COVID-19 in Developing Economies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ACADEMICS, the *ADAMS, Jerri ALAIMO, Chuck, Quartet *AL & DICK *ALEXANDRIA, Lorez *ALLEN, Joe, & His Alley Cats ANDREWS

DEBUT PEAK B-side Price Label & Number A *ACADEMICS, The White doo-wop vocal group formed in New Haven, Connecticut: Dave Fisher (lead), Billy Greenberg, Marty Gantner, Ronnie Marone and Richie “Goose” Greenberg. Fisher later formed folk group The Highwaymen (1961 hit “Michael”). Fisher died on 5/10/2010 (age 70). Darla, My Darlin’ ...................................................................At My Front Door $300 Ancho 103 THE ACADEMICS featuring Ronnie Marone 1/25/58 5 Loomis Temple Of Music / New Haven, CT *ADAMS, Jerri Born on 5/30/1930 in Cincinnati, Ohio. Female singer. Every Night About This Time 2/22/58 9 1 WTOR / Torrington, CT (Alan Field) My Heart Tells Me................................................................................... Columbia 41111 Ray Ellis (orch., above 2) 3/1/58 2 2 WADK / Newport, RI (Steve May) 3/15/58 4 3 WICE / Providence, RI (Jim Mendes) 3/22/58 6 4 WHIM / Providence, RI (Bob Bassett) ALAIMO, Chuck, Quartet Rockin’ In G .......................................................................Hop In My Jalop [I] MGM 12636 5/31/58 9 WRVM / Rochester, NY (John Holliday) *AL & DICK Prolific songwriting team of Al Hoffman (born on 9/25/1902 in Minsk, Russia; died on 7/21/1960, age 57) and Dick Manning (born on 6/12/1912 in Belarus, Russia; died on 4/11/1991, age 78). Wrote such hits as “Allegheny Moon” and “Hot Diggity.” I’ll Wait..................................................................Junior Miss (With A Senior Kiss) Carlton 452 Jimmy Lytell (orch.) 4/19/58 9 WJWL / Georgetown, DE (Bob Smith) *ALEXANDRIA, Lorez Born Dolorez Alexandria Turner on 8/14/1929 in Chicago, Illinois. Died on 5/22/2001 (age 71). -

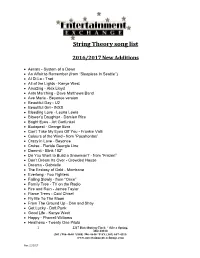

String Theory Song List

String Theory song list 2016/2017 New Additions Aerials - System of a Down An Affair to Remember (from “Sleepless In Seattle”) Al Di La - Trad All of the Lights - Kanye West Amazing - Alex Lloyd Ants Marching - Dave Matthews Band Ave Maria - Beyonce version Beautiful Day - U2 Beautiful Girl - INXS Bleeding Love - Leona Lewis Blower’s Daughter - Damien Rice Bright Eyes - Art Garfunkel Budapest - George Ezra Can’t Take My Eyes Off You - Frankie Valli Colours of the Wind - from “Pocahontas” Crazy in Love - Beyonce Cruise - Florida Georgia Line Dammit - Blink 182* Do You Want to Build a Snowman? - from “Frozen” Don’t Dream Its Over - Crowded House Dreams - Gabrielle The Ecstasy of Gold - Morricone Everlong - Foo Fighters Falling Slowly - from “Once” Family Tree - TV on the Radio Fire and Rain - James Taylor Flame Trees - Cold Chisel Fly Me To The Moon From The Ground Up - Dan and Shay Get Lucky - Daft Punk Good Life - Kanye West Happy - Pharrell Williams Heathens - Twenty One Pilots 1 2217 Distribution Circle * Silver Spring, MD 20910 (301) 986-4640 *(888) 986-4640 *FAX (301) 657-4315 www.entertainmentexchange.com Rev: 11/2017 Here With Me - Dido Hey Soul Sister - Train Hey There Delilah - Plain White T’s High - Lighthouse Family Hoppipola - Sigur Ros Horse To Water - Tall Heights I Choose You - Sara Bareilles I Don’t Wanna Miss a Thing - Aerosmith I Follow Rivers - Lykke Li I Got My Mind Set On You - George Harrison I Was Made For Loving You - Tori Kelly & Ed Sheeran I Will Wait - Mumford & Sons -

