Harpur FINAL

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

China Report KYE.Qxp

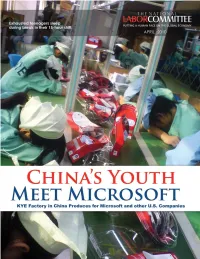

China’s Youth Meet Microsoft Acknowledgements: Report: Charles Kernaghan Photography: Anonymous Chinese workers Research Jonathann Giammarco Editing: Barbara Briggs Report design:Kenneth Carlisle Cover design Aaron Hudson Additional research was carried out by National Labor Committee interns: Margaret Martone Cassie Rusnak Clara Stuligross Elana Szymkowiak National Labor Committee 5 Gateway Center, 6th Floor Pittsburgh, PA 15222 Tel: 412-562-2406 www.nlcnet.org nlc @nlcnet.org China’s Youth Meet Microsoft Workers are paid 65 cents an hour, which falls to a take-home wage of 52 cents after deductions for factory food. China’s Youth Meet Microsoft Table of Contents Preface by an anonymous Chinese labor rights activist and scholar . .1 Executive Summary . .3 Introduction by Charles Kernaghan Young, Exhausted & Disponsible: Teenagers Producing for Microsoft . .4 Company Profile: KYE Systems Corp . .6 A Day in the Life of a young Microsoft worker . .7 Microsoft Workers’ Shift . .9 Military-like Discipline . .10 KYE Recruits up to 1,000 Teenaged “Work Study” Students . .14 Company Dorms . .16 Factory Cafeteria Food . .17 China’s Factory Workers Trapped with no Exit . .18 State and Corporate Factory Audits a Complete Failure . .19 Wages—below subsistence level . .21 Hours . .23 Is there a Union at the KYE factory? . .25 The Six S’s . .26 Postscript . .27 China’s Youth Meet Microsoft China’s Youth Meet Microsoft PREFACE by Anonymous Chinese labor rights activist and scholar “The idea that ‘without sweatshops workers would starve to death’ is a lie that corporate bosses use to cover their guilt.” China does not have unions in the real sense of the word. -

Global Village Or Global Pillage?

Darrell G. Moen, Ph.D. Promoting Social Justice, Human Rights, and Peace Global Village or Global Pillage? Narrated by Edward Asner (25 minutes: 1999) Transcribed by Darrell G. Moen The Race to the Bottom Narrator: The global economy: for those with wealth and power, it's meant big benefits. But what does the "global economy" mean for the rest of us? Are we destined to be its victims? Or can we shape its future - and our own? "Globalization." "The new world economy." Trendy terms. Whether we like it or not, the global economy now affects us: as consumers, as workers, as citizens, and as members of the human family. Janet Pratt used to work for the Westinghouse plant in Union City, Indiana. She found out how directly she could be affected by the global economy when the plant was closed and she lost her job. Her employer opened a new plant in Juarez, Mexico, and asked Janet to train the workers there. Janet Pratt (former Westinghouse employee) : At first I thought, "Are you crazy? Do you think I'm going to go down there and help you out [after you took my job away]?" I wanted to find out where my job was; where it had went. So that's why I decided to go. What I found there was a completely different world. You get into Juarez and [see] nothing but rundown shacks. And they were hard-working people. They were working, doing the same thing I had done up here [in Indiana]. But they were doing it for 85 cents an hour. -

