Supreme Court, Appellate Division First Department

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyrighted Material

15_787434 bindex.qxp 6/13/06 6:45 PM Page 314 INDEX A Alexander McQueen, 108, 140 Aaron Faber, 192–193 Alfred Dunhill, 199 Aaron’s, 289–290 Allan & Suzi, 87 ABC Carpet & Home, 12, 16, 21–22, American Express, 49 105, 108, 244, 249 American Girl Place, 93–94 Abercrombie & Fitch, 167 Amish Market, 173 About.com, 35 Amore Pacific, 117, 238–239 Accessories, 131–135 Amsterdam Avenue, 87 Accommodations, 67–77 Andy’s Chee-Pees, 216 chains, 76–77 An Earnest Cut & Sew, 189–190 dining deals, 57–58 Ann Ahn, 149 four-star, 73 Anna Sui, 137 luxury, 71–73 Anne Fontaine, 155 promotions, 53 The Annex/Hell’s Kitchen Flea Market, promotions and discounts, 69–71 267–268 tax, 70 Ann Taylor, 86, 167 unusual locations, 75–76 Ann Taylor LOFT, 90, 168 Active sportswear, 135–136 Anthropologie, 105, 117 Add, 131 Antiques, 275–278 Adidas, 21, 135 Anya Hindmarch, 184 Adrien Linford, 102, 255 AOL CityGuide New York, 35 Adriennes, 151 The Apartment, 255, 263 Aerosoles, 207 APC, 186–187 AfternoonCOPYRIGHTED tea, 18, 66–67 A Pea In The MATERIAL Pod, 198 Agatha Ruiz de la Prada, 255 Apple Core Hotels, 76 Airport duty-free stores, 55–56 Apple Store, 116, 264 Akris, 139 April Cornell, 22, 88 Alcone Company, 109–110, 224–225 Arcade Auctions, Sotheby’s, 275 314 15_787434 bindex.qxp 6/13/06 6:45 PM Page 315 Index 315 Armani Casa, 245 Barneys Co-Op, 12, 110, 159 Arriving in New York, 44–45 Barneys New York, 160, 198, 199, Ascot Chang, 85, 199 212, 256 A Second Chance, 307 cafe, 63 Atlantic Avenue (Brooklyn), antiques Barneys Warehouse Sale, 110 shops, 277 Barolo, 67 Au Chat Botte, 156–157 Bathroom accessories, 263 Auctions for art and antiques, 269–275 Bauman Rare Books, 147 Auto, 187, 255–256 Beacon’s Closet (Brooklyn), 128 Aveda, 100, 219–220 Beauty products, 218–240 Aveda Institute, 220, 239 bath and body stores, 228–230 Avon Salon & Spa, 220, 239 big names, 219–223 A. -

Chapter One the BEST of NEW YORK

6484-6 Ch01.F 3/25/02 9:06 AM Page 11 Chapter One THE BEST OF NEW YORK I certainly hope that you will be reading every word in this book (and underlining the good parts in pink felt-tip pen), but I under- stand that many people are truly living the New York Minute and are constantly on a mad dash from here to there—unable to spare the time to read this guide from cover to cover. Or, you may have the time to read this entire book, but find all the possibilities overwhelming. It’s also possible that you won’t be overwhelmed by the information in this book, but find that when you actually get to New York City, you get confused just trying to figure out which way is uptown and which is down- town, let alone trying to find a specific shop in NoLita. To combat the above problems, I have created this at-a-glance chapter to help you get started quickly and easily by using these pages as a handy tip sheet. This chapter features some easy- to-locate shops where you can find what you need if you’re short on time. Each store mentioned here is explained in greater depth in later chapters, and there are plenty more shops discussed inside. Addresses in all listings are given with cross streets so that you can find your destination more easily. When taking a taxi, tell the driver the cross streets as soon as you get in the car so there is no confusion. -

