Burma's Political Prisoners and U.S. Sanctions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Statement by His Excellency U Thein Sein President Of

YA A / I CHECK AGAINST DELIVERY STATEMENT BY HIS EXCELLENCY U THEIN SEIN PRESIDENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR AND CHAIRMAN OF THE MYANMAR DELEGATION AT THE GENERAL DEBATE OF THE SIXTY-SEVENTH SESSION OF THE UNITED NATIONS GENERAL ASSEMBLY (New York, 27 September 2012) PERMANENT MISSION OF THE REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR TO THE UNITED NATIONS 10 E. 77TM STREET, NEW YORK, N.Y. 10075 * TEL. (212) 744-1271 • FAX (212) 744-!290 Mr. President, Mr. Secretary-General of the United Nations, Distinguished Delegates, First and foremost, I would like to congratulate you on your well-deserved election as the President of the 67th session of the United Nations General Assembly. Your country, Serbia, and Myanmar has traditionally enjoyed the close friendship and cooperation. Under your able leadership, the General Assembly will make deliberations on measures to address the challenges being faced by the world today. I am confident that your vast wisdom, rich experiences and high diplomatic skills would guide our deliberations to produce desired outcomes. I would also like to take this opportunity to extend our sincere thanks and appreciation to your predecessor, H. E. Mr. Nassir Abdulaziz A1-Nasser, for his outstanding leadership at the 66th session. Mr. President, Myanmar consistently pursues an independent and active foreign policy. One of the basic tenets of our foreign policy is to actively contribute towards the maintenance of international peace and security. In so doing, we encourage efforts to settle differences among nations by peaceful and amicable means. This position of ours matches well with the essence of one of the high-level themes of the current session, namely, "Settlement of disputes by Peaceful Coordination or Means". -

Executive Summary

From: OECD Investment Policy Reviews: Myanmar 2014 Access the complete publication at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264206441-en Executive summary Please cite this chapter as: OECD (2014), “Executive summary”, in OECD Investment Policy Reviews: Myanmar 2014, OECD Publishing. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264206441-4-en This work is published on the responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD. The opinions expressed and arguments employed herein do not necessarily reflect the official views of the Organisation or of the governments of its member countries. This document and any map included herein are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. OECD Investment Policy Reviews: Myanmar 2014 © OECD 2014 Executive summary After years of economic isolation, the government of Myanmar has initiated a wide range of reforms to open its economy to foreign trade and investment. As set out in the Framework for Economic and Social Reform, the reform programme includes: budgetary and tax reforms; monetary and financial sector reforms; liberalisation of trade and investment; food security and agricultural growth; land issues; and improvements in infrastructure availability and quality. The country stands to benefit from greater global and regional economic integration, with its rich natural resources base, young labour force and strategic geographic location between India and China. Bringing about simultaneously a political and economic transition will not be an easy task. In the early 1960s, Myanmar was one of Asia’s leading economies but fell substantially behind many of its peers in ASEAN during the lost decades of military rule. -

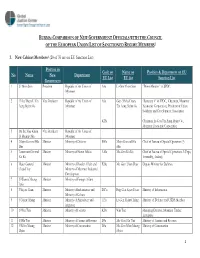

28 of 35 Are on EU Sanction List)

BURMA: COMPARISON OF NEW GOVERNMENT OFFICIALS WITH THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION LIST OF SANCTIONED REGIME MEMBERS1 1. New Cabinet Members2 (28 of 35 are on EU Sanction List) Position in Code on Name on Position & Department on EU No Name New Department EU List EU list Sanction List Government 1 U Thein Sein President Republic of the Union of A4a Lt-Gen Thein Sein “Prime Minister” of SPDC Myanmar 2 Thiha Thura U Tin Vice President Republic of the Union of A5a Gen (Thiha Thura) “Secretary 1” of SPDC, Chairman, Myanmar Aung Myint Oo Myanmar Tin Aung Myint Oo Economic Corporation, President of Union Solidarity and Development Association K23a Chairman, Lt-Gen Tin Aung Myint Oo, Myanmar Economic Corporation 3 Dr. Sai Mao Kham Vice President Republic of the Union of @ Maung Ohn Myanmar 4 Major General Hla Minister Ministry of Defense B10a Major General Hla Chief of Bureau of Special Operation (3) Min Min 5 Lieutenant General Minister Ministry of Home Affairs A10a Maj-Gen Ko Ko Chief of Bureau of Special Operations 3 (Pegu, Ko Ko Irrawaddy, Arakan). 6 Major General Minister Ministry of Border Affairs and E28a Maj-Gen Thein Htay Deputy Minister for Defence Thein Htay Ministry of Myanmar Industrial Development 7 U Wunna Maung Minister Ministry of Foreign Affairs Lwin 8 U Kyaw Hsan Minister Ministry of Information and D17a Brig-Gen Kyaw Hsan Ministry of Information Ministry of Culture 9 U Myint Hlaing Minister Ministry of Agriculture and 115a Lt-Gen Myint Hlaing Ministry of Defence and USDA Member Irrigation 10 U Win Tun Minister Ministry -

