Does Assam's Nrc Theaten India's Secularity?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Numbers in Bengali Language

NUMBERS IN BENGALI LANGUAGE A dissertation submitted to Assam University, Silchar in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Masters of Arts in Department of Linguistics. Roll - 011818 No - 2083100012 Registration No 03-120032252 DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS SCHOOL OF LANGUAGE ASSAM UNIVERSITY SILCHAR 788011, INDIA YEAR OF SUBMISSION : 2020 CONTENTS Title Page no. Certificate 1 Declaration by the candidate 2 Acknowledgement 3 Chapter 1: INTRODUCTION 1.1.0 A rapid sketch on Assam 4 1.2.0 Etymology of “Assam” 4 Geographical Location 4-5 State symbols 5 Bengali language and scripts 5-6 Religion 6-9 Culture 9 Festival 9 Food havits 10 Dresses and Ornaments 10-12 Music and Instruments 12-14 Chapter 2: REVIEW OF LITERATURE 15-16 Chapter 3: OBJECTIVES AND METHODOLOGY Objectives 16 Methodology and Sources of Data 16 Chapter 4: NUMBERS 18-20 Chapter 5: CONCLUSION 21 BIBLIOGRAPHY 22 CERTIFICATE DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS SCHOOL OF LANGUAGES ASSAM UNIVERSITY SILCHAR DATE: 15-05-2020 Certified that the dissertation/project entitled “Numbers in Bengali Language” submitted by Roll - 011818 No - 2083100012 Registration No 03-120032252 of 2018-2019 for Master degree in Linguistics in Assam University, Silchar. It is further certified that the candidate has complied with all the formalities as per the requirements of Assam University . I recommend that the dissertation may be placed before examiners for consideration of award of the degree of this university. 5.10.2020 (Asst. Professor Paramita Purkait) Name & Signature of the Supervisor Department of Linguistics Assam University, Silchar 1 DECLARATION I hereby Roll - 011818 No - 2083100012 Registration No – 03-120032252 hereby declare that the subject matter of the dissertation entitled ‘Numbers in Bengali language’ is the record of the work done by me. -

Guwahati Development

Editorial Board Advisers: Hrishikesh Goswami, Media Adviser to the Chief Minister, Assam V.K. Pipersenia, IAS, Chief Secretary, Assam Members: L.S. Changsan, IAS, Principal Secretary to the Government of Assam, Home & Political, I&PR, etc. Rajib Prakash Baruah, ACS, Additional Secretary to the Government of Assam, I&PR, etc. Ranjit Gogoi, Director, Information and Public Relations Pranjit Hazarika, Deputy Director, Information and Public Relations Manijyoti Baruah, Sr. Planning and Research Officer, Transformation & Development Department Z.A. Tapadar, Liaison Officer, Directorate of Information and Public Relations Neena Baruah, District Information and Public Relations Officer, Golaghat Antara P.P. Bhattacharjee, PRO, Industries & Commerce Syeda Hasnahana, Liaison Officer, Directorate of Information and Public Relations Photographs: DIPR Assam, UB Photos First Published in Assam, India in 2017 by Government of Assam © Department of Information and Public Relations and Department of Transformation & Development, Government of Assam. All Rights Reserved. Design: Exclusive Advertising Pvt. Ltd., Guwahati Printed at: Assam Government Press 4 First year in service to the people: Dedicated for a vibrant, progressive and resurgent Assam In a democracy, the people's mandate is supreme. A year ago when the people of Assam reposed their faith in us, we were fully conscious of the responsibility placed on us. We acknowledged that our actions must stand up to the people’s expectations and our promise to steer the state to greater heights. Since the formation of the new State Government, we have been striving to bring positive changes in the state's economy and social landscape. Now, on the completion of a year, it makes me feel satisfied that Assam is on a resurgent growth track on all fronts. -