12.4 Radio Days Song List

BIG BAND SONG LIST Laughter to raise a nation’s spirits. Music to stir a nation’s soul. Lorie Carpenter-Niska • Sheridan Zuther Kurt Niska • Michael Swedberg • Terrence Niska A Five By Design Production I’ve Got A Gal In Kalamazoo ..........................Mack Gordon & Harry Warren Big Noise From Winnetka .Bob Haggart, Ray Bauduc, Gil Rodin & Bob Crosby I’ll Never Smile Again ..............................................................Ruth Lowe Three Little Fishies .............................................................. Saxie Dowell Mairzy Doats .............................Milton Drake, Al Hoffman & Jerry Livingston Personality ........................................... Jimmy Van Heusen & Johnny Burke Managua Nicaragua ....................................... Albert Gamse & Irving Fields Opus One...................................................................................Sy Oliver Moonlight In Vermont............................... John Blackburn & Karl Seussdorf Juke Box Saturday Night ..................................Al Stillman & Paul McGrane Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy .................................. Don Raye & Hughie Prince INTERMISSION A-Tisket, A-Tasket ...................................... Van Alexander & Ella Fitzgerald Roodle Dee Doo ......................................Jimmy McHugh & Harold Adamson Halo Shampoo .......................................................................... Joe Rines The Trolley Song............................................... Ralph Blane & Hugh Martin Let’s Remember Pearl Harbor -

Sheet Music Collection

McLean County Museum of History Sheet Music Collection Inventoried by Sharon Tallon, Museum Library volunteer German translation by Eleanor Mede April 2012 Collection Information VOLUME OF COLLECTION: Three Boxes COLLECTION DATES: 1870 – 1968 PROVENANCE: None RESTRICTIONS: Collection has several brittle documents. Before making photocopies of items please obtain permission from librarian or archivist. REPRODUCTION RIGHTS: Permission to reproduce or publish material in this collection must be obtained in writing from the McLean County Museum of History. ALTERNATIVE FORMATS: None OTHER FINDING AIDS: None LOCATION: Archives Scope Note This collection includes approximately 750 individual pieces of sheet music, booklets and books copyrighted from 1870 through 1968. A few are encapsulated and may appear in displays in the People or Politics room on the Museum’s first floor. Sheet music also is sometimes featured in temporary, but long-running, displays. People who lived in (or once lived in) McLean County donated most, if not all, of the individual sheets, booklets and books of music that represent the 90 years of music listed in this collection. The first section (Box 1, Folders 1 through 6) is devoted to music that has a direct connection to McLean County. Other sections in Box 1 include music with Chicago connections as well as other places in Illinois, a few other states and Canada, as well as cultural and subject-related music. Dance and instrumental music (with or without vocal) make up the bulk of Box 2 along with a listing and some sheet music by Irving Berlin and Walt Disney. Five folders (10, 11, 15, 16, and 17) are devoted to German instrumental music. -

Jimmy Mchugh Collection of Sheet Music Title

Cal State LA Special Collections & Archives Jimmy McHugh Collection of Sheet Music Title: Jimmy McHugh Collection of Sheet Music Collection Number: 1989.001 Creator: Jimmy McHugh Music Inc Dates: 1894 - 1969 Extent: 8 linear ft. Repository: California State University, Los Angeles, John F. Kennedy Memorial Library, Special Collections and Archives Location: Special Collections & Archives, Palmer, 4th floor Room 4048 - A Provenance: Donated by Lucille Meyers. Processing Information: Processed by Jennifer McCrackan 2017 Arrangement: The collection is organized into three series: I. Musical and Movie Scores; II. Other Scores; III. Doucments; IV: LP Record. Copyright: Jimmy McHugh Musical Scores Collection is the physical property of California State University, Los Angeles, John F. Kennedy Memorial Library, Special Collections and Archives. Preferred Citation: Folder title, Series, Box number, Collection title, followed by Special Collections and Archives, John F. Kennedy Memorial Library, California State University, Los Angeles Historical/Biographical Note Jimmy Francis McHugh was born in Boston, Massachusetts on July 10th, 1893 and is hailed as one of the most popular Irish-American songwriters since Victor Herbert. His father was a plumber and his mother was an accomplished pianist. His career began when he was promoted from a office boy to a rehearsal pianist at the Boston Opera House. As his desire was to write and perform “popular” music, he left the job in 1917 to become a pianist and song plugger in Boston with the Irving Berlin publishing company. In 1921, he moved to New York after getting married and started working for Jack Mills Inc. where he published his first song, Emaline. -

