331409 Finalreport India Fish

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The First Report of the Malabar Puffer, Carinotetraodon Travancoricus

Journal on New Biological Reports 1(2): 42-46 (2012) ISSN 2319 – 1104 (Online) The first report of the Malabar puffer, Carinotetraodon travancoricus (Hora & Nair, 1941) from the Neyyar wildlife sanctuary with a note on its feeding habit and length-weight relationship G. Prasad*, K. Sabu and P.V. Prathibhakumari Laboratory of Conservation Biology, Department of Zoology, University of Kerala, Kariavattom, Thiruvananthapuram 695 581, Kerala, India (Received on: 20 October, 2012; accepted on: 2 November, 2012) ABSTRACT Carinotetraodon travancoricus, the Malabar puffer fish has been collected and reported for first time from the Kallar stream, Neyyar Wildlife Sanctuary of southern part of Kerala. The food and feeding habit and length-weight relationship of the fish also has been studied and presented. Key words : Carinotetraodon travancoricus, Neyyar Wildlife Sanctuary, Kallar stream, length- weight relationship INTRODUCTION The Western Ghats of India along with Sri Lanka is Carinotetraodon travancoricus commonly considered as one of the biodiversity hotspots of the known as Malabar puffer fish inhabits in freshwater world (Mittermeier et al. 1998; Myers et al. 2000). and estuaries which is endemic to Kerala and This mountain range extends along the west coast of Karnataka (Talwar & Jhingran 1991; Jayaram 1999; India and is crisscrossed with many streams, which Remadevi 2000). Carinotetraodon travancoricus was form the headwaters of several major rivers draining first described from Pamba River by Hora & Nair water to the plains of peninsular India. The Ghats is a (1941). This fish is present in 13 rivers of Kerala critical ecosystem due to its high human population including Chalakudy, Pamba, Periyar, Kabani, pressure (Cincotta et al. -

KERALA SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT PROJECT (KSWMP) with Financial Assistance from the World Bank

KERALA SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT Public Disclosure Authorized PROJECT (KSWMP) INTRODUCTION AND STRATEGIC ENVIROMENTAL ASSESSMENT OF WASTE Public Disclosure Authorized MANAGEMENT SECTOR IN KERALA VOLUME I JUNE 2020 Public Disclosure Authorized Prepared by SUCHITWA MISSION Public Disclosure Authorized GOVERNMENT OF KERALA Contents 1 This is the STRATEGIC ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT OF WASTE MANAGEMENT SECTOR IN KERALA AND ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL MANAGEMENT FRAMEWORK for the KERALA SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT PROJECT (KSWMP) with financial assistance from the World Bank. This is hereby disclosed for comments/suggestions of the public/stakeholders. Send your comments/suggestions to SUCHITWA MISSION, Swaraj Bhavan, Base Floor (-1), Nanthancodu, Kowdiar, Thiruvananthapuram-695003, Kerala, India or email: [email protected] Contents 2 Table of Contents CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION TO THE PROJECT .................................................. 1 1.1 Program Description ................................................................................. 1 1.1.1 Proposed Project Components ..................................................................... 1 1.1.2 Environmental Characteristics of the Project Location............................... 2 1.2 Need for an Environmental Management Framework ........................... 3 1.3 Overview of the Environmental Assessment and Framework ............. 3 1.3.1 Purpose of the SEA and ESMF ...................................................................... 3 1.3.2 The ESMF process ........................................................................................ -

