The Sale of Children for Labor Exploitation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

China Report KYE.Qxp

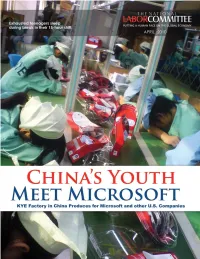

China’s Youth Meet Microsoft Acknowledgements: Report: Charles Kernaghan Photography: Anonymous Chinese workers Research Jonathann Giammarco Editing: Barbara Briggs Report design:Kenneth Carlisle Cover design Aaron Hudson Additional research was carried out by National Labor Committee interns: Margaret Martone Cassie Rusnak Clara Stuligross Elana Szymkowiak National Labor Committee 5 Gateway Center, 6th Floor Pittsburgh, PA 15222 Tel: 412-562-2406 www.nlcnet.org nlc @nlcnet.org China’s Youth Meet Microsoft Workers are paid 65 cents an hour, which falls to a take-home wage of 52 cents after deductions for factory food. China’s Youth Meet Microsoft Table of Contents Preface by an anonymous Chinese labor rights activist and scholar . .1 Executive Summary . .3 Introduction by Charles Kernaghan Young, Exhausted & Disponsible: Teenagers Producing for Microsoft . .4 Company Profile: KYE Systems Corp . .6 A Day in the Life of a young Microsoft worker . .7 Microsoft Workers’ Shift . .9 Military-like Discipline . .10 KYE Recruits up to 1,000 Teenaged “Work Study” Students . .14 Company Dorms . .16 Factory Cafeteria Food . .17 China’s Factory Workers Trapped with no Exit . .18 State and Corporate Factory Audits a Complete Failure . .19 Wages—below subsistence level . .21 Hours . .23 Is there a Union at the KYE factory? . .25 The Six S’s . .26 Postscript . .27 China’s Youth Meet Microsoft China’s Youth Meet Microsoft PREFACE by Anonymous Chinese labor rights activist and scholar “The idea that ‘without sweatshops workers would starve to death’ is a lie that corporate bosses use to cover their guilt.” China does not have unions in the real sense of the word. -

The Determinants of Child Labor: Theory and Evidence

RESEARCH SEMINAR IN INTERNATIONAL ECONOMICS School of Public Policy The University of Michigan Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109-1220 Discussion Paper No. 486 The Determinants of Child Labor: Theory and Evidence Drusilla K. Brown Tufts University Alan V. Deardorff and Robert M. Stern University of Michigan September, 2002 Recent RSIE Discussion Papers are available on the World Wide Web at: http://www.spp.umich.edu/rsie/workingpapers/wp.html 2 THE DETERMINANTS OF CHILD LABOR: THEORY AND EVIDENCE By Drusilla K. Brown Tufts University Alan V. Deardorff University of Michigan and Robert M. Stern University of Michigan September 2002 I. Introduction The specter of small children toiling long hours under dehumanizing conditions has precipitated an intense debate concerning child labor over the past decade and a half. As during the midst of the 19th century industrial revolution, policymakers and the public have attempted to come to grips with the causes and consequences of child labor. Coordinating a policy response has revealed the complexity and moral ambiguity of the phenomenon of working children. Although child labor has been the norm throughout history, the fact of children working and the difficult conditions under which children work occasionally become more evident. In the midst of the 19th century, child labor became more visible because children were drawn into an industrial setting. Currently, child labor has become more visible because of the increase in the number of children producing goods for export. Our purpose here is not to provide a definitive diagnosis of the causes and consequences of child labor, but rather to review the existing theoretical, empirical, and historical literature as to why and when children work. -

The Open Court

— 3^0 The Open Court. DEVOTED TO THE RELIGION OF SCIENCE. Two Dollars per Year. No. 287. (Vol. VII.— 8.) CHICAGO, ) FEBRUARY 23, 1893. '( Single Copies, 5 Cents. Copyright by The Open Court Publishing Co.—Reprints are permitted only on condition of giving full credit to Author and Publisher. than by daily massacres. AUTOS-DA-FK. They also believed in the necessity of popular pastimes, and realised the wisdom BY DR. FELIX L. 0SW.4LD. of propitiating the leaders of victorious armies, and Moral philosophers have often expressed the opin- under the best as well as under the worst of the twenty- ion that no change in the by-laws of ethics will ever six world-kings the significance of the vce victis was affect the stability of certain conventional maxims brought home to vanquished foes and captured crimi- not strictly compatible, in all cases, with our present nals in those orgies of bloodshed which have been conceptions of ideal justice. Among the numerous called the "foulest stain on the records of the human proofs demonstrating the permanence of those inter- race." national compromise axioms we might mention the Yet among the Roman writers who utterly failed to facts that Might has always biased the standards of anticipate that verdict of posterity, there were some Right, and that no protest against the atrocity of in- exemplars of Stoic ethics, and some who frequently dividual sufferings has ever been permitted to inter- denounced acts of wanton cruelty to animals and men. fere with the promotion of principles supposed to in- Cicero, who treated his slaves more kindly than our volve the supreme welfare of the community. -