Sidestep-Programm - Gesamt 1 - Nach Titel

Sidestep-Programm - Gesamt 1 - nach Titel Titel Komponist (Interpret) Jahr 24K Magic Bruno Mars, Philip Lawrence, Christopher Brody Brown (Bruno Mars) 2016 500 Miles (I'm Gonna Be) The Proclaimers 1988 After Dark Steve Huffsteter, Tito Larriva (Tito & Tarantula) 1987/1996 Água De Beber Antonio Carlos Jobim, Vincius De Moraes 1963 Ain't Misbehavin' Fats Waller, Harry Brooks, Andy Razaf (Fats Waller, Louis Armstrong, Ella Fitzgerald, et al.) 1929 Ain't Nobody David Wolinski "Hawk" (Chaka Khan & Rufus) 1983 Ain't No Mountain High Enough N.Ashford, V.Simpson (Marvin Gaye & Tammi Terrell, Diana Ross et al.) 1967 Ain't No Sunshine Bill Withers 1971 Ain't She Sweet Milton Ager, Jack Yellen 1927 Alf Theme Song Alf Clausen 1986 All Around the World Lisa Stansfield, Ian Devaney, Andy Morris (Lisa Stansfield) 1989 All I Have To Do Is Dream Felice & Boudleaux Bryant (The Everly Brothers) 1958 All I Need Nicolas Godin, Jean-Benoît Dunckel, Beth Hirsch (Air) 1998 All I Want For Christmas Is You Mariah Carey, Walter Afanasieff (Mariah Carey) 1994 All My Loving John Lennon, Paul McCartney (The Beatles) 1963 All Night Long Lionel Richie 1983 All Of Me Gerald Marks, Seymour Simons 1931 All Of Me (John) John Stephens, Tony Gad (John Legend) 2013 All Shook Up Otis Blackwell (Elivis Presley) 1957 All That She Wants Ace Of Base 1992 All The Things You Are Oscar Hammerstein II, Jerome Kern 1939 All You Need Is Love John Lennon, Paul McCartney (The Beatles) 1967 Alright Jason Kay, Toby Smith, Rob Harris (Jamiroquai) 1996 Altitude 7000 Russian Standard (Valeri -

Biometric Technologies and Freedom of Expression 2021 First Published by ARTICLE 19 in April 2021

When bodies become data: Biometric technologies and freedom of expression 2021 First published by ARTICLE 19 in April 2021 ARTICLE 19 works for a world where all people everywhere can freely express themselves and actively engage in public life without fear of discrimination. We do this by working on two interlocking freedoms, which set the foundation for all our work. The Freedom to Speak concerns everyone’s right to express and disseminate opinions, ideas and information through any means, as well as to disagree from, and question power-holders. The Freedom to Know concerns the right to demand and receive information by powerholders for transparency good governance and sustainable development. When either of these freedoms comes under threat, by the failure of power-holders to adequately protect them, ARTICLE 19 speaks with one voice, through courts of law, through global and regional organisations, and through civil society wherever we are present. ARTICLE 19 Free Word Centre 60 Farringdon Road London EC1R 3GA UK E: [email protected] W: www.article19.org Tw: @article19org Fb: facebook.com/article19org ISBN: 978-1-910793-43-5 © ARTICLE 19, 2021 This work is provided under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial- ShareAlike 2.5 licence. You are free to copy, distribute and display this work and to make derivative works, except for the images which are specifically licensed from other organisations, provided you: 1. give credit to ARTICLE 19 2. do not use this work for commercial purposes 3. distribute any works derived from this publication under a licence identical to this one. To access the full legal text of this licence, please visit: http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/ by-nc-sa/2.5/legalcode. -