Rain 11 08 2019.Xlsx

Rainfall in 'mm' on 11.08.2019 District River Basin Station Name 11-08-2019 Alappuzha Achencovil Kollakadavu 55.2 Alappuzha Manimala Ambalapuzha 99.3 Alappuzha Muvattupuzha Arookutty 114.4 Alappuzha Muvattupuzha Cherthala 108 Cannanore Anjarakandy Cheruvanchery 96 Cannanore Anjarakandy F.c.s. Pazhassi 93 Cannanore Anjarakandy Kottiyoor 176 Cannanore Anjarakandy Kannavam 72 Cannanore Karaingode Pulingome 167.4 Cannanore Kuppam Alakkode 148.6 Cannanore Peruvamba Kaithaprem 116.2 Cannanore Peruvamba Olayampadi 144.6 Cannanore Ramapuram Cheruthazham 70.2 Cannanore Anjarakandy Maloor 104 Cannanore Valapattanam Mangattuparamba 58.6 Cannanore Anjarakandy Nedumpoil 77.2 Cannanore Valapattanam Palappuzha 80 Cannanore Valapattanam Payyavoor 140 Cannanore Kuppam Alakkode 148.6 Cannanore Valapattanam Thillenkeri 121 Ernakulam Muvattupuzha Piravam 87.2 Ernakulam Periyar Aluva 112.5 Ernakulam Periyar Boothathankettu 79.6 Ernakulam Periyar Keerampara 63.2 Ernakulam Periyar Neriyamangalam 69.8 Idukki Manimala Boyce estate 47 Idukki Muvattupuzha Vannapuram 54.3 Idukki Pambar Marayoor 5.6 Idukki Periyar Chinnar 37 Idukki Periyar FCS Painavu 32.4 Idukki Periyar Kumali 27 Idukki Periyar Nedumkandam 23.8 Idukki Periyar Vandanmedu 34.8 Kasaragod Chandragiri Vidhyanagar 161.8 Kasaragod Chandragiri Kalliyot 142.3 Kasaragod Chandragiri Padiyathadukka 126.4 Kasaragod Karaingode Kakkadavue(cheemeni)fcs 141.8 Kasaragod Manjeswar Manjeswaram 74 Kasaragod Morgal Madhur 145.2 Kasaragod Nileswar Erikkulam 127.4 Kasaragod Shiriya Paika 137 Kasaragod Uppala Uppala 90.5 -

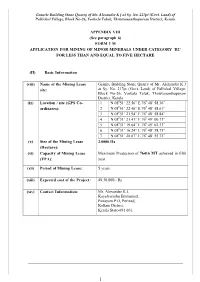

Form 1 M Application for Mining of Minor Minerals Under Category ‘B2’ for Less Than and Equal to Five Hectare

Granite Building Stone Quarry of Mr. Alexander K J at Sy. No. 217pt (Govt. Land) of Pallickal Village, Block No-26, Varkala Taluk, Thiruvananthapuram District, Kerala APPENDIX VIII (See paragraph 6) FORM 1 M APPLICATION FOR MINING OF MINOR MINERALS UNDER CATEGORY ‘B2’ FOR LESS THAN AND EQUAL TO FIVE HECTARE (II) Basic Information (viii) Name of the Mining Lease Granite Building Stone Quarry of Mr. Alexander K J site: at Sy. No. 217pt (Govt. Land) of Pallickal Village, Block No-26, Varkala Taluk, Thiruvananthapuram District, Kerala 0 0 (ix) Location / site (GPS Co- 1 N 08 51’ 22.56” E 76 48’ 58.36” 0 0 ordinates): 2 N 08 51’ 22.46” E 76 48’ 58.61” 0 0 3 N 08 51’ 21.94” E 76 48’ 58.84” 0 0 4 N 08 51’ 21.41” E 76 49’ 00.73” 0 0 5 N 08 51’ 19.64” E 76 49’ 02.33” 0 0 6 N 08 51’ 16.24” E 76 48’ 58.75” 0 0 7 N 08 51’ 20.07” E 76 48’ 55.72” (x) Size of the Mining Lease 2.0000 Ha (Hectare): (xi) Capacity of Mining Lease Maximum Production of 76416 MT achieved in fifth (TPA): year. (xii) Period of Mining Lease: 5 years (xiii) Expected cost of the Project: 49,30,000/- Rs (xiv) Contact Information: Mr. Alexander K J, Kayalvarathu Emmanuel, Panayam P.O, Perinad, Kollam District, Kerala State-691 601. 1 Granite Building Stone Quarry of Mr. Alexander K J at Sy. No. 217pt (Govt. -

