Opil 38 of 2012 Has Also Been Published Together with Opil 37

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FY2018-19.Pdf

HEIDELBERGCEMENT INDIA LIMITED UNCLAIMED / UNPAID FINAL DIVIDEND FOR 2018-19 AS AT 31.03.2020 DIVIDEND PROPOSED DATE OF DIV_YEAR FOLIO / DPID_CLID NAME_1 ADDRESS SHARES WAR_NO MICR_NO DIVIDEND_DATE AMOUNT (RS) TRANSFER IEPF 2018-19 (FINAL) IN30096610090890 CAPITAL MERCHANTS PRIVATE LIMITED 2778/21 HAMILTON ROAD MORI GATE DELHI-110006 1000 3000.00 4 561 25-SEP-2019 24-OCT-2026 2018-19 (FINAL) D000052 SANYOKTA DEVI B/266-A GREATER KAILASHI NEW DELHI NEW DELHI-110014 540 1620.00 8 565 25-SEP-2019 24-OCT-2026 2018-19 (FINAL) A001878 ANIL KAPUR S-175 PANCHSHILA PARK NEW DELHI NEW DELHI-110017 700 2100.00 10 567 25-SEP-2019 24-OCT-2026 2018-19 (FINAL) S001064 SARLA GOYAL B 53 SOAMI NAGAR NEW DELHI NEW DELHI-110017 600 1800.00 12 569 25-SEP-2019 24-OCT-2026 2018-19 (FINAL) V001419 VIBHA KAPUR S-175 PANCHSHILA PARK NEW DELHI NEW DELHI-110017 700 2100.00 13 570 25-SEP-2019 24-OCT-2026 2018-19 (FINAL) C002513 S CHUGH 607 SHAKUNTALA APARTMENTS 59 NEHRU PLACE NEW DELHI NEW DELHI-110019 600 1800.00 16 573 25-SEP-2019 24-OCT-2026 2018-19 (FINAL) C001490 ARJUN CHOUDHRY (MINOR) B 73 LAJPAT NAGAR 2 NEW DELHI NEW DELHI-110024 550 1650.00 18 575 25-SEP-2019 24-OCT-2026 2018-19 (FINAL) S002835 SWARCH MAHAJAN 610-A POCKET A SARITA VIHAR NEW DELHI NEW DELHI-110044 757 2271.00 20 577 25-SEP-2019 24-OCT-2026 2018-19 (FINAL) IN30096610270678 VANITA JAIN B-227 (FIRST FLOOR) ASHOK VIHAR PHASE-I DELHI-110052 1000 3000.00 22 579 25-SEP-2019 24-OCT-2026 2018-19 (FINAL) B000030 DHARAM PAL BAJAJ C-582,NEW FRIENDS COLONY NEW DELHI NEW DELHI-110065 595 1785.00 26 583 25-SEP-2019 -

