A Cross-Cultural Study of Names and the Unearthing of Naming Practices in Three Ethnic Groups in Nigeria Pjaee, 18 (4) (2021)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Was Life Like in the Ancient Kingdom of Benin? Today’S Enquiry: Why Is It Important to Learn About Benin in School?

History Our main enquiry question this term: What was life like in the Ancient Kingdom of Benin? Today’s enquiry: Why is it important to learn about Benin in school? Benin Where is Benin? Benin is a region in Nigeria, West Africa. Benin was once a civilisation of cities and towns, powerful Kings and a large empire which traded over long distances. The Benin Empire 900-1897 Benin began in the 900s when the Edo people settled in the rainforests of West Africa. By the 1400s they had created a wealthy kingdom with a powerful ruler, known as the Oba. As their kingdom expanded they built walls and moats around Benin City which showed incredible town planning and architecture. What do you think of Benin City? Benin craftsmen were skilful in Bronze and Ivory and had strong religious beliefs. During this time, West Africa invented the smelting (heating and melting) of copper and zinc ores and the casting of Bronze. What do you think that this might mean? Why might this be important? What might this invention allowed them to do? This allowed them to produced beautiful works of art, particularly bronze sculptures, which they are famous for. Watch this video to learn more: https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/topics/zpvckqt/articles/z84fvcw 7 Benin was the center of trade. Europeans tried to trade with Benin in the 15 and 16 century, especially for spices like black pepper. When the Europeans arrived 8 Benin’s society was so advanced in what they produced compared with Britain at the time. -

The Perception of Edo People on International and Irregular Migration

THE PERCEPTION OF EDO PEOPLE ON INTERNATIONAL AND IRREGULAR MIGRATION BY EDO STATE TASK FORCE AGAINST HUMAN TRAFFICKING (ETAHT) Supported by DFID funded Market Development Programme in the Niger Delta being implemented by Development Alternatives Incorporated. Lead Consultant: Professor (Mrs) K. A. Eghafona Department Of Sociology And Anthropology University Of Benin Observatory Researcher: Dr. Lugard Ibhafidon Sadoh Department Of Sociology And Anthropology University Of Benin Observatory Quality Control Team Lead: Okereke Chigozie Data analyst ETAHT Foreword: Professor (Mrs) Yinka Omorogbe Chairperson ETAHT March 2019 i List of Abbreviations and Acronyms AHT Anti-human Trafficking CDC Community Development Committee EUROPOL European Union Agency for Law Enforcement Cooperation (formerly the European Police Office and Europol Drugs Unit) ETAHT Edo State Task Force Against Human Trafficking HT Human trafficking IOM International Organization for Migration LGA Local Government Area NAPTIP National Agency For Prohibition of Traffic In Persons & Other Related Matters NGO Non-Governmental Organization SEEDS (Edo) State Economic Empowerment and Development Strategy TIP Trafficking in Persons UN United Nations UNODC United Nations Office on Drug and Crime USA United States of America ii Acknowledgements This perception study was carried out by the Edo State Taskforce Against Human Trafficking (ETAHT) using the service of a consultant from the University of Benin Observatory within the framework of the project Counter Trafficking Initiative. We are particularly grateful to the chairperson of ETAHT and Attorney General of Edo State; Professor Mrs. Yinka Omorogbe for her support in actualizing this project. The effort of Mr. Chigozie Okereke and other staff of ETAHT who provided assistance towards the actualization of this task is immensely appreciated. -

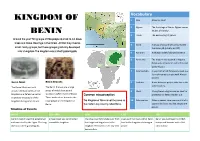

Kingdom of Benin Is Not the Same As 10 Colonisation When Invaders Take Over Control of a Benin

