The Transitory Tarot

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tarot De Marseille – Type 2

The International Playing-Card Society PATTERN SHEET 002 Suit System IT Other Classification Recommended name: According to Depaulis (2013) the distinguishing Tarot de Marseille, Type II cards for the Type II of the Tarot de Marseille Alternative name: Tarot of Marseille(s) are: The Fool is called ‘LE MAT’, Trump IIII (Emperor) has no Arabic figure, Trump V History (Pope) has a papal cross, Trump VI (Love): In The Game of Tarot (1980) Michael Dummett Cupid flies from left to right, he has open eyes, has outlined three variant traditions for Tarot in and curly hair, Trump VII (Chariot): the canopy Italy, that differ in the order of the highest is topped with a kind of stage curtain, Trump trumps, and in grouping the virtues together or VIII (Justice): the wings have become the back not. He has called these three traditions A, B, and of the throne, Trump XV (Devil): the Devil’s C. A is centered on Florence and Bologna, B on belly is empty, his wings are smaller, Trump Ferrara, and C on Milan. It is from Milan that the XVI (Tower): the flames go from the Sun to the so-called Tarot de Marseille stems. This standard tower, Trump XVIII (Moon) is seen in profile, pattern seems to have flourished in France in the as a crescent, Trump XXI (World): the central 17th and 18th centuries, perhaps first in Lyon figure is a young naked dancing female, just (not Marseille!), before spreading to large parts dressed with a floating (red) scarf, her breast and of France, Switzerland, and later to Northern hips are rounded, her left leg tucked up. -

The Illustration and the Meanings It Produces

The Illustration and the meanings it produces The loose chains, the satanic symbols, the ugly horned creature squatting on the pedestal, the nude couple with the woman sporting grapes (wine) on her tail and the man’s tail on fire: Rider Waite’s devil is the one of Christian culture. Note that this couple seems to be copied from Adam and Eve in Lovers (by the artwork). Devil, Lovers, and Two of Cups are three Rider Waite Tarot cards that show a couple with a figure above them interfering in their story. In each of these, the figure above is an interfering influence: a malefic (bad, adverse) influence in Devil and Two of Cups, and a (angry?) supervision in Lovers. Is that the angel that evicted them from the Garden? - because the terrain isn’t a garden. Nevertheless, it appears as a guardian angel at times. And in case you’re thinking Hierophant also has the three figures in its illustration: We are talking about a couple (not two male monks). Hierophant’s middle figure, the pope, isn’t interfering in the lives of the monks who also serve in the rituals. The reason I selected ‘bound’ to represent the title to call Devil in the back of your mind is that the chains, of course, are binding or are bonds; but also Devil is all about obligation, being bound to. That concept births most of the positive words for Devil. Yes, there are positive words for Devil! 1 The chains play varied roles in the concepts Devil lends itself to. -

Secret Traditions in the Modern Tarot: Folklore and the Occult Revival

Secret Traditions in the Modern Tarot: Folklore and the Occult Revival I first encountered the evocative images of the tarot, as no doubt many others have done, in T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land. This led to Pamela Coleman Smith’s tarot deck, and from there to the idiosyncratic writings of A.E. Waite with its musings on the Grail, on ‘secret doctrines’ and on the nature of mystical experience. Revival of interest in the tarot and the proliferation of tarot decks attests to the vibrancy of this phenomenon which appeared in the context of the eighteenth century occult revival. The subject is extensive, but my topic for now is the development of the tarot cards as a secret tradition legend in Britain from the late 1880’s to the 1930’s. (1) During this period, ideas about the nature of culture drawn from folklore and anthropological theory combined with ideas about the origins of Arthurian literature and with speculations about the occult nature of the tarot. These factors working together created an esoteric and pseudo-academic legend about the tarot as secret tradition. The most recent scholarly work indicates that tarot cards first appeared in Italy in the fifteenth century, while speculations about their occult meaning formed part of the French occult revival in the late eighteenth century. (Dummett 1980, 1996 ) The most authoritative historian of tarot cards, the philosopher Michael Dummett, is dismissive of occult and divinatory interpretations. Undoubtedly, as this excellent works points out, ideas about the antiquity of tarot cards are dependent on assumptions made at a later period, and there is a tendency among popular books to repeat each other rather than use primary sources. -

