The Transition of Monetary System in East Asia Based on Korean Sources

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

340336 1 En Bookbackmatter 251..302

A List of Historical Texts 《安禄山事迹》 《楚辭 Á 招魂》 《楚辭注》 《打馬》 《打馬格》 《打馬錄》 《打馬圖經》 《打馬圖示》 《打馬圖序》 《大錢圖錄》 《道教援神契》 《冬月洛城北謁玄元皇帝廟》 《風俗通義 Á 正失》 《佛说七千佛神符經》 《宮詞》 《古博經》 《古今圖書集成》 《古泉匯》 《古事記》 《韓非子 Á 外儲說左上》 《韓非子》 《漢書 Á 武帝記》 《漢書 Á 遊俠傳》 《和漢古今泉貨鑒》 《後漢書 Á 許升婁傳》 《黃帝金匱》 《黃神越章》 《江南曲》 《金鑾密记》 《經國集》 《舊唐書 Á 玄宗本紀》 《舊唐書 Á 職官志 Á 三平准令條》 《開元別記》 © Springer Science+Business Media Singapore 2016 251 A.C. Fang and F. Thierry (eds.), The Language and Iconography of Chinese Charms, DOI 10.1007/978-981-10-1793-3 252 A List of Historical Texts 《開元天寶遺事 Á 卷二 Á 戲擲金錢》 《開元天寶遺事 Á 卷三》 《雷霆咒》 《類編長安志》 《歷代錢譜》 《歷代泉譜》 《歷代神仙通鑑》 《聊斋志異》 《遼史 Á 兵衛志》 《六甲祕祝》 《六甲通靈符》 《六甲陰陽符》 《論語 Á 陽貨》 《曲江對雨》 《全唐詩 Á 卷八七五 Á 司馬承禎含象鑒文》 《泉志 Á 卷十五 Á 厭勝品》 《勸學詩》 《群書類叢》 《日本書紀》 《三教論衡》 《尚書》 《尚書考靈曜》 《神清咒》 《詩經》 《十二真君傳》 《史記 Á 宋微子世家 Á 第八》 《史記 Á 吳王濞列傳》 《事物绀珠》 《漱玉集》 《說苑 Á 正諫篇》 《司馬承禎含象鑒文》 《私教類聚》 《宋史 Á 卷一百五十一 Á 志第一百四 Á 輿服三 Á 天子之服 皇太子附 后妃之 服 命婦附》 《宋史 Á 卷一百五十二 Á 志第一百五 Á 輿服四 Á 諸臣服上》 《搜神記》 《太平洞極經》 《太平廣記》 《太平御覽》 《太上感應篇》 《太上咒》 《唐會要 Á 卷八十三 Á 嫁娶 Á 建中元年十一月十六日條》 《唐兩京城坊考 Á 卷三》 《唐六典 Á 卷二十 Á 左藏令務》 《天曹地府祭》 A List of Historical Texts 253 《天罡咒》 《通志》 《圖畫見聞志》 《退宮人》 《萬葉集》 《倭名类聚抄》 《五代會要 Á 卷二十九》 《五行大義》 《西京雜記 Á 卷下 Á 陸博術》 《仙人篇》 《新唐書 Á 食貨志》 《新撰陰陽書》 《續錢譜》 《續日本記》 《續資治通鑑》 《延喜式》 《顏氏家訓 Á 雜藝》 《鹽鐵論 Á 授時》 《易經 Á 泰》 《弈旨》 《玉芝堂談薈》 《元史 Á 卷七十八 Á 志第二十八 Á 輿服一 儀衛附》 《雲笈七籖 Á 卷七 Á 符圖部》 《雲笈七籖 Á 卷七 Á 三洞經教部》 《韻府帬玉》 《戰國策 Á 齊策》 《直齋書錄解題》 《周易》 《莊子 Á 天地》 《資治通鑒 Á 卷二百一十六 Á 唐紀三十二 Á 玄宗八載》 《資治通鑒 Á 卷二一六 Á 唐天寶十載》 A Chronology of Chinese Dynasties and Periods ca. -