The Spectre of SARS-Cov-2 in the Ambient Urban Natural Water in Ahmedabad and Guwahati: a Tale of Two Cities

medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.06.12.21258829; this version posted June 16, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under a CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license . The Spectre of SARS-CoV-2 in the Ambient Urban Natural Water in Ahmedabad and Guwahati: A Tale of Two Cities Manish Kumar1,2*, Payal Mazumder3, Jyoti Prakash Deka4, Vaibhav Srivastava1, Chandan Mahanta5, Ritusmita Goswami6, Shilangi Gupta7, Madhvi Joshi7, AL. Ramanathan8 1Discipline of Earth Science, Indian Institute of Technology Gandhinagar, Gujarat 382 355, India 2Kiran C Patel Centre for Sustainable Development, Indian Institute of Technology Gandhinagar, Gujarat, India 3Centre for the Environment, Indian Institute of Technology Guwahati, Assam 781039, India 4Discipline of Environmental Sciences, Gauhati Commerce College, Guwahati, Assam 781021, India 5Department of Civil Engineering, Indian Institute of Technology Guwahati, Assam 781039, India 6Tata Institute of Social Science, Guwahati, Assam 781012, India 7Gujarat Biotechnology Research Centre (GBRC), Sector- 11, Gandhinagar, Gujarat 382 011, India 8School of Environmental Sciences, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi 110067, India *Corresponding Author: [email protected]; [email protected] Manish Kumar | Ph.D, FRSC, JSPS, WARI+91 863-814-7602 | Discipline of Earth Science | IIT Gandhinagar | India 1 NOTE: This preprint reports new research that has not been certified by peer review and should not be used to guide clinical practice. medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.06.12.21258829; this version posted June 16, 2021. -

Director's Report

DIRECTOR'S REPORT First Convocation 19th M ay, 1999. Hon ' ble Govern or of Assam and Chairman of the Board of Governors of liT Guwahati, Gen. S.K. Sin ha, Hon' ble Chi ef Minister of Assam, Shri Prafu ll a Kumar Mahanta, Members of the Board of Governors, Members of the Senate, grad uating students, ladies and gentlemen: It gives me great pleasure to extend a very warm welcome to all of you on the occasion of the very first convocation of the Ind ian Institute of Technology, Guwahati. It is our privil ege on this hi storic occasio n to have amidst us the Hon' ble Chief Minister of Assam, Shri Mahanta, who, as the then President of the All Assam Students' Un ion in 1985, was one of the architects of the Assam Accord and was instrumental in paving the way for settin g up of a sixth liT in Assam as a part of that Accord. We therefore extend a very special welc ome to you, Sir, and look forward to hearing yo ur Convocation address. It is my pleasant duty now to present to you a rep0\1 of the acti vities of thi s Institute fro m the time of its establ ishment till now. I would like to begin the report with the genesis of th is Institute. GENESIS The Assam Accord signed in August 1985 by the then Prime Mi nister, Sri Raji v Gandh i, and the student leaders of the A ll Assam Students Unio n, stipulated among other clauses, that an IlT be set up in the State of Assam. -

International Journal of Global Economic Light (JGEL) Journal DOI

SJIF Impact Factor: 6.047 Volume: 6 | November - October 2019 -2020 ISSN(Print ): 2250 – 2017 International Journal of Global Economic Light (JGEL) Journal DOI : https://doi.org/10.36713/epra0003 IDENTITY MOVEMENTS AND INTERNAL DISPLACEMENT IN ASSAM Ananda Chandra Ghosh Assistant Professor, Department of Political Science, Cachar College, Silchar,788001,Assam, India ABSTRACT Assam, the most populous state of North East India has been experiencing the problem of internal displacement since independence. The environmental factors like the great earth quake of 1950 displaced many people in the state. Flood and river bank erosion too have caused displacement of many people in Assam every year. But the displacement which has drawn the attention of the social scientists is the internal displacement caused by conflicts and identity movements. The Official Language Movement of 1960 , Language movement of 1972 and the Assam movement(1979-1985) were the main identity movements which generated large scale violence conflicts and internal displacement in post colonial Assam .These identity movements and their consequence internal displacement can not be understood in isolation from the ethno –linguistic composition, colonial policy of administration, complex history of migration and the partition of the state in 1947.Considering these factors in the present study an attempt has been made to analyze the internal displacement caused by Language movements and Assam movement. KEYWORDS: displacement, conflicts, identity movements, linguistic composition DISCUSSION are concentrated in the different corners of the state. Some of The state of Assam is considered as mini India. It is these Tribes have assimilated themselves and have become connected with main land of India with a narrow patch of the part and parcel of Assamese nationality. -