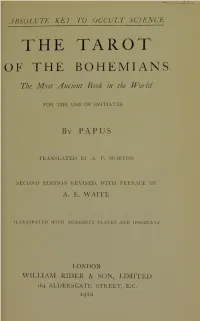

The Tarot of the Bohemians : the Most Ancient Book in the World

IBSOLUTE KET TO OCCULT SCIENCE THE TAROT ÜF THE BOHEMIANS The Most Ancient Book in the World FOR THE USE OF INITIATES By papus TRANSLATED BY A. P. MORTON SECOND EDITION REVISED, WITH PREFACE B Y A. E. WAITE ILLUSTRATED WITH N UMEROU S PLATES AND WOODCUTS LONDON WILLIAM RIDER & SON, LIMITED 164 ALDERSGATE STREET, E.C. 1910 Absolute Key to Oocult Science Frontispicce 2) BVÜ W Wellcome Libraty i forthe Histôry standing Il and ififcteï -, of Medi Printed by Ballantyne, HANSON &* Co. At the Ballantyne Press, Edinburgh PREFACE TO THE ENGLISH TRANSLATION An assumption of some kind being of common con- venience, that the line of least résistance may be pursued thereafter, I will open the présent considéra- tion by assuming that those who are quite unversed in the subject hâve referred to the pages which follow, and hâve thus become aware that the Tarot, on its external of that, side, is the probable progenitor playing-cards ; like these, it has been used for divination and for ail but that behind that is understood by fortune-telling ; this it is held to hâve a higher interest and another quality of importance. On a simple understanding, it is of allegory; it is of symbolism, on a higher plane; and, in fine, it is of se.cret doctrine very curiously veiled. The justification of these views is a different question; I am concerned wit>h ihe statement of fact are and this being said, I can that such views held ; pass to my real business, which" is in part critical and in part also explanatory, though not exactly on the elementary side. -

CALIFORNIA's NORTH COAST: a Literary Watershed: Charting the Publications of the Region's Small Presses and Regional Authors

CALIFORNIA'S NORTH COAST: A Literary Watershed: Charting the Publications of the Region's Small Presses and Regional Authors. A Geographically Arranged Bibliography focused on the Regional Small Presses and Local Authors of the North Coast of California. First Edition, 2010. John Sherlock Rare Books and Special Collections Librarian University of California, Davis. 1 Table of Contents I. NORTH COAST PRESSES. pp. 3 - 90 DEL NORTE COUNTY. CITIES: Crescent City. HUMBOLDT COUNTY. CITIES: Arcata, Bayside, Blue Lake, Carlotta, Cutten, Eureka, Fortuna, Garberville Hoopa, Hydesville, Korbel, McKinleyville, Miranda, Myers Flat., Orick, Petrolia, Redway, Trinidad, Whitethorn. TRINITY COUNTY CITIES: Junction City, Weaverville LAKE COUNTY CITIES: Clearlake, Clearlake Park, Cobb, Kelseyville, Lakeport, Lower Lake, Middleton, Upper Lake, Wilbur Springs MENDOCINO COUNTY CITIES: Albion, Boonville, Calpella, Caspar, Comptche, Covelo, Elk, Fort Bragg, Gualala, Little River, Mendocino, Navarro, Philo, Point Arena, Talmage, Ukiah, Westport, Willits SONOMA COUNTY. CITIES: Bodega Bay, Boyes Hot Springs, Cazadero, Cloverdale, Cotati, Forestville Geyserville, Glen Ellen, Graton, Guerneville, Healdsburg, Kenwood, Korbel, Monte Rio, Penngrove, Petaluma, Rohnert Part, Santa Rosa, Sebastopol, Sonoma Vineburg NAPA COUNTY CITIES: Angwin, Calistoga, Deer Park, Rutherford, St. Helena, Yountville MARIN COUNTY. CITIES: Belvedere, Bolinas, Corte Madera, Fairfax, Greenbrae, Inverness, Kentfield, Larkspur, Marin City, Mill Valley, Novato, Point Reyes, Point Reyes Station, Ross, San Anselmo, San Geronimo, San Quentin, San Rafael, Sausalito, Stinson Beach, Tiburon, Tomales, Woodacre II. NORTH COAST AUTHORS. pp. 91 - 120 -- Alphabetically Arranged 2 I. NORTH COAST PRESSES DEL NORTE COUNTY. CRESCENT CITY. ARTS-IN-CORRECTIONS PROGRAM (Crescent City). The Brief Pelican: Anthology of Prison Writing, 1993. 1992 Pelikanesis: Creative Writing Anthology, 1994. 1994 Virtual Pelican: anthology of writing by inmates from Pelican Bay State Prison. -

