National College Physical Education Association For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2012 Opponents PACIFIC UNIVERSITY FOOTBALL PACIFIC Football 50 •Pacific University 2012 Opponents Forest Grove,Ore

Quick Facts/Contents 2012 Pacific Football Quick Facts Contents PACIFIC UNIVERSITY FOOTBALL COACHING STAFF GENERAL INFORMATION 2-4 Location: Forest Grove, Ore. Head Coach: Keith Buckley Quick Facts.............................................................................3 Founded: 1849 Alma Mater: UC Davis (1996) 2012 Schedule..........................................3 & Back Cover Media Information...............................................................4 National Affiliation: NCAA Division III Record At Pacific/Years: 1-18/2 Years Broadcast Information....................................................4 Conference: Northwest Conference Overall Record/Years: 1-18/12 Years Enrollment: 3,302 (1,603 undergraduate) Offensive Coordinator: Jim Craft (3rd Season) 2012 SEASON PREVIEW 6-8 Colors: Red (PMS 1805), Black & White Defensive Coordinator/ Nickname: Boxers Recruiting Coordinator: Jacob Yoro (3rd Season) COACHING STAFF 9-14 President: Dr. Lesley Hallick Offensive Line Coach/ Head Coach Keith Buckley...........................................10 Director of Athletics: Ken Schumann Strength & Conditioning: Ian Falconer (3rd Season) Football Staff.......................................................................11 Associate Athletic Director: Lauren Esbensen Running Backs Coach: Mike McCabe (3rd Season) 2012 PLAYERS 15-48 Sports Information Director: Blake Timm Kickers Coach: Jason Daily (3rd Season) Roster.....................................................................16 Head Athletic Trainer: Linda McIntosh Offensive -

Changing the Game

TERRIER PRIDE Boston University Athletics Development & Alumni Relations CHANGING THE GAME 595 Commonwealth Avenue, Suite 700 The Campaign for Athletics at Boston University West Entrance Boston, Massachusetts 02215 617-353-3008 [email protected] goterriers.com/changingthegame TO THE FRIENDS OF BU ATHLETICS: In the nearly century-long history of Boston University Athletics, there have been many extraordinary accomplishments and sensational moments, including five national championships in men’s hockey, two national championship games for women’s hockey (a mere eight years after the varsity program was founded), and seven appearances in the NCAA men’s basketball tourney, including a trip to the Elite Eight. Boston University has produced scores of Olympians, a member of baseball’s Hall of Fame, several NBA players, and over 60 members of the NHL—more than any other American university. In recent years, our programs have dominated their conferences. Boston University captured the America East Conference Commissioner’s Cup, awarded to the school with the strongest athletic program, seven years in a row and ten times in the last eleven years. But just as important as these athletic accomplishments are the achievements of our students in the classroom and the community. In the past three years, they have put in more than 10,000 hours of community service. The graduation rate for BU student-athletes is 95 percent, and their cumulative grade point average is over 3.1. In 2012, we set a new record, with ten student-athletes receiving the prestigious Scarlet Key honor—the University’s highest recognition of outstanding scholarship, leadership in student activities, and service—and this year, another eight were honored. -

An Analysis of the American Outdoor Sport Facility: Developing an Ideal Type on the Evolution of Professional Baseball and Football Structures

AN ANALYSIS OF THE AMERICAN OUTDOOR SPORT FACILITY: DEVELOPING AN IDEAL TYPE ON THE EVOLUTION OF PROFESSIONAL BASEBALL AND FOOTBALL STRUCTURES DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Chad S. Seifried, B.S., M.Ed. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Donna Pastore, Advisor Professor Melvin Adelman _________________________________ Professor Janet Fink Advisor College of Education Copyright by Chad Seifried 2005 ABSTRACT The purpose of this study is to analyze the physical layout of the American baseball and football professional sport facility from 1850 to present and design an ideal-type appropriate for its evolution. Specifically, this study attempts to establish a logical expansion and adaptation of Bale’s Four-Stage Ideal-type on the Evolution of the Modern English Soccer Stadium appropriate for the history of professional baseball and football and that predicts future changes in American sport facilities. In essence, it is the author’s intention to provide a more coherent and comprehensive account of the evolving professional baseball and football sport facility and where it appears to be headed. This investigation concludes eight stages exist concerning the evolution of the professional baseball and football sport facility. Stages one through four primarily appeared before the beginning of the 20th century and existed as temporary structures which were small and cheaply built. Stages five and six materialize as the first permanent professional baseball and football facilities. Stage seven surfaces as a multi-purpose facility which attempted to accommodate both professional football and baseball equally. -