Myanmar Maneuvers How to Break Political-Criminal Alliances in Contexts of Transition

United Nations University Centre for Policy Research Crime-Conflict Nexus Series: No 9 April 2017 Myanmar Maneuvers How to Break Political-Criminal Alliances in Contexts of Transition Dr. Vanda Felbab-Brown Senior Fellow, The Brookings Institution This material has been funded by UK aid from the UK government; however the views expressed do not necessarily reflect the UK government’s official policies. © 2017 United Nations University. All Rights Reserved. ISBN 978-92-808-9040-2 Myanmar Maneuvers How to Break Political-Criminal Alliances in Contexts of Transition 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Myanmar case study analyzes the complex interactions between illegal economies -conflict and peace. Particular em- phasis is placed on understanding the effects of illegal economies on Myanmar’s political transitions since the early 1990s, including the current period, up through the first year of the administration of Aung San Suu Kyi. Described is the evolu- tion of illegal economies in drugs, logging, wildlife trafficking, and gems and minerals as well as land grabbing and crony capitalism, showing how they shaped and were shaped by various political transitions. Also examined was the impact of geopolitics and the regional environment, particularly the role of China, both in shaping domestic political developments in Myanmar and dynamics within illicit economies. For decades, Burma has been one of the world’s epicenters of opiate and methamphetamine production. Cultivation of poppy and production of opium have coincided with five decades of complex and fragmented civil war and counterinsur- gency policies. An early 1990s laissez-faire policy of allowing the insurgencies in designated semi-autonomous regions to trade any products – including drugs, timber, jade, and wildlife -- enabled conflict to subside. -

Burma's Union Parliament Selects New President

CRS INSIGHT Burma's Union Parliament Selects New President March 18, 2016 (IN10464) | Related Policy Issue Southeast Asia, Australasia, and the Pacific Islands Related Author Michael F. Martin | Michael F. Martin, Specialist in Asian Affairs ([email protected], 7-2199) On March 15, 2016, Burma's Union Parliament selected Htin Kyaw, childhood friend and close advisor to Aung San Suu Kyi, to serve as the nation's first President since 1962 who has not served in the military. His selection as President-Elect completes another step in the nation's five-month-long transition from a largely military-controlled government to one led by the National League for Democracy (NLD). In addition, it also marks at least a temporary end to Aung San Suu Kyi's efforts to become Burma's President and may reveal signs of growing tensions between the NLD and the Burmese military. Htin Kyaw received the support of 360 of the 652 Members of Parliament (MPs), defeating retired Lt. General Myint Swe (who received 213 votes, of which 166 were from military MPs) and Henry Na Thio (who received 79 votes). The 69-year-old President-Elect is expected to be sworn into office on March 30, 2016. Myint Swe and Henry Van Thio will serve as 1st and 2nd Vice President, respectively. On November 8, 2015, Aung San Suu Kyi's National League for Democracy (NLD) won a landslide victory in nationwide parliamentary elections (see CRS Insight IN10397, Burma's Parliamentary Elections, by Michael F. Martin) that gave the party a majority of the seats in both chambers of Burma's Union Parliament. -

Myanmar Media: Legacy and Challenges

MYANMAR MEDIA: LEGACY AND CHALLENGES MARIA OCHWAT* Abstract: For nearly fifty years Myanmar was ruled by a military junta. It did not tolerate any criticism, and severely punished anyone who dared to oppose them. At the same time, it cut the country off from the rest of the world, preventing it from being informed about Burma’s internal situation. The announcement of the changes came when Thein Sein’s first civilian government was formed in 2011. Almost 10 years have passed since then and Myanmar, according to the Press Freedom Index, is considered to be one of the countries where freedom of speech and freedom of the media are commonly violated and journalists are often persecuted and punished. Freedom of expression is one of the pillars of a democratic society, the basis for its development and a condition for the self-fulfillment of the individual. One of the most important ways of exercising freedom of speech is through free and independent media. The issue of respect for freedom of expression and freedom of the media must be seen in a broader context. It should be noted that there is a close link between respect for human rights and peacekeeping. Although freedom of expression, and thus freedom of the media, is one of those freedoms which may be restricted in specific situations, it cannot be done arbitrarily. Under public international law the exercise of these freedoms, since it carries with it duties and responsibilities, may be subject to such formalities, conditions, restrictions or penalties as are prescribed by law and are necessary in a democratic society, in the interests of national security, territorial integrity or public safety, for the prevention of disorder or crime, for the protection of health or morals, for the protection of the reputation or rights of others, for preventing the disclosure of information received in confidence, or for maintaining the authority and impartiality of the judiciary. -

