Vigilantes and Verifiers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

China Report KYE.Qxp

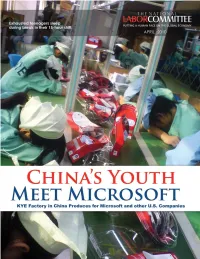

China’s Youth Meet Microsoft Acknowledgements: Report: Charles Kernaghan Photography: Anonymous Chinese workers Research Jonathann Giammarco Editing: Barbara Briggs Report design:Kenneth Carlisle Cover design Aaron Hudson Additional research was carried out by National Labor Committee interns: Margaret Martone Cassie Rusnak Clara Stuligross Elana Szymkowiak National Labor Committee 5 Gateway Center, 6th Floor Pittsburgh, PA 15222 Tel: 412-562-2406 www.nlcnet.org nlc @nlcnet.org China’s Youth Meet Microsoft Workers are paid 65 cents an hour, which falls to a take-home wage of 52 cents after deductions for factory food. China’s Youth Meet Microsoft Table of Contents Preface by an anonymous Chinese labor rights activist and scholar . .1 Executive Summary . .3 Introduction by Charles Kernaghan Young, Exhausted & Disponsible: Teenagers Producing for Microsoft . .4 Company Profile: KYE Systems Corp . .6 A Day in the Life of a young Microsoft worker . .7 Microsoft Workers’ Shift . .9 Military-like Discipline . .10 KYE Recruits up to 1,000 Teenaged “Work Study” Students . .14 Company Dorms . .16 Factory Cafeteria Food . .17 China’s Factory Workers Trapped with no Exit . .18 State and Corporate Factory Audits a Complete Failure . .19 Wages—below subsistence level . .21 Hours . .23 Is there a Union at the KYE factory? . .25 The Six S’s . .26 Postscript . .27 China’s Youth Meet Microsoft China’s Youth Meet Microsoft PREFACE by Anonymous Chinese labor rights activist and scholar “The idea that ‘without sweatshops workers would starve to death’ is a lie that corporate bosses use to cover their guilt.” China does not have unions in the real sense of the word. -

Corporate America, the Sullivan Principles, and the Anti-Apartheid Struggle

Black Power in the Boardroom: Corporate America, the Sullivan Principles, and the Anti-Apartheid Struggle JESSICA ANN LEVY This article traces the history of General Motors’ first black director, Leon Sullivan, and his involvement with the Sullivan Principles, a corporate code of conduct for U.S. companies doing business in Apartheid South Africa. Building on and furthering the postwar civil rights and anti-colonial struggles, the international anti-apartheid movement brought together students, union workers, and religious leaders in an effort to draw attention to the horrors of Apartheid in South Africa. Whereas many left-leaning activists advocated sanctions and divestment, others, Sullivan among them, helped lead the way in drafting an alternative strategy for American business, one focused on corporate-sponsored black empowerment. Moving beyond both narrow criticisms of Sullivan as a “sellout” and corporate propaganda touting the benefits of the Sullivan Prin- ciples, this work draws on corporate and “movement” records to reveal the complex negotiations between white and black executives as they worked to situate themselves in relation to anti-racist movements in the Unites States and South Africa. In doing so, it furthermore reveals the links between modern corporate social responsibility and the fight for Black Power within the corporation. © The Author 2019. Published by Cambridge University Press on behalf of the Business History Conference. doi:10.1017/eso.2019.32 Published online August 2, 2019 JESSICA ANN LEVY is a postdoctoral research associate in the Department of History and the Corruption Laboratory for Ethics, Accountability, and the Rule of Law (CLEAR) at the University of Virginia. -