Field Hockey TEAM CHAMPIONS Year Championship Site Reg

Field Hockey TEAM CHAMPIONS Year Championship Site Reg. Season Champion Champion Coach 2016 Pacific Field Hockey Turf, Stockton, Calif. East - Albany; West - Stanford/Pacific Stanford Tara Danielson 2015 Alumni Turf, Albany, N.Y. East - Albany/Maine; West - Stanford/Pacific Albany Phil Sykes 2014 Alumni Turf, Albany, N.Y. Albany Albany Phil Sykes 2013 Memorial Field, Durham, N.H. New Hampshire New Hampshire Robin Balducci 2012 Memorial Field, Durham, N.H. New Hampshire Albany Phil Sykes 2011 Memorial Field, Durham, N.H. New Hampshire/Boston University New Hampshire Robin Balducci 2010 Memorial Field, Durham, N.H. New Hampshire Albany Phil Sykes 2009 Alumni Turf Field, Albany, N.Y. Albany/Boston University Boston University Sally Starr 2008 Alumni Turf Field, Albany, N.Y. Albany Albany Phil Sykes 2007 Jack Barry Field, Cambridge, Mass. Boston University Boston University Sally Starr 2006 Jack Barry Field, Cambridge, Mass. Boston University/Albany Boston University Sally Starr 2005 Jack Barry Field, Cambridge, Mass. Boston University/Maine Boston University Sally Starr 2004 Jack Barry Field, Cambridge, Mass. Boston University Northeastern Cheryl Murtagh 2003 Sweeney Field, Boston, Mass. Northeastern Northeastern Cheryl Murtagh 2002 Sweeney Field, Boston, Mass. Northeastern/New Hampshire Northeastern Cheryl Murtagh 2001 Sweeney Field, Boston, Mass. Northeastern Northeastern Cheryl Murtagh 2000 Nickerson Field, Boston, Mass. New Hampshire Boston University Sally Starr 1999 Nickerson Field, Boston, Mass. Boston University Boston University Sally Starr 1998 Hofstra Stadium, Hempstead, N.Y. Northeastern New Hampshire Robin Balducci 1997 Parsons Field, Boston, Mass. Northeastern Northeastern Cheryl Murtagh 1996 Nickerson Field, Boston, Mass. Boston University Northeastern Cheryl Murtagh 1995 Parsons Field, Boston, Mass. -

NEW ENGLAND Patriots at New York Jets Media Schedule GAME SUMMARY NEW ENGLAND PATRIOTS (11-3) at NEW YORK JETS (3-11) WEDNESDAY, DECEMBER 17 Sunday, Dec

REGULAR SEASON WEEK 16 NEW ENGLAND patriots at new york jets Media schedule GAME SUMMARY NEW ENGLAND PATRIOTS (11-3) at NEW YORK JETS (3-11) WEDNESDAY, DECEMBER 17 Sunday, Dec. 21, 2014 • MetLife Stadium (82,566) • 1:00 p.m. ET 8:30 a.m. Media Check-In (Ticket Office) The New England Patriots clinched the AFC East for the sixth straight season with a 41-13 9:00-9:15 a.m. Bill Belichick Press Conference victory over the Miami Dolphins at Gillette Stadium last Sunday, tied for the second-longest 10:00 a.m. Tom Brady Press Conference streak in NFL history. Only the Los Angeles Rams (seven, 1973-79) posted a longer streak. Approx. 10:45 a.m. Jets Head Coach Rex Ryan The Patriots are the first team in NFL history to win 11 division championships in a 12-year Conference Call span. This week, New England can clinch a first-round bye with a win and can secure home-field Approx. 11:45 a.m. Media Access at Practice advantage throughout the AFC Playoffs with a win and a Denver loss. Approx. 2:00-2:45 p.m. Patriots Player Availability The Patriots have now qualified for the playoffs 22 times in their 55-year history. The Patri- (Open Locker Room) ots have earned 16 playoff berths in the 21 seasons since Robert Kraft purchased the team in 1994, a dramatic contrast to the six total playoff berths that the team earned in its first 34 TBD Jets Player TBD years of existence. New England has won 14 AFC East crowns under Kraft’s leadership. -