Mind-Seal of the Buddhas

MindMind SealSeal ofof TheThe BuddhasBuddhas Patriach Ou-i's Commentary on the Amitabha Sutra Translated by J.C. Cleary HAN DD ET U 'S B B O RY eOK LIBRA E-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.buddhanet.net Buddha Dharma Education Association Inc. Mind-Seal of the Buddhas Patriarch Ou-i’s Commentary on the Amitabha Sutra Translated by J.C. Cleary Foreword, Notes and Glossary by Van Hien Study Group 2 3 This book is a translation from the Chinese of a major commentary on the Amitabha Sutra, the key text of Pure Land Buddhism. Its author is the distinguished seventeenth century T’ien-T’ai Master Ou-i, subsequently honored as the ninth Patriarch of the Pure Land school. To our knowledge, it is the first time this work has ever been rendered into a Western language. Chinese title: Vietnamese title: Cover Illustration (page 2) Amitabha Buddha with the mudra of rebirth in the Western Paradise Painting on silk 18th century, National Museum of Korea, Seoul. Sutra Translation Committee of the United States and Canada New York - San Francisco - Niagara Falls - Toronto, 1996 4 5 Editors’ Foreword Of all the forms of Buddhism currently practiced in Asia, Pure Land has been the most widespread for the past thousand years. At the core of this school is a text of great beauty and poetry, the Amitabha Sutra, intoned every evening in count- less temples and homes throughout the Mahayana world. This important text shares with the Avatamsaka and Brahma Net sutras the distinction of being among the few key scriptures preached spontaneously by the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas, without the customary request from the assembly. -

Buddhism in China

«MW«MMM PRINCETON, N. J. BL 1430 .B42 1884 ^ Heal, Samuel, 1825-1889 Buddhism in China SAelf. BUDDHISM IN CHINA AMAF lo illusuat.- ^....>.^^: BUDDHISM IN CHINA -^'"' _^fii^,Mi^i^^ \\Th^,i„„„- : . Uphi . ^-~-^-=-J.<iQ.,;^gi(-=~^:'-v Londnn PiiUmbi d l.v iliu S.i.i,-fy r..r IVjuiuUn);" Christian Ko..wli..lg<,. Bon--Cf)riEitian Hdi'gi'ousi ^psftemSi BUDDHISM IN CHINA. BY THE REV. S. BEAL, RECTOR OF WARK-ON-TYNR, NORTHUMBERLAND. PUBLISHED UNDER THE DIRECTION OF THE COMMITTEE OF GENERAL LITERATURE AND EDUCATION APPOINTED BY THE SOCIETY FOR PROMOTING CHRISTIAN KNOWLEDGE. LONDON: SOCIETY FOR PROMOTING CHRISTIAN KNOWLEDGE, NORTHUMBERLAND AVENUE, CHARING CROSS, W.C. 43, QUEEN VICTORIA STREET, E.C. 26, ST. George's place, hyde park corner, s.w. BRIGHTON : 135, north street. New York : E. & J. B. YOUNG & CO. 1884. CONTENTS. CHAPTER I. Introductory CHAPTER II. Whence our Knowledge of the Northern Books has been derived ... ... ... ... ... ... ... lo CHAPTER III. Agreement between Early Northern and Southern Books... 22 CHAPTER IV. Historical Connexion between India and China ... ... 42 CHAPTER V. The Dream of Ming-ti ... ... ... ... ... 51 VI BUDDHISM IN CHINA. CHAPTER VI. The Origin of the Sakyas ... 54 CHAPTER VH. The Legend of Sakya Buddha 69 CHAPTER VHL The "Lifeof Buddha," by Ajvaghosha ... 72 CHAPTER IX. Subsequent History of Buddhism in China (Historical Connexion) ... ... ... ... 90 CHAPTER X. Buddhism in its Philosophical and Religious Aspects ... 98 CHAPTER XL The Worship of Kwan-yin ... ... ... ... .., 119 CHAPTER XII. The Western Paradise of the Buddhists CONTENTS. Vll CHAPTER Xril. Ritual Services of Kwan-yin ... ... ... ... ... 133 CHAPTER XIV. Amitabha .. ... ... ... ... ... ... 159 CHAPTER XV. -