Harborside Restaurant Noon–3 P.M., “All You Can Eat” $5.95

Now Shipping the New Treo 650! Panorama is pleased to recommend the new Treo 650 - in our opinion the most useful travel accessory you’ll ever own! We have made special arrangements with the manufacturer to make the Treo 650 available to our readers for the lowest price anywhere. Award-winning PalmOS • organizer and world phone in one. Stay connected with email, WHY DID • messaging and the Internet. YOU COME TO BOSTON? • Organize your entire world with If you came for a quick Calendar, Contacts, Tasks, Memos overview or a theme park and more. ride, then we’re probably not for you. If on the • Listen to MP3’s or use the built in other hand you came for a camera to capture life on the go. FUN FILLED tour to See the Best of Boston, • Connect with Bluetooth® wireless join us aboard the devices. Orange & Green Trolley. Edit Microsoft Word, Excel and • Boston’s most • comprehensive tour, Powerpoint files. fully narrated by our expert tour conductors • Built-in speaker phone and • Boston's most frequent conference calling service, with pick up and drop off at 16 convenient stops • Exclusive stops & * attraction discounts only $319.99 (after rebates) • Free reboarding free expedited delivery Kids Ride FREE* Ride 2nd Day for To take advantage of this special offer, please call us at: Only $10* “The Whites of their 617-338-2000 Eyes” Exhibit or Boston Harbor An exclusive offer from Panorama, The Official Guide to Boston. Cruise Included* 100% MONEY BACK GUARANTEE in association with 617-269-7010 www.historictours.com * Certain restrictions apply. -

To the Nines Index

TO THE NINES INDEX STACKING PLAN 3 FLOORPLANS 4 BUILDING SPECIFICATIONS 8 THE FB EXPERIENCE 9 TRANSIT AND LOCAL AMENITIES 10 SUSTAINABILITY, WELLNESS 11 & RESILIENCY TEAM 12 MESSAGE FROM OWNERSHIP 13 OWNERSHIP 41 - 5,007 RSF & 3,410 RSF 40 - LEASED 39 - LEASED 38 - LEASED 37 - LEASED 30 - 29,812 RSF STACKING PLAN 25 - LEASED 24 - 28,045 RSF 21 - LEASED 19 - LEASE OUT 18 - LEASE OUT 17 - 5,459 RSF 7 - 28,320 RSF 6 - 28,336 RSF CONTIGUOUS 5 - 28,291 RSF 4 - 28,304 RSF BLOCK OF AVAILABLE 10/2020 3 - 28,326 RSF 169,892 RSF 2 - 28,326 RSF* LEASED LEASE OUT AVAILABLE fisherbrothers.com *On market for sublease, could be available direct from Landlord 49TH STREET CORE & SHELL | 28,300 RSF PARK AVENUE PARK 48TH STREET fisherbrothers.com 49TH STREET BREAKOUT OPEN TEAM PANTRY OPEN TEAM COPY OPEN OFFICE | 28,300 RSF IDEATION SPACE ELEC/TEL ELEC ROOM N/A MEN OFFICES 11 UP DN WORKSTATIONS 142 N/A RECEPTION 2 WORK SPACE SEATS OPEN TEAM UP EXECUTIVE OFFICE 2 TOTAL 155 PRIVATE OFFICE 9 DN WORKSTATION (2'-6"X6') 117 PARK AVENUE PARK RECEPTION 2 TOTAL HEADCOUNT 130 CONF. ROOM 3 UP DN J.C. COLLABORATIVE SPACE WOMEN ELEC BREAKOUT ROOMS 6 ROOM BOARD ROOM 1 N/A TEL. CONFERENCE 5 OPEN TEAM SPACE 4 OPEN TEAM BREAKOUT ROOMS 1 LOUNGE ROOM 1 IDEATION SPACE 1 CAFE PHONE PHONE ROOM ROOM OPEN TEAM SPACE 4 MAIL / STORAGE IT ROOM ROOM SUPPORT COPY PHONE ROOMS 6 STOR. LOUNGE CAFE 1 STOR. WELLNESS PHONE PANTRY 1 ROOM ROOM COAT CLOSET 3 COPY AREA 2 IT ROOM 1 MAIL / STORAGE ROOM 1 WELLNESS ROOM 1 STORAGE 2 48TH STREET fisherbrothers.com 5TH FLOOR | FINANCE OFFICE | 08.27.18 902 BROADWAY, NEW YORK, NY 10010, TELE 212 532-9800 FAX 212 889-2180 C:\Users\hgershen\AppData\Local\Temp\AcPublish_3100\2018-06-04_299 Park_5_Test Fits.dwg Plotted: Aug 27, 18 - 4:25pm hgershen © 2018 MKDA, INC. -