Fenway Park, Then Visit the Yankees at New Yankee Stadium

ISBN: 9781640498044 US $24.99 CAN $30.99 OSD: 3/16/2021 Trim: 5.375 x 8.375 Trade paperback CONTENTS HIT THE ROAD ..................................................................... 00 PLANNING YOUR TRIP ......................................................... 00 Where to Go ........................................................................................................... 00 When to Go ............................................................................................................. 00 Before You Go ........................................................................................................ 00 TOP BALLPARKS & EXPERIENCES ..................................... 00 The East Coast ....................................00 The East Coast Road Trip .....................................................................................00 Boston W Red Sox .................................................................................................00 New York W Yankees and Mets .........................................................................00 Philadelphia W Phillies ........................................................................................ 00 Baltimore W Orioles ..............................................................................................00 Washington DC W Nationals ............................................................................. 00 Florida and the Southeast ........................00 Florida and the Southeast Road Trip ..............................................................00 -

2015 BOSTON UNIVERSITY Men's Soccer Ncaa NOTES

2015 BOSTON UNIVERSITY mEN’S SOccER NcAA NOTES 2015 BU SCHEDULE AND RESULTS AUGUST (1-1-0 = H: 0-1, A: 1-0) Fri. 28 at Fordham OT W, 2-1 Mon. 31 BOSTON COLLEGE L, 2-3 SEPTEMBER (4-1-1 = H: 3-0-1, A: 1-1-0) Tue. 8 SIENA W, 1-0 Sun. 13 at Massachusetts W, 2-1 GAME #20 Sat. 19 at Princeton L, 1-2 Thu. 24 HARVARD W, 3-0 Thursday, Nov. 19 - NCAA First Round Sun. 27 BUCKNELL* 2OT T, 1-1 12:30 p.m. - Joseph J. Morrone Stadium - Storrs, Conn. Wed. 30 UMASS LOWELL W, 1-0 Boston University (12-5-2, 6-1-2 PL) at UConn (9-5-6, 3-3-2 AAC) OCTOBER (5-2-1 = H: 2-1-1, A: 3-1-1 Sat. 3 at American* W, 1-0 WATCH: UConnHuskies.com Wed. 7 at Colgate* OT W, 1-0 Sat. 10 LOYOLA MARYLAND* W, 2-1 THE GAME Huskies, claiming a 3-1 victory • In a match-up of NCAA at- before coincidentally falling at Tue. 13 at Brown L, 2-0 large recipients, the Boston Indiana, the next scheduled Sat. 17 at Lafayette* W, 1-0 University men’s soccer team opponent for the Thursday Tue. 20 ALBANY W, 3-0 will visit UConn for the NCAA afternoon winner. Sat. 24 LEHIGH* OT L, 2-3 First Round on Thurs., Nov. 19. • In their last NCAA appearance, • First kick was originally All-Time Series: UConn leads, 31-12-3 the Terriers opened with a 1-0 Wed. -