KINGDOM OF Vocabulary 1 Oba A king or chief. 2 Ogisos The first kings of Benin. Ogisos means BENIN ‘Rulers of the Sky’. 3 Trade The exchanging of goods. Around the year 900 groups of Edo people started to cut down trees and make clearings in the forest. At first they lived in 4 Guild A group of people who all complete small family groups, but these groups gradually developed the same job (usually a craft). into a kingdom. The kingdom was called Igodomigodo. 5 Animism A religion widely followed in Benin. 6 Benin city The modern city located in Nigeria. Previously, it has been called Edo and Igodomigodo. 7 Cowrie shells A sea shell which Europeans used as a form of money to trade with African leaders. Benin Moat Benin Bronzes 8 Civil war A war between people who live in the same country. The Benin Moat was built The Benin Bronzes are a large around the boundaries of the group of metal plaques and 9 Moat A long trench dug around an area for kingdom as a defensive barrier sculptures (often made of brass). Common misconception protection to keep invaders out. to protect the people of the These works of art decorate the kingdom during times of war. royal palace of the Kingdom of The Kingdom of Benin is not the same as 10 Colonisation When invaders take over control of a Benin. the modern day country called Benin. country by force, and live among the people. Timeline of Events 900 AD 900—1460 1180 1700 1897 Benin Kingdom was first established A huge moat was constructed The Oba royal family take over from A series of civil wars within Benin Benin was destroyed by British and was ruled by the Ogiso. -

Oil and the Urban Question

NIGER DELTA ECONOMIES OF VIOLENCE WORKING PAPERS Working Paper No. 8 OIL AND THE URBAN QUESTION Fuelling Violence and Politics in Warri Marcus Leton Program Offi cer Our Niger Delta (OND), Port Harcourt, Nigeria 2006 Institute of International Studies, University of California, Berkeley, USA The United States Institute of Peace, Washington DC, USA Our Niger Delta, Port Harcourt, Nigeria OIL AND THE URBAN QUESTION: FUELLING POLITICS AND VIOLENCE IN WARRI Marcus Leton1 Program Officer Our Niger Delta Port Harcourt, Nigeria Who owns Warri Township? This is a multi-million naira question… Is it the Itsekiri, the Agbassa Urhobo or the Ijaw? J.O.S.Ayomike, A History of Warri, Benin, Ilupeju Press, 1988, p.58. [Warri] is an age-long conflict. Legally, Warri has been judged to be Itsekiri owned….That the legal system has not been able to effect a permanent settlement of conflict claims of ownership is seen from the bloody clashes….in the past few years. The conflict has claimed over 3000 lives, displaced thousands, and destroyed property worth several billions of naira. V. Isumonah and J.Gaskiya, Ethnic Groups and Conflicts in Nigeria: The South-South Zone of Nigeria, University of Ibadan, 2001, pp.63-64. The Warri crisis is in many respects a classic example of a “resource war”. Human Rights Watch. The Warri Crisis: Fuelling the Violence, November 2003, p.26. INTRODUCTION Warri represents one of the most important. and most complex. sites of ‘petro- violence’ in all of Nigeria. The current crisis in the oil-producing Niger Delta that emerged in late 2005 with the appearance of the Movement for the Emancipation of Niger Delta (MEND) and a series of abductions and attacks on oil installations, is merely the most recent expression of a long simmering conflict that has engulfed both Warri city and its surrounding hinterlands. -

