THE Pimi'o MUSIC of DAVID W. GUION Ao'idthe INTERSECTION

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ARSC Journal, Vol

WILLIE ROBYN: A RECORDING ARTIST IN THE 19205 (PART 2) By Tim Brooks Victor to Cameo The early 1920s must have been a heady time for young Robyn, with an exclusive Victor contract, a burgeoning stage and radio career, excellent reviews for his concert work, and talk of the Met. But by 1923 he had hit a plateau. The first setback was the loss ofhis agent, the enthusiastic Hugo Boucek. Boucek had run up large bills publicizing his artists. The economic depression of 1921-22 cut into concert revenues, and many concerts were canceled outright. Deeply in debt, Boucek skipped town, never to be heard from again. Left in the lurch, Robyn did not secure another agent, a move he later felt was a mistake. "I was the most mismanaged person that ever lived," he ruefully explained. The first matter he had to deal with was the expiration of his three-year Victor contract, in mid-1923. Victor was happy to renew, but for the same $7,000 per year as the previous term, and with Robyn still pretty much limited to the foreign series. Robyn insisted on more money, and another chance at popular recording. He made a new popular trial, "Dearest," on April 11th with Nat Shilkret accompanying on piano. Robyn scouted around for other options, and even made a test for Edison on May 24th. The test was reviewed by Thomas Edison himself, who noted of Robyn, 1 Has loud tremolo. Sings too loud. Ifsang less loud he would be much better and have less tremolo. He might do with proper songs. -

The Johnsonian November 7, 1941

Winthrop University Digital Commons @ Winthrop University The oJ hnsonian 1940-1949 The oJ hnsonian 11-7-1941 The ohnsoniJ an November 7, 1941 Winthrop University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.winthrop.edu/thejohnsonian1940s Recommended Citation Winthrop University, "The oJ hnsonian November 7, 1941" (1941). The Johnsonian 1940-1949. 25. https://digitalcommons.winthrop.edu/thejohnsonian1940s/25 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the The oJ hnsonian at Digital Commons @ Winthrop University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The oJ hnsonian 1940-1949 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Winthrop University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. OUR CREED: ! v TODAY'S SERMON The Johnsonian wants to deserve a rep- utation for accuracy, thoroughness, and fairness in the covering of the Winthrop Thanksgiving's Coming, But So Arc campus. You will do us a favor to call our attention to any failure in measuring up to Those Little BLUE Things! •ny of these fundamentals or good news- papering. oman P. S. We Hope Not THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF WINTHROP COLLEGE VOLUME XIX ROCK HILL, SOUTH CAROLINA, NOVEMBER 7, 1MI On Their Way To The Inauguration ?. C. Budget Fall Music Festival m Group Gets Friday; Concert In College Plea Auditorium Sunday Winthrop Asks For More Money to Off- Dr. John F. Williamson Will Conduct Clinics set Price Advances, For 30 Music Teachers—400 High School Buy Pipe Organ. Students Expected on Campus for Event— Rock Hill Choral Cluh to Participate in Clos- A 10 per cent salary in- ;rease for staff members and ing Event. -