Supply Chain Operations Audit

Building 243 University Campus Cranfield Bedford MK43 0AL Tel: +44 (0)1234 750323 Fax: +44 (0)1234 752040 www.scp-uk.co.uk Supply Chain Operations Audit by Dr. David Lascelles, Supply Chain Planning UK Limited High Impact Supply Chains Supply chain excellence has a real impact on business strategy. Supply chain management is a high impact mission that goes to the roots of a company’s very competitiveness. High-impact supply chains win market share and customer loyalty, create shareholder value, extend the strategic capability and reach of the business. Independent research shows that excellent supply chain management can yield: · 25-50% reduction in total supply chain costs · 25-60% reduction in inventory holding · 25-80% increase in forecast accuracy · 30-50% improvement in order-fulfilment cycle time · 20% increase in after-tax free cash flows That’s what we mean by high-impact. Does a high-impact supply chain leverage your business enterprise? Five Critical Success Factors Building a high-impact supply chain represents one of the most exciting opportunities to create value – and one of the most challenging. The key to success lies in knowing which levers to pull. Our research, together with practical experience, reveals that high-impact supply chains are, essentially, a function of five critical success factors: 1. A clear strategy: for the entire supply chain, tuned to market opportunities and focussed on customer service needs. 2. An integrated organisation structure: enabling the supply chain to operate as a single synchronised entity. 3. Excellent processes: for implementing the strategy, embracing all plan- source-make-deliver operations. -

SA 8000:2014 Documents with Manual, Procedures, Audit Checklist

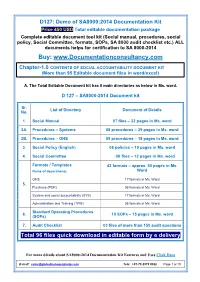

D127: Demo of SA8000:2014 Documentation Kit Price 450 USD Total editable documentation package Complete editable document tool kit (Social manual, procedures, social policy, Social Committee, formats, SOPs, SA 8000 audit checklist etc.) ALL documents helps for certification to SA 8000-2014 Buy: www.Documentationconsultancy.com Chapter-1.0 CONTENTS OF SOCIAL ACCOUNTABILITY DOCUMENT KIT (More than 95 Editable document files in word/excel) A. The Total Editable Document kit has 8 main directories as below in Ms. word. D 127 – SA8000-2014 Document kit Sr. List of Directory Document of Details No. 1. Social Manual 07 files – 22 pages in Ms. word 2A. Procedures – Systems 08 procedures – 29 pages in Ms. word 2B. Procedures – OHS 09 procedures – 18 pages in Ms. word 3. Social Policy (English) 08 policies – 10 pages in Ms. word 4. Social Committee 08 files – 12 pages in Ms. word Formats / Templates 43 formats – approx. 50 pages in Ms. Name of departments Word OHS 17 formats in Ms. Word 5. Purchase (PUR) 05 formats in Ms. Word System and social accountability (SYS) 17 formats in Ms. Word Administration and Training (TRG) 05 formats in Ms. Word Standard Operating Procedures 6. 10 SOPs – 15 pages in Ms. word (SOPs) 7. Audit Checklist 03 files of more than 150 audit questions Total 96 files quick download in editable form by e delivery For more détails about SA8000:2014 Documentation Kit Features and Uses Click Here E-mail: [email protected] Tele: +91-79-2979 5322 Page 1 of 10 D127: Demo of SA8000:2014 Documentation Kit Price 450 USD Total editable documentation package Complete editable document tool kit (Social manual, procedures, social policy, Social Committee, formats, SOPs, SA 8000 audit checklist etc.) ALL documents helps for certification to SA 8000-2014 Buy: www.Documentationconsultancy.com Part: B. -