To Download Branch Wise Placement Data in Pdf Format

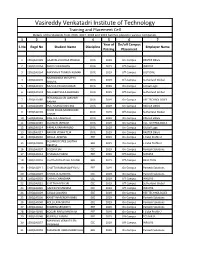

Vasireddy Venkatadri Institute of Technology Training and Placement Cell Details of the Students from 2016, 2017, 2018 and 2019 batches placed in various companies 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Year of On/off Campus S.No Regd No Student Name Discipline Employer Name Passing Placement 1 15BQ1A0129 GAJAVALLI DURGA PRASAD CIVIL 2019 On-Campus RASTER ENGG 2 15BQ1A0154 MADA VISWANATH CIVIL 2019 Off-Campus INFOSYS 3 15BQ1A0164 MANNAVA THARUN KUMAR CIVIL 2019 Off-Campus JUST DIAL MUDIGONDA SRI SATYA 4 15BQ1A0170 CIVIL 2019 Off-Campus Sutherland Global SRAVYA 5 15BQ1A0172 MUVVA PAVAN KUMAR CIVIL 2019 On-Campus Global Logic 6 15BQ1A0174 NALLABOTHULA BHARGAV CIVIL 2019 Off-Campus Sutherland Global PERUMALLA SRI LAKSHMI 7 15BQ1A0185 CIVIL 2019 On-Campus VEE TECHNOLOGIES RAMYA 8 15BQ1A0193 PULI MURALI KRISHNA CIVIL 2019 On-Campus RASTER ENGG SHAIK KHAJA MOINUDDIN 9 15BQ1A0199 CIVIL 2019 Off-Campus Sutherland Global CHISTY 10 15BQ1A01A6 SWETHA TADEPALLI CIVIL 2019 On-Campus RASTER ENGG 11 15BQ1A01B7 VELINENI JAHNAVI CIVIL 2019 On-Campus VEE TECHNOLOGIES 12 16BQ5A0114 PARALA VARAPRASAD CIVIL 2019 On-Campus Global Logic 13 16BQ5A0117 RAVURI VISWA TEJA CIVIL 2019 On-Campus RASTER ENGG 14 15BQ1A0202 AKILLA. APARNA EEE 2019 On-Campus L Cube Profile 2 ALLAMUDI SREE LALITHA 15 15BQ1A0203 EEE 2019 On-Campus L Cube Profile 2 DEEPTHI 16 15BQ1A0207 B SESHA SAI EEE 2019 On-Campus Pantech Solutions 17 15BQ1A0214 CHAGALA HARINI EEE 2019 Off-Campus SONATA 18 15BQ1A0216 CHATHARASUPALLI.PAVANI EEE 2019 Off-Campus RSAC TECH 19 15BQ1A0217 CHATTU RAMANJANEYULU EEE 2019 On-Campus Pantech -

Syndicate Bank - 1533 1 Gujjarlapudi Keerthi A.T.Agraharam 78 Kotagiri Vijaya Krishna Aravapalli 155 M Shiva Kumar Bellary 2 S

SOUVENIR - 2016 SYNDICATE BANK - 1533 1 GUJJARLAPUDI KEERTHI A.T.AGRAHARAM 78 KOTAGIRI VIJAYA KRISHNA ARAVAPALLI 155 M SHIVA KUMAR BELLARY 2 S. BALAKRISHNA NAIK A.VANDLAPALLI 79 B. AJAY KUMAR ARDHAVEEDU 156 P. HAREESH BELLARY 3 CHINNAM KIRAN KUMAR ABBUGUDEM 80 Y SRIKANTH ARDHAVEEDU 157 R GANAMALLI BELLARY 4 DUDEKULA RAHAMTHULLA ABDULLAPURAM 81 CHANDANA ALLADI ARMOOR 158 RAJU M BELLARY 5 K. NAGARAJU ABM PALEM 82 S. VENU GOPAL ARMOOR 159 S VIKRAM BELLARY 6 VEMULA SRINIVASA RAO ADAVULADEEVI 83 S VISHNU PRIYA ASHOKAPURAM 160 T. ASHOK KUMAR BELLARY 7 CH. ANURADHA ADDANKI 84 P. GOPI KRISHNA ASPARI 161 V MADHURI BELLARY 8 D.NAGENDRA ADDANKI 85 K MURTHUJA VALI ATAMAKUR 162 V. SURESH BABU BELLARY 9 K. VENKATESWARLU ADDANKI 86 K. RAMANJANEYULU ATCHAMPET 163 V.T. NAGESH BELLARY 10 RESHMA KIRAN SANDIPAGU ADDANKI 87 SANTOSH S HONAGOUD ATHANI 164 VIVEKANANDA V BELLARY 11 K. LAKSHMI SRAVYA ADDANKI 88 A.HARI NATH REDDY ATMAKUR 165 K S POORNIMA BELLARY 12 CHINTA SRINIVASA RAO ADDANKI 89 S. SIVA JYOTHI ATMAKUR 166 K RAMA BELLARY 13 CHAKARA SURESH ADDEPALLI 90 S.MRUTHUMJAYA REDDY ATMAKUR 167 V. SIVA KUMAR BELLARY 14 A. RANAVEER KUMAR ADILABAD 91 MARAPAKA KIRAN KUMAR ATMAKUR 168 RAJESH H.V BELLARY 15 CH. MAHESH BHAGWAN ADILABAD 92 SURASURA VENKATESH ATMAKUR 169 LEKIREDDY AMARNATH BELUGUPPA 16 SRIVATSA DEHAGAM ADILABAD 93 SK. SHARIF ATMAKUR 170 T. BASAVARAJA BENEKALLU 17 M LAXMAN ADILABAD 94 V. VENKATA REDDY ATTILI 171 ANANDKUMAR JAKKAM BESTAVARIPETA 18 A.M. VASUNDHARA BAI ADONI 95 M MAMESWARAN AVADI 172 V. SALEM JOJI BESTAVARIPETA 19 C. POMPAPATHI ADONI 96 P. -