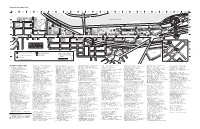

Charles River Campus Map 2010/2011 Campus Guide

Charles River Campus Map 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 Cambridge MASSACHUSETTS AVE. SOLDIERS FIELD ROAD To E A MEMORIAL DRIV A 619 M A 285 SS 120 AC 512 100 300 HU C3 S BOSTON UNIVERSITY BRIDGE ET TS ASHFORD ST. T 277 U R 519 NickersonField NP B 33 IK B BU E 531 Softball P STORROW DRIVE CHARLESGATE EAST Field 11 P 53 CHARLESGATE WEST 2 275 53 91 10 83–65 61 GARDNER ST. P 147–139 115 117 Alpert 121 125 131 P 185–167 133 RALEIGH 209–191 153 157 163 32 225 213 273 Mall 632 610 481 BAY STATE ROAD DEERFIELD ST. 70 6056 25 P 765 P 96 94–74 264 C 771 270 172–152 118–108 C 122 767 124 236–226 214–182 140 128 P 19 176 178 656 1 660 648 735 2 565 BEACON STREET To Downtown 949 925 915 P 775 GRANBY ST. Boston 1 595 P 575 1019 P P 985 881 871 855 725 705 685 675 621 SILBER WAY P ALCORN ST. 755 745 635 C4 541–533 BUICK ST. BABCOCK ST. HARRY AGGANIS WAY HARRY M1 629 625 C6 UNIVERSITY RD. C5 MALVERN ST. MALVERN P AVENUE COMMONWEALTH AVENUE Kenmore LTH COMMONWEALTH AVENUE A Square E M2 M3 M4 D W D N 940 928 890–882 846–832 808 766–730 700 P 602 580 918 115 1010 728–718 710 704 500 O P P P M 940W M M FU MOUNTFORT ST. -

Michele Uhlfelder

Front Row (L to R): Amanda Soto, Dana Lindsay, Bess Siegfried, Julie Mithun, Liz Piselli, Julie Christy, Bri Ned, Amanda Schwab, Alicia Soto, Amy Stillwell, Claire Hubbard. Row 2: Assistant Coach Randall Goldsborough, Lauren Schmidt, Katharine Fox, Anna Brown, Michelle DeChant, Charity Fluharty, Eleanor Foote, Bryanne Gilkinson, Leigh Lucas, Maris Perlman, Vicky Fanslow, Laura Shane, Strength and Conditioning Coach Dena Floyd. Row 3: Assistant Coach Kylee (Reade) White, Sarah Blahnik, Ariana Parasco, Megan McClain, Jessica Verrilli, Bis Fries, Polly Brown, Rachel Dyke, Melissa Vogelsong, Jamie Nesbitt, Daphne Patterson, Head Coach Michele Uhlfelder. 2007 Women’s Lacrosse 2007 Stanford Lacrosse Guide Stanford Quick Facts .............................................................................................. 1 Media Information ................................................................................................. 1 2007 Season Preview ........................................................................................... 2-3 Head Coach Michele Uhlfelder ......................................................................... 4-5 Stanford Lacrosse Coaching Staff ...................................................................... 5-6 2007 Roster .............................................................................................................. 7 Inside Stanford Lacrosse ..................................................................................... 8-9 Returning Player Profiles ............................................................................... -

Guide to the Amos Alonzo Stagg Papers 1866-1964

University of Chicago Library Guide to the Amos Alonzo Stagg Papers 1866-1964 © 2006 University of Chicago Library Table of Contents Descriptive Summary 3 Information on Use 3 Access 3 Citation 3 Biographical Note 3 Scope Note 5 Related Resources 5 Subject Headings 6 INVENTORY 6 Series I: Correspondence, 1884-1964 6 Subseries 1: Family 6 Subseries 2: General, 1884-1964 6 Subseries 3: U. of C. Correspondence - Administrative and Faculty 14 Subseries 4: U. of C. Athletic Department 17 Series II: University Of Chicago, Department Of Physical Culture And Athletics,25 1892-1933 Series III: Football 32 Series IV: Athletics-General 60 Series V: Athletic Associations 81 Series VI: Post-Chicago Coaching Positions 89 Series VII: Biographical 94 Series VIII: Scrapbooks, Notebooks, and Albums 105 Subseries 1: University of Chicago Athletic Scrapbooks 107 Subseries 2: College of the Pacific Athletic Scrapbooks 144 Subseries 3: Amos Alonzo Stagg Career and Personal Scrapbooks 147 Subseries 4: Amos Alonzo Stagg Pre-Chicago Personal Scrapbooks 150 Subseries 5: Amos Alonzo Stagg Football Notebooks 152 Subseries 6: Duplicate Football Notebooks 161 Subseries 7: Scouting and University of Chicago Athletics Notebooks 163 Subseries 8: Miscellaneous Notebooks 168 Subseries 9: Photo Albums 169 Series IX: Books, Journals and Ephemera 175 Subseries 1: Books and Journals 175 Subseries 2: Ephemera 178 Descriptive Summary Identifier ICU.SPCL.STAGG Title Stagg, Amos Alonzo. Papers Date 1866-1964 Size 384 linear feet (339 boxes) Repository Special Collections Research Center University of Chicago Library 1100 East 57th Street Chicago, Illinois 60637 U.S.A. Abstract Amos Alonzo Stagg was first Athletic Director and football coach for the University of Chicago from 1892-1933 and football coach for the College of the Pacific from 1933-1946. -

