Project "Anima Veneziana". Antonio Vivaldi. Biography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Question of the Baroque Instrumental Concerto Typology

Musica Iagellonica 2012 ISSN 1233-9679 Piotr WILK (Kraków) On the question of the Baroque instrumental concerto typology A concerto was one of the most important genres of instrumental music in the Baroque period. The composers who contributed to the development of this musical genre have significantly influenced the shape of the orchestral tex- ture and created a model of the relationship between a soloist and an orchestra, which is still in use today. In terms of its form and style, the Baroque concerto is much more varied than a concerto in any other period in the music history. This diversity and ingenious approaches are causing many challenges that the researches of the genre are bound to face. In this article, I will attempt to re- view existing classifications of the Baroque concerto, and introduce my own typology, which I believe, will facilitate more accurate and clearer description of the content of historical sources. When thinking of the Baroque concerto today, usually three types of genre come to mind: solo concerto, concerto grosso and orchestral concerto. Such classification was first introduced by Manfred Bukofzer in his definitive monograph Music in the Baroque Era. 1 While agreeing with Arnold Schering’s pioneering typology where the author identifies solo concerto, concerto grosso and sinfonia-concerto in the Baroque, Bukofzer notes that the last term is mis- 1 M. Bukofzer, Music in the Baroque Era. From Monteverdi to Bach, New York 1947: 318– –319. 83 Piotr Wilk leading, and that for works where a soloist is not called for, the term ‘orchestral concerto’ should rather be used. -

The Double Keyboard Concertos of Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach

The double keyboard concertos of Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Waterman, Muriel Moore, 1923- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 25/09/2021 18:28:06 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/318085 THE DOUBLE KEYBOARD CONCERTOS OF CARL PHILIPP EMANUEL BACH by Muriel Moore Waterman A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 1 9 7 0 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of re quirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his judg ment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholar ship. In all other instances, however, permission must be obtained from the author. SIGNED: APPROVAL BY THESIS DIRECTOR This thesis has been approved on the date shown below: JAMES R. -

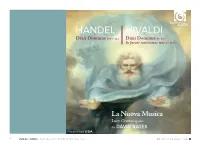

HANDEL VIVALDI Dixit Dominus Hwv 232 Dixit Dominus Rv 807 in Furore Iustissimae Irae Rv 626

HANDEL VIVALDI Dixit Dominus hwv 232 Dixit Dominus rv 807 In furore iustissimae irae rv 626 La Nuova Musica Lucy Crowe soprano dir. DAVID BATES 1 VIVALDI / HANDEL / Dixit Dominus / LA NUOVA MUSICA / David Bates HMU 807587 © harmonia mundi ANTONIO VIVALDI (1678-1741) Dixit Dominus rv 807 1 Dixit Dominus (chorus) 1’51 2 Donec ponam inimicos tuos (chorus) 3’34 3 Virgam virtutis tuae (soprano I) 3’06 4 Tecum principium in die virtutis (tenor I & II) 2’08 5 Juravit Dominus (chorus) 2’12 6 Dominus a dextris tuis (tenor I) 1’54 7 Judicabit in nationibus (chorus) 2’48 8 De torrente in via bibet (countertenor) 3’20 9 Gloria Patri, et Filio (soprano I & II) 2’27 10 Sicut erat in principio (chorus) 0’33 11 Amen (chorus) 2’47 In furore iustissimae irae rv 626* 12 In furore iustissimae (aria) 4’55 13 Miserationem Pater piissime (recitative) 0’39 14 Tunc meus fletus evadet laetus (aria) 6’58 15 Alleluia 1’28 GEORGE FRIDERIC HANDEL (1685-1759) Dixit Dominus hwv 232 16 Dixit Dominus (chorus) 5’49 17 Virgam virtutis tuae (countertenor) 2’49 18 Tecum principium in die virtutis (soprano I) 3’31 19 Juravit Dominus (chorus) 2’37 20 Tu es sacerdos in aeternum (chorus) 1’19 21 Dominus a dextris tuis (SSTTB & chorus) 7’32 22 De torrente in via bibet (soprano I, II & chorus) 3’55 23 Gloria Patri, et Filio (chorus) 6’33 La Nuova Musica *with Lucy Crowe soprano 12-15 DAVID BATES director Anna Dennis, Helen-Jane Howells, Augusta Hebbert, Esther Brazil, sopranos Christopher Lowrey, countertenor Simon Wall, Tom Raskin, tenors James Arthur, bass 2 VIVALDI / HANDEL / Dixit Dominus / LA NUOVA MUSICA / David Bates HMU 807587 © harmonia mundi Dixit Dominus ithin the Roman Catholic liturgy Psalm 109 aria in Vivaldi’s opera La fida ninfa (1732). -