DIVINATION SYSTEMS Written by Nicole Yalsovac Additional Sections Contributed by Sean Michael Smith and Christine Breese, D.D

DIVINATION SYSTEMS Written by Nicole Yalsovac Additional sections contributed by Sean Michael Smith and Christine Breese, D.D. Ph.D. Introduction Nichole Yalsovac Prophetic revelation, or Divination, dates back to the earliest known times of human existence. The oldest of all Chinese texts, the I Ching, is a divination system older than recorded history. James Legge says in his translation of I Ching: Book Of Changes (1996), “The desire to seek answers and to predict the future is as old as civilization itself.” Mankind has always had a desire to know what the future holds. Evidence shows that methods of divination, also known as fortune telling, were used by the ancient Egyptians, Chinese, Babylonians and the Sumerians (who resided in what is now Iraq) as early as six‐thousand years ago. Divination was originally a device of royalty and has often been an essential part of religion and medicine. Significant leaders and royalty often employed priests, doctors, soothsayers and astrologers as advisers and consultants on what the future held. Every civilization has held a belief in at least some type of divination. The point of divination in the ancient world was to ascertain the will of the gods. In fact, divination is so called because it is assumed to be a gift of the divine, a gift from the gods. This gift of obtaining knowledge of the unknown uses a wide range of tools and an enormous variety of techniques, as we will see in this course. No matter which method is used, the most imperative aspect is the interpretation and presentation of what is seen. -

OCCULT BOOKS Catalogue No

THOMPSON RARE BOOKS CATALOGUE 45 OCCULT BOOKS Catalogue No. 45. OCCULT BOOKS Folklore, Mythology, Magic, Witchcraft Issued September, 2016, on the occasion of the 30th Anniversary of the Opening of our first Bookshop in Vancouver, BC, September, 1986. Every Item in this catalogue has a direct link to the book on our website, which has secure online ordering for payment using credit cards, PayPal, cheques or Money orders. All Prices are in US Dollars. Postage is extra, at cost. If you wish to view this catalogue directly on our website, go to http://www.thompsonrarebooks.com/shop/thompson/category/Catalogue45.html Thompson Rare Books 5275 Jerow Road Hornby Island, British Columbia Canada V0R 1Z0 Ph: 250-335-1182 Fax: 250-335-2241 Email: [email protected] http://www.ThompsonRareBooks.com Front Cover: Item # 73 Catalogue No. 45 1. ANONYMOUS. COMPENDIUM RARISSIMUM TOTIUS ARTIS MAGICAE SISTEMATISATAE PER CELEBERRIMOS ARTIS HUJUS MAGISTROS. Netherlands: Aeon Sophia Press. 2016. First Aeon Sophia Press Edition. Quarto, publisher's original quarter black leather over grey cloth titled in gilt on front cover, black endpapers. 112 pp, illustrated throughout in full colour. Although unstated, only 20 copies were printed and bound (from correspondence with the publisher). Slight binding flaw (centre pages of the last gathering of pages slightly miss- sewn, a flaw which could be fixed with a spot of glue). A fine copy. ¶ A facsimile of Wellcome MS 1766. In German and Latin. On white, brown and grey-green paper. The title within an ornamental border in wash, with skulls, skeletons and cross-bones. Illustrated with 31 extraordinary water-colour drawings of demons, and three pages of magical and cabbalistic signs and sigils, etc. -

