyah ! ! Tamsrin TEFTNAZ ! Zanbaqi ! Batenta ! ALEPPO Milis ! Kafraya Zahraa - Maar Dorriyeh Kherbet ! Ta m sa ri n Teftnaz Hadher Amud ! ! Darkosh Kabta Quneitra Kafr Jamiliya ! ! ! Jales Andnaniyeh Baliya Sheikh ! BENNSH Banan ! HADHER - Farjein Amud Thahr Yousef ! ! ! ! Ta lh i ye h ZARBAH Nasra DARKOSH Arshani -

Syria - Displacements from Northern Syria Production Date : 25/08/2016 IDP Locations - As of 16 August 2016

For Humanitarian Purposes Only Syria - Displacements from Northern Syria Production date : 25/08/2016 IDP Locations - As of 16 August 2016 Total number of IDPs: 749,275 BULBUL Raju " RAJU Shamarin Talil Elsham ² Krum Zayzafun - Ekdeh Gender & Age SHARAN Shmarekh Sharan Kafrshush Baraghideh " Tatiyeh Jdideh Maarin Ar-Ra'ee Salama AR-RA'EE " Nayara Ferziyeh A'ZAZ Azaz " Azaz Niddeh 19% MA'BTALI Sijraz Yahmul Maabatli Suran " Jarez " Kafr Kalbein 31% Maraanaz Girls under 18 Al-Malikeyyeh Kaljibrin AGHTRIN Afrin Manaq Akhtrein Boys under 18 " " Sheikh El-Hadid " Mare' Women " A'RIMA Tall Refaat 24% " Men Baselhaya TALL REFAAT AFRIN Deir Jmal MARE' Kafr Naseh Tal Refaat 26% Kafrnaya JANDAIRIS Jandairis " Nabul AL BAB " Al Bab " NABUL Tal Jbine Tadaf " Shelter Type Hayyan T U R K E Y Qah Atma Selwa Random gatherings HARITAN Andan Haritan TADAF Unfinished houses or Daret Azza " " buildings Reyhanli Kafr Bssin Other Qabtan Eljabal Tilaada Individual tents DARET AZZA A L E P P O Babis Deir Hassan - Darhashan Hur Maaret Elartiq Kafr Hamra Rented houses DANA Hezreh - Hezri Termanin Dana Anjara Foziyeh Harim " Bshantara RASM HARAM EL-IMAM Open areas " Tqad Majbineh Aleppo Antakya Ras Elhisn " Total Tlul Kafr Hum Ein Elbikara Aleppo HARIM Tuwama Hoteh Under trees Kafr Mu Tlul Big Hir Jamus QOURQEENA Tal Elkaramej Sahara JEBEL SAMAN Um Elamad Alsafira Besnaya - Bseineh Sarmada Oweijel Htan Tadil Collective center Ariba Qalb Lozeh Barisha Eastern Kwaires " Bozanti Kafr Deryan Kafr Karmin Abzemo Maaret Atarib Allani Radwa Kafr Taal Kafr Naha Home Kafr -

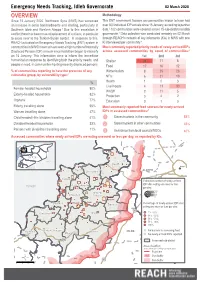

Emergency Needs Tracking, Idleb Governorate

Emergency Needs Tracking, Idleb Governorate 02 March 2020 OVERVIEW Methodology Since 15 January 2020, Northwest Syria (NWS) has witnessed This ENT assessment focuses on communities known to have had an increase in aerial bombardments and shelling, particularly in over 300 individual IDP arrivals since 15 January, according to partner Southern Idleb and Western Aleppo.1 Due to this escalation in data.2 102 communities were covered across 15 sub-districts in Idleb conflict there has been mass displacement of civilians, in particular governorate.3 Data collection was conducted remotely on 02 March to areas near to the Turkish-Syrian border. In response to this, through REACH’s network of key informants (KIs) in NWS with one REACH activated an Emergency Needs Tracking (ENT) system in KI interviewed per community.4 communities in NWS known to have seen a high number of Internally Most commonly reported priority needs of newly-arrived IDPs Displaced Person (IDP) arrivals since hostilities began to intensify across assessed communities by count of communities:+ on 15 January. This information aims to inform the immediate 1st 2nd 3rd humanitarian response by identifying both the priority needs, and Shelter 64 11 8 people in need, in communities hosting recently displaced persons. Food 17 16 12 % of communities reporting to have the presence of any Winterisation 8 25 23 vulnerable group, by vulnerability type:* NFIs 6 21 19 % Health 1 0 3 Livelihoods 4 13 30 Female-headed households 90% WASH 2 11 5 Elderly-headed households 82% Protection 0 4 2