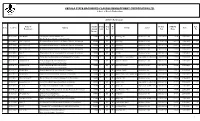

2015-16 Term Loan

KERALA STATE BACKWARD CLASSES DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION LTD. A Govt. of Kerala Undertaking KSBCDC 2015-16 Term Loan Name of Family Comm Gen R/ Project NMDFC Inst . Sl No. LoanNo Address Activity Sector Date Beneficiary Annual unity der U Cost Share No Income 010113918 Anil Kumar Chathiyodu Thadatharikathu Jose 24000 C M R Tailoring Unit Business Sector $84,210.53 71579 22/05/2015 2 Bhavan,Kattacode,Kattacode,Trivandrum 010114620 Sinu Stephen S Kuruviodu Roadarikathu Veedu,Punalal,Punalal,Trivandrum 48000 C M R Marketing Business Sector $52,631.58 44737 18/06/2015 6 010114620 Sinu Stephen S Kuruviodu Roadarikathu Veedu,Punalal,Punalal,Trivandrum 48000 C M R Marketing Business Sector $157,894.74 134211 22/08/2015 7 010114620 Sinu Stephen S Kuruviodu Roadarikathu Veedu,Punalal,Punalal,Trivandrum 48000 C M R Marketing Business Sector $109,473.68 93053 22/08/2015 8 010114661 Biju P Thottumkara Veedu,Valamoozhi,Panayamuttom,Trivandrum 36000 C M R Welding Business Sector $105,263.16 89474 13/05/2015 2 010114682 Reji L Nithin Bhavan,Karimkunnam,Paruthupally,Trivandrum 24000 C F R Bee Culture (Api Culture) Agriculture & Allied Sector $52,631.58 44737 07/05/2015 2 010114735 Bijukumar D Sankaramugath Mekkumkara Puthen 36000 C M R Wooden Furniture Business Sector $105,263.16 89474 22/05/2015 2 Veedu,Valiyara,Vellanad,Trivandrum 010114735 Bijukumar D Sankaramugath Mekkumkara Puthen 36000 C M R Wooden Furniture Business Sector $105,263.16 89474 25/08/2015 3 Veedu,Valiyara,Vellanad,Trivandrum 010114747 Pushpa Bhai Ranjith Bhavan,Irinchal,Aryanad,Trivandrum -

Understanding REPORT of the WESTERNGHATS ECOLOGY EXPERT PANEL

Understanding REPORT OF THE WESTERNGHATS ECOLOGY EXPERT PANEL KERALA PERSPECTIVE KERALA STATE BIODIVERSITY BOARD Preface The Western Ghats Ecology Expert Panel report and subsequent heritage tag accorded by UNESCO has brought cheers to environmental NGOs and local communities while creating apprehensions among some others. The Kerala State Biodiversity Board has taken an initiative to translate the report to a Kerala perspective so that the stakeholders are rightly informed. We need to realise that the whole ecosystem from Agasthyamala in the South to Parambikulam in the North along the Western Ghats in Kerala needs to be protected. The Western Ghats is a continuous entity and therefore all the 6 states should adopt a holistic approach to its preservation. The attempt by KSBB is in that direction so that the people of Kerala along with the political decision makers are sensitized to the need of Western Ghats protection for the survival of themselves. The Kerala-centric report now available in the website of KSBB is expected to evolve consensus of people from all walks of life towards environmental conservation and Green planning. Dr. Oommen V. Oommen (Chairman, KSBB) EDITORIAL Western Ghats is considered to be one of the eight hottest hot spots of biodiversity in the World and an ecologically sensitive area. The vegetation has reached its highest diversity towards the southern tip in Kerala with its high statured, rich tropical rain fores ts. But several factors have led to the disturbance of this delicate ecosystem and this has necessitated conservation of the Ghats and sustainable use of its resources. With this objective Western Ghats Ecology Expert Panel was constituted by the Ministry of Environment and Forests (MoEF) comprising of 14 members and chaired by Prof. -