Guide to Inspections of Quality Systems

FOOD AND DRUG ADMINISTRATION GUIDE TO INSPECTIONS OF QUALITY SYSTEMS 1 August 19991 2 Guide to Inspections of Quality Systems This document was developed by the Quality System Inspec- tions Reengineering Team Members Office of Regulatory Affairs Rob Ruff Georgia Layloff Denise Dion Norm Wong Center for Devices and Radiological Health Tim Wells – Team Leader Chris Nelson Cory Tylka Advisors Chet Reynolds Kim Trautman Allen Wynn Designed and Produced by Malaka C. Desroches 3 Foreword This document provides guidance to the FDA field staff on a new inspectional process that may be used to assess a medical device manufacturer’s compliance with the Quality System Regulation and related regulations. The new inspectional process is known as the “Quality System Inspection Technique” or “QSIT”. Field investigators may conduct an ef- ficient and effective comprehensive inspection using this guidance material which will help them focus on key elements of a firm’s quality system. Note: This manual is reference material for investi- gators and other FDA personnel. The document does not bind FDA and does not confer any rights, privi- leges, benefits or immunities4 for or on any person(s). Table of Contents Performing Subsystem Inspections. 7 Pre-announced Inspections. ..13 Getting Started. .15 Management Controls. .17 Inspectional Objectives 18 Decision Flow Chart 19 Narrative 20 Design Controls. .31 Inspectional Objectives 32 Decision Flow Chart 33 Narrative 34 Corrective and Preventive Actions (CAPA). .47 Inspectional Objectives 48 Decision Flow Chart 49 Narrative 50 Medical Device Reporting 61 Inspectional Objectives 62 Decision Flow Chart 63 Narrative 64 Corrections & Removals 67 Inspectional Objectives 68 Decision Flow Chart 69 Narrative 70 Medical Device Tracking 73 Inspectional Objectives 74 Decision Flow Chart 75 Narrative 76 Production and Process Controls (P&PC). -

Social Accounting: a Practical Guide for Small-Scale Community Organisations

Social Accounting: A Practical Guide for Small-Scale Community Organisations Social Accounting: A Practical Guide for Small Community Organisations and Enterprises Jenny Cameron Carly Gardner Jessica Veenhuyzen Centre for Urban and Regional Studies, The University of Newcastle, Australia. Version 2, July 2010 This page is intentionally blank for double-sided printing. Table of Contents INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………………………..1 How this Guide Came About……………………………………………………2 WHAT IS SOCIAL ACCOUNTING?………………………………………………..3 Benefits.………………………………………………………………………....3 Challenges.……………………………………………………………………....4 THE STEPS………………………………………...…………………………………..5 Step 1: Scoping………………………………….………………………………6 Step 2: Accounting………………………………………………………………7 Step 3: Reporting and Responding…………………….……………………….14 APPLICATION I: THE BEANSTALK ORGANIC FOOD…………………….…16 APPLICATION II: FIG TREE COMMUNITY GARDEN…………………….…24 REFERENCES AND RESOURCES…………………………………...……………33 Acknowledgements We would like to thank The Beanstalk Organic Food and Fig Tree Community Garden for being such willing participants in this project. We particularly acknowledge the invaluable contribution of Rhyall Gordon and Katrina Hartwig from Beanstalk, and Craig Manhood and Bill Roberston from Fig Tree. Thanks also to Jo Barraket from the The Australian Centre of Philanthropy and Nonprofit Studies, Queensland University of Technology, and Gianni Zappalà and Lisa Waldron from the Westpac Foundation for their encouragement and for providing an opportunity for Jenny and Rhyall to present a draft version at the joint QUT and Westpac Foundation Social Evaluation Workshop in June 2010. Thanks to the participants for their feedback. Finally, thanks to John Pearce for introducing us to Social Accounting and Audit, and for providing encouragement and feedback on a draft version. While we have adopted the framework and approach to suit the context of small and primarily volunteer-based community organisations and enterprises, we hope that we have remained true to the intentions of Social Accounting and Audit. -

Suggestions from Social Accountability International

Suggestions from Social Accountability International (SAI) on the work agenda of the UN Working Group on Human Rights and Transnational Corporations and Other Business Enterprises Social Accountability International (SAI) is a non-governmental, international, multi-stakeholder organization dedicated to improving workplaces and communities by developing and implementing socially responsible standards. SAI recognizes the value of the UN Working Group’s mandate to promote respect for human rights by business of all sizes, as the implementation of core labour standards in company supply chains is central to SAI’s own work. SAI notes that the UN Working Group emphasizes in its invitation for proposals from relevant actors and stakeholders, the importance it places not only on promoting the Guiding Principles but also and especially on their effective implementation….resulting in improved outcomes . SAI would support this as key and, therefore, has teamed up with the Netherlands-based ICCO (Interchurch Organization for Development) to produce a Handbook on How To Respect Human Rights in the International Supply Chain to assist leading companies in the practical implementation of the Ruggie recommendations. SAI will also be offering classes and training to support use of the Handbook. SAI will target the Handbook not just at companies based in Western economies but also at those in emerging countries such as Brazil and India that have a growing influence on the world’s economy and whose burgeoning base of small and medium companies are moving forward in both readiness, capacity and interest in managing their impact on human rights. SAI has long term relationships working with businesses in India and Brazil, where national companies have earned SA8000 certification and where training has been provided on implementing human rights at work to numerous businesses of all sizes. -