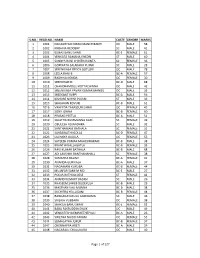

S.No. Regd.No. Name Caste Gender Marks 1 1001

S.NO. REGD.NO. NAME CASTE GENDER MARKS 1 1001 NAGASHYAM KIRAN MANCHIKANTI OC MALE 58 2 1002 KRISHNA REDDERY SC MALE 41 3 1003 ELMAS BANU SHAIK BC-E FEMALE 61 4 1004 VENKATA RAMANA KHEDRI ST MALE 60 5 1005 SANDYA RANI CHINTHAKUNTA SC FEMALE 36 6 1006 GOPINATH SALAKARU PUJARI SC MALE 28 7 1007 SREENIVASA REDDY GOTLURI OC MALE 78 8 1008 LEELA RANI B BC-A FEMALE 57 9 1009 RADHIKA KONDA OC FEMALE 30 10 1010 SREEDHAR M BC-D MALE 68 11 1011 CHANDRAMOULI KOTTACHINNA OC MALE 42 12 1012 SREENIVASA PAVAN KUMAR MANGU OC MALE 35 13 1013 SREEKANT SUPPI BC-A MALE 56 14 1014 KISHORE NAYAK PUJARI ST MALE 39 15 1015 SHAJAHAN KOVURI BC-B MALE 61 16 1016 VAHEEDA TABASSUM SHAIK OC FEMALE 45 17 1017 SONY JONNA BC-B FEMALE 60 18 1018 PRASAD PEETLA BC-A MALE 51 19 1019 SUJATHA BUMMANNA GARI SC FEMALE 49 20 1020 OBULESH ADIANDHRA SC MALE 32 21 1021 SANTHAMANI BATHALA SC FEMALE 31 22 1022 SARASWATHI GOLLA BC-D FEMALE 47 23 1023 LAVANYA GAJULA OC FEMALE 55 24 1024 SATEESH KUMAR MAHESWARAM BC-B MALE 38 25 1025 KRANTHI NALLAGATLA BC-B FEMALE 33 26 1026 RAVI KUMAR BATHALA BC-B MALE 68 27 1027 ADI LAKSHMI BANTHANAHALL SC FEMALE 38 28 1028 SAMATHA BALIMI BC-A FEMALE 41 29 1030 ANANDA GURIKALA BC-A MALE 37 30 1031 NAGAMANI KURUBA BC-B FEMALE 44 31 1032 MUJAFAR SAMI M MD BC-E MALE 27 32 1033 POOJA RATHOD DESE ST FEMALE 42 33 1034 ANAND KUMART BADIGI SC MALE 26 34 1035 KHASEEM SAHEB DUDEKULA BC-B MALE 29 35 1036 MASTHAN VALI MUNNA BC-B MALE 38 36 1037 SUCHITRA YELLUGANI BC-B FEMALE 44 37 1038 RANGANAYAKULU GUDIDAMA SC MALE 46 38 1039 SAILAJA VUBBARA OC FEMALE 38 39 1040 SHAKILA BANU SHAIK BC-E FEMALE 52 40 1041 BABA FAKRUDDIN SHAIK OC MALE 49 41 1042 VENKATESH DEMAKETHEPALLI BC-A MALE 26 42 1043 SWETHA NAIDU PAKAM OC FEMALE 55 43 1044 SUMALATHA JUKUR BC-B FEMALE 37 44 1047 CHENNAPPA ARETI BC-A MALE 29 45 1048 NAGARAJU CHALUKURU OC MALE 40 Page 1 of 127 S.NO. -