Theosophical Notes No. 6 Winter 2018-19

Volume 2, Issue 2 (6) 17th February 2019 Winter 2018-19 Newsletter 17th February 2019 1 Theosophical Notes No. 6, Winter 2018-19 A home for commentaries & research on the Theosophical Movement There is one thing that should be remembered in the midst of all difficulties, and it is this—“When the lesson is learned, the necessity ceases.” Robert Crosbie, pupil of William Q Judge, ex-President of the Boston Theosophical Society, founder of the United Lodge of Theosophists Please circulate to friends and colleagues who may be interested Quarterly Newsletter from the ULT in London, UK and New York, USA. Winter 2018-19 Newsletter 17th February 2019 2 Editor’s note The aim of these Notes is to give the timeless Perennial Wisdom just as it was when released from its centuries of obscuration, and to show it can help in all departments of life, viz. science, philosophy & religion, or rather psychology. In times of change and difficulty it is natural to seek principles in which we can have confidence; so what can reliably guide us to live wisely and intelligently? Is it to feel a duty to our suffering neighbour? To free ourselves of hypocrisy and injustice? Relieving others of it by example? Reasonable and tolerant debates? A free judiciary and press? Are these not the deep-running strands of social fabric that hold society together on which we ultimately depend? But the inner Path shows these many civil ‘goods’ are consequences of just a few virtues, the paramitas of “The Voice of the Silence.” With them comes the willingness to bravely enter new spaces and deeper ideals, to actively fight for and cultivate balance, patience, and charity and begin a mental renewal. -

Tarot Reading Style: Healer Tarot Reading Style: Healing

Tarot Reading Style: Healer Tarot Reading Style: Healing USING YOUR NATURAL GIFTS & ABILITIES... You help people connect with the core energy of their obstacles and shift them into opportunities. You help them find tools to heal from the pain carried around from past relationships and situations. YOUR GREATEST TOOL IN TAROT READING IS... Resolving Past Issues In your readings, you bring focus and awareness to bringing harmony, balance, and alignment to all levels of being (mind, body, & spirit) and help your clients move through past blocks and baggage. Major Arcana Archetype Temperance Temperance reminds us that real change takes time ,A person's ability to exercise patience, balance, and self-control are infinite virtues. Temperance represents someone who has a patient, harmonious approach to life and understands the value of compromise. A READER WITH THIS ARCHETYPE: ... is able to guide people into a place of healing, where they begin to release the past. Because of their natural gift for diplomacy, they tend to be excellent communicators who bring out the best in their clients and friends. They could be holistic healers or have other psychic abilities and are able to combine different aspects of any modality in order to create something new and fresh. Your Strengths Healing HEALERS HAVE A NATURAL TALENT FOR SEEING 'CAUSE & EFFECT' ... Highlighting Connecting Patterns & Symptoms Limiting to Beliefs Experiences Easily See How It Plays Out In Clients Lives ... You focus on creating balance and harmony in your clients lives. ... You help them move out of the past by helping them revise and reframe it. ... You honor your clients pain and create the space for them to move through it. -

Genii Session 2007-12 Brief Updated History Of

Genii Session By Roberto Giobbi A Brief Updated History of Playing Cards When I published the German version of Card College Volume 1 in 1992, I included a short essay on the history of playing cards. In later editions I expanded on it and made a few corrections, among other smaller things I had committed a bigger mistake, namely that of assuming that today’s playing cards originated from tarot cards. The truth, as so often, is exactly the opposite, because playing cards were already in use in Europe in the second half of the 14th century whereas the game of Tarocchi and with it the Tarot cards was only invented in the first part of the 15th century in Italy. These mistakes were corrected in later editions of Card College and I’m therefore publishing this updated version of my essay for the benefit of all those who have the first few editions (we now have about 19,000 copies of Card College Volume 1 in the market). At the end of the essay I have also added a small annotated bibliography for all who would like to obtain more information about playing cards, their history, use, symbolism etc., a most fascinating subject. Rather than calling playing cards a prop, as it is often done in the literature, I would like to consider them to be an instrument of the card conjurer, like the piano or the violin is an instrument to a musician, and I would even dare saying that cards are the most important and most widely used instrument in all of conjuring. -