Chemical Management Audit Certification Supplier Management Verification Solutions

CHEMICAL MANAGEMENT AUDIT CERTIFICATION SUPPLIER MANAGEMENT VERIFICATION SOLUTIONS Intertek’s Chemical Management Audit solution is designed to help retailers and brands verify the safe handling and proper disposal of chemicals, in order to promote chemical management best practices throughout the global supply chain network. Your challenges, our solutions • Improved chemical management system unique techniques to best drive improvement Intertek’s Chemical Management Audit and practice through reduced environmental footprint, solution can help ensure effective chemical • Benchmarked results with global visibility increased efficiency and cost savings. management across your supply chain. The • Management transparency to enable This Chemical Management Audit is offered as process starts with an application of chemical targeted efforts. part of Intertek’s Supply Chain Solutions which expertise to provide a facility baseline risk help organizations all over the world manage • Identification of process efficiency and cost indicator, from which auditing of your facility compliance, risk, sustainability, and quality in savings can be efficiently planned. the supply chain. Intertek’s web-based platform and software • Assistance with green product design and helps ensure our Chemical Management certification Audit approach is the ideal tool for • Protect reputation risk, people and evaluating, tracking and monitoring chemical environment management performance in factories, Upon satisfactory completion of the chemical FOR MORE INFORMATION ultimately assuring overall performance management assessment and performance improvements. criteria, the manufacturer will receive a Intertek’s Chemical Management Audit report which details performance as well UK +44 116 296 1620 solution includes modular guidance for: as benchmarked comparisons with peers. The report showcases commitments of • Chemical Supply & Policy AMER +1 800 810 1195 moving towards zero discharge of hazardous • Management Practices chemicals. -

Regulating Corporations

PROVISIONAL EDITION Regulating Corporations A Resource Guide Désirée Abrahams* Geneva • December 2004 * Désirée Abrahams prepared this report during 2003 and early 2004, when she was a Research Assistant at the United Nations Research Institute for Social Development (UNRISD) in Geneva, Switzerland. The author would like to thank Peter Utting, Kate Ives and Anita Tombez for their research and editorial support. The report was prepared under the UNRISD project “Promoting Corporate Social and Environmental Responsibility in Developing Countries: The Potential and Limits of Voluntary Initiatives”, which is partly funded by the MacArthur Foundation. This edition may be subject to minor modifications and copy-editing prior to formal publication. The United Nations Research Institute for Social Development (UNRISD) is an autonomous agency engaging in multidisciplinary research on the social dimensions of contemporary problems affecting development. Its work is guided by the conviction that, for effective development policies to be formulated, an understanding of the social and political context is crucial. The Institute attempts to provide governments, development agencies, grassroots organizations and scholars with a better understanding of how development policies and processes of economic, social and environmental change affect different social groups. Working through an extensive network of national research centres, UNRISD aims to promote original research and strengthen research capacity in developing countries. Current research programmes include: Civil Society and Social Movements; Democracy, Governance and Human Rights; Identities, Conflict and Cohesion; Social Policy and Development; and Technology, Business and Society. A list of the Institute’s free and priced publications can be obtained by contacting: UNRISD Reference Centre Palais des Nations 1211 Geneva 10 Switzerland Tel +41 (0)22 917 3020 Fax +41 (0)22 917 0650 [email protected] www.unrisd.org Copyright © United Nations Research Institute for Social Development. -

Global Village Or Global Pillage?