The Marriage Charm Free

FREE THE MARRIAGE CHARM PDF Linda Lael Miller | 304 pages | 27 Jan 2015 | Harlequin Books | 9780373778928 | English | Don Mills, Ontario, United States Ancient Chinese Marriage Charms The right husbands. One already has: Hadleigh Stevens, who married rancher Tripp Galloway a few months ago. Melody has recently found success as a jewelry designer, and her work is the focus of her life. The characters The Marriage Charm regular people and they deal with fairly normal life situations. You can tell Miller knows her setting — the descriptions of small towns and rural mountain areas made me feel like I was right there. It all added up to an enjoyable way to spend a few hours reading. ISBN Raised in Northport, Washington, the self-confessed barn goddess now lives in Spokane, Washington. She also loves to hear from readers by mail at P. BoxSpokane, WA Like Like. I have this book on my tbr shelf. I always enjoy LLM books. This one does sound like a light and charming read. Thanks for sharing your thoughts. Share this: Share Tweet. Like this: Like Loading I have read her before! A good friend of mine loves her books! This one sounds awfully charming, Mary. Terrific review! Glad you The Marriage Charm this read. Thanks for sharing. Post The Marriage Charm Cancel. By continuing to use this website, you agree to their use. To find out more, including how to control cookies, see here: Cookie Policy. WEDDING CHARMS - These coin charms often imitate the design of Chinese cash coinsbut can exist in many different shapes and sizes. -

Researches Into Chinese Superstitions" Deals with the Form, Mode of Writing, and Explanation of Charms and Spells

INTO CHINESE SUPEHSTITIOXS By Henry Dore, S.J. TRANSLATED FROM THE FRENCH V li I WITH NOTES, HISTORICAL. AND EXPLANATORY By M. Kennelly, S.J. In First Part SUPERSTITIOUS PRACTICES Profusely illustrated Vol. Ill T'USEWEI PRINTING PRESS Shanghai 1916 \ Gettysburg College Library Gettysburg, Pa. RARE BOOK COLLECTION Gift of Dr. Frank H. Kramer Accession 10l|l|8U Shelf DS721.D72 v.3 <x lev ic INTO CHINESE SUPERSTITIONS By Henry Dore, S.J. TRANSLATED FROM THE FRENCH WITH NOTES, HISTORICAL AND EXPLANATORY By M. Kennelly, S.J. First Part SUPERSTITIOUS PRACTICES Profusely illustrated Vol. Ill T'USEWEI PRINTING PRESS Shanghai 191(7 PREFACE. This third volume of "Researches into Chinese Superstitions" deals with the form, mode of writing, and explanation of charms and spells. Completing- as it does the doctrine and popular notions contained in the two preceding volumes, it finds its natural and logical place here. In the French series, the Author published it as Volume V. This was owing to the difficulty he experienced in elucidating the abstruse principles, the mythical and phantastic inventions, the medley of Taoist and Buddhist philosophy which form the basis of charm writing. Taoism has influenced Confu- cianism. Kw'ei-sing $| jj|, the God of Literature, and as such worshipped by all students, is of Taoist origin. In pictures of him, he is represented as a demon-like personage, standing on one leg, and with the other kicking the Dipper, which is regarded as his palace. He holds in one hand an immense pencil, and in the other a cap for graduates (I). -