Ella Fitzgerald Collection of Sheet Music, 1897-1991

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf2p300477 No online items Ella Fitzgerald collection of sheet music, 1897-1991 Finding aid prepared by Rebecca Bucher, Melissa Haley, Doug Johnson, 2015; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA, 90095-1575 (310) 825-4988 [email protected] ©2002 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Ella Fitzgerald collection of sheet PASC-M 135 1 music, 1897-1991 Title: Ella Fitzgerald collection of sheet music Collection number: PASC-M 135 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical Description: 13.0 linear ft.(32 flat boxes and 1 1/2 document boxes) Date (inclusive): 1897-1991 Abstract: This collection consists of primarily of published sheet music collected by singer Ella Fitzgerald. Physical Location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact the UCLA Library Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. creator: Fitzgerald, Ella Restrictions on Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Open for research. Advance notice required for access. Contact the UCLA Library Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UCLA Library Special Collections. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. It is the responsibility of the researcher to determine who holds the copyright and pursue the copyright owner or his or her heir for permission to publish where The UC Regents do not hold the copyright. -

1 Nikos A. Salingaros CURRICULUM VITAE Professor of Mathematics

Nikos A. Salingaros CURRICULUM VITAE Professor of Mathematics Urbanist and Architectural Theorist Department of Mathematics The University of Texas at San Antonio One UTSA Circle San Antonio, Texas 78249 e-mail: [email protected] 210 458 5546 office http://zeta.math.utsa.edu/~yxk833/vitae.html Education and Training Ph. D. Physics 1978, State University of New York at Stony Brook M. A. Physics 1974, State University of New York at Stony Brook B. Sc. Physics Cum Laude 1971, University of Miami, Coral Gables Collaborated with Christopher Alexander over a twenty-year period editing Alexander’s four-volume book “The Nature of Order” Languages English, French, Greek, Italian, and Spanish. Positions in Academia University of Texas at San Antonio: Assistant Professor of Mathematics 1983-1987; Associate Professor (tenured) 1987-1995; Professor 1995-present University of Texas at San Antonio: Visiting Lecturer in the College of Architecture 2012 Building Beauty Postgraduate Program in Architecture, faculty member, 2018-present University of Delft, Holland, Adjunct Professor of Urbanism, 2005-2008 University of Rome III, Italy, Visiting Professor of Architecture Tecnológico de Monterrey, Santiago de Querétaro, Mexico, Visiting Professor of Urbanism. 1 Architectural and Urban Projects Commercial Center in Doha, Qatar: a $82 million budget, 55,000 m2 project commissioned in a Classical Greco-Roman/Rinascimento style, 2007, by Hadi Simaan & Partners, José Cornelio da Silva, and Nikos A. Salingaros (not built). Included in the 500th Centennial Exhibition “The New Palladians”, inaugurated and organized by the Prince’s Foundation, London, supported by the ICAA, INTBAU, and RIBA, and published as a book. Urban Plazas Project for the City Government of Querétaro, Mexico, 2008. -

Sidestep-Programm - Gesamt 3 - Nach Stilistik

Sidestep-Programm - Gesamt 3 - nach Stilistik Titel Komponist (Interpret) Stil All Shook Up Otis Blackwell (Elivis Presley) Blues&Rock'n'Roll Before You Accuse Me Ellas McDaniel (Bo Diddley; Eric Clapton) Blues&Rock'n'Roll Blue Suede Shoes (1 for the money...) Carl Lee Perkins Blues&Rock'n'Roll Boom Boom John Lee Hooker Blues&Rock'n'Roll Call It Stormy Monday Aaron "T-Bone" Walker Blues&Rock'n'Roll Crazy Little Thing Called Love Freddie Mercury (Queen) Blues&Rock'n'Roll Dirty Boogie, The Brian Setzer (Brian Setzer Orchestra) Blues&Rock'n'Roll Eight Days a Week John Lennon, Paul McCartney (The Beatles) Blues&Rock'n'Roll Erzherzog Johann Jodler (Wo i geh' und Anton Schosser Blues&Rock'n'Roll steh') Everybody Needs Somebody (To Love) Bert Berns, Solomon Burke, Jerry Wexler (Solomon Burke, Blues Brothers, Rolling Stones, et al.) Blues&Rock'n'Roll Folsom Prison Blues Johnny Cash Blues&Rock'n'Roll Great Balls of Fire (bam-bam-bam-bam) Otis Blackwell, Jack Hammer (Jerry Lee Lewis) Blues&Rock'n'Roll Green Onions Booker T. Jones, Steve Cropper, Al Jackson Jr., Lewie Steinberg (Booker T. & the MG's) Blues&Rock'n'Roll Hello Josephine Fats Domino, Dave Bartholomew (Fats Domino) Blues&Rock'n'Roll Hoch vom Dachstein an (Steirische Jakob Dirnböck, Ludwig Carl Seydler Blues&Rock'n'Roll Landeshymne) Hoochie Coochie Man Willie Dixon (Muddy Waters, Eric Clapton, et al.) Blues&Rock'n'Roll Hound Dog Jerry Leiber, Mike Stoller (Big Mama Thornton, Elvis Presley, et al.) Blues&Rock'n'Roll I Just Wanna Make Love to You Willie Dixon (Etta James) Blues&Rock'n'Roll In die Berg bin i gern Trad. -

