Susan R. Ki,Ng

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Calder to Koons, the Growing Demand for Wearable

From Calder to Koons, the growing demand for wearable art Annachiara Biondi | March 7, 2018 As an exhibition dedicated to artist-made jewellery opens at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris, Vogue talks to the show's co-curator Diane Venet and other experts about the flourishing intersection of fashion and art. NEXT Image: Damian Noszkowicz When Artists’ Jewellery: From Calder to Koons opens at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs (MAD) on March 7, it marks not only a curatorial coup, but the apotheosis of a burgeoning market. Conceived by Diane Venet, a leading collector of artist-made jewellery, and Karine Lacquemant, assistant curator of the modern and contemporary department at MAD, the show will feature 258 pieces created by 150 different artists. Many of the pieces will be displayed alongside original artworks by the same artist for the first time—a feat made possible by the museum’s vast collection and Venet’s extensive connections in the art world, which has resulted in a number of significant loans. By presenting jewellery alongside other art forms, the exhibition’s design—realised by interior architect Antoine Plazanet and graphic designers ÉricandMarie—makes a powerful statement about their intellectual and artistic value. “My aim was to explain definitively that artist jewellery is art and not jewellery,” Venet tells Vogue over the phone from Paris a week before the show opens. “An artist is doing jewellery, most of the time, for the woman they love or [for] a great friend, but it’s always related to their main work,” the collector and curator continues. -

National Institute of Fashion Technology

National Institute of Fashion Technology A Statutory Institute governed by the NIFT Act 2006 Ministry of Textiles, Government of India NIFT Campus, Hauz Khas, Opposite Gulmohar Park, New Delhi - 110016 National Institute Of Fashion Technology 29th Annual Report 2014-15 21.09.2015 NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF FASHION TECHNOLOGY | ANNUAL REPORT 2014-15 CONTENTS 01 Board of Governors (2014-15) 77 Design Space 05 NIFT - Introduction 83 International & Domestic Linkages 07 Significant Landmarks (2014-15) 86 National Resource Centre 08 Student Development Activities 87 Cluster Development Inititative 09 NIFT Campuses 91 Information Technology Inititative ACADEMIC DEPARTMENTS 93 Continuing Education Programme 11 Fashion Design 97 Campus Placements 19 Leather Design 101 Ph.D. and Research 27 Textile Design 110 FOTD 37 Knitwear Design 112 Admissions 2014 45 Fashion & Lifestyle Accessories 113 Convocation 2014 53 Fashion Communication 114 Abbreviations 61 Fashion Technology Auditor’s Report & 71 Fashion Management Studies 116 Statement of Accounts NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF FASHION TECHNOLOGY | ANNUAL REPORT 2014-15 BOARD OF GOVERNORS Members as on March 2015 Smt. Kiran Dhingra, IAS (Retd.) 83 C Village Chairperson BOG NIFT Gancim- Bhatim Post Office Goa Velha Talukh Tisvadi Goa – 403108 Sh. Naresh Gujral 5, Amrita Shergil Marg Hon’ble M.P Rajya Sabha New Delhi-110003 (22-07-2014 up to 31-03-2015) Shri S. Selvakumara Chinnayan, S-3, SCP Residency, Hon’ble M.P Lok Sabha BVB School Main Road, Thindal, (21-10-2014 up to 31-03-2015) Distt. Erode- 638 012 Tamil Nadu Smt. Poonam Mahajan, Block no. 2 Bhima Worli Sagar Hon’ble M.P Lok Sabha Cooperative Society (21-10-2014 up to 31-03-2015) Dr. -

2017 Proceedings St

2017 Proceedings St. Petersburg, Florida Mystic Girls and Butterflies - CNIII Ling Zhang, Central Michigan University, USA Brent Holland, Iowa State University, USA Keywords: Digital textile printing, 3D printing, wearable art, fabric space Fashion designers, especially wearable art designers, often explore fine art drawings as sources of inspiration. Collaborations between wearable art designers and fine artists occurred not only in contemporary fashion world, but can be traced back to the 19th century, and bloomed in the early 20th (Mackrell, 2005). Many famous designers in the 20th century collaborated with artists to create representative works establishing their position in the field of fashion. One of the most famous and successful collections derived from fine art, Mondrian Look, was designed by Yves Saint Laurent in 1965-1966. For Mystic Girls and Butterflies, a piece of wearable art, the designer was inspired by an experimental drawing titled CN-III, created by the collaborating artist. For CN-III, the artist used figurative representation and formal abstraction to create multilayered meditations upon time, space and a particular sphere of existence. The goal of this experimental drawing was to print multiple digital drawings on separate sheets of clear plastic. All the printed plastic images were stacked together to create one, two and a half-dimensional image. In CN-III, thousands of lines and shapes to translate complex spatial relationships between people, places and things familiar to the artist. Thus, the purposes of creating this piece of wearable art were to: (a) experiment utilizing fabrics to emulate spatial relationships and (b) explore digital textile printing, 3D printing technologies, and handcraft techniques to transform a two and a half-dimensional drawing to three-dimensional garment. -