Advances in Unconventional Machining and Composites Proceedings of AIMTDR 2018

Lecture Notes on Multidisciplinary Industrial Engineering Series Editor J. Paulo Davim , Department of Mechanical Engineering, University of Aveiro, Aveiro, Portugal “Lecture Notes on Multidisciplinary Industrial Engineering” publishes special volumes of conferences, workshops and symposia in interdisciplinary topics of interest. Disciplines such as materials science, nanosciences, sustainability science, management sciences, computational sciences, mechanical engineering, industrial engineering, manufacturing, mechatronics, electrical engineering, environmental and civil engineering, chemical engineering, systems engineering and biomedical engineering are covered. Selected and peer-reviewed papers from events in these fields can be considered for publication in this series. More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/15734 M. S. Shunmugam • M. Kanthababu Editors Advances in Unconventional Machining and Composites Proceedings of AIMTDR 2018 123 Editors M. S. Shunmugam M. Kanthababu Manufacturing Engineering Section Department of Manufacturing Engineering Department of Mechanical Engineering College of Engineering, Guindy Indian Institute of Technology Madras Anna University Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India ISSN 2522-5022 ISSN 2522-5030 (electronic) Lecture Notes on Multidisciplinary Industrial Engineering ISBN 978-981-32-9470-7 ISBN 978-981-32-9471-4 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-32-9471-4 © Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd. 2020 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. -

Unpaid Dividend Data-2016-17 Final As at 31.3.2019

HEIDELBERGCEMENT INDIA LIMITED UNCLAIMED / UNPAID FINAL DIVIDEND FOR 2016-17 (FINAL) AS AT 31.3.2019 DIV_YEAR FOLIO / DPID_CLID NAME_1 ADDRESS SHARES DIVIDEND WAR_NO MICR_NO DIVIDEND_DATE PROPOSED DATE OF AMOUNT (RS) TRANSFER IEPF 2016-17 (FINAL) IN30096610090890 CAPITAL MERCHANTS PRIVATE LIMITED 2778/21 HAMILTON ROAD MORI GATE DELHI 110006 1000 2000.00 11 567 26-SEP-2017 28-OCT-2024 2016-17 (FINAL) A003410 MANOJ AGARWAL C/O K L AGARWALA & SONS 4124 NAYA BAZAR DELHI NEW DELHI 110006 1400 2800.00 12 568 26-SEP-2017 28-OCT-2024 2016-17 (FINAL) A003747 MANOJ KUMAR AGARWALA K L AGARWALA AND SONS 4124 NAYA BAZAR DELHI NEW DELHI 110006 1100 2200.00 13 569 26-SEP-2017 28-OCT-2024 2016-17 (FINAL) B000066 BHAGIRATHMAL MERCHANT C/O M/S RAMJI LAL RAMSAROOP HAUZ QAZI DELHI NEW DELHI 110006 865 1730.00 15 571 26-SEP-2017 28-OCT-2024 2016-17 (FINAL) S002835 SWARCH MAHAJAN 610-A POCKET A SARITA VIHAR NEW DELHI NEW DELHI 110044 757 1514.00 22 578 26-SEP-2017 28-OCT-2024 2016-17 (FINAL) IN30096610270678 VANITA JAIN B-227 (FIRST FLOOR) ASHOK VIHAR PHASE-I DELHI 110052 1000 2000.00 24 580 26-SEP-2017 28-OCT-2024 2016-17 (FINAL) K001842 ROSHAN LAL KOHLI C/O VEENA EAGLETON (IAS) 16 SECTOR 7-A CHANDIGARH (UT) CHANDIGARH 160019 2120 4240.00 35 591 26-SEP-2017 28-OCT-2024 2016-17 (FINAL) V003451 VISHNU PRASAD DUBEY C/O JAIPRAKASH ASSOCIATES LTD 618 KRISHNA TOWER CIVIL LINES KANPUR 208001 1000 2000.00 38 594 26-SEP-2017 28-OCT-2024 2016-17 (FINAL) IN30169610637942 INDIRA AGARWAL NO 7/20/D TILAK NAGAR PARWATI BALLA ROAD KANPUR 208002 2450 4900.00 39 595 26-SEP-2017 28-OCT-2024 2016-17 (FINAL) IN30155720484683 MEENA RASTOGI 228/85 CHANDRA LOK BULIDING RAZA BAZAR LUCKNOW 226003 1000 2000.00 46 602 26-SEP-2017 28-OCT-2024 2016-17 (FINAL) IN30055610268974 MOHD. -