120765Bk Ella4 16/3/05 8:55 PM Page 8

120765bk Ella4 16/3/05 8:55 PM Page 8 The Naxos Historical labels aim to make available the greatest recordings of the history of recorded music, in the best and truest sound that contemporary technology can provide. To achieve this aim, Naxos has engaged a number of respected restorers who have the dedication, skill and experience to produce restorations that have set new standards in the field of historical recordings. Available in the Naxos Nostalgia & Jazz Legends series … Nostalgia 8.120546 Nostalgia 8.120624 Jazz Legends 8.120714 Jazz Legends 8.120716 Jazz Legends 8.120735 Jazz legends 8.120750 These titles are not available in the USA NAXOS RADIO Over 70 Channels of Classical Music • Jazz, Folk/World, Nostalgia www.naxosradio.com Accessible Anywhere, Anytime • Near-CD Quality 120765bk Ella4 16/3/05 8:55 PM Page 2 ELLA FITZGERALD Vol.4 Personnel Track 1: Johnny McGhee, trumpet; Bill Doggett, Track 10: The Song Spinners (possibly Margaret ‘Ella And Company’ Original Recordings 1943-1951 piano; Bernie Mackay, guitar; Bob Haggart, Johnson, Travis Johnson, Leonard Stokes, Bella bass; Johnny Blowers, drums; The Ink Spots Allen), vocal (Bill Kenny, Charles Fuqua, Deek Watson, Track 11: Aaron Izenhall, trumpet; Louis Ella Fitzgerald’s life story is well-known by jazz successful focus of the music industry. Some Hoppy Jones), vocal aficionados; how she won an amateur contest in pop-leaning singers, like Dinah Shore and Perry Jordan, alto sax, vocal; Eddie Johnson, tenor Track 2: The Ink Spots (Bill Kenny, Charles sax; Bill Davis, piano; Carl Hogan, guitar; 1934 singing “Judy” and “The Object of My Como, thrived in the decade following the end of Fuqua, Deek Watson, Hoppy Jones), vocal Dallas Bartley, bass; Christopher Columbus, Affection” and idolizing vocalist Connie Boswell; the war. -

1 Quaker Times Fall 2016

Quaker Times The Franklin Alumni Newsletter “Bringing Together Friends of Franklin” Vol. 23 Issue 1 Franklin High School Alumni Publication Fall 2016 Hall of Fame Honors Accomplished Alumni In May the Hall of Fame Celebration returned to Franklin. Nearly 150 alumni and friends toured the halls, viewed the new Hall of Fame Display and searched for tiles. And then the celebration began in earnest as guests entered the Commons to celebrate the induction of five alumni into the Franklin Hall of Fame. Students greeted everyone at the door and provided tours of the school. Board members registered guests. A soundtrack featuring the music of Al Hoffman and Kearney Barton – both inductees this year – played in the background along with a slide show featuring all of the inductees. Rhonda Smith Banchero, 91, served as emcee, graciously keeping the program moving. Sara Thompson, ’68, FAA&F President presented the annual report and introduced board members to the crowd. Board members were elected. Ed Almquist Student talent was a highlight featuring music that spotlighted the two musicians honored that night – duo sang an acapella Bibbidi Bobbidi Boo (written by Al Hoffman), followed by a solo performance of Louie Louie (sound engineered by Kearney Barton). But it was the presentation of the inductees that really topped the evening. Those honored were songwriter Al Hoffman ’21, sound engineer Kearney Barton ’49, orthopedist and medical educator Ed Almquist ’54, electric car advocate Steve Lough ’62, and actress Lori Tan Chinn ’66. Al was introduced by his great-nephew Rocky Friedman. (See his comments on page 22).