Corporation Fonds

The Corporation fonds Compiled by Cobi Falconer (2005) and Tracey Krause (2005, 2006) University of British Columbia Archives Table of Contents Fonds Description o Title / Dates of Creation / Physical Description o Administrative History o Scope and Content o Notes Series Descriptions o Research o Correspondence o Pre-Production o Production . Transcriptions o Post-Production o Audio/Video tapes o Photographs File List Catalogue entry (UBC Library catalogue) Fonds Description The Corporation fonds. - 1994-2004. 2.03 m of textual material. 904 video cassette tapes. 10 audio cassette tapes. 12 photographs. Administrative History The Corporation, a film released in 2004, is a ground breaking movie documentary about the identity, economic, sociological, and environmental impact of the dominant and controversial institution of corporations. Based on the book The Corporation: The Pathological Pursuit of Profit and Power by Joel Bakan, the film portrays corporations as a legal person and how this status has contributed to their rise in dominance, power, and unprecedented wealth in Western society. The Corporation exposes the exploitation of corporations on democracy, the planet, the health of individuals which is carried out through case studies, anecdotes, and interviews. The documentary includes 40 interviews of CEOs, critics, whistle blowers, corporate spies, economists, and historians to further illuminate the "true" character of corporations. The Corporation was the conception of co-creator, Vancouver based, Mark Achbar; and co-creator, associate producer, and writer Joel Bakan. The film, coordinated by Achbar and Jennifer Abbott and edited by Abbott has currently received 26 international awards, and was awarded the winner of the 2004 Sundance Audience Award and Best Documentary at the 2005 Genie Awards. -

Charles Kernaghan Director, National Labor Committee

Charles Kernaghan Director, National Labor Committee HISTORY > Triangle Shirtwaste Fire If you go back to the Triangle Shirtwaste fire in 1911, that was an incredible shock to the country when 146 women were trapped, many of them leapt to their death, blood ran in the streets. But the interesting thing is, after the Triangle Shirtwaste fire on March 25, 1911, 100,000 people marched in the funeral procession. 400,000 people lined the streets. There was outrage. And the motto was, who is going to protect the working girl? Who is going to protect the working woman? We’ve lost that. And, in fact, sweatshops have come back. Sweatshops were wiped out of the United States in 1938. They are back now, with a vengeance. 65% of all apparel operations in New York City are sweatshops. 50,000 workers. 4,500 factories out of 7,000. And we’re talking about workers getting a dollar or two an hour. So it’s back and back with a vengeance because of the global economy. We’re talking about people working 100 hours a week. LABOUR > Worker Rights, Yeah Right Technically, the definition of a sweatshop is violation of wage and hour laws. But that doesn’t put the human face on it. So when you’re talking about sweatshops in a place like Bangladesh, for example, you’re talking about young women, 16 to 25 years of age, locked in factories behind barbed wire with armed guards. You’re talking about people working from 8:00 in the morning until 10:00 at night, 7 days a week, 30 days a month, for wages of about 8 to 18 cents an hour. -

Sandoval 2005 Contemporary Anti-Sweatshop Movement

10.1177/0730888405278990WORKArmbruster-Sandoval AND OCCUPATIONS / ANTI-SWEATSHOP / November 2005 MOVEMENT & SOCIAL JUSTICE Workers of the World Unite? The Contemporary Anti-Sweatshop Movement and the Struggle for Social Justice in the Americas RALPH ARMBRUSTER-SANDOVAL University of California, Santa Barbara The contemporary anti-sweatshop movement emerged more than 10 years ago. During that time period, numerous campaigns have challenged sweatshop labor practices (particularly in the garment industry) throughout the Americas. This article examines four such campaigns that pri- marily involved Central American garment workers and U.S.-based nongovernment organiza- tions. The results of these case studies were relatively mixed. Gains (better wages and working conditions) were usually not broadened or sustained over time. What factors explain these dispa- rate outcomes? Following and expanding on theoretical concepts and models embedded within the globalization and transnational social movement literatures, the author explores that ques- tion, describing each campaign’s dynamics and comparatively analyzing all four. The author concludes with some short-term, medium-term, and long-term proposals for addressing the vari- ous obstacles that the anti-sweatshop movement currently faces. Keywords: sweatshop; garment workers; Central America; cross-border labor; maquiladora orkers of the world unite” remains a potent and powerful rallying “Wcry, especially when one considers the globalization of the apparel industry and the miserable wages and working conditions that the world’s garment workers currently face (Ross, 2004). Transnational (or cross- border) labor solidarity could potentially mitigate the possibility and reality of capital mobility and thereby restrain the seemingly intractable, never- ending race to the bottom, but this is no simple task. -