Darrell G. Moen, Ph.D. Promoting Social Justice, Human Rights, and Peace Global Village or Global Pillage? Narrated by Edward Asner (25 minutes: 1999) Transcribed by Darrell G. Moen The Race to the Bottom Narrator: The global economy: for those with wealth and power, it's meant big benefits. But what does the "global economy" mean for the rest of us? Are we destined to be its victims? Or can we shape its future - and our own? "Globalization." "The new world economy." Trendy terms. Whether we like it or not, the global economy now affects us: as consumers, as workers, as citizens, and as members of the human family. Janet Pratt used to work for the Westinghouse plant in Union City, Indiana. She found out how directly she could be affected by the global economy when the plant was closed and she lost her job. Her employer opened a new plant in Juarez, Mexico, and asked Janet to train the workers there. Janet Pratt (former Westinghouse employee) : At first I thought, "Are you crazy? Do you think I'm going to go down there and help you out [after you took my job away]?" I wanted to find out where my job was; where it had went. So that's why I decided to go. What I found there was a completely different world. You get into Juarez and [see] nothing but rundown shacks. And they were hard-working people. They were working, doing the same thing I had done up here [in Indiana]. But they were doing it for 85 cents an hour. -

Sullivan-Type Principles for U.S. Multinationals in Emerging

"SULLIVAN-TYPE" PRINCIPLES FOR U.S. MULTINATIONALS IN EMERGING ECONOMIES RICHARD T. DE GEORGE* 1. INTRODUCTION The high rate of crime in Russia and the prominence of the Russian Mafia are well known and publicized in the West. President Yeltsin has called crime, which is choking the emerging market economy, Russia's biggest problem.' An article in U.S. News & World Report describes Russia as "a vast bazaar in which the easiest way to get rich is to steal."2 The government has shown itself ineffective in combating crime and in establishing a rule of law. Consequently, many ordinary Russians, who are experiencing a decline in their standard of living,3 are more ambivalent about the march towards capitalism than they were in 1991. Many Western businesses are understandably reluctant to enter an area in which corruption is rampant and the future uncertain. However, the reasons behind the present conditions are too often inadequately understood. As a result, the remedy and the appropriate role of Western companies in the developing market of countries of the former Soviet Union are not clearly * Richard T. De George is University Distinguished Professor of Philosophy, of Russian and East European Studies, and of Business Administration, and Director of the International Center for Ethics in Business at the University of Kansas. His books include The New Marxism; Soviet Ethics and Morality; Business Ethics; and Competing with Integrity in International Business. 1 He has frequently called fighting crime his top priority. See Jack F. Matlock, Russia: The Power of the Mob, NY REVIEW OF BOOKS, July 13, 1995, at 12, 13; see also Julie Corwin et al., The Looting of Russia, U.S. -

Greenwash: Corporate Environmental Disclosure Under Threat of Audit∗

Greenwash: Corporate Environmental Disclosure under Threat of Audit∗ Thomas P. Lyon†and John W. Maxwell‡ May 23, 2007 Abstract We present an economic model of greenwash, in which a firm strategi- cally discloses environmental information and a non-governmental organi- zation (NGO) may audit and penalize the firm for failing to fully disclose its environmental impacts. We show that disclosures increase when the likelihood of good environmental performance is lower. Firms with in- termediate levels of environmental performance are more likely to engage in greenwash. Under certain conditions, NGO punishment of greenwash induces the firm to become less rather than more forthcoming about its environmental performance. We also show that complementarities with NGO auditing may justify public policies encouraging firms to adopt en- vironmental management systems. 1Introduction The most notable environmental trend in recent years has been the shift away from traditional regulation and towards voluntary programs by government and industry. Thousands of firms participate in the Environmental Protec- tion Agency’s partnership programs, and many others participate in industry- led environmental programs such as those of the World Business Council for Sustainable Development, the Chicago Climate Exchange, and the American Chemistry Council’s “Responsible Care” program.1 However, there is growing scholarly concern that these programs fail to deliver meaningful environmental ∗We would like to thank Mike Baye, Rick Harbaugh, Charlie Kolstad, John Morgan, Michael Rauh, and participants in seminars at the American Economic Association meetings, Canadian Resource and Environmental Economics meetings, Dartmouth, Indiana University, Northwestern, UC Berkeley, UC Santa Barbara and University of Florida for their helpful comments.