Tribute to Our S/Heroes Volume Ii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

November 13, 2010 Prices Realized

SCP Auctions Prices Realized - November 13, 2010 Internet Auction www.scpauctions.com | +1 800 350.2273 Lot # Lot Title 1 C.1910 REACH TIN LITHO BASEBALL ADVERTISING DISPLAY SIGN $7,788 2 C.1910-20 ORIGINAL ARTWORK FOR FATIMA CIGARETTES ROUND ADVERTISING SIGN $317 3 1912 WORLD CHAMPION BOSTON RED SOX PHOTOGRAPHIC DISPLAY PIECE $1,050 4 1914 "TUXEDO TOBACCO" ADVERTISING POSTER FEATURING IMAGES OF MATHEWSON, LAJOIE, TINKER AND MCGRAW $288 5 1928 "CHAMPIONS OF AL SMITH" CAMPAIGN POSTER FEATURING BABE RUTH $2,339 6 SET OF (5) LUCKY STRIKE TROLLEY CARD ADVERTISING SIGNS INCLUDING LAZZERI, GROVE, HEILMANN AND THE WANER BROTHERS $5,800 7 EXTREMELY RARE 1928 HARRY HEILMANN LUCKY STRIKE CIGARETTES LARGE ADVERTISING BANNER $18,368 8 1930'S DIZZY DEAN ADVERTISING POSTER FOR "SATURDAY'S DAILY NEWS" $240 9 1930'S DUCKY MEDWICK "GRANGER PIPE TOBACCO" ADVERTISING SIGN $178 10 1930S D&M "OLD RELIABLE" BASEBALL GLOVE ADVERTISEMENTS (3) INCLUDING COLLINS, CRITZ AND FONSECA $1,090 11 1930'S REACH BASEBALL EQUIPMENT DIE-CUT ADVERTISING DISPLAY $425 12 BILL TERRY COUNTERTOP AD DISPLAY FOR TWENTY GRAND CIGARETTES SIGNED "TO BARRY" - EX-HALPER $290 13 1933 GOUDEY SPORT KINGS GUM AND BIG LEAGUE GUM PROMOTIONAL STORE DISPLAY $1,199 14 1933 GOUDEY WINDOW ADVERTISING SIGN WITH BABE RUTH $3,510 15 COMPREHENSIVE 1933 TATTOO ORBIT DISPLAY INCLUDING ORIGINAL ADVERTISING, PIN, WRAPPER AND MORE $1,320 16 C.1934 DIZZY AND DAFFY DEAN BEECH-NUT ADVERTISING POSTER $2,836 17 DIZZY DEAN 1930'S "GRAPE NUTS" DIE-CUT ADVERTISING DISPLAY $1,024 18 PAIR OF 1934 BABE RUTH QUAKER -

PDF of August 17 Results

HUGGINS AND SCOTT'S August 3, 2017 AUCTION PRICES REALIZED LOT# TITLE BIDS 1 Landmark 1888 New York Giants Joseph Hall IMPERIAL Cabinet Photo - The Absolute Finest of Three Known Examples6 $ [reserve - not met] 2 Newly Discovered 1887 N693 Kalamazoo Bats Pittsburg B.B.C. Team Card PSA VG-EX 4 - Highest PSA Graded &20 One$ 26,400.00of Only Four Known Examples! 3 Extremely Rare Babe Ruth 1939-1943 Signed Sepia Hall of Fame Plaque Postcard - 1 of Only 4 Known! [reserve met]7 $ 60,000.00 4 1951 Bowman Baseball #253 Mickey Mantle Rookie Signed Card – PSA/DNA Authentic Auto 9 57 $ 22,200.00 5 1952 Topps Baseball #311 Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 40 $ 12,300.00 6 1952 Star-Cal Decals Type I Mickey Mantle #70-G - PSA Authentic 33 $ 11,640.00 7 1952 Tip Top Bread Mickey Mantle - PSA 1 28 $ 8,400.00 8 1953-54 Briggs Meats Mickey Mantle - PSA Authentic 24 $ 12,300.00 9 1953 Stahl-Meyer Franks Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 (MK) 29 $ 3,480.00 10 1954 Stahl-Meyer Franks Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 58 $ 9,120.00 11 1955 Stahl-Meyer Franks Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 20 $ 3,600.00 12 1952 Bowman Baseball #101 Mickey Mantle - PSA FR 1.5 6 $ 480.00 13 1954 Dan Dee Mickey Mantle - PSA FR 1.5 15 $ 690.00 14 1954 NY Journal-American Mickey Mantle - PSA EX-MT+ 6.5 19 $ 930.00 15 1958 Yoo-Hoo Mickey Mantle Matchbook - PSA 4 18 $ 840.00 16 1956 Topps Baseball #135 Mickey Mantle (White Back) PSA VG 3 11 $ 360.00 17 1957 Topps #95 Mickey Mantle - PSA 5 6 $ 420.00 18 1958 Topps Baseball #150 Mickey Mantle PSA NM 7 19 $ 1,140.00 19 1968 Topps Baseball #280 Mickey Mantle PSA EX-MT -