The Tragedy of Hamlet

THE TRAGEDY OF HAMLET THE WORKS OF SHAKESPEARE THE TRAGEDY OF HAMLET EDITED BY EDWARD DOWDEN n METHUEN AND CO. 36 ESSEX STREET: STRAND LONDON 1899 9 5 7 7 95 —— CONTENTS PAGE Introduction ix The Tragedy of Hamlet i Appendix I. The "Travelling" of the Players. 229 Appendix II.— Some Passages from the Quarto of 1603 231 Appendix III. Addenda 235 INTRODUCTION This edition of Hamlet aims in the first place at giving a trustworthy text. Secondly, it attempts to exhibit the variations from that text which are found in the primary sources—the Quarto of 1604 and the Folio of 1623 — in so far as those variations are of importance towards the ascertainment of the text. Every variation is not recorded, but I have chosen to err on the side of excess rather than on that of defect. Readings from the Quarto of 1603 are occa- sionally given, and also from the later Quartos and Folios, but to record such readings is not a part of the design of this edition. 1 The letter Q means Quarto 604 ; F means Folio 1623. The dates of the later Quartos are as follows: —Q 3, 1605 161 1 undated 6, For ; Q 4, ; Q 5, ; Q 1637. my few references to these later Quartos I have trusted the Cambridge Shakespeare and Furness's edition of Hamlet. Thirdly, it gives explanatory notes. Here it is inevitable that my task should in the main be that of selection and condensation. But, gleaning after the gleaners, I have perhaps brought together a slender sheaf. -

The Ilo's Shifts in Child Labour Policy: Regulation and Abolition

Chapter 7 The ilo’s Shifts in Child Labour Policy: Regulation and Abolition Edward van Daalen and Karl Hanson Abstract After wwii the International Labour Organization (ilo) slowly but surely developed a ‘two plank’ approach to child labour, aimed at harmonising the need to protect chil- dren who do work, with the long-term goal of abolishing all forms of child labour. Dur- ing the 1990s the ‘two plank’ approach, which included the regulation and humanisa- tion of children’s work, gradually evolved into a more singular approach aimed only at the full eradication of all child labour, starting with the ‘worst forms’. Based on an anal- ysis of the relevant legal and policy documents produced by the ilo and other inter- national Organizations, completed with in-depth interviews with key informants, we examine the internal and external developments that made the ‘abolitionist’ approach now the only perspective that shapes the ilo’s child labour policies. We conclude that, after a century of ilo child labour policy, the intermediate objective of improving chil- dren’s working conditions is now just as relevant as it was before the turn away from the ‘two plank’ approach. For the ilo to shift its position at this time, it needs to reach out to the research community, international development actors as well as local gov- ernments and social movements to develop locally relevant, evidence-based policies for dealing with the diversity of children’s work in the world’s fast changing formal and informal economies. 1 Introduction The abolition of child labour has been one of the principle objectives of the International Labour Organization (ilo) ever since its inception in 1919. -

Chapter Iii Children; Easy to Target

CHAPTER III CHILDREN; EASY TO TARGET CHILD TRAFFICKING III CHAPTER 3 CHILDREN;139 EASY TO TARGET Globally, one in every three victims detected is a child. FIG. 49 Shares of detected victims of traf- Patterns about the age profile of the victims, however, ap- ficking, by age group and national pear to change drastically across different regions. Coun- income,* 2018 (or most recent) tries in West Africa, South Asia and Central America and 100% the Caribbean typically present a much higher share of 90% children among total victims detected. 80% More broadly, differences in the age composition of de- 50 70% tected victims appear to be related to the income level of 67 63 60% the country of detection. The detection of children ac- 86 count for a significantly higher proportion in low income 50% countries when compared to high income countries. As 40% such, wealthier countries tend to detect more adults than 30% children among the trafficking victims. 50 20% These differences could be the result of varying criminal 33 37 justice focuses in different parts of the world. At the same 10% 14 time, however, they may reflect different trafficking pat- 0% terns according to countries’ socio-economic conditions. High Upper Lower Low Income Income Middle Middle Countries Countries Income Income This chapter provides an overview of the dynamics relat- Countries Countries ed to the trafficking of children. The first section discuss- es the main forms of child trafficking, namely trafficking Share of adult victims detected (18 years old or above) for forced labour and trafficking for sexual exploitation. -