Final Project Completion Report

CEPF SMALL GRANT FINAL PROJECT COMPLETION REPORT Organization Legal Name: Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS) Status of freshwater fishes in the Sahyadri-Konkan Corridor: Project Title: diversity, distribution and conservation assessments in Raigad. Date of Report: 08-05-2015 Mr. Unmesh Gajanan Katwate Report Author and Contact Dr. Rupesh Raut Information CEPF Region: Western Ghats & Sri Lanka Hotspot (Sahyadri-Konkan Corridor) CEPF Strategic Direction 2: Improve the conservation of globally threatened species through systematic conservation planning and action. Grant Amount: $ 18,366.36 Project Dates: 1st July 2013 to 31st January 2015 Implementation Partners for this Project (please explain the level of involvement for each partner): Dr. Neelesh Dahanukar Indian Institute of Science, Education and Research (IISER) Involvement in field study, species identification, publication of project results in peer reviewed scientific journals and setting conservation priorities for the fishes of Raigad District. Systematics and genetic study of freshwater fishes collected during project period. Dr. Rajeev Raghavan Department of Fisheries Resource Management Kerala University of Fisheries and Ocean Studies (KUFOS), Kochi, India Conservation Research Group (CRG), St. Albert’s College, Kochi, Kerala, India Involvement in fish study, species identification, and publication of project results in peer reviewed journals. Contribution in systematic study of fishes of Raigad District and implementing regional conservation plans. Dr. Mandar Paingankar Department of Zoology, University of Pune Involvement in field surveys, fishing expeditions, species identification and publication of project results in scientific journals. Contribution in molecular study of fishes of the Raigad District. Dr. Sanjay Molur Zoo Outreach Organization (ZOO) Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu 641 035, India Involvement in developing strategic conservation plans for fishes in northern Western Ghats through IUCN Red List assessment of fishes. -

The Status of the Forest Rights Act (FRA) in Protected Areas of India a Draft Report Summary

The Status of the Forest Rights Act (FRA) in Protected Areas of India A Draft Report Summary Background and Objectives of the study The Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Rights) Act (more commonly referred to as the Forest Rights Act or FRA) was enacted in 2006 and came into force in 2008 with the drafting of its Rules. The Act aims at addressing the “historic injustice” that was meted out to the forest dwellers by recognising forest land, resources, and resource management and conservation rights of the forest dwelling communities. However, the implementation of the Act in general and especially in Protected Areas (PAs) has been negligible and tardy. The objective of this report is to enhance and contribute towards understanding the status of implementation of FRA in Protected Areas (PAs), particularly to assess: a) Extent to which Individual Forest Rights (IFRs) right to live in and cultivate, Community Forest Rights (CRs) or right to use, harvest and sell forest produce and Community Forest Resource (CFR) Rights or right to protect, regenerate, or conserve or manage forests within the customary boundary of a village (Section 3 (1)i of FRA); b) Extent to which have the provisions of co-existence as per Section 38V(4)ii of Wild Life Protection (Amendment) Act (WLPA) 2006 has been implemented. To what extent have communities been able to formulate strategies for wildlife protection under section 5 of FRA and drafted conservation and management plans as per Rule 4e. Extent to which these plans and strategies have been incorporated in the overall PA management plans; c) Extent to which the provisions related to relocation under the WLPA Section 38 V 5 (i to vi) and Section 4 (2) a to f of FRA have been implemented in PAs. -