Philharmonic Au Dito R 1 U M

LUBOSHUTZ and NEMENOFF April 4, 1948 DRAPER and ADLER April 10, 1948 ARTUR RUBINSTEIN April 27, 1948 MENUHIN April 29, 1948 NELSON EDDY May 1, 1948 PHILHARMONIC AU DITO R 1 U M VOL. XLIV TENTH ISSUE Nos. 68 to 72 RUDOLF f No S® Beethoven: S°"^„passionala") Minor, Op. S’ ’e( MM.71l -SSsr0*“” « >"c Beethoven. h6tique") B1DÛ SAYÂO o»a>a°;'h"!™ »no. Celeb'“’ed °P” CoW»b» _ ------------------------- RUOOtf bKch . St«» --------------THE pWUde'Pw»®rc’^®®?ra Iren* W°s’ „„a olh.r,„. sr.oi «■ o'--d s,°3"' RUDOLF SERKIN >. among the scores of great artists who choose to record exclusively for COLUMBIA RECORDS Page One 1948 MEET THE ARTISTS 1949 /leJ'Uj.m&n, DeLuxe Selective Course Your Choice of 12 out of 18 $10 - $17 - $22 - $27 plus Tax (Subject to Change) HOROWITZ DEC. 7 HEIFETZ JAN. 11 SPECIAL EVENT SPECIAL EVENT 1. ORICINAL DON COSSACK CHORUS & DANCERS, Jaroff, Director Tues. Nov. 1 6 2. ICOR CORIN, A Baritone with a thrilling voice and dynamic personality . Tues. Nov. 23 3. To be Announced Later 4. PATRICE MUNSEL......................................................................................................... Tues. Jan. IS Will again enchant us-by her beautiful voice and great personal charm. 5. MIKLOS GAFNI, Sensational Hungarian Tenor...................................................... Tues. Jan. 25 6. To be Announced Later 7. ROBERT CASADESUS, Master Pianist . Always a “Must”...............................Tues. Feb. 8 8. BLANCHE THEBOM, Voice . Beauty . Personality....................................Tues. Feb. 15 9. MARIAN ANDERSON, America’s Greatest Contralto................................. Sun. Mat. Feb. 27 10. RUDOLF FIRKUSNY..................................................................................................Tues. March 1 Whose most sensational success on Feb. 29 last, seated him firmly, according to verdict of audience and critics alike, among the few Master Pianists now living. -

ARS Audiotape Collection ARS.0070

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8f769x2 No online items Guide to the ARS Audiotape Collection ARS.0070 Franz Kunst Archive of Recorded Sound 2012 [email protected] URL: http://library.stanford.edu/ars Guide to the ARS Audiotape ARS.0070 1 Collection ARS.0070 Language of Material: Multiple languages Contributing Institution: Archive of Recorded Sound Title: ARS Audiotape Collection Identifier/Call Number: ARS.0070 Physical Description: 15 box(es): 419 open reel tapes, 15 audiocassettes, 60 videocassettes Date (inclusive): 1900-1991 Stanford Archive of Recorded Sound Stanford University Libraries Stanford, California 94305-3076 Material Specific Details: 3" reels-5 4" reels-1 5" reels-37 7" reels-334 10.5" reels-40 1/2" tapes on 10" reels - 4 audiocassettes-15 video reels-2 videocassette (VHS)- 59 videocassette (Beta) - 1 Abstract: Miscellaneous tape recordings, mostly small donations, that span the history of the Archive of Recorded Sound. Access Open for research; material must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Contact the Archive for assistance. Publication Rights Property rights reside with repository. Publication and reproduction rights reside with the creators or their heirs. To obtain permission to publish or reproduce, please contact the Head Librarian of the Archive of Recorded Sound. Preferred Citation ARS Audio Miscellany, ARS-0070. Courtesy of the Stanford Archive of Recorded Sound, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, Calif. Sponsor This finding aid was produced with generous financial support from the National Historical Publications and Records Commission. Arrangement Most recordings are described under the series marked "Miscellaneous" according to format and reel size. -

Southwestern News

SOUTHWESTERN NEWS Summer 1973 SOUTHWESTERN NEWS is published quarterly by Southwestern At Memphis, 2000 N. Parkway, Memphis, Tenn. 38112. Second class postage paid at Memphis, Tenn. Volume 36 • Number 3 • June, 1973. Editor - Jeannette Birge. James H. Daughdrill, Jr. Presiding over Progress HWhat we're about is the education of people, not just the teaching of subjects!' Choosing a new president is probably the most crucial de changed just as much as your business. All administration cision a college community is ever called upon to make. has changed - from Theory X to Theory Y if you read Peter The qualifications are high, the requirements exacting. A Drucker. Just as Ford Motor Company is no longer run in president can set a pace and tone that invigorate an the style of Mr. Henry Ford, Sr., so academic administration entire institution, for administrative leadership is essential has changed. Leadership today is more inclusive and to the health and well-being of every college and university. shared. And I'm glad that you are part of that at South On January 30, President James H. Daughdrill, Jr. western. It is not only less lonesome, it is much more ef became President of Southwestern. His remarks to the fective. President's Council last month point up clearly how well II. New Management Style. Besides just the presidency, the selection committees carried out their responsibility: our management team is working under new concepts: new attitudes, communications, and objectives. But first, what is good management? It is that intangible momentum, that I appreciate your being here, your being friends of direction, that hard-to-define leadership quality .. -