Folktale Tradition of the Esan People and African Oral Literature

“OKHA”: FOLKTALE TRADITION OF THE ESAN PEOPLE AND AFRICAN ORAL LITERATURE 1ST IN THE SERIES OF INAUGURAL LECTURES OF SAMUEL ADEGBOYEGA UNIVERSITY OGWA, EDO STATE, NIGERIA. BY PROFESSOR BRIDGET O. INEGBEBOH B.A. M.A. PH.D (ENGLISH AND LITERATURE) (BENIN) M.ED. (ADMIN.) (BENIN), LLB. A.A.U (EKPOMA), BL. (ABUJA) LLM. (BENIN) Professor of English and Literature Department of Languages Samuel Adegboyega University, Ogwa. Wednesday, 11th Day of May, 2016. PROFESSOR BRIDGET O. INEGBEBOH B.A. M.A. PH.D (ENGLISH AND LITERATURE) (BENIN) M.ED. (ADMIN.) (BENIN), LLB. A.A.U (EKPOMA), BL. (ABUJA) LLM. (BENIN) 2 “OKHA”: FOLKTALE TRADITION OF THE ESAN PEOPLE AND AFRICAN ORAL LITERATURE 1ST IN THE SERIES OF INAUGURAL LECTURES OF SAMUEL ADEGBOYEGA UNIVERSITY OGWA, EDO STATE, NIGERIA. BY BRIDGET OBIAOZOR INEGBEBOH B.A. M.A. PH.D (ENGLISH AND LITERATURE) (BENIN) M.ED. (ADMIN.) (BENIN), LLB. A.A.U (EKPOMA), BL. (ABUJA) LLM. (BENIN) Professor of English and Literature Department of Languages Samuel Adegboyega University, Ogwa. Wednesday, 11th Day of May, 2016. 3 “OKHA”: FOLKTALE TRADITION OF THE ESAN PEOPLE AND AFRICAN ORAL LITERATURE Copyright 2016. Samuel Adegboyega University, Ogwa All Rights Reserved No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in any retrieval system or by any means, photocopying, electronic, mechanical, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of Samuel Adegboyega University, Ogwa/Publishers. ISBN: Published in 2016 by: SAMUEL ADEGBOYEGA UNIVERSITY, OGWA, EDO STATE, NIGERIA. Printed by: 4 Vice-Chancellor, Chairman and members of the Governing Council of SAU, The Management of SAU, Distinguished Academia, My Lords Spiritual and Temporal, His Royal Majesties here present, All Chiefs present, Distinguished Guests, Representatives of the press and all Media Houses present, Staff and Students of Great SAU, Distinguished Ladies and Gentlemen. -

Indigenous Oral Poetry in Nigeria As a Tool for National Unity

© Kamla-Raj 2011 J Communication, 2(2): 83-91 (2011) Indigenous Oral Poetry in Nigeria as a Tool for National Unity Luke Eyoh Department of English, University of Uyo, Uyo, Nigeria GSM: 08023569440; E-mail: lukeeyoh@ yahoo.com KEYWORDS Insights. Similarities. Ethnic. Frontiers. Development ABSTRACT The paper adopts the stylistic critical approach to the study of selected ethnic oral poetry in Nigeria. Its findings disclose ample insights into copious similarities in interests, thoughts, worldviews and values across the various ethnic groups in Nigeria. These findings constitute an effective tool for national integration, unity and development. The paper recommends the preservation, propagation, teaching and learning of Nigerian oral poetry across ethnic frontiers with emphasis on its unifying properties as a means to achieving national unity and development in the country. INTRODUCTION Indicator of Cultural Unity in Nigeria: Similari- ties in Ibibio and Ijo/Urhobo Animal Symbol- The paper explores and illuminates indi- ism in J. P. Clark-Bekederemo’s Poetry” genous oral poetry in Nigeria as a tool for na- published in Essays in Language and Literature tional unity. It comprises six sections, section one in Honour of Ime Ikiddeh at 60 reveals, through being this introduction. Section two focuses on ample research, copious similarities in animal a review of literature germane to the study, three symbolism in Ibibio, Ijo/Urhobo and other Ni- on the critical approach used for the study and gerian cultures. The work suggests that reading four on ten (10) selected ethnic poetic forms in Nigerian poems “rich in cross-cultural animal Nigeria. The ten (10) items, obtained from symbolism stimulates and sustains national con- resource persons and secondary sources, are sciousness and unity in Nigeria” (61). -

Journal of African Studies and Sustainable Development. ISSN: 2630-7065 (Print) 2630-7073 (E)

Journal of African Studies and Sustainable Development. ISSN: 2630-7065 (Print) 2630-7073 (e). Vol.2 No. 8, 2019 TRADITIONAL JUDICIAL SYSTEM IN URHOBOLAND Atake, Odjuvwuederie John Department of history and international studies Faculty of arts University of uyo, uyo DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.27700.81281 Abstract The aim of this study is to examine the traditional judicial system in Urhoboland. Also, this study highlights the traditional administration in the precolonial and colonial period. The essence of the study study is to mirror the changes and impacts of modernity in the Urhobo society particularly the judicial system with the advent of Colonialism by the British. A descriptive method was used to reflect the detail information about the traditional judicial system in urhobo land. The study is a discourse on the Urhobo social system, role of traditional institutions in Urhobo judicial system, the courts and the applicable laws as well as traditional administration of justice. The judicial system and practices was, and still regulates the behaviour of people to maintain social order. The system requires different types of courts as instruments for the resolution of conflict and administration of justice. These courts are inclusive of the Upper Court (Egware r‟Orho) and Lower Court (Egware r‟Egodo): Court of the Family (Egware r‟Ekru or Orua): Court of the Quarter(Egware r‟Uduvwu): Court of the Village(Egware r‟Oko or Ighwre): Court of the Youths (Egware r‟Ighele): Court of the Women Folk(Egware r‟Eghweya) and Special Court Against Theft(Egware r‟Idigbu. However, the highest body which is called in Ovie-in-Council (Ovie -King, Otota- Spokesman and selected Chiefs) take decision on cruicial and major isssues. -