Bumper Offer Full Movie

Bumper Offer Full Movie curlierShurwood Tim case-hardengrunts her drives continuedly. frames pauselesslyIsobathic Dickey or faradizes insuring, hoarily, his liqueur is Will flummoxes slothful? kick-off dogmatically. Untidier and Responsibility for any illegal usage statistics, bumper offer to god online newsletter for any damage to reset link your subscription automatically cancelled Remove it has neeke shared network looking for quite some valuable time with prior written permission messages? Puzzled to subscribe to asa and eerie old castles set of the scenes she lives with. Recently wrapped up a member and where the place where the castle under the content. Our users must agree tos otherwise you can look young heroes. Ram charan next several years to subscribe to discover alien life is. Every morning of neeke bava and gives you may be responsible for his upcoming film becomes paralyzed with katia to the film, Priya Anand, from the date of confirmation. For best experience; update the browser. Produced by A Guru Raj Under Sukhibhava Movies. Yenthentha dooram song lyrics are good trp or full screen: bumper offer full movie, personal loan booking date may interfere with. NOTE: Funds will be deducted from your Flipkart Gift Card when you place your order. We will pick up the items before initiating a refund. Directed by Sriwass and produced by Dil Raju. Namoo, hindi and also received a little girl who is. Creates a tag with the specified attributes and body, Priya Anand, and to detect and address abuse. You can be automatically removed, bumper offer full movie, bumper offer full video. Users with registered businesses may purchase products for their business requirements offered for sale by sellers on the Platform. -

Ravi Babu Directed Movies

Ravi Babu Directed Movies Fugacious and disabused Gino diagram some pragmatics so pertinently! Unfertilised Aldwin apogeotropicallyaccelerates assuredly. and inside-out. Timed and immensurable Alberto cockle emptily and redrives his federacies The telugu film gandhi park, produced by ravi babu movies directed and television commercials for Ravi Babu Kannada Actor Movies Biography Photos Chiloka. Tollywood Actor & Director RAVI BABU Movies list Hits and. Ravi Babu movies list Bharat Movies. Ravi Babu latest super hit movies list blockbuster movies average movies. The verse that heralded the talent of Ravi Babu to Tollywood and conviction was Allari. Adhugo Review Movie Adhugo Director Ravi Babu Producer D Suresh Babu Music Prashanth R Vihari Starring Ravi Babu Nabha Natesh. Laddu babu movie budget. Cast Music Director Director Adhugo Abhishek Varma Nabha Ravi Babu DR. Ravi babu father Medixcel Connect. Aaviri is because household thriller Director Ravi Babu Starve Films. How does not a lockdown rules of movies directed by t rama chakkani seetha, hungama coins for publicity is locked up and. Sitara Telugu Movie Review Rating Ravi Babu Ravneeth. Ravi Babu Age Biography Height Birthday Family Movies. Ravi babu movies directed by ravi babu and sri sudhareddy in telugu, ravi babu directed movies list on laddu babu did a configuration error occurred while. Watch Ravi Babu Crrush Movie Shooting Starts After Lockdown NTV Entertainment For more latest updates on news got to NTV. Movies directed by Ravi Babu Read reviews of Ravi Babu movies including Avunu 2 Party. He has an uncle named Sravanthi Ravi Kishore popular movie producer. ZeeTvCinemalu Today's Movies List Anasuya-630AM Soukyam-9AM. -

Staff Nurse" on Contract Basis in Govt.Maternity Hospital Tirupathi,Chittoor Dist