Restaurant Guide

GREAT FOOD, GOOD HEARTS. A Guide to New York’s Most Generous Restaurants GREAT FOOD, GOOD HEARTS. A Guide to New York’s Most Generous Restaurants Now serving New York City for more than 25 years, City Harvest (www.cityharvest.org) is the world’s first food rescue organization, dedicated to feeding the city’s hungry men, women, and children. This year, City Harvest will collect 28 million pounds of excess food from all segments of the food industry, including restaurants, grocers, corporate cafeterias, manufacturers, and farms. This food is then delivered free of charge to nearly 600 community food programs throughout New York City using a fleet of trucks and bikes as well as volunteers on foot. Each week, City Harvest helps over 300,000 hungry New Yorkers find their next meal. 2011 EDITION GREAT FOOD, GOOD HEARTS Tyler Florence marco maccioni PhiliP rusKin Foodwork Productions Osteria Del Circo Ruskin International Tony ForTuna nicK mauTone marcus samuelsson CiTy Harvest T Bar Steak & Lounge Mautone Enterprises Red Rooster Penny & PeTer Glazier Tony may chris sanTos The Glazier Group SD26 The Stanton Social alex Guarnaschelli JULIAN MEDINA BenJamin schmerler Food COunCil: Butter Tolache, Yerba Buena, First Press Public Relations Yerba Buena Perry JosePh r. Gurrera ricK smilow Citarella henry meer Institute of Culinary Education City Hall StePhen P. hanson JOHN sTaGe B.R. Guest Restaurants PhiliP meldrum Dinosaur Bar-B-Que Chair CoUnCiL MEMBERS ANDREW CARMELLINI FoodMatch Locanda Verde Kerry heffernan DR. FELICIA sTOLER, eric riPerT michael anThony South Gate Restaurant Pamela & marc murPhy DCN, MS, RD, FACSM Le Bernardin Gramercy Tavern daVid chanG Benchmark Restaurants Momofuku Johnny iuzzini Bill TelePan donaTella arPaia Jean Georges liz neumarK Telepan honorary Chairs Donatella, Kefi, Mia Dona Tom colicchio Great Performances Craft Restaurants riTa JammeT laurenT Tourondel arThur F. -

Grand Central Partnership (GCP) Business Directory

Grand Central Partnership (GCP) Business Directory Business Name Address Industry Group Cibo 767 Second Ave Food & Drink Dor L' Dor 770 Second Ave AA&F Verizon Wireless (Metro Wireless) 300 East 42nd St Misc. Retail Sussex Wines & Spirits 300 East 42nd St Food & Drink Innovation Luggage 300 East 42nd St Misc. Retail Dean's Family Style Restaurant 801 Second Ave Food & Drink Chase 801 Second Ave Financial Services McFadden's Saloon 800 Second Ave Food & Drink Calico Jack's Cantina 800 Second Ave Food & Drink Bar Kuz 925 800 Second Ave Food & Drink UN Plaza Pharmacy 800 Second Ave Misc. Retail Isaac B. Salon 800 Second Ave Pers. & Prof. Services Page 1 of 276 09/30/2021 Grand Central Partnership (GCP) Business Directory Type Telephone Cross Streets Restaurant 212-681-1616 between 41st - 42nd St Women's Apparel between 41st - 42nd St Elec. & Telecom. between 41st - 42nd St Wine & Liquor Store 212-867-5838 between 41st - 42nd St Luggage 212-599-2998 between 41st - 42nd St Restaurant 212-878-9600 between 42nd - 43rd St Full-Service Branch 212-661-7519 between 42nd - 43rd St Restaurant 646-461-6837 between 42nd - 43rd St Bars & Lounges 212-557-4300 between 42nd - 43rd St Bars & Lounges between 42nd - 43rd St Pharmacy between 42nd - 43rd St Hair Salon 212-867-4716 between 42nd - 43rd St Page 2 of 276 09/30/2021 Grand Central Partnership (GCP) Business Directory Community Postcode Borough Latitude Longitude Board 10017 MANHATTAN 40.749262 -73.972628 6 10017 MANHATTAN 40.749311 -73.972567 6 10017 MANHATTAN 40.749413 -73.972275 6 10017 MANHATTAN -