English Speech 2020 (Today).Pmd

1. Speaker Sir, I stand before this August House today to present my fifth and final budget as Finance Minister of this Government led by Hon’ble Chief Minister Shri Sarbananda Sonowal. With the presentation of this Budget, I am joining the illustrious list of all such full-time Finance Ministers who had the good fortune of presenting five budgets continuously. From the Financial Year 1952-53 up to 1956-57, Shri Motiram Bora, from 1959-60 to 1965-66, former president of India Shri Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed in his capacity as Finance Minister of Assam, and then Shri Kamakhya Prasad Tripathi from 1967-68 to 1971-72 presented budgets for five or more consecutive years before this August House. Of course, as and when the Chief Ministers have held additional responsibility as Finance Minister, they have presented the budget continuously for five or more years. This achievement has been made possible only because of the faith reposed in me by the Hon’ble Chief Minister, Shri Sarbananda Sonowal and by the people of Assam. I also thank the Almighty for bestowing upon me this great privilege. This also gives us an opportune moment to now digitise all the budget speeches presented before this August House starting from the first budget laid by Maulavi Saiyd Sir Muhammad Saadulla on 3rd August 1937. 2. Hon’ble Speaker Sir, on May 24, 2016, a new era dawned in Assam; an era of hope, of aspiration, of development and of a promise of a future that embraces everyone. Today, I stand before you in all humility, to proudly state that we have done our utmost to keep that promise. -

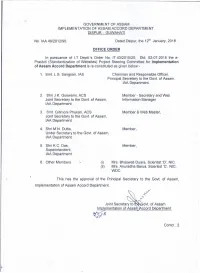

Government of Assam Implementation of Assam Accord Department

GOVERNMENT OF ASSAM IMPLEMENTATION OF ASSAM ACCORD DEPARTMENT. DISPUR :: GUWAHATI No. IAA 49/2012/90, Dated Dsipur, the 1ih January, 2018 . OFFICE ORDER In pursuance of LT DepU.'s Order No. IT.43/2015/20, Dtd. 02-07-2015 the e- Prastuti (Standardization of Websites) Project Steering Committee for Implementation of-Assam Accord Department is re-constituted as given below:- 1. Smt. L.S. Sangsan, IAS Chairman and Responsible Officer, Principal Secretary to the Govt. of Assam, IAA Department. 2. Shri J.K. Goswami, ACS Member - Secretary and Web Joint Secretary to the Govt. of Assam, Information Manager IAA Department. 3. Smt. Gitimoni Phukan, ACS Member & Web Master, Joint Secretary to the Govt. of Assam, IAA Department. 4. Shri M.N. DuUa, Member, Under Secretary to the Govt. of Assam, IAA Department. 5. Shri K.C. Das, Member, Superintendent, IAA Department. 6. Other Members (i) Mrs. Bhaswati Duara, Scientist '0', NIC. (ii) Mrs. Anuradha Barua, Scientist 'C', NIC. WDC. This has the approval of the Principal Secretary to the Govt. of Assam, Implementation of Assam Accord Department. Joint Secretary to t Im lementation of Assa Contd ... 2 -2- Memo No. IAA 49/2012/ 90-A Dated Dsipur, the 12th January,2018. Copy to: 1. P.S. to the Additional Chief Secretary to the Govt. of Assam, Information Technology Department, Dispur for kind appraisal of the Additional Chief Secretary. 2. P.S. to the Principal Secretary to the Govt. of Assam, Implementation of Assam Accord Department, Dispur for kind appraisal of the Principal Secretary. 3. The Commissioner & Secretary to the Govt. -