The Child's Right to Participation – Reality Or Rhetoric? 301 Pp

The Child’s Right to Participation – Reality or Rhetoric? The Child’s Right to Participation – Reality or Rhetoric? Rebecca Stern Dissertation presented at Uppsala University to be publicly examined in Grotiussalen, Uppsala, Friday, September 22, 2006 at 10:15 for the degree of Doctor of Laws. The examination will be conducted in English. Abstract Stern, R. 2006. The Child's Right to Participation – Reality or Rhetoric? 301 pp. Uppsala. ISBN 91-506-1891-1. This dissertation examines the child’s right to participation in theory and practice within the context of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child and other international human rights instruments. Article 12 of the Convention establishes the right of the child to express views and to have those views respected and properly taken into consideration. The emphasis of the study is on the democracy aspects of child participation and on how the implementation of the right to participation could become more effective. For these purposes, the theoretical underpinnings of the child’s right to participation are examined with a particular focus on the impact of power structures. In order to clarify how state parties to the Convention have implemented article 12 and the way they argue regarding possible obstacles for implementation, jurisprudence and case law (practice) of the Committee on the Rights of the Child, as well as supervisory bodies of other international human rights instruments, are studied. In particular, the importance of traditional attitudes towards children on the realisation of participation rights for children is analysed. The case of India is presented as an example of how a state party to the Convention can argue on this matter. -

The Barefoot Lawyers: Prosecuting Child Labour in the Supreme Court of India

THE BAREFOOT LAWYERS: PROSECUTING CHILD LABOUR IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA Ranjan K. Agarwal* I. INTRODUCTION On the eve of India’s independence from British rule, India’s first Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, issued a challenge to the constituent assembly: “We end today a period of ill fortune and India discovers herself again. The achievement we celebrate today is but a step, an opening of opportunity, to the greater triumphs and achievements that await us. Are we brave enough and wise enough to grasp this opportunity and accept the challenge of the future?”1 For the most part, this challenge has gone unmet in the fifty-seven years since India’s independence. In 1999, twenty-six percent of Indians lived below the poverty line; sixteen percent of the population was officially “destitute” in 1998.2 As of 1997, India’s literacy rate was fifty-two percent, amongst the lowest in the world.3 Indians respond that their country is the largest democracy in the world, and one of the few democracies in Asia. In the face of economic hardship, communal and religious strife, the horrors of partition and the legacy of colonialism, India has remained a democratic country. Even then, democracy has not achieved for India the position of influence in the world and the more widely shared prosperity that its citizens hoped for their country. Too many Indians are poor, hungry, illiterate and view their government with contempt. For example, Indian newspapers estimate that hundreds of suspected criminals stood for election in the 1997 municipal votes in Delhi and Mumbai.4 Transparency International, a German anti-corruption organization, ranks India amongst the most corrupt * B.A. -

The Best Interests of the Child in Cases of Migration Kalverboer, Margrite; Beltman, Daan; Van Os, Carla; Zijlstra, Elianne

University of Groningen The best interests of the child in cases of migration Kalverboer, Margrite; Beltman, Daan; van Os, Carla; Zijlstra, Elianne Published in: International Journal of Children's Rights DOI: 10.1163/15718182-02501005 IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2017 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Kalverboer, M., Beltman, D., van Os, C., & Zijlstra, E. (2017). The best interests of the child in cases of migration: Assessing and determining the best interests of the child in migration procedures. International Journal of Children's Rights, 25(1), 114-139. https://doi.org/10.1163/15718182-02501005 Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). The publication may also be distributed here under the terms of Article 25fa of the Dutch Copyright Act, indicated by the “Taverne” license. More information can be found on the University of Groningen website: https://www.rug.nl/library/open-access/self-archiving-pure/taverne- amendment. Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

Global Village Or Global Pillage?