THE NAFF COLLECTION (Location: Range 4, Section 5 – NR Workroom)

THE NAFF COLLECTION (Location: Range 4, Section 5 – NR Workroom) The Naff Collection is an accumulation of programs, autographed photographs, posters, folders, booklets, announcements and a few other items which tell the story of professional theater in Nashville between the years 1900 and 1960. This material was collected by the late Mrs. L. C. Naff during the period in which she served as secretary to the Rice Bureau and later as manager of the Ryman Auditorium. She bequeathed the collection to Francis Robinson, assistant manager of the Metropolitan Opera, who began his career as an usher at the Ryman. On March 27, 1967, Mr. Robinson made the formal presentation of the collection to the Public Library of Nashville and Davidson County, Charles C. Trabue, chairman of the board, and Marshall Stewart, chief librarian. The public was invited to this ceremony at which the collection was on display. The materials had been listed by chronological periods and arranged by Ann Dorsey, head of the reference department, Edward Durham and Terry Hudson. After the material had remained on exhibit for one month, it was packed for storage. In January 1971, it was decided that the collection should be classified and indexed so that it might be more readily available to researchers and other interested parties. The holdings in the Naff Collection have been classified as follows: NAFF COLLECTION CLASSIFICATIONS Advertising Announcements Descriptive Folders Letters and Telegrams Librettos Newspaper Clippings Photographs Posters Programs: Concerts Dances Lectures Miscellaneous Musical Comedies Operas Operettas Orchestras Plays Recitals Souvenirs Variety Realia Scripts Souvenir Booklets The subject headings of the various collections will most likely lead to desired information, particularly if the medium of a performer is known. -

International Harvester

INTERNATIONAL HARVESTER '"^"'^'^<^,^,_ A Winter Poem BY KARL C. BRANDNER VOL. 37 NO. 19 AT EVANSVILLE DNION STATION AT LOUISVILLE WORKS The branch managers come in to review progress and plans They visit the new factories and new school, and see advance models of new products EARLY IN FEBRUARY 1944—the year day was spent at Melrose Park Works, that was to prove the greatest in the near Chicago, where a tour of the plant, Harvester Company's production of war meetings, luncheon, and attendance at materiel — the management personnel exhibits of the plant's products preceded from all the Company's sales branches the "Harvester Plans for the Future" were called in to Chicago for a week to official dinner in the evening at the Drake see at first hand some of the wartime Hotel, Chicago. Wednesday night the production, and to hear of the Com delegation boarded two special trains for pany's plans for the postwar period, in Evansville, Indiana, where they were the sofar as those plans could be made in the guests of the Evansville Works through midst of war. They also saw some of the out Thursday and Thursday evening. engineering developments for postwar. Thursday night the two trains took the A sequel to that conference, and management group directly to the doors complementing it, was the Branch Man of the Louisville Works, Louisville, Ken agement Conference during the week of tucky, for a day and evening as guests of last October 6, held in Chicago and at that plant. Friday's events concluded three of the Company's new operations— the week's program, with the managers Melrose Park Works, Evansville Works, and others either departing for their and Louisville Works. -