9. Vivaldi and Ritornello Form

The HIGH BAROQUE:! Early Baroque High Baroque 1600-1670 1670-1750 The HIGH BAROQUE:! Republic of Venice The HIGH BAROQUE:! Grand Canal, Venice The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741) The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Antonio VIVALDI (1678-1741) Born in Venice, trains and works there. Ordained for the priesthood in 1703. Works for the Pio Ospedale della Pietà, a charitable organization for indigent, illegitimate or orphaned girls. The students were trained in music and gave frequent concerts. The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Thus, many of Vivaldi’s concerti were written for soloists and an orchestra made up of teen- age girls. The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO It is for the Ospedale students that Vivaldi writes over 500 concertos, publishing them in sets like Corelli, including: Op. 3 L’Estro Armonico (1711) Op. 4 La Stravaganza (1714) Op. 8 Il Cimento dell’Armonia e dell’Inventione (1725) Op. 9 La Cetra (1727) The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO In addition, from 1710 onwards Vivaldi pursues career as opera composer. His music was virtually forgotten after his death. His music was not re-discovered until the “Baroque Revival” during the 20th century. The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Vivaldi constructs The Model of the Baroque Concerto Form from elements of earlier instrumental composers *The Concertato idea *The Ritornello as a structuring device *The works and tonality of Corelli The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO The term “concerto” originates from a term used in the early Baroque to describe pieces that alternated and contrasted instrumental groups with vocalists (concertato = “to contend with”) The term is later applied to ensemble instrumental pieces that contrast a large ensemble (the concerto grosso or ripieno) with a smaller group of soloists (concertino) The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Corelli creates the standard concerto grosso instrumentation of a string orchestra (the concerto grosso) with a string trio + continuo for the ripieno in his Op. -

2257-AV-Venice by Night Digi

VENICE BY NIGHT ALBINONI · LOTTI POLLAROLO · PORTA VERACINI · VIVALDI LA SERENISSIMA ADRIAN CHANDLER MHAIRI LAWSON SOPRANO SIMON MUNDAY TRUMPET PETER WHELAN BASSOON ALBINONI · LOTTI · POLLAROLO · PORTA · VERACINI · VIVALDI VENICE BY NIGHT Arriving by Gondola Antonio Vivaldi 1678–1741 Antonio Lotti c.1667–1740 Concerto for bassoon, Alma ride exulta mortalis * Anon. c.1730 strings & continuo in C RV477 Motet for soprano, strings & continuo 1 Si la gondola avere 3:40 8 I. Allegro 3:50 e I. Aria – Allegro: Alma ride for soprano, violin and theorbo 9 II. Largo 3:56 exulta mortalis 4:38 0 III. Allegro 3:34 r II. Recitativo: Annuntiemur igitur 0:50 A Private Concert 11:20 t III. Ritornello – Adagio 0:39 z IV. Aria – Adagio: Venite ad nos 4:29 Carlo Francesco Pollarolo c.1653–1723 Journey by Gondola u V. Alleluja 1:52 Sinfonia to La vendetta d’amore 12:28 for trumpet, strings & continuo in C * Anon. c.1730 2 I. Allegro assai 1:32 q Cara Nina el bon to sesto * 2:00 Serenata 3 II. Largo 0:31 for soprano & guitar 4 III. Spiritoso 1:07 Tomaso Albinoni 3:10 Sinfonia to Il nome glorioso Music for Compline in terra, santificato in cielo Tomaso Albinoni 1671–1751 for trumpet, strings & continuo in C Sinfonia for strings & continuo Francesco Maria Veracini 1690–1768 i I. Allegro 2:09 in G minor Si 7 w Fuga, o capriccio con o II. Adagio 0:51 5 I. Allegro 2:17 quattro soggetti * 3:05 p III. Allegro 1:20 6 II. Larghetto è sempre piano 1:27 in D minor for strings & continuo 4:20 7 III. -