Darrell G. Moen, Ph.D. Promoting Social Justice, Human Rights, and Peace Global Village or Global Pillage? Narrated by Edward Asner (25 minutes: 1999) Transcribed by Darrell G. Moen The Race to the Bottom Narrator: The global economy: for those with wealth and power, it's meant big benefits. But what does the "global economy" mean for the rest of us? Are we destined to be its victims? Or can we shape its future - and our own? "Globalization." "The new world economy." Trendy terms. Whether we like it or not, the global economy now affects us: as consumers, as workers, as citizens, and as members of the human family. Janet Pratt used to work for the Westinghouse plant in Union City, Indiana. She found out how directly she could be affected by the global economy when the plant was closed and she lost her job. Her employer opened a new plant in Juarez, Mexico, and asked Janet to train the workers there. Janet Pratt (former Westinghouse employee) : At first I thought, "Are you crazy? Do you think I'm going to go down there and help you out [after you took my job away]?" I wanted to find out where my job was; where it had went. So that's why I decided to go. What I found there was a completely different world. You get into Juarez and [see] nothing but rundown shacks. And they were hard-working people. They were working, doing the same thing I had done up here [in Indiana]. But they were doing it for 85 cents an hour. -

In Search of the Amazon: Brazil, the United States, and the Nature of A

IN SEARCH OF THE AMAZON AMERICAN ENCOUNTERS/GLOBAL INTERACTIONS A series edited by Gilbert M. Joseph and Emily S. Rosenberg This series aims to stimulate critical perspectives and fresh interpretive frameworks for scholarship on the history of the imposing global pres- ence of the United States. Its primary concerns include the deployment and contestation of power, the construction and deconstruction of cul- tural and political borders, the fluid meanings of intercultural encoun- ters, and the complex interplay between the global and the local. American Encounters seeks to strengthen dialogue and collaboration between histo- rians of U.S. international relations and area studies specialists. The series encourages scholarship based on multiarchival historical research. At the same time, it supports a recognition of the represen- tational character of all stories about the past and promotes critical in- quiry into issues of subjectivity and narrative. In the process, American Encounters strives to understand the context in which meanings related to nations, cultures, and political economy are continually produced, chal- lenged, and reshaped. IN SEARCH OF THE AMAzon BRAZIL, THE UNITED STATES, AND THE NATURE OF A REGION SETH GARFIELD Duke University Press Durham and London 2013 © 2013 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ♾ Designed by Heather Hensley Typeset in Scala by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in - Publication Data Garfield, Seth. In search of the Amazon : Brazil, the United States, and the nature of a region / Seth Garfield. pages cm—(American encounters/global interactions) Includes bibliographical references and index. -

Alien Love- Passing, Race, and the Ethics of the Neighbor in Postwar

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Alien Love: Passing, Race, and the Ethics of the Neighbor in Postwar African American Novels, 1945-1956 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy In English By Hannah Wonkyung Nahm 2021 © Copyright by Hannah Wonkyung Nahm 2021 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Alien Love: Passing, Race, and the Ethics of the Neighbor in Postwar African American Novels, 1945-1956 by Hannah Wonkyung Nahm Doctor of Philosophy in English University of California, Los Angeles, 2021 Professor King-Kok Cheung, Co-Chair Professor Richard Yarborough, Co-Chair This dissertation examines Black-authored novels featuring White (or White-passing) protagonists in the post-World War II decade (1945-1956). Published during the fraught postwar political climate of agitation for integration and the continual systematic racism, many novels by Black authors addressed the urgent topic of interracial relationality, probing the tabooed question of whether Black and White can abide in love and kinship. One of the prominent—and controversial—literary strategies sundry Black novelists used in this decade was casting seemingly raceless or ambiguously-raced characters. Collectively, these novels generated a mixture of critical approval and dismissal in their time and up until recently, marginalized from the African American literary tradition. Even more critically overlooked than the ostensibly raceless project was the strategic mobilization of the trope of passing by some midcentury Black ii writers to imagine the racial divide and possible reconciliation. This dissertation intersects passing with postwar Black fiction that features either racially-anomalous or biracial central characters. Examining three novels from this historical period as my case studies, I argue that one of the ways in which Black writers of this decade have imagined the possibility of interracial love—with all its political pitfalls and ethical imperatives —is through the trope of passing.