Strategic Public Relations, Sweatshops, and the Making of a Global Movement by B.J

The Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public Policy Working Paper Series Strategic Public Relations, Sweatshops, and the Making of a Global Movement By B.J. Bullert Shorenstein Fellow, Fall 1999 University of Washington #2000-14 Copyright Ó 2000, President and Fellows of Harvard College All rights reserved When an estimated 40,0001 marched in Seattle to protest the World Trade Organization’s meeting, months of organizing by environmental groups, trade unions, human rights organizations and others, came to fruition. Organized publics in the form of trade unions, human rights groups and political elites succeeded in linking labor, environmental concerns and human rights to the WTO. The citizens who took to the street succeeded in drawing the attention of the reading and viewing public through the media to what they contend is the human and environmental costs of the "free trade" in the global economy. Although many reporters, especially television newsmen, were keen to capture the dramatic visuals of breaking glass, Darth Vader cops, and a youthful protestor running off with a Starbucks espresso machine, the overall impact of the protest shifted the media frame on the globalization debate in the press initially by expanding the coverage of genetic engineering and labor conditions in the developing economies.2 The environmental, human rights, labor rights and sweatshop issues culminating in the protests against WTO were years in the making, and strategic public relations professionals working with grass-roots organizations and NGOs were integral in shaping them. They publicized a vision of the global economy that countered one based on profits, market-share and high returns on financial investments for stockholders. -

The Student Anti-Sweatshop Campaign at Georgia State University

“Is GSU Apparel Made in Sweatshops?”: The Student Anti-Sweatshop Campaign at Georgia State University A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the College of Arts and Sciences Georgia State University 2002 by Takamitsu Ono Committee: ________________________________ Dr. Behrooz Ghamari-Tabrizi, Chair ________________________________ Dr. Charles L. Jaret, Member ________________________________ Dr. Ian C. Fletcher, Member _________________________________ Date __________________________________ Dr. Ronald C. Reitzes Department Chair 1 Table of Contents Introduction……………………………………………………………………………….4 A Methodological Consideration………………………………………………….8 Chapter 1 Globalization……………………………………………………………..11 Clarifying the Meanings of “Globalization”……………………………………..11 Cultural Globalization……………………………………………………14 Political Globalization…………………………………………………...18 Economic Globalization…………………………………………….……21 What Are “Sweatshops”?………………………………………………………..41 Accounting for the Emergence of Sweatshops…………………………..49 Resisting “Globalization from Above”………………………………………….58 The Global Anti-Corporate and Anti-Sweatshop Movements…………..60 Some Effects of the Anti-Sweatshop Movement………………………...67 Chapter 2 Students Organizing for Economic Justice in the 1990s and Beyond…...73 Growing U.S. Campus Activism for Economic Justice in the 1990s……………73 United Students Against Sweatshops (USAS)……………………………….…..75 Chapter 3 The Anti-Sweatshop Campaign at Georgia State University………..…..88 The Emergence of the Campaign………………………………………………...88 -

U.S.-Jordan Free Trade Agreement Descends Into Human Trafficking & Involuntary Servitude 540 West 48Th St., 3Rd Fl