Wayward Dark Tarot Book.Pdf

Wayward Dark Tarot “Your vision will become clear only when you can look into your own heart. Who looks outside, dreams; who looks inside, awakes.” -Carl Jung In the imagery of the Wayward Dark Tarot are the archetypes and symbolism of Aleister Crowley’s Thoth Tarot deck, mirrored and modified into a chthonic afterlife evoking the beautiful and the macabre. Familiarity with the Thoth Tarot will give you additional insight (and likely, additional critiques) of the Wayward Dark Tarot. Yet it should read on its own strengths as well. As it may be considered a fun house mirror of the Thoth deck, it is the same for your own inner thoughts and imagination. Look to the cards and you might discover a path to your subconscious paved through the archetypes of the Tarot. “Let the inner god that is in each one of us speak. The temple is your body, and the priest is your heart: it is from here that every awareness must begin.” -Alejandro Jodorowsky There are many ways to use a Tarot Deck. It can be for card games like tarocchini, occult purposes like divination, and in pursuing improvement through self-reflection and self-work. There is no right and wrong way to use your deck, just so long as the way you use it is a way that works for you. This book provides card keywords and meanings for your own clarity. If you have a stronger association with a card that contradicts the meanings given here, then go by your own interpretation. Above all, this book is meant to be a helpful guide, not a dictator. -

Spirit Keeper's Tarot, Marseille, RWS, and Thoth Correspondences

SKT, TDM, RWS, AND THOTH TAROT KEY CORRESPONDENCES (By Standardized Order) Major Arcana 22 Keys Spirit Keeper’s Tarot Tarot de Marseilles Rider-Waite-Smith Thoth (SKT) (TdM) (RWS) 0: The Initiate 0: The Fool 0: The Fool 0: The Fool 0: The Seeker 0: The Keeper 1: The Magus I: The Magician I: The Magician I: The Magus (or The Juggler) (or The Juggler) 2: The Priestess II: The Popess II: The High Priestess II: The Priestess (or The High Priestess) 3: The Empress III: The Empress III: The Empress III: The Empress 4: The Emperor IV: The Emperor IV: The Emperor IV: The Emperor 5: The Holy See V: The Pope V: The Hierophant V: The Hierophant 6: The Lovers VI: The Lovers VI: The Lovers VI: The Lovers (or The Brothers) 7: The Chariot VII: The Chariot VII: The Chariot VII: The Chariot 8: The Force VIII: Justice VIII: Strength VIII: Adjustment [XI: Strength] [XI: Lust] 9: The Erudite IX: The Hermit IX: The Hermit IX: The Hermit 10: Wheel of Life X: The Wheel of X: Wheel of Fortune X: Fortune Fortune 11: The Chancellor XI: Strength XI: Justice XI: Lust [VIII: Justice] [VIII: Adjustment] Page 1 of 12 SKT: TdM, RWS, and Thoth Key Correspondences By Standardized Order Spirit Keeper’s Tarot Tarot de Marseilles Rider-Waite-Smith Thoth (SKT) (TdM) (RWS) 12: The Outlaw XII: The Hanged Man XII: The Hanged Man XII: The Hanged Man 13: The Reaper XIII: Death XIII: Death XIII: Death (Untitled) 14: The Angel XIV: Temperance XIV: Temperance XIV: Art 15: The Demon XV: The Devil XV: The Devil XV: The Devil 16: The Tower XVI: The Tower XVI: The Tower XVI: The Tower