Preparing for the 2021 4-H Fashion Show

Preparing for the 2021 4-H Fashion Show Showcasing Constructed and Purchased Garments Douglas-Sarpy Counties March 2021 The Sarpy County Fair Fashion Show is a fun event that many 4-H members look forward to each year. The purpose of the 4-H Fashion Show is to: • Build self-confidence and poise. • Develop skills in planning, selecting, and making clothing for different occasions. • Develop “fashion know how” by creating a total look with the garment, accessories, and hairstyle. • Develop good posture and grooming habits. Any 4-H member including Clover Kids exhibiting a Clothing, Beyond the Needle, Shopping In Style/Consumer Management, Fiber Arts or Quilt Quest/Wearable Art project may enter a garment in the 4-H Fashion Show. • Clover Kids may participate if they have a wearable garment such as an Embellished Garment from the Beyond the Needle division or a clothing project from Sewing for Fun or Clothing Level 1. Pillows or other items not considered a wearable garment cannot be modeled. • To enter the Fashion Show, complete the Fashion Show Entry Form. The entry deadline is Thursday, July 8th. The entry form is available at the end of this section. There is no entry fee. Shopping in Style entries also need to submit the written report pages of the entry form. • To receive your ribbon and premium for the Fashion Show, you must th o participate in the judging portion of the 4-H Fashion Show on Thursday, July 15 2021 o exhibit your project at the Sarpy County Fair th o and model in the Sarpy County Fair 4-H Fashion Show on Wednesday, August 4 at 6:00 pm • Participants for the Fashion Show may model up to two projects on judging day, July 15th. -

Wearable Artwork & the Design Process

Sarah Blanke Research Week Symposium Submission Undergraduate Research Symposium Submission Title – Spindles of Stardust Program of Study – Fashion Design Presentation Type – Choose one of the following: PowerPoint (Remote) Mentor(s) and Mentor Email – Matalie Howard ([email protected]) Student name(s) and email(s) – Sarah Blanke ([email protected]) Category – Creative and Artistic Abstract The overall purpose of this garment is to represent the beauty, intricacy, and weightlessness that can be found in the spiral galaxies of outer space in a wearable piece that is congruent with modern fashions. While couture garments and wearable art are certainly pieces to be admired, they are not often relevant once taken off the runway. Through the design of this garment, relevance with the runway as well as wearable formal wear have been embodied, bridging the gap between these two areas of fashion. The inspiration of a spiral galaxy was chosen due to the variety of colors found in these galaxies, as well as the beautiful movement they display. While a much of natural beauty is observable with the naked eye, a great deal are still overlooked. This piece draws attention to just one of these forgotten wonders, embodying the elegance and beauty that exists in our universe. The galaxies are massive, yet are made up by smaller details that come together to form the whole. This principle has been largely implemented into the construction of the garment. A major inspiration piece lies in the metallic spiral detailing of the belt and straps, which swirl in a similar manner to the galaxies they represent. -

The Wonders of Wearable Art

THE WONDERS OF WEARABLE ART At left: Susan Holmes: Parachute Bride which won I write this article as a confessed Wearable Art Tragic. 2nd prize in the Spark Digital Creative Excellence I love the notion of it and the way I have seen that notion Section, WOW 2014. Made from a 1939 silk manifest itself in the Antipodes, chiefly in New Zealand parachute. Photo Phil Fogle which has turned out to be a world leader in WOW factors, Above: Susan Holmes, Rainbow Warrior, Winner Silk but also in Australia where I have lived for forty years, Section WOW 1993 and Runner-up to the Supreme having arrived from the USA in 1975. Award. Made of crinkle silk, appliquéd velvet, appliquéd stiffened shade cloth and nylon sail cloth. I decided it would be best to take readers on a personal Photo Phil Fogle journey into this amazingly rich area. There are so many manifestations that I feel almost as overwhelmed as a first-time visitor to the World of WearableArt Awards in WOW® is registered by the World of WearableArt™ Wellington New Zealand must surely feel. These days there (New Zealand). For the purposes of this article, are anywhere from 150 to 200 rigorously selected wearable WOW and World of WearableArt are used. These are artworks performed over 2 hours each Antipodean spring protected business names. for up to 14 performances. Above: Trophy by Svenja, shown in the Bizarre Bra section of So how to narrow the vision and still make it expansive? WOW® 2016: Antlers and animal heads, women and breasts, First I must request a willing suspension of disbelief. -