(Emtttprttrut Satltj (Ftampitb VOLLXV11N07 Serving Storrs Since 1896 SEPT 25,1969

(EmtttPrttrut Satltj (ftampitB VOLLXV11N07 Serving Storrs Since 1896 SEPT 25,1969 "t^*1 Chicago 8 Bout 'Conspiracy' In Court Story On Page 3 TIIP Oii-ago Fight were brought to trial yesterday on charges of conspiring to set off bloody confrontations between police and anti-war demonstrators at the 1968 Chicago Democratic National Convention. Selection of jurors was scheduled to begin vesterday morning. The eight, who call themselves "The Conspiracy," said they will rally their supporters to demonstrate against the trial. Explaining the proposed construction of the new Graduate Center going up In the West Campus area Is Richard E. Swibold, a member of the architectural firm handling the project. At the meeting yester- day in the Museum of Art, it was announced that one of the Center structures a psychology building, should be completed by mid-winter. Also planned for the Center are dormitories, a Graduate Facilities building and a Graduate Club. Tear Gas Bomb Forces Fraternity Evacuation No Injuries to AEPi Residents Reported Story on Page Three A tear gas bomb that went off in the basement of Alpha Epsilon Pi fraternity house Tuesday night forced about 63 residents of the house to evacuate. No injuries or damage was reported. After gas-clear- ing efforts by UConn Security, occupants were allowed back into the building around noon yesterday. $30 Million, 2000-Living Unit Complex Planned Ashford-Willington Line Site of Project Story on Page Four Two thousand living units, a shopping center and an 18-hole golf course will be Included in a planned residential and commercial complex four miles from campus. -

Fight Against Negro Players HELENA, Ark

•' : . : -v', y; : . rs I Cotton States League To Push fight Against Negro Players HELENA, Ark. (ANP) Despite the ruling by President MIAMITIMES. MIAMI. FLORIDA George Trautman of the National Association of Professional (min- SATURDAY, JUNE 20, 1953 PAGE FIVE or) Baseball leagues that no min- or league has any rule against Ne- groes playing, the Cotton States Class C loop declared last week that it will continue its fight to keep Negroes of the loop. Wins British out Turpin President A1 Haraway of the Cotton States league announced that the circuit will appeal Trautman’s ruling ordering the Version Os World Title playing of a game scheduled for May 20, but forfeited by Hot LONDON (ANP) Randy Springs to Jackson, Miss, because Turpin of England defeated MANAGER TO Hot Springs listed the ‘name of Charley Humez of France to win Jim Tugerson, a Negro pitcher, the British version of the middle- CHALLENGE on its roster. weight championship of the world 'Haraway declared: in a 15 round bout in which the BOXING COMMISH “Trautman’s decision will be winner showed little aggressive- RIGHT TO appealed to the executive com- ness. mittee of the National Associa- • A full house of 54,000 fans who SUSPEND HIM tion of Professional Baseball paid more than $255,000 cheered leagues.” the loser as he tried hard to rally TOLEDO, O. (ANP) The He objected to Trautman's himselfbehind a losing cause. Tur- right of the Toledo Boxing Com- voiding of an agreement be- pin was too good a boxer and mission to suspend a fight man- tween the Hot Springs Bathers puncher for the Frenchman, ager may be subjected to a court and the other clubs in the league however. -

YAF Stops Action Laurence Lattman

Inj unc tion Lifted; The World YAF Stops Action , Norm U. S. Forces Discover Large Arms Cache By LINDA OtSHESKY the restraining order were Martin Zehur Schwartz. Tom Richdale. Russ Farb. Laurey SAIGON — A big enemy arms cache was found yes- Collegian Staff Writer terday by U.S. forces 52 miles north of Saigon, spokesmen Petkov. Stephen Eis and Jeff Berger. said , in another setback for • the Communist command, The court injunction obtained by members Laura Wcrtheimer. Jack Swisher. K. which has lost 38,000 weapons since its offensive was of Young Americans For Freedom against Charles Betzko and YAF obtained the order launched Feb. 23. seven named students and SO John and Jane from Judge R. Paul Campbell. In addition to the men killed and weapons captured, Does was lifted yesterday at 5 p.m. The demonstration that caused the in- the enemy has lost 2,500 rockets and 110,000 mortar rounds A sit-in demonstration led by members of junction to be served began at 12:30 p.m. w ith to allied forces in the Vs-month-old offensive, the U.S. Students for a Democratic Society against the singing of protest and anti-war songs. Command said. military recruiters sparked YAF to seek the Demonstrators were permitted to sit in Unconfirmed field reports said the cache discovered restraining order. YAF claimed t h e front of the recruiting table. A path leading to yesterday included 91 machine guns .and a number of demonstrators were blocking the aisles in the the table wa.s kept open by the demonstrators mortars, ' Hetzel Union Building. -