480 PARK AVENUE 1,530 SF for Lease Between Park and Madison Avenues MIDTOWN MANHATTAN | NY 2,000 SF

RETAIL SPACE 480 PARK AVENUE 1,530 SF For Lease Between Park and Madison Avenues MIDTOWN MANHATTAN | NY 2,000 SF SPACE DETAILS LOCATION POSSESSION COMMENTS Between Park and Madison Avenues Immediate Fully built-out retail space with ample frontage across from the Four Seasons Hotel SIZE TERM Visibility from Park and Madison Avenues Ground Floor 1,530 SF Short or long-term FRONTAGE RENT TRANSPORTATION East 58th Street 32 FT Upon request 2019 Ridership Report CEILING HEIGHTS NEIGHBORS Lexington and 59th Street Ground Floor 14 FT Pronovias, Lavo, Tao, Deciem, Balenciaga, Annual 16,760,813 Celine, Montblanc, Amsale Weekday 54,907 STATUS Weekend 51,474 Formerly Tressera Fifth Avenue and 59th Street Annual 4,995,128 Weekday 15,854 Weekend 17,438 GROUND FLOOR 1,530 SF 68’ 32 FT EAST 58TH STREET Paul Morelli EAST 72ND STREET EAST 72ND STREET EAST 72ND STREET EAST 72ND STREET EAST 72ND STREET Nicholas Sporting Peter Elliot Blue Brawer Antiques AVENUE LEXINGTON MADISON AVENUE MADISON Delta Barber Shop THIRD AVENUE THIRD FIFTH AVENUE PARK AVENUE PARK PARK AVENUE PARK Shen NY Womans Mens Lee Anderson The Empire Shoe Repairing Modern State Spa & Nails Tesoro Costume Jewelry L’Art De Vivre Bespoke Brows Lexington News French Sole Art Frame French Sole Kids Gallery 71 VACANT EAST 71ST STREET EAST 71ST STREET EAST 71ST STREET EAST 71ST STREET EAST 71ST STREET Cotelac RX Pharmacy Per Lei Ristorante York Barber Shop Afghan Kebob House Michael Boris Erika Cleaners San Francisco Clothing Studio 34 Hair Salon Next Cleaners Cae Dei Fiori Cae Bacio Henry Miller -

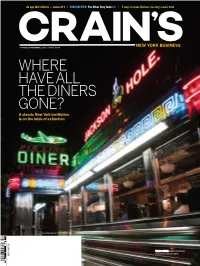

WHERE HAVE ALL the DINERS GONE? a Classic New York Institution Is on the Brink of Extinction

20151026-NEWS--0001-NAT-CCI-CN_-- 10/23/2015 8:44 PM Page 1 An app that delivers ... nurses P. 7 | PARKCHESTER: The Other Stuy Town P. 8 | 5 ways to make Hudson crossings easier P. 12 ® OCTOBER 26-NOVEMBER 1, 2015 | PRICE $3.00 WHERE HAVE ALL THE DINERS GONE? A classic New York institution is on the brink of extinction VOL. XXXI, NO. 43 WWW.CRAINSNEWYORK.COM 43 5 STILL COOKING: Astoria’s Jackson Hole keeps the vibe alive. NEWSPAPER 71486 01068 0 B:11.125” T:10.875” S:10.25” Your business deserves B:14.75” the T:14.5” best S:14” network. Get $300 when you trade in your smartphone and buy any new 4G LTE smartphone. New 2-yr. activation on $34.99+ plan req’d. $300= $200 bill credit + $100 smartphone trade-in credit. findmyrep.vzw.com Offer expires 12/31/15. Offer not available on upgrades. Corporate subscribers only. Bill credits applied within 2-3 billing cycles. Trade-in must be in good working condition. Bill credit will be removed from account if line is suspended or changed to non-qualifying price plan after activation. Activation/upgrade fee/line: $40. IMPORTANT CONSUMER INFORMATION: Subject to Major Acct Agmt, Calling Plan, & credit approval. Up to $350 early termination fee/line. Offers & coverage, varying by svc, not available everywhere; See verizonwireless.com/bestnetwork for details. While supplies last. Restocking fee may apply. © 2015 Verizon. 67392 Project Title: New York Crains Team Proof Approval Job Number New York Crains Inks Side 1 CMYK Full Size (W” X H”) Reduced Size (W” X H”) (Initial and Date) Job Type Ad Inks Side 2 n/a Scale 1” 1” Art Director None Project New York Crains Finishing None Resolution 300 dpi 300 dpi Copywriter None Version Code None Template None Bleed 11.125” x 14.75” 11.125” x 14.75” Studio None 125 E. -