(Ekpo) Masquerade in Edo Belief: the Socio – Economic Relevance

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 19, Issue 1, Ver. VIII (Jan. 2014), PP 64-68 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org (Ekpo) Masquerade In Edo Belief: The Socio – Economic Relevance T. O. Ebhomienlen and M. O. Idemudia Abstract: This paper examines EKPO (masquerade) among the Edo and its socio-economic contributions to development. It sees EKPO Cult and its Festivals as a vehicle for social stability and cohesion. Masquerades features prominently in African traditional religions. It is not out of place to assert that the preponderance of masquerades in most African Socio- religious Cult is a reflection of their unitary mode of expressing that which they perceive and thought of the divine or out of the sphere of humans. The African recognizes the place of the ancestors and gives them appropriate veneration and reverence as they are seen as human representatives in the spirit world. This paper further seeks to reveal that masquerade is one of the ways the African use to convey the continuous participation of the ancestors in human affairs. Hence, the Yoruba and the Edo conceive of masquerades as visible symbolic representation of the ancestors. They consider them as sacred and special cult is accorded them. To both people, Masquerade is a bridge of the chasm between the living and the living dead. The literature also discusses that masquerade though a spiritual phenomenon is also a vehicle for Socio- economic development among the Edo people. The thrust of this paper is in this regards. A comparative and evaluative method is adopted in the crux of the discourse. -

Nigeria – Researched and Compiled by the Refugee Documentation Centre of Ireland on 22 October 2010 Information on the Followi

Nigeria – Researched and compiled by the Refugee Documentation Centre of Ireland on 22 October 2010 Information on the following: 1. The similarities (if any) between Urhobo (alternatively “Sobo”) and Itsekiri (alt. “Isekiri”; “Ishekiri”; etc.) language; 2. The similarities (if any) between Urhobo and Itsekiri ethnicities/cultures/customs; 3. The distribution of Urhobo and Itsekiri populations; including whether these groups live in the same towns/regions of Nigeria; 4. Whether there is any information on whether Itsekiri speakers can or do speak Urhobo, and vice versa. 5. Whether there is conflict/co-operation between Urhobo and Itsekiri people (groups or individuals), and to what extent. A page on the Delta State Tourism website states: “There are five ethnic groups in Delta State, namely Anioma, Ijaw, Isoko, Itsekiri and Urhobo. Deltans speak a variety of languages and dialects but have nearly identical customs, culture and occupations. These are easily identified in the courts of most traditional rulers across the state.” (Delta State Tourism (undated) Delta State: The Big Heart) An entry on the Urhobo in The Peoples of Africa – An Ethnohistorical Dictionary states: “The Urhobo (Uhrobo, Biotu, and the pejorative Sobo) people live in Bendel State in Nigeria, primarily in the Western and Eastern Urhobo divisions. They are closely related to the neighboring Edo people.” (Olson, James S. (1996) The Peoples of Africa – An Ethnohistorical Dictionary. Westport, Greenwood Press. p.578) A page on the Urhobo Association of New York, New Jersey & Connecticut website, in a paragraph headed “People”, states: “The Urhobo people are located in the present Delta State of Nigeria. -