Investigating Interactive Biophilic Wearable Objects by Neda Fayazi

Investigating Interactive Biophilic Wearable Objects by Neda Fayazi A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Design in Industrial Design Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2014, Neda Fayazi ii ABSTRACT Designers apply different design elements such as form, colour, texture, light, and movement in the design of products. This interdisciplinary study aims to investigate the application of ‘biophilic movement’ in the design of interactive wearable objects, given that incorporating both natural inspiration (discipline of biology) and physical movement in the design of products can create a pleasurable experience for the users. In order to investigate how designers might incorporate ‘biophilic movement’ in the design of products, this research draws from the discipline of biology. The study applies inspiration derived from plant and animal movements, which have positive impacts on human psychology. Furthermore, this study takes a user-centered approach by applying different methods: exploring the people’s emotional response to different biophilic movements incorporated in designed wearable objects. Based on these emotional responses, this thesis suggests that biophilic movement can potentially create a pleasurable experience and enhance the interaction between people and wearable objects with biophilic movements . The key findings of this study include: 1) Adding biophilic movement can add interest to biophilic wearable objects by engaging the people who interact with it; 2) Identifying and categorizing biologically inspired movements can help designers in the area of biology-to-design; and 3) Presenting a biophilic semantic differential scale that can be used to understand how people interpret movements in biophilic artifacts. -

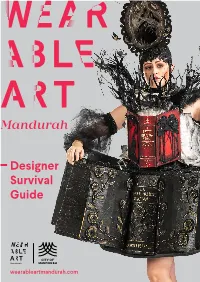

Designer Survival Guide

Designer Survival Guide wearableartmandurah.com 1 Welcome Wearable Art Mandurah is the largest wearable art competition in Australia and an internationally recognised event that attracts a large, enthusiastic audience. Entries come from Mandurah, Western Australia, interstate and across the globe. • Great prize money • Workshops • Professional presentation • Professional development for participants • Publicity and exposure 2 Categories Avant Garde Push the boundaries of radical design, innovation, concept development and execution. Avant Garde puts the “revolutionary” into Wearable Art Mandurah. Migration Mandurah’s wetlands are known as a haven for intercontinental migratory birds, just as our city is home to people from across the globe. Explore the flow and flux of travelling populations, both human and wild. Black and White Strip your garment back to the essentials of form, texture and technique in the monochrome. Paper Accept the challenge of fabricating a 90% paper garment that demonstrates the fragility and resilience of the material! Successful entries will be displayed in the Alcoa Mandurah Art Gallery. Tertiary The Tertiary Student category is for students registered at universities, TAFE institutions or government approved registered training organisations by 23 June 2021. Tertiary Pairing project An opportunity for tertiary students to collaborate and explore the concept of migration with others, perhaps far away! These entrants will be nominated by, or have the support of, their tertiary institution to be paired with another -

Trashion Fashion Show, 2021 Rules of Entry and Application

The th 11 Annual Trashion Fashion Show, 2021 Rules of Entry and Application *Application Deadline: Monday, March 8, 5:00pm Event date: Saturday, April 10, 2021 Location: Sonoma Community Center, 276 East Napa St, Sonoma 95476 - VIRTUAL RUNWAY SHOW (Covid-19 Health Protocols in order at all times.) Eligibility: Ages 9+ MANDATORY ATTENDANCE FOR APPLICANTS: ● FRIDAY, APRIL 9. (REHEARSAL WITH RUNWAY COACH): Available between 4 – 9:30pm for a mandatory scheduled appointment to rehearse at the Sonoma Community Center. All models must be prepared to change into their outfits and practice with the shoes, hats and any accessories to be worn in the show. ● SATURDAY, APRIL 10. (ONE VIRTUAL RUNWAY SHOW @ 4:00pm): Participants must be available from 1 - 5:30pm on April 10. How to apply: Mail or hand-deliver completed application form and fee to: c/o Eric Jackson, Creative Programs Manager Sonoma Community Center 276 E. Napa Street, Sonoma, CA 95476 Application fees: (non refundable or transferable) * Checks can be made out to “SCC” ● Juniors (ages 9-17): $25 each garment. ● Adults (ages18+): $45 each garment. Rules of entry: ● Create a wearable outfit made of trash and recycled materials. Designs can be avante-garde, over-the-top wearable art. Designs can also be ready-to-wear garments that are passable for actual clothing items. All designs must be made of materials that have been previously used, rescued from the trash or recycling bin or previously used and purchased at a thrift store. Do not use materials that have not been previously used, even if you consider them trash. -