U.S.-Jordan Free Trade Agreement Descends into Human Trafficking & Involuntary Servitude 540 West 48th St., 3rd Fl. New York, NY 10036 P: 212.242.3002 F: 212.242.3821 www.nlcnet.org Acknowledgments U.S. Jordan Free Trade Agreement Descends Into Human Trafficking & Involuntary Servitude. Tens of Thousands of Guest Workers Held in Involuntary Servitude May 2006 By Charles Kernaghan, National Labor Committee With research and production assistance from: Amanda Agro, Barbara Briggs, Christine Clarke, Matt D’Amico, Daniel De Bonis, Aysha Juthi, Amanda Teckman Design by Tomas Donoso We especially want to thank the over one hundred very brave guest workers in Jordan who told us their stories as well as the workers who were forcibly returned to Bangladesh. At grave risk to themselves, they gathered clothing labels and carried out research with the hope that their work would help improve conditions for the tens of thousands of guest workers in Jordan. We also want to thank our partners in Bangladesh, the Bangladesh Center for Workers’ Solidarity and the National Garment Workers Federation for their extraordinary leadership and assistance. Contents How the Work was Done 1 Al Shahaed Apparel & Textile: 3 Wal-Mart & K-Mart Western Factory: 11 Do Any of Us Really Want a “Bargain” Based on Trafficking of Young Women into Involuntary Servitude? Duty Free Access to the U.S. Market 19 Al Safa Garments: 20 Sewing Clothing for Gloria Vanderbilt, Mossimo & Kohl’s; Young Woman Raped - Hangs Herself Action Plan: 25 To Bring Supplier Plants in Compliance with Jordanian Law Recruitment Ad for Star Garments 26 Jordan’s Labor Law 27 Maintrend: 28 Human Trafficking & Involuntary Servitude. -

Overseas Sweatshop Abuses, Their Impact on U.S. Workers, and the Need for Anti–Sweatshop Legislation

S. HRG. 110–1062 OVERSEAS SWEATSHOP ABUSES, THEIR IMPACT ON U.S. WORKERS, AND THE NEED FOR ANTI–SWEATSHOP LEGISLATION HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON INTERSTATE COMMERCE, TRADE, AND TOURISM OF THE COMMITTEE ON COMMERCE, SCIENCE, AND TRANSPORTATION UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION FEBRUARY 14, 2007 Printed for the use of the Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 35–685 PDF WASHINGTON : 2010 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Nov 24 2008 15:17 Oct 01, 2010 Jkt 035685 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 S:\WPSHR\GPO\DOCS\35685.TXT SCOM1 PsN: JACKIE SENATE COMMITTEE ON COMMERCE, SCIENCE, AND TRANSPORTATION ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION DANIEL K. INOUYE, Hawaii, Chairman JOHN D. ROCKEFELLER IV, West Virginia TED STEVENS, Alaska, Vice Chairman JOHN F. KERRY, Massachusetts JOHN MCCAIN, Arizona BYRON L. DORGAN, North Dakota TRENT LOTT, Mississippi BARBARA BOXER, California KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas BILL NELSON, Florida OLYMPIA J. SNOWE, Maine MARIA CANTWELL, Washington GORDON H. SMITH, Oregon FRANK R. LAUTENBERG, New Jersey JOHN ENSIGN, Nevada MARK PRYOR, Arkansas JOHN E. SUNUNU, New Hampshire THOMAS R. CARPER, Delaware JIM DEMINT, South Carolina CLAIRE MCCASKILL, Missouri DAVID VITTER, Louisiana AMY KLOBUCHAR, Minnesota JOHN THUNE, South Dakota MARGARET L. CUMMISKY, Democratic Staff Director and Chief Counsel LILA HARPER HELMS, Democratic Deputy Staff Director and Policy Director MARGARET SPRING, Democratic General Counsel LISA J. -