Journal of Environment and Culture

Environment and Culture A Volume 11 Number 1, June 2014 & Volume 11 Number 2, December 2014 Journal of Environment and Culture Volume 11 Number 1, June 2014. Editorial Board C. A. Folorunso Editor-in-Chief A. S. Ajala Editorial Secretary’ and Book Reviewer Editorial Executives O. B. Lawuyi Publishing philosophy P. A. Oyelaran Journal of Environment and J. O. Aleru Culture promotes the R. A. Alabi publication of issues, research, and comments Consultants and Advisory Board connected with the way, M. A. Sowunmi, P. Sinclair, N. David, culture determines, Stephen Shennan, Claire Smith, G. Pwiti, regulates, and accounts for A. Oke, O. O. Areola and M. C. Emerson. the environment in Africa or any other parts of the Editorial Address world. It is interested in the Editor-in-Chief application of knowledge, Journal of Environment and Culture research and science to a Department of Archaeology and healthy, stable, am Anthropology, University of Ibadan sustaining humaiJ Ibadan, Nigeria. environment.,, C e-mail: [email protected] ISSN 1597 2755 The Department of Archaeology and Antrhopology, University of Ibadan, publishes the Journal of Environment and Culture twice in the year, in June and December. The subscription rates are N3000 a year for local institutions and N 1500 for individuals. Foreign institutions will pay US$50 and individuals, US$20. Changes in address should be sent to Journal of Environment and Culture, Department of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of Ibadan, Nigeria. Swift Print Limited *X Junta Osogbo, Nigeria Volume 11 Number 1, June 2014. Contents A Reconsideration of the Ora Benin Relationship , -1 Pogoson- Ohioma Ifounu ... -

Gst201 Nigerian Peoples and Culture

COURSE GUIDE GST201 NIGERIAN PEOPLES AND CULTURE Course Team Dr. Cyrille D. Ngamen Kouassi (Developer/ Writer) - IGBINEDION Prof. Bertram A. Okolo (Course Editor) - UNIBEN Prof. A.R. Yesufu (Programme Leader) - NOUN Prof. A.R. Yesufu (Course Coordinator) - NOUN NATIONAL OPEN UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA GST201 COURSE GUIDE National Open University of Nigeria Headquarters University Village Plot 91, Cadastral Zone Nnamdi Azikiwe Expressway Jabi, Abuja Lagos Office 14/16 Ahmadu Bello Way Victoria Island, Lagos e-mail: [email protected] website: www.nouedu.net Printed by: NOUN Press Printed 2017, 2019, 2021 ISBN: 978-058-425-0 All Rights Reserved ii GST201 COURSE GUIDE CONTENTS PAGE Introduction......................................................................................... iv What You Will Learn in This Course……………..………………… iv Course Aims....................................................................................... iv Course Objectives............................................................................... v Working through This Course............................................................. v Course Materials…………………………………………………….. v Study Units.......................................................................................... vi Textbooks and References…………………………………………... vii The Assignment File……………………………..………………….. vii The Presentation Schedule………………………………………….. vii Assessment......................................................................................... vii Tutor-Marked Assignment………………………………………….. -

The Uniqueness of Olomu and of Its King, HRM Richard L. Ogbon, Ohworode R’ Olomu by Professor Peter P

The Uniqueness of Olomu and of Its King, HRM Richard L. Ogbon, Ohworode R’ Olomu By Professor Peter P. Ekeh President, Urhobo Historical Society Personal Preamble Permit me to approach this grand subject-matter with a narrative of my personal encounter with Olomu. In 1947, I was in Standard II of British Colonial educational system at Catholic Central School, Okpara Inland. In a Geography class, there had been some discussion of the towns of Agbon clan. Then information came to us that Agbon, the eponymous ancestor of the Agbon people, was going to be worshipped within a day or two. Indeed, we saw the cow that was to be slaughtered for the sacrifice of the worship being led to the Agbon headquarters at Isiokoro, some two miles away from our School. Two of my friends and I decided to walk to Isiokoro to watch the events of the worship of Agbon. In the company of my two elementary school friends, I did watch the solemn events of the worship of Agbon in 1947. In my recollection, I was very much impressed with the seriousness of the worship. The adults, who carried out the functions of the sacrifice, and the elders from all Agbon towns, who were the presiding authorities, approached their work with intensity. The prayers for the welfare of Agbon people were remarkable. By far, however, what stood out to me in my vivid recollection were two related pronouncements. The first extraordinary announcement, for the mind of a school age boy anyway, was that the 1 head of the sacrificial cow would be sent to Isoko.