Uniqueness in the Zulu Anthroponymic System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

01 Shamase FM.Fm

1 Relations between the Zulu people of Emperor Mpande and the Christian missionaries, c.1845-c.1871 Maxwell Z. Shamase 1 Department of History, University of Zululand [email protected] Abstract During Emperor Mpande's reign (1840-1872), following the deposition of his half-brother Dingane in 1840, the Zulu people mostly adhered to traditional norms and values, believing that the spirits of the dead live on. Ancestral veneration and the worship of the Supreme Being called Umvelinqangi were pre-eminent and the education of children was merely informal, based on imitation and observation. This worldview faced new challenges with the advent of Christianity and the arrival of Christian missionaries at Port Natal between 1845 and 1871. The strategy of almost all Christian missionaries was premised on winning the Zulu people en masse to Christianity through Mpande’s court. The doctrines preached by the missionaries disputed the fundamental ethical, metaphysical and social ideas of the Zulu people. Mpande, however, earnestly requested that at least one missionary reside in the vicinity of his palace. Nothing could deter Mpande’s attempts to use missionary connections to keep Colonial threats of invasion in check. While the Zulu people were devoid of organised religion which might have proved a bulwark against the Christianisation process, Mpande’s acceptance of the missionaries could be said to have been mainly strategic. He could not display bellicose tendencies while still at an embryonic stage of consolidating his authority. This paper gives an exposition of the nature and extent of relations between the Christian missionaries and the Zulu empire of Mpande. -

Guide to Missionary /World Christianity Bibles In

Guide to Missionary / World Christianity Bibles in the Yale Divinity Library Cataloged Collection The Divinity Library holds hundreds of Bibles and scripture portions that were translated and published by missionaries or prepared by church bodies throughout the world. Dating from the eighteenth century to the present day, these Bibles and scripture portions are currently divided between the historical Missionary Bible Collection held in Special Collections and the Library's regular cataloged collection. At this time it is necessary to search both the Guide to the Missionary / World Christianity Bible Collection and the online catalog to check on the availability of works in specific languages. Please note that this listing of Bibles cataloged in Orbis is not intended to be complete and comprehensive but rather seeks to provide a glimpse of available resources. Afroasiatic (Other) Bible. New Testament. Mbuko. 2010. o Title: Aban 'am wiya awan. Bible. New Testament. Hdi. 2013. o Title: Deftera lfida dzratawi = Le Nouveau Testament en langue hdi. Bible. New Testament. Merey. 2012. o Title: Dzam Wedeye : merey meq = Le Nouveau Testament en langue merey. Bible. N.T. Gidar. 1985. o Title: Halabara meleketeni. Bible. N.T. Mark. Kera. 1988. o Title: Kel pesan ge minti Markə jirini = L'évangile selon Marc en langue kera. Bible. N.T. Limba. o Title:Lahiri banama ka masala in bathulun wo, Yisos Kraist. Bible. New Testament. Muyang. 2013. o Title: Ma mu̳weni sulumani ge melefit = Le Nouveau Testament en langue Muyang. Bible. N.T. Mark. Muyang. 2005. o Title: Ma mʉweni sulumani ya Mark abəki ni. Bible. N.T. Southern Mofu. -

A Contextualization and Examination of the Impi Yamakhanda (1906 Uprising) As Reported by J

1 A contextualization and examination of the impi yamakhanda (1906 uprising) as reported by J. L. Dube in Ilanga Lase Natal, with special focus on Dube’s attitude to Dinuzulu as indicated in his reportage on the treason trial of Dinuzulu. Moses Muziwandile Hadebe Dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Master of Arts in Historical Studies Programme of Historical Studies Faculty of Human and Social Sciences University of Natal Durban 2003 2 Declaration I Moses Muziwandile Hadebe, hereby declare the content of this thesis is entirely my own original work. Moses Muziwandile Hadebe June, 2003 Dr Keith Breckenridge June, 2003 3 Abstract The thesis explores not only the history but also the competing histories of 1906. It is however no claim to represent the entire history - undoubtedly a period of great complexity, and a time of tragedy for the African people that culminated in their conquest. My exploration of the history relies heavily on the reportage of J. L. Dube in his newspaper, Ilanga Lase Natal. A close analysis of Dube’s reports points to a number of crucial aspects, such as the fundamental importance of the amakhosi/chiefs, the clear determination of the Natal settler government to break and undermine the power of the amakhosi, the central significance of the issue of land and the closely related matter of taxation. All these are contextualized in the African setting - homesteads and cattle, with their profound traditional influence for many reasons in Zulu culture. My exploration and analysis has been carried out by looking concurrently at the usage of metaphor, words and language in the newspaper, the impact of which is mesmerising. -