Official Game Information

Official Game Information Yankee Stadium • One East 161st Street • Bronx, NY 10451 Media Relations Phone: (718) 579-4460 • [email protected] • Twitter: @yankeespr YANKEES BY THE NUMBERS NOTE 2012 (Postseason) 2012 AMERICAN LEAGUE CHAMPIONSHIP SERIES – GAME 1 Home Record: . 51-30 (2-1) NEW YORK YANKEES (3-2/95-67) vs. DETROIT TIGERS (3-2/88-74) Road Record: . 44-37 (1-1) Day Record: . .. 32-20 (---) LHP ANDY PETTITTE (0-1, 3.86) VS. RHP DOUG FISTER (0-0, 2.57) Night Record: . 63-47 (3-2) Saturday, OctOber 13 • 8:07 p.m. et • tbS • yankee Stadium vs . AL East . 41-31 (3-2) vs . AL Central . 21-16 (---) vs . AL West . 20-15 (---) AT A GLANCE: The Yankees will play Game 1 of the 2012 American League Championship Series vs . the Detroit Tigers tonight at Yankee Stadium…marks the Yankees’ 15th ALCS YANKEES IN THE ALCS vs . National League . 13-5 (---) (Home Games in Bold) vs . RH starters . 58-43 (3-0) all-time, going 11-3 in the series, including a 7-2 mark in their last nine since 1996 – which vs . LH starters . 37-24 (0-2) have been a “best of seven” format…is their third ALCS in five years under Joe Girardi (also YEAR OPP W L Detail Yankees Score First: . 59-27 (2-1) 2009 and ‘10)…are 34-14 in 48 “best-of-seven” series all time . 1976** . KC . 3 . 2 . WLWLW Opp . Score First: . 36-40 (1-1) This series is a rematch of the 2011 ALDS, which the Tigers won in five games . -

Criminal Law & Practice Section MCLE Program Webinar November

Criminal Law & Practice Section MCLE Program Webinar November 9, 2020 12:00 AM – Noon Welcome/Introductions Charles Rohde, Section Chair Noon – 1:00 PM Program Stalking Laws in Illinois including Criminal and Civil penalties with a telling of the true story behind “The Natural”. Jae K. Kwon - Anderson Attorneys & Advisors; and Dean C. Paul Rogers - SMU Dedman School of Law. Speakers’ Bios are attached A discussion about Stalking in Illinois - the criminal offense and civil ramifications including Stalking orders of protection. The CLE will also feature a re-telling of the 1949 Chicago shooting of baseball player Eddie Waitkus, the subsequent legal proceedings, his baseball career and the true-life inspiration for the movie "The Natural". Link to Evaluation The evaluation must be completed in order to receive CLE credit. https://www.surveymonkey.com/r/Criminal11092020 Next Meeting: 12/1/2020 Special Newsletter Motion to Vacate & Expunge Eligible Cannabis Convictions Form Suite Approved for Public Comment –The Administrative Office of Illinois Courts has announced that “Motion to Vacate & Expunge Eligible Cannabis Convictions” draft forms are available for public comment. If you follow the link below, it will take you to the page where you can view the draft forms. Once on this page, you can access the draft forms listed in the box titled “DRAFT FORMS FOR COMMENT”. The public comment period will be open for 45 days. After that time, the commission will review any feedback or suggestions received and make any revisions it deems necessary. http://www.illinoiscourts.gov/Forms/forms.asp Addison Field Court Relocating to Glendale Heights - The 1st Amendment to Administrative Order 20-37 provides that, effective December 7, 2020, the Addison Traffic Court currently being held in the annex rooms of the main courthouse will move into the Glendale Heights facility located at 300 Civic Centre Plaza. -