Concert Season 34

Concert Season 34 REVISED CALENDAR 2020 2021 Note from the Maestro eAfter an abbreviated Season 33, VoxAmaDeus returns for its 34th year with a renewed dedication to bringing you a diverse array of extraordinary concerts. It is with real pleasure that we look forward, once again, to returning to the stage and regaling our audiences with the fabulous programs that have been prepared for our three VoxAmaDeus performing groups. (Note that all fall concerts will be of shortened duration in light of current guidelines.) In this year of necessary breaks from tradition, our season opener in mid- September will be an intimate Maestro & Guests concert, September Soirée, featuring delightful solo works for piano, violin and oboe, in the spacious and acoustically superb St. Katharine of Siena Church in Wayne. Vox Renaissance Consort will continue with its trio of traditional Renaissance Noël concerts (including return to St. Katharine of Siena Church) that bring you back in time to the glory of Old Europe, with lavish costumes and period instruments, and heavenly music of Italian, English and German masters. Ama Deus Ensemble will perform five fascinating concerts. First is the traditional December Handel Messiah on Baroque instruments, but for this year shortened to 80 minutes and consisting of highlights from all three parts. Then, for our Good Friday concert in April, a program of sublime music, Bach Easter Oratorio & Rossini Stabat Mater; in May, two glorious Beethoven works, the Fifth Symphony and the Missa solemnis; and, lastly, two programs in June: Bach & Vivaldi Festival, as well as our Season 34 Grand Finale Gershwin & More (transplanted from January to June, as a temporary break from tradition), an exhilarating concert featuring favorite works by Gershwin, with the amazing Peter Donohoe as piano soloist, and also including rousing movie themes by Hans Zimmer and John Williams. -

1 Freitag, 18. Dezember 2015 SWR2 Treffpunkt Klassik – Neue Cds

1 Freitag, 18. Dezember 2015 SWR2 Treffpunkt Klassik – Neue CDs: Vorgestellt von Susanne Stähr Die maskierte Violine Antonio Vivaldi: Teatro alla moda Violinkonzerte RV 228, 282, 313, 314a, 316, 322, 323, 372a und 391; Sinfonia „L„Olimpiade”; Ballo primo de “Arsilda Refina di Ponto” Gli Incogniti, Amandine Beyer (Violine und Leitung) HMC 902221 Frau Musicas Himmelschöre Antonio Vivaldi: Geistliche Werke Gloria RV 589; Laetatus sum RV 607; Magnificat RV 610a; Lauda Jerusalem RV 609 Le Concert Spirituel, Hervé Niquet (Leitung) Alpha 222 Du angenehme Nachtigall Birds: Vögel in der Barockmusik Werke von Rameau, Händel, Arne, Vivaldi, Keiser, Couperin u.a. Dorothee Mields (Sopran), Stefan Temmingh (Blockflöte), The Genteman‟s Band, La Folia Barockorchester Deutsche Harmonia Mundi 88875141202 Atemloser Schöngesang Julia Lezhneva: Händel Frühe italienische Werke Julia Lezhneva (Sopran), Il Giardino Armonico, Giovanni Antonini (Leitung) Decca 478 9230 „Gross Wunderding sich bald begab“ A Wondrous Mystery Renaissancemusik zu Weihnachten Werke von Clemens non Papa, Johannes Eccard, Jacobus Gallus, Hans Leo Hassler, Hieronymus Praetorius, Michael Praetorius und Melchior Vulpius Stile Antico HMU 807575 Fürs Gemüt O heilige Nacht Romantische Chormusik zur Weihnachtszeit Werke von Franz Wüllner, Johannes Brahms, August von Othegraven, Gustav Schreck, Carl Loewe, Carl Gottlob Reißiger, Robert Fuchs, Max Bruch, Max Reger und Carl Reinthaler Dresdner Kammerchor, Hans-Christoph Rademann (Leitung) Carus 83.392 Am Mikrophon begrüßt Sie herzlich: Susanne Stähr. Sechsmal werden wir noch wach – doch was gibt es bis dahin nicht noch alles zu erledigen! Festtagseinkäufe, Weihnachtsbäckerei, letzte Geschenke, die besorgt werden wollen … Aber vielleicht können wir Ihnen wenigstens dabei helfen, mit ein paar CD-Empfehlungen nämlich. Sechs neue Platten möchte ich Ihnen gleich vorstellen: passend zur Saison mit viel Barockmusik, mit himmlischen Chören und englischen Stimmen. -