Contribution of Gauripur Zamindar Raja Prabhat Chandra Barua: - a Historical Analysis

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 19, Issue 1, Ver. V (Jan. 2014), PP 56-60 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org Contribution of Gauripur zamindar Raja Prabhat Chandra Barua: - A historical analysis Rabindra Das Assistant Professor, Department of History,Bholanath College, Dhubri, India Abstract: The zamindary of Gauripur situated in the district of Goalpara (undivided), now present district of Dhubri. Gauripur zamindary is larger in size than any other zamindary in Goalpara. The size of zamindary was 355 square miles. It was originated from the Nankar receipt from Mughal Emperor Jahangir. Kabindra Patra was appointed to the post of Naib kanangu of the thana Rangamati, situated near Gauripur. His descendants had enjoyed the office of Kananguship for more than 300 years. The zamindars of Gauripur are mainly feudal in nature. Their main motive was to occupy land and possessed a vast tract of land in the 2nd decade of 17th century. The zamindars of Gauripur were conservative in their outlook but some of the zamindars of Gauripur paid their attention to benevolent public works. Once a time western Assam was more advance than eastern Assam because of the benevolent activities of Gauripur zamindars. Raja Prabhat Chandra Barua was one of the zamindars in Gauripur zamindary who paid attention to develop the society in every sphere. He was an exchequer in the public works, viz. education 52%, hospital 16%, sadabrata 18%, donation 12%, and public health 2%. Thus he contributed in every aspect of society, education, art, culture, economic, and so on for the welfare of the mass people. -

Cabinet Approves High Level Committee to Implement Clause 6 of Assam Accord Several Longstanding Demands of Bodos Also Approved

Cabinet approves high level committee to implement Clause 6 of Assam Accord Several Longstanding demands of Bodos also approved Posted On: 02 JAN 2019 5:58PM by PIB Delhi The Union Cabinet chaired by Prime Minister Shri Narendra Modi today approved the setting up of a High Level Committee for implementation of Clause 6 of the Assam Accord and measures envisaged in the Memorandum of Settlement, 2003 and other issues related to Bodo community. After Assam agitation of 1979-1985, Assam Accord was signed on 15th August, 1985. Clause 6 of the Assam Accord envisaged that appropriate constitutional, legislative and administrative safeguards, shall be provided to protect, preserve and promote the cultural, social, linguistic identity and heritage of the Assamese people. However, it has been felt that Clause 6 of the Assam Accord has not been fully implemented even almost 35 years after the Accord was signed. The Cabinet, therefore, approved the setting up of a High Level Committee to suggest constitutional, legislative and administrative safeguards as envisaged in Clause 6 of the Assam Accord. The Committee shall examine the effectiveness of actions since 1985 to implement Clause 6 of the Assam Accord. The Committee will hold discussions with all stakeholders and assess the required quantum of reservation of seats in Assam Legislative Assembly and local bodies for Assamese people. The Committee will also assess the requirement of measures to be taken to protect Assamese and other indigenous languages of Assam, quantum of reservation in employment under Government of Assam and other measures to protect, preserve and promote cultural, social, linguistic identity and heritage of Assamese people. -

Empire's Garden: Assam and the Making of India

A book in the series Radical Perspectives a radical history review book series Series editors: Daniel J. Walkowitz, New York University Barbara Weinstein, New York University History, as radical historians have long observed, cannot be severed from authorial subjectivity, indeed from politics. Political concerns animate the questions we ask, the subjects on which we write. For over thirty years the Radical History Review has led in nurturing and advancing politically engaged historical research. Radical Perspec- tives seeks to further the journal’s mission: any author wishing to be in the series makes a self-conscious decision to associate her or his work with a radical perspective. To be sure, many of us are currently struggling with the issue of what it means to be a radical historian in the early twenty-first century, and this series is intended to provide some signposts for what we would judge to be radical history. It will o√er innovative ways of telling stories from multiple perspectives; comparative, transnational, and global histories that transcend con- ventional boundaries of region and nation; works that elaborate on the implications of the postcolonial move to ‘‘provincialize Eu- rope’’; studies of the public in and of the past, including those that consider the commodification of the past; histories that explore the intersection of identities such as gender, race, class and sexuality with an eye to their political implications and complications. Above all, this book series seeks to create an important intellectual space and discursive community to explore the very issue of what con- stitutes radical history. Within this context, some of the books pub- lished in the series may privilege alternative and oppositional politi- cal cultures, but all will be concerned with the way power is con- stituted, contested, used, and abused. -