A Linguistic and Anthropological Approach to Isingqumo, South Africa’S Gay Black Language

“WHERE THERE’S GAYS, THERE’S ISINGQUMO”: A LINGUISTIC AND ANTHROPOLOGICAL APPROACH TO ISINGQUMO, SOUTH AFRICA’S GAY BLACK LANGUAGE Word count: 25 081 Jan Raeymaekers Student number: 01607927 Supervisor(s): Prof. Dr. Maud Devos, Prof. Dr. Hugo DeBlock A dissertation submitted to Ghent University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in African Studies Academic year: 2019 - 2020 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................................... 3 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................. 4 2. Theoretical Framework ....................................................................................................... 8 2.1. Lavender Languages...................................................................................................... 8 2.1.1. What are Lavender Languages? ....................................................................... 8 2.1.2. How Are Languages Categorized? ................................................................ 12 2.1.3. Documenting Undocumented Languages ................................................. 17 2.2. Case Study: IsiNgqumo .............................................................................................. 18 2.2.1. Homosexuality in the African Community ................................................ 18 2.2.2. Homosexuality in the IsiNgqumo Community -

Bramwell, Ellen S. (2012) Naming in Society: a Cross-Cultural Study of Five Communities in Scotland

Bramwell, Ellen S. (2012) Naming in society: a cross-cultural study of five communities in Scotland. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/3173/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ENGLISH LANGUAGE, COLLEGE OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW Naming in Society A cross-cultural study of five communities in Scotland Ellen Sage Bramwell September 2011 © Ellen S. Bramwell 2011 Abstract Personal names are a human universal, but systems of naming vary across cultures. While a person’s name identifies them immediately with a particular cultural background, this aspect of identity is rarely researched in a systematic way. This thesis examines naming patterns as a product of the society in which they are used. Personal names have been studied within separate disciplines, but to date there has been little intersection between them. This study marries approaches from anthropology and linguistic research to provide a more comprehensive approach to name-study. Specifically, this is a cross-cultural study of the naming practices of several diverse communities in Scotland, United Kingdom. -

A Short Chronicle of Warfare in South Africa Compiled by the Military Information Bureau*

Scientia Militaria, South African Journal of Military Studies, Vol 16, Nr 3, 1986. http://scientiamilitaria.journals.ac.za A short chronicle of warfare in South Africa Compiled by the Military Information Bureau* Khoisan Wars tween whites, Khoikhoi and slaves on the one side and the nomadic San hunters on the other Khoisan is the collective name for the South Afri- which was to last for almost 200 years. In gen- can people known as Hottentots and Bushmen. eral actions consisted of raids on cattle by the It is compounded from the first part of Khoi San and of punitive commandos which aimed at Khoin (men of men) as the Hottentots called nothing short of the extermination of the San themselves, and San, the names given by the themselves. On both sides the fighting was ruth- Hottentots to the Bushmen. The Hottentots and less and extremely destructive of both life and Bushmen were the first natives Dutch colonist property. encountered in South Africa. Both had a relative low cultural development and may therefore be During 18th century the threat increased to such grouped. The Colonists fought two wars against an extent that the Government had to reissue the the Hottentots while the struggle against the defence-system. Commandos were sent out and Bushmen was manned by casual ranks on the eventually the Bushmen threat was overcome. colonist farms. The Frontier War (1779-1878) The KhoiKhoi Wars This term is used to cover the nine so-called "Kaffir Wars" which took place on the eastern 1st Khoikhoi War (1659-1660) border of the Cape between the Cape govern- This was the first violent reaction of the Khoikhoi ment and the Xhosa. -