Full Page Version

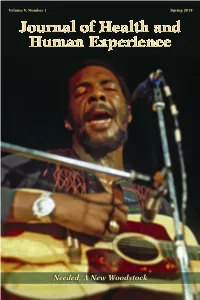

Volume V, Number 1 Spring 2019 Journal of Health and Human Experience Needed, A New Woodstock The photograph on the front cover is by Heinrich Klaffs. Journal of Health and Human Experience The Journal of Health and Human Experience is published by The Semper Vi Foundation. Journal of Health and Human Experience Volume V, No. 1 PrefaceJournal of Health and Human Experience General Information The Journal of Health and Human Experience is published by The Semper Vi Foundation, a 501(c)(3) public charity. The Journal is designed to benefit international academic and professional inquiry regarding total holistic health, the arts and sciences, human development, human rights, and social justice. The Journal promotes unprecedented interdisciplinary scholarship and academic excellence through explorations of classical areas of interest and emerging horizons of multicultural and global significance. ISSN 2377-1577 (online). Correspondence Manuscripts are to be submitted to the Journal Leadership. Submission of a manuscript is considered to be a representation that it is not copyrighted, previously published, or concurrently under consideration for publishing by any other entity in print or electronic form. Contact the Journal Leadership for specific information for authors, templates, and new material. The preferred communication route is through email at [email protected]. Subscriptions, Availability and Resourcing The Journal is supported completely by free will, charitable donations. There are no subscription fees. Online copies of all editions of the Journal are freely available for download at: http://jhhe.sempervifoundation.org. To make a donation, contact: [email protected]. You will be contacted in reply as soon as possible with the necessary information. -

Last Tango in Paris (1972) Dramas Bernardo Bertolucci

S.No. Film Name Genre Director 1 Last Tango in Paris (1972) Dramas Bernardo Bertolucci . 2 The Dreamers (2003) Bernardo Bertolucci . 3 Stealing Beauty (1996) H1.M Bernardo Bertolucci . 4 The Sheltering Sky (1990) I1.M Bernardo Bertolucci . 5 Nine 1/2 Weeks (1986) Adrian Lyne . 6 Lolita (1997) Stanley Kubrick . 7 Eyes Wide Shut – 1999 H1.M Stanley Kubrick . 8 A Clockwork Orange [1971] Stanley Kubrick . 9 Poison Ivy (1992) Katt Shea Ruben, Andy Ruben . 1 Irréversible (2002) Gaspar Noe 0 . 1 Emmanuelle (1974) Just Jaeckin 1 . 1 Latitude Zero (2000) Toni Venturi 2 . 1 Killing Me Softly (2002) Chen Kaige 3 . 1 The Hurt Locker (2008) Kathryn Bigelow 4 . 1 Double Jeopardy (1999) H1.M Bruce Beresford 5 . 1 Blame It on Rio (1984) H1.M Stanley Donen 6 . 1 It's Complicated (2009) Nancy Meyers 7 . 1 Anna Karenina (1997) Bernard Rose Page 1 of 303 1 Fanny Hill: Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure (1964) Russ Meyer 9 . 2 Vixen! By Russ Meyer (1975) By Russ Meyer 0 . 2 Deep Throat (1972) Fenton Bailey, Randy Barbato 1 . 2 A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE (1951) Elia Kazan 2 . 2 Pandora Peaks (2001) Russ Meyer 3 . 2 The Lover (L'amant) 1992 Jean-Jacques Annaud 4 . 2 Damage (1992) Louis Malle 5 . 2 Close My Eyes (1991) Stephen Poliakoff 6 . 2 Casablanca 1942 H1.M Michael Curtiz 7 . 2 Duel in the Sun (film) (1946) I1.M King Vidor 8 . 2 The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957) H1.M David Lean 9 . 3 Caligula (1979) Tinto Brass 0 . -

THEDAILY VWPTQTWV FINAL Clearing, Colder Tonight

Bargain Hunters Regarded Criminals' Aides STORY PAGE 21 Rainy and Cold Rainy, windy and cold today. THEDAILY VWPTQTWV FINAL Clearing, colder tonight. Fair and cold tomorrow. EDITION (Bee Details, Pan 2) Monmouth County's Home Newspaper for 92 Years VOL. 93, NO. 124 RED BANK, N. J., MONDAY, DECEMBER 22, 1969 36 PAGES / 10 CENTS lllilllIililillIllllllllililliIIlllI||||||!lllBi|||||i|i;|]|i|ii!|[Bi, illtB!llililIlllliilIIII!lllllli» State Crime Probe Continues As Juries Take Yule Recess NEWARK (AP) - The out only on Christmas Day. published reports about including city officials, con- son County, the location of three grand juries investigat- U.S. Atty. Frederick B. La- where the investigations will tractors and reputed Mafia one of the oldest political ma- ing corruption and under- cey says the gran dpuries will strike next. chief Anthony "Tony Boy" chines in the nation, has been world activity in New Jersey meet again the week after Mayor Indicted Boiardo on charges of extor- marked as the second target will not meet this Christmas Christmas, however. Last week saw the indict- tion and tax evasion in con- of the federal investigation. week but investigators will The state, though, is rife ment of Newark Mayor Hugh nection with city contracts. Meanwhile Lacey, who is continue their work with time with rumors, speculation and J. Addonizio and 14 others, Those indictments came heading the investigations, re- only a day after 55 persons, plies "no comment" to all including Mafia boss Simone questions on where the probes "Sam the Plumber" DeCav- are going. He will only say, alcante were charged by an- "the investigations are con- other federal grand jury sit- tinuing." ting in Newark in connection He also will say only "No with a $20 million a year comment," when asked if gambling operation. -