Remarks Following a Meeting with President Thein Sein of Burma in Ran- Goon, Burma November 19, 2012

Administration of Barack Obama, 2012 / Nov. 19 We appreciate your support in bringing de- people. We’ve seen it in the resilience that has mocracy in Thailand back on track. I hope you pushed this Nation forward, most recently, in continue to do so as Thailand’s democracy still the face of devastating floods. faces many challenges ahead. And most of all, I think we all feel here to- In terms of economic relations, as the Presi- night the unique friendship between our peo- dent and I have discussed today, we will contin- ples. His Majesty once said that since he was ue to build on a strong foundations in expanding born in America, the United States is “half my our trade and investment to promote growth motherland.” And we are just as proud of all the and create jobs. The world is changing fast, and Thai Americans who enrich our country. In only through trust, partnership, can we ensure fact, I was mentioning to His Majesty that my peace and prosperity for both nations. friend, Ladda Tammy Duckworth, just became Excellencies, ladies and gentlemen, for me the first Thai American woman ever to be elect- there is no better way to launch a celebration ed to our Congress, and she’s from my home of our 180th anniversary of relations in 2013 State of Illinois, so I’m especially proud of her. than with this Presidential visit today. May I in- Everything that I’ve felt—your dignity, vite all of you to join me in toast: To the good your resilience, your friendship, your health and success of President Barack Obama warmth—that is the foundation of our alli- and to the long-lasting friendship between the ance. -

ASG Analysis: Myanmar Military Seizes Power February 2, 2021

ASG Analysis: Myanmar Military Seizes Power February 2, 2021 Key Takeaways • The Tatmadaw (Myanmar military) arrested the leaders of the National League for Democracy (NLD) in coordinated early morning raids February 1, bringing to conclusion a month of escalating tensions and overthrowing Myanmar’s government 10 years after the country returned to democracy. • The coup thus far has been bloodless, but there have been reports of military supporters harassing journalists and NLD sympathizers, and many analysts fear violence could erupt in major cities such as Yangon and Mandalay, where resentment of the military runs deep. The Tatmadaw’s justification for the coup was alleged voter fraud in the 2020 general election. • While the Tatmadaw has announced it intends to hold “free and fair elections” and hand over power to the winner, it will likely attempt to reform electoral rules further in order to have more control over the outcome. • ASG expects the Biden administration to place sanctions on Myanmar’s military government, likely through the Global Magnitsky Act rather than any new structure. Military holding companies such as Myanmar Economic Corporation (MEC) and Myanma Economic Holdings Limited (MEHL) are likely targets. Those two entities are so significant within the country’s economy that renewed sanctions on them would make U.S. investment in the country extremely difficult. Democratically elected government overthrown in first coup since 1988 The Tatmadaw (Myanmar military) arrested the leaders of the National League for Democracy (NLD) in coordinated early morning raids February 1, bringing to conclusion a month of escalating tensions and overthrowing Myanmar’s government 10 years after the country returned to democracy. -

Myanmar's Foreign Policy Under President U Thein Sein

ISSN 0219-3213 2016 no. 4 Trends in Southeast Asia MYANMAR’S FOREIGN POLICY UNDER PRESIDENT U THEIN SEIN: NON-ALIGNED AND DIVERSIFIED JÜRGEN HAACKE TRS4/16s ISBN 978-981-4762-25-0 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace Singapore 119614 http://bookshop.iseas.edu.sg 9 7 8 9 8 1 4 7 6 2 2 5 0 Trends in Southeast Asia 16-0860 01 Trends_2016-04.indd 1 19/4/16 3:43 pm The ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute (formerly Institute of Southeast Asian Studies) was established in 1968. It is an autonomous regional research centre for scholars and specialists concerned with modern Southeast Asia. The Institute’s research is structured under Regional Economic Studies (RES), Regional Social and Cultural Studies (RSCS) and Regional Strategic and Political Studies (RSPS), and through country- based programmes. It also houses the ASEAN Studies Centre (ASC), Singapore’s APEC Study Centre, as well as the Nalanda-Sriwijaya Centre (NSC) and its Archaeology Unit. 16-0860 01 Trends_2016-04.indd 2 19/4/16 3:43 pm 2016 no. 4 Trends in Southeast Asia MYANMAR’S FOREIGN POLICY UNDER PRESIDENT U THEIN SEIN: NON-ALIGNED AND DIVERSIFIED JÜRGEN HAACKE 16-0860 01 Trends_2016-04.indd 3 19/4/16 3:43 pm Published by: ISEAS Publishing 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace Singapore 119614 [email protected] http://bookshop.iseas.edu.sg © 2016 ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, Singapore All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission. -