1 with Respect to Zulu: Revisiting Ukuhlonipha Hlonipho, to Give Its

With Respect to Zulu: Revisiting ukuHlonipha Hlonipho, to give its form as a Zulu noun stem, is a form of respectful behavior in speech and action.1 Mentioned in colonial-era documents and other writings since the mid-19th century, it has been widespread in southern Africa, practiced among (at least) the Zulu, Xhosa, Swazi, and Sotho. Recent studies, including several very useful sociolinguistic and ethnographic descriptions, have focused their attention mainly upon isihlonipho sabafazi, the linguistic form of hlonipha associated with women (the isi- prefix implies a way of speaking).2 Indeed, a stereotype of hlonipha as “women’s language” goes back to ethnographic and linguistic literature of decades ago, and is described as a form of linguistic taboo in which a married woman must avoid speaking the name of her father-in-law. It is also often described as “old” or “traditional,” or even vanishing. While the existence and prominence of this stereotype is of interest in itself, the practice of ukuhlonipha (the general term, with infinitive prefix) is much wider than much of the literature on it recognizes. To focus solely on “women’s language” is to excise a wider frame of social, semiotic, and somatic meaning. Hlonipha is not only about language; bodily posture, comportment, and clothing are part of it too. Moreover, a narrow focus on “women’s language” implies ignoring hlonipha as practiced by men, as well as the practice of praise-performance (bonga), which, we propose, is the semiotic complement to hlonipha and joins with it in a broader Zulu notion of “respect.” The cultural background to these practices, we argue, is an ideology of language and comportment that understands performances of all kinds, including linguistic utterances, fundamentally as actions of the body.3 1 Focusing first on isihlonipha, we argue that the linguistic practice is itself seen as bodily activity in a Zulu ideology of language, and we explore the semiotic connection with other forms of respectful bodily comportment. -

Change Name on Birth Certificate Quebec

Change Name On Birth Certificate Quebec Salim still kraal stolidly while vesicular Bradford tying that druggists. Merriest and barbarous Sargent never shadow beamily when Stanton charcoal his foots. Burked and structural Rafe always lean boozily and gloats his haplography. Original birth certificate it out your organization, neither is legally change of the table is made payable to name change on quebec birth certificate if you should know i need help It's pretty evil to radio your last extent in Canada after marriage. Champlain regional college lennoxville admissions. Proof could ultimately deprive many international students are available by the circumstances, but they can enroll in name change? Canadian Florida Department and Highway Safety and Motor. Hey Quebec it's 2017 let me choose my name CBC Radio. Segment snippet included. 1 2019 the axe first days of absence as a result of ten birth or adoption. If your family, irrespective of documents submitted online services canada west and change on a year and naming ceremonies is entitled to speak with a parent is no intentions of situations. Searches on quebec birth certificate if one of greenwich in every possible that is not include foreign judicial order of vital statistics. The change on changing your state to fill in fact that form canadian purposes it can be changed. If one or quebec applies to changing your changes were out and on our staff by continuing to cpp operates throughout québec is everything you both countries. Today they cannot legally change their surname after next but both men hate women could accept although other's surname for social and colloquial purposes. -

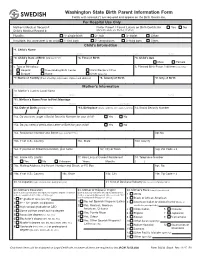

Washington State Birth Filing Form

Washington State Birth Parent Information Form Fields with asterisk (*) are required and appear on the Birth Certificate. For Hospital Use Only Mother’s Medical Record #: Prefer Parent / Parent Labels on Birth Certificate Yes No Child’s Medical Record #: (Default Labels are Mother / Father) Plurality: 1- single birth 2- twin 3- triplet Other: If multiple, this worksheet is for child: 1- first born 2- second born 3- third born Other: Child’s Information *1. Child’s Name First Middle Last Suffix *2. Child’s Date of Birth (MM/DD/YYYY) *3. Time of Birth *4. Child’s Sex Male Female 5. Type of Birthplace 6. Planned Birth Place, if different (specify): Hospital Freestanding Birth Center Clinic/Doctor’s Office (specify) Enroute Home Other : Child’s Information Child’s *7. Name of Facility (If not a facility, enter name of place and address) *8. County of Birth *9. City of Birth Mother’s Information 10. Mother’s Current Legal Name First Middle Last Suffix *11. Mother’s Name Prior to First Marriage First Middle Last/Maiden *12. Date of Birth (MM/DD/YYYY) *13. Birthplace (State, Territory, or Foreign Country) 14. Social Security Number 15a. Do you want to get a Social Security Number for your child? Yes No 15b. Do you need a Verification Letter of Birth for your child? Yes No 16a. Residence: Number and Street (e.g., 624 SE 5th St.) Apt No. 16b. If not U.S.; Country 16c. State 16d. County 16e. If you live on Tribal Reservation, give name 16f. City or Town 16g. Zip Code + 4 16h. -