TCB Groove Program

www.piccolotheatre.com 224-420-2223 T-F 10A-5P 37 PLAYS IN 80-90 MINUTES! APRIL 7- MAY 14! SAVE THE DATE! NOVEMBER 10, 11, & 12 APRIL 21 7:30P APRIL 22 5:00P APRIL 23 2:00P NICHOLS CONCERT HALL BENITO JUAREZ ST. CHRYSOSTOM’S Join us for the powerful polyphony of MUSIC INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO COMMUNITY ACADEMY EPISCOPAL CHURCH G.F. Handel's As pants the hart, 1490 CHICAGO AVE PERFORMING ARTS CENTER 1424 N DEARBORN ST. EVANSTON, IL 60201 1450 W CERMAK RD CHICAGO, IL 60610 Domenico Scarlatti's Stabat mater, TICKETS $10-$40 CHICAGO, IL 60608 TICKETS $10-$40 and J.S. Bach's Singet dem Herrn. FREE ADMISSION Dear friends, Last fall, Third Coast Baroque’s debut series ¡Sarabanda! focused on examining the African and Latin American folk music roots of the sarabande. Today, we will be following the paths of the chaconne, passacaglia and other ostinato rhythms – with origins similar to the sarabande – as they spread across Europe during the 17th century. With this program that we are calling Groove!, we present those intoxicating rhythms in the fashion and flavor of the different countries where they gained popularity. The great European composers wrote masterpieces using the rhythms of these ancient dances to create immortal pieces of art, but their weight and significance is such that we tend to forget where their origins lie. Bach, Couperin, and Purcell – to name only a few – wrote music for highly sophisticated institutions. Still, through these dance rhythms, they were searching for something similar to what the more ancient civilizations had been striving to attain: a connection to the spiritual world. -

A Countertenor's Reference Guide to Operatic Repertoire

A COUNTERTENOR’S REFERENCE GUIDE TO OPERATIC REPERTOIRE Brad Morris A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC May 2019 Committee: Christopher Scholl, Advisor Kevin Bylsma Eftychia Papanikolaou © 2019 Brad Morris All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Christopher Scholl, Advisor There are few resources available for countertenors to find operatic repertoire. The purpose of the thesis is to provide an operatic repertoire guide for countertenors, and teachers with countertenors as students. Arias were selected based on the premise that the original singer was a castrato, the original singer was a countertenor, or the role is commonly performed by countertenors of today. Information about the composer, information about the opera, and the pedagogical significance of each aria is listed within each section. Study sheets are provided after each aria to list additional resources for countertenors and teachers with countertenors as students. It is the goal that any countertenor or male soprano can find usable repertoire in this guide. iv I dedicate this thesis to all of the music educators who encouraged me on my countertenor journey and who pushed me to find my own path in this field. v PREFACE One of the hardships while working on my Master of Music degree was determining the lack of resources available to countertenors. While there are opera repertoire books for sopranos, mezzo-sopranos, tenors, baritones, and basses, none is readily available for countertenors. Although there are online resources, it requires a great deal of research to verify the validity of those sources. -

Concierto Barroco: Estudios Sobre Música, Dramaturgia E Historia Cultural

CONCIERTO BARROCO Estudios sobre música, dramaturgia e historia cultural CONCIERTO BARROCO Estudios sobre música, dramaturgia e historia cultural Juan José Carreras Miguel Ángel Marín (editores) UNIVERSIDAD DE LA RIOJA 2004 Concierto barroco: estudios sobre música, dramaturgia e historia cultural de Juan José Carreras y Miguel Ángel Marín (publicado por la Universidad de La Rioja) se encuentra bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercial-SinObraDerivada 3.0 Unported. Permisos que vayan más allá de lo cubierto por esta licencia pueden solicitarse a los titulares del copyright. © El autor © Universidad de La Rioja, Servicio de Publicaciones, 2012 publicaciones.unirioja.es E-mail: [email protected] ISBN: 978-84-695-4053-4 Afinaban cuerdas y trompas los músicos de la orquesta, cuando el indiano y su servidor se instalaron en la penumbra de un palco. Y, de pronto, cesaron los martillazos y afinaciones, se hizo un gran silencio y, en el puesto de director, vestido de negro, violín en mano, apareció el Preste Antonio, más flaco y narigudo que nunca […] Metido en lo suyo, sin volverse para mirar a las pocas personas que, aquí, allá, se habían colocado en el teatro, abrió lentamente un manuscrito, alzó el arco —como aquella noche— y, en doble papel de director y de ejecutante impar, dio comienzo a la sinfonía, más agitada y ritmada —acaso— que otras sinfonías suyas de sosegado tempo, y se abrió el telón sobre un estruendo de color… Alejo Carpentier, Concierto barroco ÍNDICE PRÓLOGO . 11 INTRODUCCIÓN . 13 PARTE I 1. Juan José Carreras Ópera y dramaturgia . 23 Nota bibliográfica 2. Martin Adams La “dramatic opera” inglesa: ¿un imposible género teatral? . -