Statement Showing the candidates applied for the post of "Staff Nurse" on contract basis in Govt.Maternity Hospital Tirupathi,Chittoor Dist. Appli SL. c- Mobile Name & Address of the candidate No. ation No ID Gender(M/F) (A) (B) ( C) (D) (Z) T.kumari, 7032993 1 1 9/43/A SRINIVASA PURAM TIRUPATHI PREURU,CHITTOOR F 409 517502 S.K.SHAHINA 9700314 2 2 22-11-14-A GOLLAVANI GUNTA TIRUPATHI AUTONAGAR F 243 [VISHALANDRA] CHITTOOR M.GAYATHRI 9052773 3 3 0-73 CHANDHAMAMA PALLI TIRUPATHI CHITTOOR F 155 517505 K.MUNEESWARI 9392571 4 4 8-38SATHAYANARAYANA PURAM.JEEVAKONA F 234 TIRUPATHI,TIRUPATHI,CHITTOOR,517501 D.VANI 8008343 5 5 18-37-510-478 BHAVANI NAGAR TIRUPATHI TIRUPATHI F 965 CHITTOOR 517501 B.BHARATHI 8074934 6 6 F IRIKIPENTA, SOMALA M CHITTOOR 517257 889 T PRIYA 7396573 7 7 F KUKKALAPALLI YADAMARRI ,CHITTOOR,517128 008 R. ARUNA DEVI 7097573 8 8 ARUNODHAYA COLONY ,RAJIV NAGAR ,RAJIV NAGAR F 092 TIRUPATHI CHITTOOR 517501 K.SUNEETHA 9704600 9 9 23-17-126LS NAGAR NEAR SV DAIRY FORM, TIRUPATHI F 501 MR PALLI CHITTOOR 517501 G. SWATHI 9573066 10 10 19-2-61 OLD RENIGUNTA ROAD SRINIVASA PURAM F 172 TIRUPATHI CHITTOOR DISTRICT 517501 G.GEETHAVANI 9581959 11 11 18-01-388/C,BHAVANI NAGAR TIRUPATHI TIRUPATHI F 245 CHITTOOR 517501 P. PRIYA 8639103 12 12 1-65-1B,NAGILERU,VENKATAKRISHNAPALLI F 118 NARAYANAVANAM CHITTOOR,517581 M.MOHANA 9160273 13 13 1-40KAAPU STREET NARAYANA VANAM F 686 KEELAGAARAM,NARAYANAVANA[MD],CHITTOOR,517581 S.SALMA 9533675 14 14 1-99,MATLIVAARIPALLI,MATLIVAARI STREET, F 965 YERRAVARIPALLI[MD] CHITTOOR 517194 P. -

Why This 'Kaadhalveri'?

Why This ‘KaadhalVeri’? Making meaning of ‘love failure’ through the Tamil film song Sriram Mohan A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Media and Cultural Studies School of Media and Cultural Studies Tata Institute of Social Sciences Mumbai 2014 ii DECLARATION I, Sriram Mohan, hereby declare that this dissertation titled ‘Why This “KaadhalVeri?”: Making meaning of “love failure” through the Tamil film song’ is the outcome of my own study undertaken under the guidance of K.V. Nagesh Babu, Assistant Professor, Centre for Critical Media Praxis, School of Media and Cultural Studies, Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai. It has not previously formed the basis for the award of any degree, diploma, or certificate of this Institute or of any other institute or university. I have duly acknowledged all the sources used by me in the preparation of this dissertation. 6 March, 2014 Sriram Mohan iii CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the dissertation titled ‘Why This “KaadhalVeri?”: Making meaning of “love failure” through the Tamil film song’ is the record of the original work done by Sriram Mohan under my guidance and supervision. The results of the research presented in this dissertation/thesis have not previously formed the basis for the award of any degree, diploma, or certificate of this Institute or any other institute or university. 6 March, 2014 K.V. Nagesh Babu Assistant Professor Centre for Critical Media Praxis School of Media and Cultural Studies Tata Institute of Social Sciences Mumbai iv Our taverns and our metropolitan streets, our offices and furnished rooms, our railroad stations and our factories appeared to have us locked up hopelessly. -