James Melton: the Tenor of His Times Online

uHbL5 (Mobile ebook) James Melton: The Tenor of His Times Online [uHbL5.ebook] James Melton: The Tenor of His Times Pdf Free Margo Melton Nutt audiobook | *ebooks | Download PDF | ePub | DOC Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #1854156 in Books 2013-04-12Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 9.00 x .61 x 6.00l, .80 #File Name: 1482391449268 pages | File size: 59.Mb Margo Melton Nutt : James Melton: The Tenor of His Times before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised James Melton: The Tenor of His Times: 7 of 7 people found the following review helpful. An excellent, balanced view of an enormous but flawed talentBy Eleanor DuganWhy do people write biographies? Most authors come to the task with such a strong bias, positive or negative, that intelligent readers must seek out several other bios before they can begin to grasp the real person behind the words.This is NOT the case with James Melton: The Tenor of His Times. Margo Melton Nutt has drawn such a clear, believable portrait of her enormously talented, but deeply flawed father, that this book should stand for a long time as the definitive bio of the famous tenor. From youth to his final days, James Melton had the enormous ego essential for survival in the crushing world of professional performers, but, as she shows, this same unrelenting optimism also contributed to his ultimate downfall. His highs and lows were so extreme that, although Nutt never says so, he may even have had bipolar disorder, a disease only recently recognized.For the necessary raves about Melton's stellar career successes and many personal virtues, Nutt draws on her mother's unpublished adoring biography. -

American Heritage Center

UNIVERSITY OF WYOMING AMERICAN HERITAGE CENTER GUIDE TO ENTERTAINMENT INDUSTRY RESOURCES Child actress Mary Jane Irving with Bessie Barriscale and Ben Alexander in the 1918 silent film Heart of Rachel. Mary Jane Irving papers, American Heritage Center. Compiled by D. Claudia Thompson and Shaun A. Hayes 2009 PREFACE When the University of Wyoming began collecting the papers of national entertainment figures in the 1970s, it was one of only a handful of repositories actively engaged in the field. Business and industry, science, family history, even print literature were all recognized as legitimate fields of study while prejudice remained against mere entertainment as a source of scholarship. There are two arguments to be made against this narrow vision. In the first place, entertainment is very much an industry. It employs thousands. It requires vast capital expenditure, and it lives or dies on profit. In the second place, popular culture is more universal than any other field. Each individual’s experience is unique, but one common thread running throughout humanity is the desire to be taken out of ourselves, to share with our neighbors some story of humor or adventure. This is the basis for entertainment. The Entertainment Industry collections at the American Heritage Center focus on the twentieth century. During the twentieth century, entertainment in the United States changed radically due to advances in communications technology. The development of radio made it possible for the first time for people on both coasts to listen to a performance simultaneously. The delivery of entertainment thus became immensely cheaper and, at the same time, the fame of individual performers grew. -

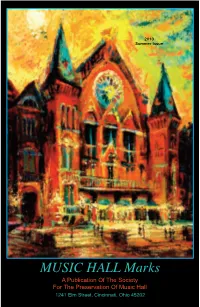

MUSIC HALL Marks MUSIC HALL Marks 2 Very Pleased to Read the Comments Input

2010 Summer Issue MUSICA Publication HALL Of The Society Marks For The Preservation Of Music Hall 1241 Elm Street, Cincinnati, Ohio 45202 1 MUSIC HALL Marks MUSIC HALL Marks 2 very pleased to read the comments input. My thanks go out to all of the selected design firm as they SPMH members, whose personal AsSPMH the new President - President0s of same stately Message Hall. stressed the very historic goals that efforts and financial contributions SPMH, I send you my personal Ever since the time of the SPMH has always embraced. allow us to continue to follow our thanks for your confidence in my original construction, Music Hall There are many challenges ahead mission in supporting Music Hall. selection. I am very pleased to be has undergone a long series of but we believe that substantial ben- I encourage you to mark associated with SPMH and I necessary changes and, SPMH efits will reward substantial efforts. September 20th on your calendars pledge to endeavor along with will continue to play a mean- I wish to pay tribute to as we are planning quite a program the dedicated Board of Di- ingful role in the current Norma Petersen for her ever-pre- for our Annual Meeting! An impor- rectors and members, to Revitalization planning sent leadership and acknowledge tant update on the Revitalization fulfill the Mission of the and implementation. her role in preserving, growing and Plan will be presented and, as cus- Society. Several of our Board enhancing SPMH. She will con- tomary, we shall have delightful en- I’ve already Directors were mem- tinue to play an active part in tertainment, savory cuisine and the found that, as usual, ex- bers of the original SPMH and the organization will great company of friends! citing and rewarding ‘Working Group’, which benefit from her knowledgeable - Don Siekmann events are taking place included representa- in and around this historic tives of the Cincinnati icon we know as Music Don Siekmann Arts Association, the 2010 SPMH Board Hall. -