Vivaldi Antonio Da Quel Ferro Aria from the Opera Il Farnace Arranged for Voice and Piano F Minor Sheet Music

Vivaldi Antonio Da Quel Ferro Aria From The Opera Il Farnace Arranged For Voice And Piano F Minor Sheet Music Download vivaldi antonio da quel ferro aria from the opera il farnace arranged for voice and piano f minor sheet music pdf now available in our library. We give you 4 pages partial preview of vivaldi antonio da quel ferro aria from the opera il farnace arranged for voice and piano f minor sheet music that you can try for free. This music notes has been read 11970 times and last read at 2021-09-29 12:19:31. In order to continue read the entire sheet music of vivaldi antonio da quel ferro aria from the opera il farnace arranged for voice and piano f minor you need to signup, download music sheet notes in pdf format also available for offline reading. Instrument: Alto Voice, Voice Solo, Piano Accompaniment Ensemble: Mixed Level: Advanced [ Read Sheet Music ] Other Sheet Music Vivaldi Antonio Da Quel Ferro Aria From The Opera Il Farnace Arranged For Voice And Piano E Minor Vivaldi Antonio Da Quel Ferro Aria From The Opera Il Farnace Arranged For Voice And Piano E Minor sheet music has been read 12663 times. Vivaldi antonio da quel ferro aria from the opera il farnace arranged for voice and piano e minor arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 4 preview and last read at 2021-09-29 21:00:21. [ Read More ] Vivaldi Antonio Da Quel Ferro Aria From The Opera Il Farnace Arranged For Voice And Piano D Minor Vivaldi Antonio Da Quel Ferro Aria From The Opera Il Farnace Arranged For Voice And Piano D Minor sheet music has been read 12115 times. -

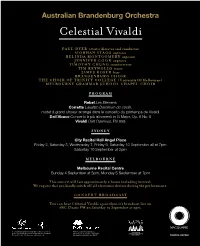

Celestial Vivaldi

Australian Brandenburg Orchestra Celestial Vivaldi PAUL DYER artistic director and conductor SIOBHAN STAGG soprano BELINDA MONTGOMERY soprano JENNIFER COOK soprano TIMOTHY CHUNG sountertenor TIM REYNOLds tenor JAMES ROSER bass BRANDENBURG CHOIR THE CHOIR OF TRINITY COLLEGE (University Of Melbourne) MELBOURNE GRAmmAR SCHOOL CHAPEL CHOIR P ROGRA M Rebel Les Elémens Corrette Laudate Dominum de coelis, motet à grand choeur arrangé dans le concerto du printemps de Vivaldi Dall’Abaco Concerto à più istrumenti in G Major, Op. 6 No. 5 Vivaldi Dixit Dominus, RV 595 S Y D NEY City Recital Hall Angel Place Friday 2, Saturday 3, Wednesday 7, Friday 9, Saturday 10 September all at 7pm Saturday 10 September at 2pm M ELBOURNE Melbourne Recital Centre Sunday 4 September at 5pm, Monday 5 September at 7pm This concert will last approximately 2 hours including interval. We request that you kindly switch off all electronic devices during the performance. C ON C ERT BROA DC A S T You can hear Celestial Vivaldi again when it's broadcast live on ABC Classic FM on Saturday 10 September at 2pm. The Australian Brandenburg Orchestra is assisted The Australian Brandenburg by the Australian Government through the Australia Orchestra is assisted by the NSW Council, its arts funding and advisory body. Government through Arts NSW. PRINCIPAL PARTNER Celestial Vivaldi At the beginning of the eighteenth century France was Europe’s super power, under the leadership of Rebel composed very little church music and only one opera, concentrating his efforts instead on songs, the charismatic and immensely powerful King Louis XIV. Calling himself the “Sun King”, giver of light, instrumental chamber works and, most successfully of all, dance music.