History of North East India (1228 to 1947)

HISTORY OF NORTH EAST INDIA (1228 TO 1947) BA [History] First Year RAJIV GANDHI UNIVERSITY Arunachal Pradesh, INDIA - 791 112 BOARD OF STUDIES 1. Dr. A R Parhi, Head Chairman Department of English Rajiv Gandhi University 2. ************* Member 3. **************** Member 4. Dr. Ashan Riddi, Director, IDE Member Secretary Copyright © Reserved, 2016 All rights reserved. No part of this publication which is material protected by this copyright notice may be reproduced or transmitted or utilized or stored in any form or by any means now known or hereinafter invented, electronic, digital or mechanical, including photocopying, scanning, recording or by any information storage or retrieval system, without prior written permission from the Publisher. “Information contained in this book has been published by Vikas Publishing House Pvt. Ltd. and has been obtained by its Authors from sources believed to be reliable and are correct to the best of their knowledge. However, IDE—Rajiv Gandhi University, the publishers and its Authors shall be in no event be liable for any errors, omissions or damages arising out of use of this information and specifically disclaim any implied warranties or merchantability or fitness for any particular use” Vikas® is the registered trademark of Vikas® Publishing House Pvt. Ltd. VIKAS® PUBLISHING HOUSE PVT LTD E-28, Sector-8, Noida - 201301 (UP) Phone: 0120-4078900 Fax: 0120-4078999 Regd. Office: 7361, Ravindra Mansion, Ram Nagar, New Delhi – 110 055 Website: www.vikaspublishing.com Email: [email protected] About the University Rajiv Gandhi University (formerly Arunachal University) is a premier institution for higher education in the state of Arunachal Pradesh and has completed twenty-five years of its existence. -

Assam Development Report

The Core Committee (Composition as in 2002) Dr. K. Venkatasubramanian Member, Planning Commission Chairman Shri S.C. Das Commissioner (P&D), Government of Assam Member Prof Kirit S. Parikh Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research Member Dr. Rajan Katoch Adviser (SP-NE), Planning Commission Member-Convener Ms. Somi Tandon for the Planning Commission and Shri H.S. Das & Dr. Surojit Mitra from the Government of Assam served as members of the Core Committee for various periods during 2000-2002. Project Team Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research, Mumbai Professor Kirit S. Parikh (Leader and Editor) Professor P. V. Srinivasan Professor Shikha Jha Professor Manoj Panda Dr. A. Ganesh Kumar Centre for North East Studies and Policy Research, New Delhi Shri Sanjoy Hazarika Shri Biswajeet Saikia Omeo Kumar Das Institute of Social Change and Development, Guwahati Dr. B. Sarmah Dr. Kalyan Das Professor Abu Nasar Saied Ahmed Indian Statistical Institute, New Delhi Professor Atul Sarma Acknowledgements We thank Planning Commission and the Government of Assam for entrusting the task to prepare this report to Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research (IGIDR). We are particularly indebted to Dr. K. Venkatasubramanian, Member, Planning Commission and Chairman of the Core Committee overseeing the preparation of the Report for his personal interest in this project and encouragement and many constructive suggestions. We are extremely grateful to Dr. Raj an Katoch of the Planning Commission for his useful advice, overall guidance and active coordination of the project, which has enabled us to bring this exercise to fruition. We also thank Ms. Somi Tandon, who helped initiate the preparation of the Report, all the members of the Core Committee and officers of the State Plans Division of the Planning Commission for their support from time to time.