Ming China: Courts and Contacts 1400–1450

Ming China: Courts and Contacts 1400–1450 Edited by Craig Clunas, Jessica Harrison-Hall and Luk Yu-ping Publishers Research and publication supported by the Arts and The British Museum Humanities Research Council Great Russell Street London wc1b 3dg Series editor The Ming conference was generously supported by Sarah Faulks The Sir Percival David Foundation Percival David Foundation Ming China: Courts and Contacts 1400–1450 Edited by Craig Clunas, Jessica Harrison-Hall This publication is made possible in part by a grant from and Luk Yu-ping the James P. Geiss Foundation, a non-profit foundation that sponsors research on China’s Ming dynasty isbn 978 0 86159 205 0 (1368–1644) issn 1747 3640 Names of institutions appear according to the conventions of international copyright law and have no other significance. The names shown and the designations used on the map on pp. viii–ix do not imply official endorsement Research and publication supported by Eskenazi Ltd. or acceptance by the British Museum. London © The Trustees of the British Museum 2016 Text by British Museum staff © 2016 The Trustees of the British Museum 2016. All other text © 2016 individual This publication arises from research funded by the contributors as listed on pp. iii–v John Fell Oxford University Press (OUP) Research Fund Front cover: Gold pillow end, one of a pair, inlaid with jewels, 1425–35. British Museum, London (1949,1213.1) Pg. vi: Anonymous, The Lion and His Keeper, Ming dynasty, c. 1400–1500. Hanging scroll, ink and colours on silk. Image: height 163.4cm, width 100cm; with mount: height 254.2cm, width 108cm. -

Playthings in Porcelain Siamese Pee in the National Museum of Ethnology

PLAYTHINGS IN PORCELAIN SIAMESE PEE IN THE NATIONAL MUSEUM OF ETHNOLOGY Illustration XVII from the article Siamesische und Chinesisch-Siamesische Münzen in the series Internationales Archiv für Ethnographie, Bd II, Leiden c. 1890. Colophon Text Paul L.F. van Dongen ©, in collaboration with Nandana Chutiwongs English translation Enid Perlin Editors Paul L.F. van Dongen & Marlies Jansen Photography Ben Grishaaver Museum website www.rmv.nl The Curators Paul L.F. van Dongen (e-mail: mailto:[email protected]) Nandana Chutiwongs (e-mail: mailto:[email protected]) PLAYTHINGS IN PORCELAIN. SIAMESE PEE IN THE NATIONAL MUSEUM OF ETHNOLOGY. PAUL VAN DONGEN © Digital publications from the National Museum of Ethnology Contents Introduction 1. The collection - The collector - The questions - The answers - Money must move - The miraculous increase 2. Thai currency - For barter and for gain - Value for money - Money and more money - An unusual type of money 3. The Chinese in Thailand - Trade and travel - Non-alien foreigners - Integration and cultural conflation - Genetic passion - The gambling houses - The favourite games of chance - Where money should not roll 4. Money-value tokens - The non-porcelain tokens - ‘Circulating treasures’ - Circulation and Distribution - Duration of use 5. ‘Made in China’ - Mass production - Shapes - Motifs and decorations - Explanations of the signs o Chinese inscriptions o Values and numbers o The gambling houses o Common sayings o The ‘ brand marks’ o Thai inscriptions 6. Postscript Literature Notes 1 PLAYTHINGS IN PORCELAIN. SIAMESE PEE IN THE NATIONAL MUSEUM OF ETHNOLOGY. PAUL VAN DONGEN © Digital publications from the National Museum of Ethnology Introduction Fired porcelain money for use in gambling, with Chinese or Thai inscriptions, and appearing in many shapes: colourful, yet one time having a real value. -