Meet. Eat. Play. Stay. Educate. Celebrate

Meet. Eat. Play. Stay. Educate. Celebrate. Events & Conferences at BU Why BU? “I have worked with BU Events & Conferences for over 25 years and For starters, a multitude of beautiful and unique have always receieved outstanding service and results. Their staff is venues to choose from. Next, you’re in the expert hands of BU’s always professional, courteous, professional staff; after they help you select the ideal setting, they and helpful. They take care of all of the small details that make these will help tailor all the details to meet your needs and to create an events successful. Cannon Financial Institute is proud to be a long- effortless and perfect event. time partner and look forward to continuing our relationiship well into Also, BU offers just about every resource, amenity, and service the future.” —Andy C., Cannon Financial Institute you could need, including state-of-the-art electronics, A/V experts, exceptional catering, and overnight accommodations. Finally, there is the University itself, an exciting destination with a beautiful setting on the Charles River in the heart of Boston that is easily accessed by car or public transportation. In short, Boston University offers a great location, lots of options, customized attention, and superior service for your event. For 5, 50, 500, or 5,000 Suites and apartments, which are or design a menu exclusively for Choosing the right facility for your event available for adults, feature air your event. makes a strong, positive statement. conditioning, single-occupancy bedrooms Other convenient dining options include Fortunately, you’ve come to the right place. -

Intercollegiate Football Researchers Association™

INTERCOLLEGIATE FOOTBALL RESEARCHERS ASSOCIATION ™ The College Football Historian ™ Reliving college football’s unique and interesting history—today!! ISSN: 2326-3628 [June 2014… Vol. 7, No. 5] circa: Jan. 2008 Tex Noël, Editor ([email protected]) Website: http://www.secsportsfan.com/college-football-association.html Disclaimer: Not associated with the NCAA, NAIA, NJCAA or their colleges and universities. All content is protected by copyright© by the author. FACEBOOK: https://www.facebook.com/theifra In honor of D-Day, IFRA salutes and thanks our true American Heroes—the U.S. Military. A number of our subscribers have served in the Armed Forces—and we thank you for your service to our country. And if reader of this issues was in Normandy that day—or WW II— we say a Texas-size thank you. “The supreme quality for leadership is unquestionably integrity. Without it, no real success is possible, no matter whether it is on a section gang, a football field, in an army, or in an office.” -- Dwight D. Eisenhower (1890-1969); Military Commander and 34th US President and football at West Point, 1912-14). Editor’s Note: I forgot to site this source; but this seems like the ideal time to use it. When Pvt. Dick Weber, Lawrence, Mass., halfback on the 1941 St. Louis university football team, was sent to a west coast army camp, he spent five days looking for a former teammate, Ray Schmissour, Belleville, Ill. Then he found Schmissour, a guard on the 1940 Billiken squad, was living only two buildings from his own quarters. * * * Attached to this month’s issue of TCFH, will be Loren Maxwell’s Classifying College Football Teams from 1882 to 1972, Revisited The College Football Historian-2 - Used by permission of the author Football History: A Stagg Party In Forest Grove By Blake Timm '98, Sports Information Director (Pacific University) Amos Alonzo Stagg, "The Grand Old Man Of Football," joins his son, former Pacific Head Coach Dr.