Scheduled Caste Sub Plan (Scsp) 2014-15

Government of Kerala SCHEDULED CASTE SUB PLAN (SCSP) 2014-15 M iiF P A DC D14980 Directorate of Scheduled Caste Development Department Thiruvananthapuram April 2014 Planng^ , noD- documentation CONTENTS Page No; 1 Preface 3 2 Introduction 4 3 Budget Estimates 2014-15 5 4 Schemes of Scheduled Caste Development Department 10 5 Schemes implementing through Public Works Department 17 6 Schemes implementing through Local Bodies 18 . 7 Schemes implementing through Rural Development 19 Department 8 Special Central Assistance to Scheduled C ^te Sub Plan 20 9 100% Centrally Sponsored Schemes 21 10 50% Centrally Sponsored Schemes 24 11 Budget Speech 2014-15 26 12 Governor’s Address 2014-15 27 13 SCP Allocation to Local Bodies - District-wise 28 14 Thiruvananthapuram 29 15 Kollam 31 16 Pathanamthitta 33 17 Alappuzha 35 18 Kottayam 37 19 Idukki 39 20 Emakulam 41 21 Thrissur 44 22 Palakkad 47 23 Malappuram 50 24 Kozhikode 53 25 Wayanad 55 24 Kaimur 56 25 Kasaragod 58 26 Scheduled Caste Development Directorate 60 27 District SC development Offices 61 PREFACE The Planning Commission had approved the State Plan of Kerala for an outlay of Rs. 20,000.00 Crore for the year 2014-15. From the total State Plan, an outlay of Rs 1962.00 Crore has been earmarked for Scheduled Caste Sub Plan (SCSP), which is in proportion to the percentage of Scheduled Castes to the total population of the State. As we all know, the Scheduled Caste Sub Plan (SCSP) is aimed at (a) Economic development through beneficiary oriented programs for raising their income and creating assets; (b) Schemes for infrastructure development through provision of drinking water supply, link roads, house-sites, housing etc. -

District Functionaries

DISTRICT FUNCTIONARIES Kollam District DESIGNATION OFFICE PHONE/FAX MOBILE E-MAIL ID DISTRICT COLLECTOR 0474 2794900 9447795500 [email protected] DISTRICT POLICE CHIEF, KOLLAM 0474 2764422 9497996984 [email protected] CITY DISTRICT POLICE CHIEF, KOLLAM 0474 2450168 9497996908 [email protected] RURAL DY. COLLECTOR (ELECTION) 0474 2798290 8547610029 JS (ELECTION) 9496409857 [email protected] 0474 2796675 ELECTION ASSISTANT 9846110055 CORPORATION NO & NAME OF LB RO, ERO, SEC DESIGNATION OFFICE No. MOBILE E-MAIL ID RO (Wards 01 - 28) Deputy Director, Economics & 0474 2793418 9495439709 [email protected] Statistics, Kollam Assistant Conservator of Forests RO (Wards 01 - 28) 0474 2748976 9447979132 [email protected] (Social Forestry), Kollam C 02 KOLLAM CORPORATION ERO Additional Secretary, Kollam 0474 2749860 9447964511 Corporation [email protected] SECRETARY Secretary, Kollam Corporation 0474 2742724 9447413433 MUNICIPALITIES RO, ERO & OFFICE NO & NAME OF LB DESIGNATION MOBILE E-MAIL ID Secretary PHONE/FAX District Soil Conservation Officer, RO 0474 2768816 9447632532 [email protected] Kollam M 05 Paravur Municipality ERO Secretary, Paravur Municipality 0474 2512340 8281286929 [email protected] Divisional Forest Officer, Timbersales RO 0475 2222617 9847021389 [email protected] M 06 Punalur Municipality Division, Punalur ERO Secretary, Punalur Municipality 0475 2222683 9037568221 [email protected] Joint Director of Co operative Audit, RO 0474 2794923 9048791068 jdaklm@co_op.kerala.gov.in Kollam -