3N Iwemoriam Enskjold, Ferruccio Tagliavini, Giu JOHN H

PAGE FOUR T irotofit NEWS NOVEMBER 25, 1953 re Voice Of Firestone Has 25th Anniversary Coming Events | (Continued From Page 1) An instructors class in bridge playing started Monday, Novem s a cu ber 23rd, at the Girls’ Club. The Mr. and Mrs. Wilson L. Bradley, Richard Crooks, Margaret Speaks, class will meet alternate Mondays Jr., announce the birth of a son on Lily Pons, Nelson Eddy, Lawrence for a total of four meetings. After November 12, at the Gaston Me Tibbett, Eleanor Steber, Christo the completion of this instructors morial Hospital. Mr. Bradley is pher Lynch, Lauritz Melchior, course, a bridge club open to all the son of Mrs. Gertrude Bradley, Gladys Swarthout, Rise Stevens, employees will be organized. reclaimer, and Bill Bradley. Oscar Levant, Jussi Bjoerling, Mr. and Mrs. George Pender Martha Lipton, Nadine Conner, Basketball practice is being held grass announce the birth of twins, Thomas L. Thomas, Mimi Benzell, each Monday, Tuesday, and Wed Terry and Perry on October 10th, Roberta Peters, Jane Froman, nesday at 4 p. m., in the Gastonia at the Gaston County Negro Hos Jesus Sanroma. Armory. Employees and employees’ pital. Mr. Pendergrass works in Dorothy Maynor, Todd Duncan, children are invited to participate. the Shipping Department. Eugene Conley, Jerome Hines, Pat Full information concerning bas rice Munsel, Vivian Della Chiesa, ketball league play, which starts Leonard Warren, Helen Traubel, soon, may be obtained from Rec Jeanette MacDonald, Dorothy War- reation Director Ralph Johnson. 3n iWemoriam enskjold, Ferruccio Tagliavini, Giu JOHN H. HYDE seppe Valdengo, Frank Guarrera, Bingo is back, and popular as Mr. -

![1951-03-16, [P ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1837/1951-03-16-p-6221837.webp)

1951-03-16, [P ]

i<?0l .J I H.nL^ .yi,br ■ OIHO’ .WH30M10 YTMU03 WSCtAM * jitW-nn Hlfl * X>?, 3<»A'< - ■• - . - rv^s>. •, xt'I’tfTf'-S’iXi/'' .4 *:rr Friday, March <1601951 : VJ-*’, 4 ;> K<;r:; THE SEMI-WEEKLY MADISON COUNTY DEMOCRAT, LONDON, OHM*‘" .................. ,,, /,, '„ ,?l„"'.„z„ .xr; PAGE SEVEN w »v •-» ■ • g i '-1 : ‘ r t “~ i wiH *be ♦‘needed, -provisions have* Campbell, Roger Claris . Jeanne to be made for building up re- Click. Stephen Dowler, Thelma SOCIETY NEWS Straws Leading Spring’s Hat Parade serves ds well as supplies to meet Fichum, -Nancy Gammel!, JUnda MRS. CLUXTON PRESENT® artists of the day. most of whom current needs. O Britn, Beatrice (Rte, iJanet OUTSTANDING PROGRAM are American trained. It should not be overlooked Rinehart. FOR D.A.R. Popular music, .expressive of that good pastures may do as Grade 6— Shirley Davis, Hat Guest Day was observed by our complex life and turbulent Versatile Bonnets Are Topped With Fruit much to give the nation tne need tie Franch, Nancy Lewis, Kay London Chapter, Daughters of the times, has attained a higher stand ed production of livestock as land Me; er, Barbara Price, Charlotte American Revolution, with a ing due to the skill and efforts in feed grain. Renick. musical program for the March of modem composers, but it is BY BDNA MILES Farmers should keep in mind Grade Rhelda Clark, Martha meeting Wednesday afternoon at doubtful if much of it will stand that grasses and legumes are soil Otte, Patricia Ridenoufc the Coovcr Memorial Club House. the test of the ages. -A A BASICALLY simple straw hat that can team up with building crops.