1011-1029 THIRD AVENUE 1,000 - Between East 60Th and 61St Streets 12,000 SF for Lease UPPER EAST SIDE NEW YORK | NY SPACE DETAILS

RETAIL SPACE 1011-1029 THIRD AVENUE 1,000 - Between East 60th and 61st Streets 12,000 SF For Lease UPPER EAST SIDE NEW YORK | NY SPACE DETAILS GROUND FLOOR POSSESSION SPACE E Immediate SPACE D 1,055 SF 192 SF CAFÉ FRESCO RENT FLYWHEEL Upon request SPACE B NEIGHBORS EAST 61ST STREET 61ST EAST 4,800 SF Bloomingdale’s, Bond Vet, Saatva, ZAVO Tempur Pedic, Pure Green, IKEA and CB2 COMMENTS Open to all logical divisions In front of the 59th Street subway EAST 60TH STREET 60TH EAST transportation hub and the iconic Bloomingdale’s flagship Zavo and Café Fresco are both fully vented restaurant opportunities SPACE F 1,207 SF TRANSPORTATION STARBUCKS SPACE A SPACE C 2,345 SF 2019 Ridership Report 818 SF DYLAN’S CANDY BAR Lexington Avenue/ LEARNING APOTHECARY JUICE 59th Street EXPRESS PHARMACY LAND Annual 16,955,204 Weekday 55,608 Weekend 51,768 THIRD AVENUE SPACE E 1,055 SF CAFÉ FRESCO SECOND FLOOR LOWER LEVEL SPACE D 4,482 SF SPACE C SPACE B FLYWHEEL 826 SF 1,690 SF LEARNING ZAVO EXPRESS SPACE B 7,870 SF SPACE A SPACE A ZAVO 2,778 SF DYLAN’S 7,546 SF CANDY BAR DYLAN’S CANDY BAR SPACE DETAILS - SPACE A LOCATION SIZE CEILING HEIGHTS Northeast corner of East 60th Street Ground Floor 2,345 SF Ground Floor 12.5 FT Second Floor 2,778 SF Second Floor 11 FT STATUS Basement 7,546 SF Currently Dylan’s Candy Bar Total 12,669 SF GROUND FLOOR SECOND FLOOR 2,345 SF 2,778 SF THIRD AVENUE LOWER LEVEL 7,546 SF SPACE DETAILS - SPACE B LOCATION SIZE FRONTAGE Between East 60th and 61st Streets Ground Floor 4,800 SF Ground Floor 34 FT on Third Avenue Second Floor 7,870 -

Dining Options

RECOMMENDED DINING OPTIONS BREAKFAST & BEYOND LUNCH, DINNER & COCKTAILS LE PAIN QUOTIDIEN $$ | FAMILY | B | L | D FIG AND OLIVE $$$ | UPSCALE | L | D | C 7 EAST 53RD ST | 0.5 BLOCKS FROM HOTEL 10 EAST 52ND ST | 0.5 BLOCKS FROM HOTEL Belgian style café with take out and sit down service. Upscale restaurant and bar serving seasonal Mediterranean Open Daily 7am-8pm | 646-845-0012 fare prepared with flavored olive oils. Mon–Fri 11am–10pm | Sat–Sun 11:30am | 212-319-2002 BURGER HEAVEN $$ | FAMILY | B | L 9 EAST 53RD ST | 0.5 BLOCKS FROM HOTEL FRESCO $$$ | UPSCALE | L | D | C Serves full American breakfast items plus burgers, fries, soup 34 EAST 52ND ST | 0.5 BLOCKS FROM HOTEL and sandwiches in a quick service diner atmosphere. Popular family-owned Tuscan restaurant serving lasagna, Mon–Fri 6:30am–10:30am | Sat 8am–4pm | Sun 9am–4pm pizza and more in a quaint setting. Mon–Fri 11:30am–11pm | Sat 5pm–11pm | 212-935-3434 FRESCO’S ON THE GO $$ | FAMILY | B | L 40 EAST 52ND ST | 0.5 BLOCKS FROM HOTEL THE MONKEY BAR $$$ | UPSCALE | L | D | C American breakfast counter served with delivery and take-out. 60 EAST 54TH ST | 1.5 BLOCKS FROM HOTEL Open Daily 8:30am–11am Retro murals and swanky furnishings fill this exclusive American eatery with a powerful clientele. EUROPA CAFÉ $ | FAMILY | B | L | D Mon–Fri 11:30am–2am | Sat 5:30pm–2am | 212-308-2950 515 MADISON AVE | 0.5 BLOCKS FROM HOTEL American breakfast deli style to go that serves fresh pastries, eggs, 21 CLUB $$$$ | UPSCALE | L | D | C pancakes, French toast, soups, salads, sandwiches and more. -