Transcript of the Acoustiguide Audio Tour

1 Kimbell Art Museum Transcript of the Acoustiguide Audio Tour Production #4250 © Acoustiguide Inc. and Kimbell Art Museum, 2021. All rights reserved. 2 STOP LIST 1. Director’s Welcome and Introduction Buddha, Shiva, Lotus, Dragon: The Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd Collection at Asia Society 2. John D. Rockefeller 3rd Collection John D. Rockefeller 3rd, Sherman E. Lee, and the Building of a Collection BUDDHIST ART 3. The Buddha Buddha, India (probably Bihar), Gupta, late 6th c. (1979.8) 4. Buddhas and Bodhisattvas Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara in the Form of Kharsarpana Lokeshvara, India (Bihar or Bengal), Pala period, late 11th–early 12th c. (1979.40) 5. Transmission of Buddhism Pair of Bodhisattvas in the Pensive Pose, China, Northern Qi period, dated 570 (1992.4) 6. Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara, Nepal, Early Malla period, late 13th–early 14th c. (1979.51) 7. Crowned Buddha Shakyamuni, Kashmir or Northern Pakistan, 8th c. (1979.44) 8. Crowned Buddha Seated in Meditation and Sheltered by Muchilinda, Cambodia, Angkor period, Angkor Wat style, possibly 12th c. (1979.68a-c) CERAMICS AND METALWORK 9. Ceramics and Metalwork Food Vessel (Gui), China, Eastern Zhou period, ca. 6th c. BC (1979.103a, b) 10. Figure of a Court Lady and Footed Dish (sancai ware), China, Tang period, 8th c. (1979.113 and 1979.128) 11. Brush Washer and Bowl (Jun ware), China, Northern Song period, early 12th c. (1979.138, 1979.137); Cusped Bowl (Yaozhou ware), China, Northern Song period, ca. early 12th c. (1979.131); and Censer (Ge ware), China, Yuan period, 13th–14th c. (1979.146) 12. -

Lee H. Gong Error Coins Leading Expert Extols Coin Errors and How These Happen at the Mint

Numismatic Summer 2009 California State Association of V. 6, No. 2 Numismatic Southern California $7.95 Association The California Numismatist See us at the Los Angeles Summer ANA coin show at table #335 Collections ExperienceE i Singles Integrity Sets Honesty Gold Financial strength Silver Professional Copper Confidential Early type Life: ANA, CSNA, Liberty seated CSNS, FUN, NASC Morgan/Peace dollars We buy it all! If you have coins to sell, Retailer—we can pay see us first. You'll see more because we sell to why we are one of the the public one on one. most fair and respected dealers in California. Eliminate the "middle man"—we buy over 85% We are buying, buying, of our coins from other buying! dealers. Michael Aron Rare Coins Tel (949) 489-8570 Fax (949) 489-8233 www.coindaddy.com [email protected] —serving the numismatic community since 1972— The California Numismatist Offi cial Publication of the California State Numismatic Association and the Numismatic Association of Southern California Summer 2009, Volume 6, Number 2 About the Cover The California Numismatist Staff Tom Fitzgerald has written a summary Editor Greg Burns of the beautiful Lincoln cents which he P.O. Box 1181 calls the “king of the US coins”. Our 16th Claremont, CA 91711 president’s image has graced our most fun- [email protected] damental coin for a century now, a fi tting tribute to the great man who rose to the Club Virginia Bourke tortuous occasion forced upon him by the Reports 10601 Vista Camino turbulence of our civil war. One hundred South Lakeside, CA 92040 and forty-four years after it’s conclusion [email protected] it’s diffi cult to look back and understand the sources of such discord. -

Room 68 Money

Large print information Please do not remove from this display Money Gallery From prehistory to the present day Plan Introduction 1. Electrum coin, Lydia This gallery displays the history of 1 (modern Turkey), about 650 BC money around the world. From the 2 2. Amarna hoard, Egypt, about 1350–1300 BC earliest evidence, more than 4000 years ago, to the latest developments 3. Great Ming circulating treasure note, China, AD 1375 in digital technology, money has been an important part of human societies. 4. Weight for measuring gold dust, Asante Looking at the history of money gives Empire (West Africa), 1800s 3 us a way to understand the history of 5. Medal satirising the banker John Law, the world. 4 Germany, 1720 6. Mondex machine, UK, 1990s 5 6 Case 1 Map: The Eastern Mediterranean, Case 1 about 650–500 BC The The beginnings The beginnings beginnings Image: Parts of a bronze belt attachment of coinage of coinage of coinage from Lydia with lion-head designs Lydia © Trustees of the British Museum Lydia Lydia The earliest coins about 650–450 BC Electrum coins, about 650 BC, Lydia (modern Turkey) The frst coins were probably produced and used in Lydia, now central Turkey. These are some of the earliest coins They were made from electrum, in the world. Made from electrum, a a naturally occurring mixture of gold naturally occurring mixture of gold and silver. They were made to particular and silver, they were issued in Lydia. weights. Although irregular in size and shape, these early coins were produced We are not sure why the frst coins were according to a strict weight standard. -