Teaching About Sweatshops and the Global Economy

Teaching about Sweatshops and the Global Economy “How often do you see students protesting the exploitation of labor,” a friend and fellow political economist, asked me late one evening. “They deserve our support,” he insisted. Of course they do. That is why last Fall I taught “Sweatshops and the Global Economy,” a first year seminar at Wheaton College, a small New England liberal arts college, where I have worked for over two decades. But teaching a first year seminar about sweatshops was not always the act of solidarity I had imagined. In class, I found myself confronting many of the same arguments I had encountered writing a reply to the defenders of globalization and critics of the anti-sweatshop movement (Collins and Miller, 2000). That is hardly surprising. After all, every entering student at Wheaton is required to take a first year seminar. Engaging those students, not the group of sweatshop activists I had somehow convinced myself would be taking my course, was something I struggled with all semester. Those struggles are much of what I report on in my article. I developed techniques (exercises, arguments, and discussion strategies), and found materials (videos, pamphlets, personal testimonies) that worked -- engaged the students in a critical analysis of sweatshops, of the effects of globalization, and of the role of women in the world export factories. But many times my efforts fell short. I try to report honestly what I learned from those efforts as well. Inside Sweatshops and The Global Economy 2 “Sweatshops and the Global Economy” was one of eighteen sections of Wheaton’s seminar program for first year students. -

Working Women's Fights for Labor Rights

Annual Album Working Women’s Fights for Labor Rights — 1911 & 2011: Snapshots of the Past Year’s Local Labor Activities History Professor Stanislau Pugliese introduces new documentary on the Triangle tragedy. 2. “WHY OUR CLOTHES ARE STILL MADE IN SWEATSHOPS – AND WHAT TO DO ABOUT IT” was Hofstra's commemoration of the Triangle workers, held on campus March 24th (the day before the centennial). History Professor Stanislau Pugliese first introduced a moving PBS documentary film of the Triangle tragedy. Then the keynote speaker, Charles Kernaghan, director of the Institute for Global Labor and Human Rights (formerly the National Labor Committee) showed TV news footage (largely ignored by the US media) of a similar fatal high-rise factory fire just months before in December 2010. At the Hameem factory in Savar, Bangladesh, where a mostly young female workforce sews garments for The Gap, 29 workers died (some jumping in terror from upper windows) and over 100 were injured after being trapped in workrooms reportedly locked by the owners. Most workers at the factory worked 80 hours per week and made only 28 cents an hour – just one tenth as much (in 2010 US dollars) as Charles Kernaghan the Triangle workers did in 1911. Mr. Kernaghan discussed how American fashion companies have slashed American jobs and labor costs by shifting nearly all of our clothing production overseas. He spoke in favor of a bipartisan bill before Congress, the Decent Working Conditions and Fair Competition Act, aimed at prohibiting the import, export, and sale of goods made with sweatshop labor. This event was organized 1. -

Download Robert-J.S.-Ross-Ross.Twilight.Chapterfour..Pdf, 311 KB

Copyright © Cornell University 4 THE TWILIGHT OF CSR Life and Death Illuminated by Fire Robert J. S. Ross In the years since the Interfaith Center on Corporate Responsibility (ICCR) was founded (1971–1973, see ICCR 2011) most of the corporate world has adopted nominal policies that project individual firms as ethical citizens, compliant with environmental and social standards and concerned about the well-being of employees—including those it indirectly engages through contracting arrange- ments. Corporate codes of conduct have become common and multiparty codes are proliferating. This is especially so in the global apparel business, where sweat- shop, child labor, and forced labor abuses have proved extremely embarrassing and potentially harmful to reputation-sensitive brands and retailers (Esbenshade 2012 and in chapter 3 of this volume; Anner, Bair, and Blasi 2012). This paper places the issue of labor standards in the strategic context of a global “race to the bottom” in the apparel business, using US trade data as evidence for worldwide cheapening of garments and the labor of the people who make them. In this context, researchers concerned about global labor standards and the activist antisweatshop movements have been skeptical about voluntary codes of conduct and self-policing, internally held social compliance audits. This paper examines factory fires and building collapses in Bangladesh as a serial case study in CSR efficacy. It uses quantitative data jointly developed by the author and staff members of the International Labor Rights Forum and the Clean Clothes Cam- paign and briefly reported in the ILRF document “Deadly Secrets.” From that data are gleaned six high-mortality incidents for further study.