Delta Tries to Land New JFK Terminal

20100308-NEWS--0001-NAT-CCI-CN_-- 3/5/2010 8:07 PM Page 1 INSIDE REPORT TOP STORIES SMALL BUSINESS Why eatery startups Gowanus Canal’s are booming. Plus: neighbors should our Restaurateurs dig in for 12 years ® Hall of Fame P. 13 (and counting) of EPA cleanup PAGE 2 VOL. XXVI, NO. 10 WWW.CRAINSNEWYORK.COM MARCH 8-14, 2010 PRICE: $3.00 Wall Street’s M&A machine spewing profits once again Delta tries PAGE 2 to land Hmmm! new JFK terminal Airline in talks to secure $1.5 billion in The divorce math financing for project could soon multiply PAGE 3 BY HILARY POTKEWITZ Your doorman delta air lines’ terminals at John F. Kennedy International Airport rank expects a raise among the dingiest, most cramped fa- PAGE 2 cilities in the area—JFK’s “disasters,” according to one local official. After nearly a decade of on-again, off-again plans to demolish the 1960s relics and start anew, Delta is trying again. The airline is in talks with the Port Authority of New York & New Jersey, which owns New York’s airports, about moving forward with a new terminal, according to sources close to the nego- RICHARD RAVITCH: tiations. Delta hopes to secure $1.5 bil- Fixing the state’s lion in financing for the project. Given budget mess will be the Port Authority’s capital budget his No. 1 mission. constraints—it’s embroiled in a multi- BUSINESS LIVES billion-dollar project to rebuild the World Trade Center site—the state GOTHAM GIGS See DELTA on Page 22 This teacher doesn’t zuma pull his punches P. -

Nycfoodinspectionmyview Based on DOHMH New York City Restaurant Inspection Results

NYCFoodInspectionMyView Based on DOHMH New York City Restaurant Inspection Results DBA BORO PHONE NOODLE HOUSE Queens 7188198205 TACO BELL Brooklyn 8605182577 TACO BELL Brooklyn 8605182577 DUNKIN Queens 5167923957 THE BAGEL FACTORY Brooklyn 7187688300 GEE WHIZ Manhattan 2126087200 NEW DOUBLE CHINESE RESTAURANT Queens 7183263661 GYRO EXPRESS Queens 7182781230 QUIJOTE Queens 9293076007 THE INKAN Queens 7184334171 THE INKAN Queens 7184334171 DIG INN Manhattan 2123655060 DIG INN Manhattan 2123655060 ELSA LA REINA DEL CHICHARRON Manhattan 2123041070 EMERALD FORTUNE Brooklyn 7187879517 EMPELLON Manhattan 2128589365 SOUVLAKI GR MIDTOWN Manhattan 2129747482 EL ALTO DELI MEXICAN FOOD Queens 7184561044 BLUESTONE LANE COFFEE Manhattan 2128888848 GOOD JOY Brooklyn 7188588899 Page 1 of 478 09/30/2021 NYCFoodInspectionMyView Based on DOHMH New York City Restaurant Inspection Results GRADE A A A A A A A A A A A A A A A A A A A A Page 2 of 478 09/30/2021 NYCFoodInspectionMyView Based on DOHMH New York City Restaurant Inspection Results FRESH KITCHEN Manhattan 2124813500 BARROW STREET ALE HOUSE Manhattan 2126910282 DUNKIN Bronx 6468724159 DOMINO'S Manhattan 2125010200 MILE 17 Manhattan 2127721734 BLAGGARD'S PUB Manhattan 2123822611 BROOKDALE Manhattan 2127912500 PATISSERIE DES AMBASSADES Manhattan 2126660078 BY CHLOE Manhattan 6463584021 YUAN BAO 50 Brooklyn 7184371888 SAKE BAR SATSKO Manhattan 2126140933 HAAGEN-DAZS Queens 3477329954 2 PALMITAS MEXICAN DELI Queens 7188491108 FRANK PIZZERIA Brooklyn 3474350000 NEW GOLDEN CHOPSTICKS Manhattan 2128250314