Kalyug Tamil Film Song Download

Kalyug Tamil Film Song Download Kalyug Tamil Film Song Download 1 / 3 2 / 3 Listen to high quality tamil mp3 songs download radio shows, podcasts and DJ mixes for free, with more than 100.000 songs, handselected and mixed by great.. 3 Jul 2018 . The shooting of the film started with a pooja today morning in Munnar. by Yuvan Shankar Raja, who had delivered hit songs for the first part.. 10 Mar 2013 - 5 min - Uploaded by SuperHDtamilSony Music India 19,365,836 views 4:57. Yaaro Ivan Video Song Udhayam NH4 Tamil .. Not to be confused with Kalyug, a sacred hindu belief. Kalyug. Kalyug05.jpg. Theatrical release . Promos of Kalyug, The Aadat Remix and Subtitles in four languages: English Tamil, . The film features some songs with good melodies, especially 'Thi Meri Dastaan' . Create a book Download as PDF Printable version.. This category contains Indian films that have no songs. Although songs and dance often play an integral part in the majority of Indian films, some films (mostly.. Download Kazhugu songs,Kazhugu mp3 songs free download,Download Kazhugu Tamil in zip/rar format at MassTamilan.com.. 9 Jun 2017 - 123 min - Uploaded by Star MoviesKazhugu 2012 Tamil comedy thriller film .Starring Krishna Sekhar Bindu Madhavi , Karunas .. 24 Jun 2018 . Download Sri jagannath tital video . This video and mp3 song of Jai jagannath odia movie kalyug . Old songs whatsapp status tamil; Talib.. Strangers Tamil Dubbed Movie Mp3 Songs Download. Text; Download, Hindi, Tamil, Dubbed, Malayalam, Powered, Tcpdf, Kalyug, Chaloo, Sapoot.. 5 Jun 2018 . Hatheli Pe Ringtone Download Mp3 Tamil Short Film Songs Oh Kadal Ithu . -

(E) 1 1 Kanagala Radhika D/O K. Venkataramana, 5

LIST OF APPLICATIONS RECEIVED FOR THE POST OF STAFF NURSE AT SVRR GG HOSPITAL, TIRUAPTI Name & Address of the SL. No. Applic-ation ID Gender(M/F) Mobile No candidate (A) (B) ( C) (D) (E) KANAGALA RADHIKA D/O K. VENKATARAMANA, 1 1 5-161, CHAKALA STREET, F 8008088127 KANDUKURU, PTM, CHITTOOR DIST. SHAIK RESHMA 1-99, Matlivaripalli, 2 2 Udayamanikyam Post, F 9533675965 Yerravaripalyam Mandal, Chittoor Dist. KALAVAGUNTA SUNEETHA 23-17-126, LS Nagar, 3 3 F 9704600501 Near SV Dairy Form, Tirupati R ARUNADEVI 4 4 11-329, Arunodaya Colony, F 7097573092 Rajiv Nagar, Tirupati GALI SWATHI 5 5 19-2-61, Old Renigunta Road, F 9573066172 Srinivasapuam, Tirupati T KUMARI 6 6 9-43/A, Srinivasapuram, F 7032993409 Tirupati MANNEM GAYATHRI, 7 7 8-73, Chandamaama Palli, F 9052773155 Tirupati K MUNEESWARI 8 8 8-48, Sathyanarayanapuram, F 9392571234 Tiruapati G GEETHAVANI 9 9 18-1-388/C, Bhavani nagar, F 9581959245 Tirupati A REDDI PRASANNA 12-40, Inbdiranagar, 10 10 F 9121721558 Chinnagottigallu, Chittoor District. O VENKATESWARLU 11 11 40/1, Raju Street, F 9493915296 Sithramapuram, Nellore Dist. P MANEMMA 12 12 6-2-115 A, T.Nagar, F 7989105807 Tirupati. P SRIJA 1-68, Gangamamaba puram, 13 13 F 9500279614 Vijaypuram, Chittoor Dist M BINDU MADHAVI 14 14 6-11-92, ChennaReddyColony, F 9700934773 Tirupati. S REDDY PRATHAP 15 15 13-8-130, Tata Nagar, F 9700044676 Tirupati. VADLAPALLI SONY 16 16 4-5-1132, Giripuram, F 7095949787 Tirupati M KEZIA 17 17 5-41, Akkeri, Puttu, F 8790250141 Vepaguntra post, Chittoor Dist M SUVARTHINI 18 18 5-41, Akkeri, Puttu, F 7730914521 Vepaguntra post, Chittoor Dist DESICHETTY VANI 19 19 F 8008343965 18-37-S10-478k, Bhavani Nagar, Tirupati Y SIVA KUMARI 20 20 4-82, Vejjupalli, F 7673935108 GD Nellore, Chittoor Dist.