2018 Media Kit

2018 MEDIA KIT Website: wearableartmandurah.com facebook.com/wearableartmandurah/ Media Enquiries: [email protected] New to the 2018 competition is the Wearable Art Mandurah International Award, open to artists living Wearable Art outside Australia. There are five major components of Wearable Art Mandurah 2018: Mandurah • Design competition Wearable Art Mandurah will return in 2018 with • Skill development two showcase events to be held at the Mandurah • Workshops Performing Arts Centre (Western Australia) on 9 – 10 • Entertainment showcase and exhibition June and an exhibition throughout August. • Whispers progressive design project The premiere event of its kind in Australia, Wearable Art Mandurah now attracts entrants from across the world. The 2018 competition has seen the largest The amount of entrants, with 132 participants from Australia and abroad, including Singapore, China, the UK, India, New Zealand, Switzerland and Romania. Beginnings Wearable Art Mandurah began in 2011 as the ‘Common Wearable Art Mandurah encourages new ways of Threads Wearable Art’ competition as part of the viewing the world through thought-provoking works of annual Stretch Arts Festival. In 2017 the project was art for the body. Encouraging people of all walks of life separated into a stand-alone event now known as to enter the competition and express their creativity, ‘Wearable Art Mandurah’. the event showcases artistic statements of individual, hand-made garments employing a variety of design mediums including fashion, textiles, industrial, fine art, jewellery, millinery, craft, sculpture and more. Every year, as part of the Wearable Art Mandurah competition, the best garments are selected for the showcase, which includes a creative and innovative production with garments showcased alongside music, dancing and theatre performances. -

Character Vests LESSON OVERVIEW STANDARDS

Teacher: Class: 2nd grade Duration: 2–3 class periods Course Unit: Lesson Title: Character Vests LESSON OVERVIEW Design is observed in the world around us on a daily basis. Fashion design combines the elements and principles of art and beauty to produce wearable art and clothing. In this lesson, students will follow the same design process as Nashville fashion designer Maarika Mann. Students will develop fantasy characters and then come up with wearable vests for their characters, using recyclable materials. Key terms include: fashion design, recycled fashion, repurpose, imagination, resourcefulness, fantasy, and prototype. STANDARDS Tennessee State Standards Visual Art—Grade 2 1.1 Use tools and media consistently in a safe and responsible manner. 1.2 Demonstrate an understanding of a variety of techniques. 2.1 Identify, understand, and apply the elements of art. 2.2 Identify, understand, and apply the principles of art. 3.1 Select subject matter, symbols, and ideas for the student’s own art. 5.1 Analyze the characteristics and merits of the student’s own work. 6.2 Understand connections between visual art and other disciplines in the curriculum. Common Core Connections for Integrated Subjects—Language Arts, Writing Language Arts—Grade 2 CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.3.2 Write informative/explanatory texts to examine a topic and convey ideas and information clearly. CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.3.2b Develop the topic with facts, definitions, and details. CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.3.3.A Establish a situation and introduce a narrator and/or characters; organize an event sequence that unfolds naturally. OBJECTIVES 1. Students will be able to define fashion design. -

Wearable Art – Embellished

Wearable Art – Embellished The main focus of the Wearable Art - Embellished category is using creative techniques and workmanship to decorate a purchased garment(s) for a unique one-of-a-kind outfit. The member uses arts/crafts techniques to embellish the garment to taste. The main entry must be an embellished garment (coat, dress, pants, shirt, etc.). Embellished accessories like shoes or a hat may complete the outfit. This category emphasizes creative techniques and workmanship as well as fit and coordination of the outfit. The objective is to provide the member a chance to sample and experiment with a variety of textile crafts. Youth are encouraged to demonstrate creativity, individualism and imagination in designing artistic wearable art. Examples of embellishments are, but are not limited to, the following: o fabric painting o beading o appliqués o embroidery (hand or machine) o tie dye o felting o button art Additional entry requirements for Wearable Art – Embellished are: o The one-page Wearable Art – Embellished information form o Front and back color photos of the original garment o Front and back full length color photos showing the member wearing the completed embellished garment(s). o The commentary – 60 words maximum 4-H Fashion Revue Information Form Wearable Art - Embellished Name ___________________________ County ________________________ Purchased garment(s) that were embellished (shirt, pants, jacket, etc.): _____________ ______________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________