Small Amitabha Sutra

The Buddha Speaks of Amitabha Sutra Translated into Chinese by: Tripitaka Dharma Master Kumarajiva during the Yao Qin Dynasty Based on the English Translation by: Buddhist Text Translation Society A General Explanation by: Master YongHua Lu Mountain Temple 7509 Mooney Drive Rosemead, CA 91770 USA Tel: (626) 280-8801 1st edition, ISBN 978-0-9835279-1-6, © Copyright: Bodhi Light International, Inc. www.BLI2PL.org SPECIAL ACKNOWLEDGMENT I would like express my profound gratitude for the count- less hours that my students and supporters put into the production of this Sutra. Much of the information about the Buddha's disciples in this commentary is copied from Master Hsuan Hua's commentary of the same name. His work is also used as a source book throughout. I encourage the reader to reference Master Xuan Hua’s books, published by the Buddhist Text Translation Socie- ty, for further information. In addition, I would like to thank the Buddhist Text Translation Society for this translation of the Amitabha Sutra. Master YongHua July, 2012 Amitabha Buddha Guan Yin Bodhisattva Great Strength Bodhisattva Contents INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................... 1 Five Major Schools of Asian Buddhism .......................................................... 1 Translator ......................................................................................................... 6 Tian Tai 5-fold profound meanings: ............................................................... 14 Explaining -

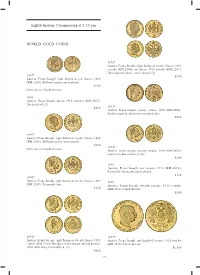

Eighth Session, Commencing at 2.30 Pm WORLD GOLD COINS

Eighth Session, Commencing at 2.30 pm WORLD GOLD COINS 1892* Austria, Franz Joseph, eight fl orins or twenty francs, 1892 restrike (KM.2269); one ducat, 1915 restrike (KM.2267). Uncirculated; choice uncirculated. (2) 1887* $350 Austria, Franz Joseph, four fl orins or ten francs, 1885 (KM.2260). Brilliant, nearly uncirculated. $150 Private purchase from Monetarium. 1888 Austria, Franz Joseph, ducat, 1915 restrikes (KM.2267). Uncirculated. (2) $260 1893* Austria, Franz Joseph, twenty corona, 1893 (KM.2806). Surface marked, otherwise extremely fi ne. $300 1889* Austria, Franz Joseph, eight fl orins or twenty francs, 1885 (KM.2269). Brilliant, nearly uncirculated. $300 1894* Private purchase from Monetarium. Austria, Franz Joseph, twenty corona, 1894 (KM.2806). Good very fi ne/extremely fi ne. $240 1895 Austria, Franz Joseph, ten corona, 1911 (KM.2816). Extremely fi ne/nearly uncirculated. $120 1890* Austria, Franz Joseph, eight fl orins or twenty francs, 1889 1896 (KM.2269). Extremely fi ne. Austria, Franz Joseph, twenty corona, 1915 restrike $220 (KM.2818). Uncirculated. $240 1891* 1897* Austria, Franz Joseph, eight fl orins or twenty francs, 1892 Austria, Franz Joseph, one hundred corona, 1915 restrike restrike (KM.2269); Hungary, Franz Joseph, twenty korona, (KM.2819). Uncirculated. 1896 (KM.486). Uncirculated. (2) $1,500 $600 223 Rare Specimen Issue 1908C Sovereign 1898* Belgium, Leopold II, twenty francs, 1871 (KM.31). Nearly uncirculated. $300 Private purchase from Monetarium. 1899 Belgium, Leopold II, twenty francs, 1877 (KM.37); Netherlands, Wilhelmina, ten gulden, 1933 (KM.162). Extremely fi ne; nearly uncirculated. (2) $600 1900* Brazil, Pedro II, 10,000 reis, 1884 (KM.467).