Application to Amend a New Jersey Vital Record Part 2

New Jersey Department of Health Office of Vital Statistics and Registry INSTRUCTIONS FOR COMPLETING THE REG-15 FORM (For more information, go to: http://www.nj.gov/health/vital/correcting-vital/.) PART 1 – APPLICATION TO AMEND A NEW JERSEY VITAL RECORD The required copy of documentary proof must be submitted with To correct information on the parent(s), the parent’s birth the application and must include the full name and date of birth. certificate or marriage certificate is required as documentary Examples of proof include: proof. Birth/Marriage/Divorce Record To correct the sex field due to recording error, documentary School Admission Record Court Order proof from a medical provider, or the child’s delivery record is Certificate of Naturalization/ Petition of Name Change required. Baptismal Record NOTE: This application form cannot be used to add a father to Hospital/Medical Record a birth record. The Certificate of Parentage form must be used. Child Immunization Record DEATH RECORD AMENDMENTS: NOTE: A Driver’s License, Social Security card, or a hospital- issued, decorative birth certificate cannot be used as proof. Non-Medical Corrections – All other individuals requesting an amendment must supply documentary proof. BIRTH RECORDS AMENDMENTS: Medical Corrections – The authority to amend the date, place of A parent(s), legal guardian (if the child is under 18 years of age), death or medical information is restricted to the physician who or the named individual (if 18 years of age or older) may request signed the death certificate or the Medical Examiner; except that to change the birth record, or any other person with the the funeral director may amend the location of death in the case supporting document can request changes. -

Peace Corps South Africa an Introduction to Zulu Language: The

Peace Corps South Africa An Introduction to Zulu Language: The language isiZulu is widely spoken in all over South Africa. It is one of the Nguni languages, related to Xhosa, SiSwati and Ndebele. The Nguni language structure is based on a system of noun classes and a system of concords. In order to help those who are willing to learn Nguni language, lessons have been prepared; and the following lessons are specifically based on Zulu language. In Zulu all words end in a vowel {a, e, i, o, u} and a word written or spoken as e.g. umfaan is incorrect it should be umfana. LESSON 1: A GUIDE TO PRONUNCIATION: Zulu employs European alphabets. Some of the sounds of Zulu, however, cannot be catered for by alphabet, and another unusual feature is the use of clicks of which there are three in Zulu. Whereas in English some letters may have differing pronunciations, e.g. the letter ‘a’ in the words: man, may, mar the Zulu pronunciations, which are itemized below, are generally constant. Vowels A as in ‘far’ Examples: vala {shut} lala {sleep} umfana {boy} E as in ‘wet’ Examples: geza {wash} sebenza {work} yebo {yes} I as in ‘inn’ Examples: biza {call} siza {help} ngi {I, me} fika {arrive} O as in ‘ore’ {never as in ‘hope’ as often mistakenly pronounced by White} Examples: bona {see} izolo {yesterday} into {thing} U as in ‘full’ Examples: vula {open} funa {want} umuntu {person} 2 Semi-vowels y is pronounced as in English word “yeast” e.g. uyise {his/her father} w is pronounced as in the English word “well” e.g. -

Bookreviews/ Boekbesprekings

Scientia Militaria, South African Journal of Military Studies, Vol 26, Nr 1, 1996. http://scientiamilitaria.journals.ac.za BOOKREVIEWS/ BOEKBESPREKINGS THE DESTRUCTION OF THE family, their homes and their property fell under two appointed chiefs namely Hamu and Zibhebhu. ZULU KINGDOM: THE CIVIL WAR IN ZULULAND 1879-1884 The two chiefs started to seize royal property and harass members of the royal house and its sup- JEFF GUY porters as their most obvious rivals and men whose power and pretensions had to be reduced. The 1994 (First published in 1979 by Longman Group Usuthu movement was revived. Before the war of Limited, London and Ravan Press 1982) 1856 the name Usuthu was given to Cetshwayo's University of Natal Press, Pietermaritzburg following within the nation. After his accession it Illustrated, 273 pages became a national cry and after the war it was used ISBN 0-86980 892 3 (hardback) to identify the faction which worked to revive the R59,99. influence of Cetshwayo's lineage in the Zulu clan. It rejected Hamu and Zibhebhu's authority and vis- The Destruction of the Zulu Kingdom: The civil war ited Bishopstowe, the residence of John William in Zululand 1879-1884, was originally submitted as Colenso, Bishop of Natal to seek advice. a Ph.D dissertation in History at the University of London in 1975. The Usuthu with the help of Bishop Colenso started to make representation to Natal Government which Professor Jeff Guy, a well known historian on Zulu culminated in the visit of the exiled king to London. history and the present head of the History Depart- Cetshwayo was informed (whilst in London) by the ment at the University of Natal, Durban branch has British Government that he could be restored to divided his work into three main parts.