Finding Aid for the Henry Clay Frick Papers, Series II: Correspondence, 1882-1929

Finding aid for the Henry Clay Frick Papers, Series II: Correspondence, 1882-1929, TABLE OF CONTENTS undated Part of the Frick Family Papers, on deposit from the Helen Clay Frick Foundation Summary Information SUMMARY INFORMATION Biographical Note Scope and Content Repository The Frick Collection/Frick Art Reference Library Archives Arrangement 10 East 71st Street Administrative New York, NY, 10021 Information [email protected] © 2010 The Frick Collection. All rights reserved. Controlled Access Headings Creator Frick, Henry Clay, 1849-1919. Collection Inventory Title Henry Clay Frick Papers, Series II: Correspondence ID HCFF.1.2 Date 1882-1929, undated Extent 39.4 Linear feet (95 boxes) Abstract Henry Clay Frick (1849-1919), a Pittsburgh industrialist who made his fortune in coke and steel, was also a prominent art collector. This series consists largely of Frick's incoming correspondence, with some outgoing letters, on matters relating to business and investments, art collecting, political activities, real estate, philanthropy, and family matters. Preferred Citation Henry Clay Frick Papers, Series II: Correspondence. The Frick Collection/Frick Art Reference Library Archives. Return to Top » BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Henry Clay Frick was born 19 December 1849, in West Overton, Pa. One of six children, his parents were John W. Frick, a farmer, and Elizabeth Overholt Frick, the daughter of a whiskey distiller and flour merchant. Frick ended his formal education in 1866 at the age of seventeen, and began work as a clerk at an uncle's store in Mt. Pleasant, Pa. In 1871, Frick borrowed money to purchase a share in a coking concern that would eventually become the H.C. -

Hofstra University Film Library Holdings

Hofstra University Film Library Holdings TITLE PUBLICATION INFORMATION NUMBER DATE LANG 1-800-INDIA Mitra Films and Thirteen/WNET New York producer, Anna Cater director, Safina Uberoi. VD-1181 c2006. eng 1 giant leap Palm Pictures. VD-825 2001 und 1 on 1 V-5489 c2002. eng 3 films by Louis Malle Nouvelles Editions de Films written and directed by Louis Malle. VD-1340 2006 fre produced by Argosy Pictures Corporation, a Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer picture [presented by] 3 godfathers John Ford and Merian C. Cooper produced by John Ford and Merian C. Cooper screenplay VD-1348 [2006] eng by Laurence Stallings and Frank S. Nugent directed by John Ford. Lions Gate Films, Inc. producer, Robert Altman writer, Robert Altman director, Robert 3 women VD-1333 [2004] eng Altman. Filmocom Productions with participation of the Russian Federation Ministry of Culture and financial support of the Hubert Balls Fund of the International Filmfestival Rotterdam 4 VD-1704 2006 rus produced by Yelena Yatsura concept and story by Vladimir Sorokin, Ilya Khrzhanovsky screenplay by Vladimir Sorokin directed by Ilya Khrzhanovsky. a film by Kartemquin Educational Films CPB producer/director, Maria Finitzo co- 5 girls V-5767 2001 eng producer/editor, David E. Simpson. / una produzione Cineriz ideato e dirètto da Federico Fellini prodotto da Angelo Rizzoli 8 1/2 soggètto, Federico Fellini, Ennio Flaiano scenegiatura, Federico Fellini, Tullio Pinelli, Ennio V-554 c1987. ita Flaiano, Brunello Rondi. / una produzione Cineriz ideato e dirètto da Federico Fellini prodotto da Angelo Rizzoli 8 1/2 soggètto, Federico Fellini, Ennio Flaiano scenegiatura, Federico Fellini, Tullio Pinelli, Ennio V-554 c1987.