State City Hospital Name Address Pin Code Phone K.M

STATE CITY HOSPITAL NAME ADDRESS PIN CODE PHONE K.M. Memorial Hospital And Research Center, Bye Pass Jharkhand Bokaro NEPHROPLUS DIALYSIS CENTER - BOKARO 827013 9234342627 Road, Bokaro, National Highway23, Chas D.No.29-14-45, Sri Guru Residency, Prakasam Road, Andhra Pradesh Achanta AMARAVATI EYE HOSPITAL 520002 0866-2437111 Suryaraopet, Pushpa Hotel Centre, Vijayawada Telangana Adilabad SRI SAI MATERNITY & GENERAL HOSPITAL Near Railway Gate, Gunj Road, Bhoktapur 504002 08732-230777 Uttar Pradesh Agra AMIT JAGGI MEMORIAL HOSPITAL Sector-1, Vibhav Nagar 282001 0562-2330600 Uttar Pradesh Agra UPADHYAY HOSPITAL Shaheed Nagar Crossing 282001 0562-2230344 Uttar Pradesh Agra RAVI HOSPITAL No.1/55, Delhi Gate 282002 0562-2521511 Uttar Pradesh Agra PUSHPANJALI HOSPTIAL & RESEARCH CENTRE Pushpanjali Palace, Delhi Gate 282002 0562-2527566 Uttar Pradesh Agra VOHRA NURSING HOME #4, Laxman Nagar, Kheria Road 282001 0562-2303221 Ashoka Plaza, 1St & 2Nd Floor, Jawahar Nagar, Nh – 2, Uttar Pradesh Agra CENTRE FOR SIGHT (AGRA) 282002 011-26513723 Bypass Road, Near Omax Srk Mall Uttar Pradesh Agra IIMT HOSPITAL & RESEARCH CENTRE Ganesh Nagar Lawyers Colony, Bye Pass Road 282005 9927818000 Uttar Pradesh Agra JEEVAN JYOTHI HOSPITAL & RESEARCH CENTER Sector-1, Awas Vikas, Bodla 282007 0562-2275030 Uttar Pradesh Agra DR.KAMLESH TANDON HOSPITALS & TEST TUBE BABY CENTRE 4/48, Lajpat Kunj, Agra 282002 0562-2525369 Uttar Pradesh Agra JAVITRI DEVI MEMORIAL HOSPITAL 51/10-J /19, West Arjun Nagar 282001 0562-2400069 Pushpanjali Hospital, 2Nd Floor, Pushpanjali Palace, -

Patterns of Discovery of Birds in Kerala Breeding of Black-Winged

Vol.14 (1-3) Jan-Dec. 2016 newsletter of malabar natural history society Akkulam Lake: Changes in the birdlife Breeding of in two decades Black-winged Patterns of Stilt Discovery of at Munderi Birds in Kerala Kadavu European Bee-eater Odonates from Thrissur of Kadavoor village District, Kerala Common Pochard Fulvous Whistling Duck A new duck species - An addition to the in Kerala Bird list of - Kerala for subscription scan this qr code Contents Vol.14 (1-3)Jan-Dec. 2016 Executive Committee Patterns of Discovery of Birds in Kerala ................................................... 6 President Mr. Sathyan Meppayur From the Field .......................................................................................................... 13 Secretary Akkulam Lake: Changes in the birdlife in two decades ..................... 14 Dr. Muhamed Jafer Palot A Checklist of Odonates of Kadavoor village, Vice President Mr. S. Arjun Ernakulam district, Kerala................................................................................ 21 Jt. Secretary Breeding of Black-winged Stilt At Munderi Kadavu, Mr. K.G. Bimalnath Kattampally Wetlands, Kannur ...................................................................... 23 Treasurer Common Pochard/ Aythya ferina Dr. Muhamed Rafeek A.P. M. A new duck species in Kerala .......................................................................... 25 Members Eurasian Coot / Fulica atra Dr.T.N. Vijayakumar affected by progressive greying ..................................................................... 27