Myanmar's ASEAN Chairmanship

MYANMAR’S ASEAN CHAIRMANSHIP GREAT POWERS AND THE CHANGING MYANMAR ISSUE BRIEF NO. 4 SEPTEMBER 2014 Myanmar’s ASEAN Chairmanship By Yun Sun This issue brief discusses Myanmar’s relationship with ASEAN, its agenda for chairmanship in 2014 and an early assessment of its performance. KEY FINDINGS: 1 Myanmar assumed the chair- 2 2014 is a critical year lead- maintain balance between safe- manship of the Association ing to the establishment of guarding ASEAN solidarity and of Southeast Asian Nations ASEAN Community in 2015. managing its bilateral relation- (ASEAN) in 2014 for the first Under the theme “Moving ship with China. time since ASEAN was created Forward in Unity to a Peaceful 4 To date, Myanmar has suc- in 1967. The “normalization” and Prosperous Community,” cessfully carried out its role of Myanmar with the region- Myanmar sees it as a priori- as chair of ASEAN, despite al organization after decades ty to shepherd the process. its volatile domestic situation of turbulent relations has 3 The maritime territorial dis- and logistical challenges. symbolic and practical sig- putes and rising tensions in the nificance for the nation, the South China Sea present a major region and the organization. dilemma for Myanmar to This is the fourth of a series of four issue briefs on the changes and challenges that Myanmar faces in its domestic and foreign policies since the beginning of the nation’s de- mocratization in 2011. These briefs explore how external factors and forces influence and shape various aspects of Myanmar’s internal development, including economic growth, ethnic conflict and national reconciliation, as well as the foreign policy strategies of the Thein Sein government. -

The Rohingyas of Myanmar

Issue Brief # 222 Innovative Research | Independent Analysis | Informed Opinion Rudderless & Drowning in Tears The Rohingyas of Myanmar Roomana Hukil & Nayantara Shaunik Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies Within Myanmar there appears to be a And what has been the response of the decisive state policy designed in the international community so far? Will the interest of the government, military junta, Rohingyas continue to remain as, what Buddhist Rakhine, nationalist parties and has been termed by the UN - one of the other ethnical factions. With the 1978 most persecuted minorities in the world? ‘ethnic cleansing’ propaganda targeted against the Rohingya community, I Myanmar, has witnessed one of the most The Boat People: Rudderless & devastated large-scale sectarian strife’s in Drowning in Tears history. Albeit, political pressure, Myanmar, till today, maintains its ideological fancy in The Rohingyas identify themselves as the its inhumane treatment exhibited towards native settlers of Myanmar backed to the the Rohingya. This national venture whilst 7th century and disregard all literature supported by other Buddhist nations that propagates them as illegal migrants. predominantly of Burman and Rakhine For them, they are the native settlers who majority groups has left the Rohingya are being persecuted due to their varying community a dismantled lot. However, it linguistic and cultural traits. was only until 2009, when a worldwide coverage of the plight of the Rohingya The Rohingya highlight their grievances by vehemently spurred the international advocating the atrocities directed community in providing immediate towards them. They re-emphasize that reprieve to the issue. Within the larger they have been clustered into forced framework of social dynamics in labour with their lands confiscated by the Myanmar, this brief focuses on the ethnic Myanmarese Army. -

Burma's Political Prisoners and U.S. Policy

Burma’s Political Prisoners and U.S. Policy Updated January 4, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R44804 Burma’s Political Prisoners and U.S. Policy Summary Despite a campaign pledge in 2015 that they “would not arrest anyone as political prisoners,” Aung San Suu Kyi and the National League for Democracy (NLD) have failed to fulfil this promise since they took control of Burma’s Union Parliament and the government’s executive branch in April 2016. While presidential pardons have been granted for some political prisoners, people continue to be arrested, detained, tried, and imprisoned for political reasons. According to the Assistance Association of Political Prisoners (Burma), or AAPP(B), a Thailand-based, nonprofit human rights organization formed in 2000 by former Burmese political prisoners, there were 590 “individuals oppressed due to political activity”—including 35 sentenced to prison—as of the end of November 2020. During its five years in power, the NLD government has provided pardons for Burma’s political prisoners on seven occasions. The latest was on April 17, 2020, when President Win Myint pardoned nearly 25,000 prisoners, of which 10 were considered political prisoners by AAPP(B). Aung San Suu Kyi and her government, as well as the Burmese military, however, also have demonstrated a willingness to use Burma’s laws to suppress the opinions of their political opponents and restrict press freedoms. In April 2020, several reporters were charged under Article 50 (a) and Article 52 (a) of the 2014 Counter-Terrorism Law for publishing interviews with representatives of the Arakan Army, an ethnic armed organization that the NLD government has officially declared a terrorist group.