In Search of the Standard Canadian English

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Meter Greeters

Journal of Applied Communications Volume 59 Issue 2 Article 3 The Meter Greeters C. Hamilton Kenney Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/jac This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Kenney, C. Hamilton (1976) "The Meter Greeters," Journal of Applied Communications: Vol. 59: Iss. 2. https://doi.org/10.4148/1051-0834.1951 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Applied Communications by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Meter Greeters Abstract The United States and Canada became meter greeters away back in the 1800's. The U.S. Congress passed an act in 1866 legalizing the metric system for weights and measures use, and metric units were on the law books of the Dominion of Canada in 1875. This article is available in Journal of Applied Communications: https://newprairiepress.org/jac/vol59/iss2/3 Kenney: The Meter Greeters The Meter Greeters C. Hamilton Kenney The United States and Canada became meter greeters away back in the 1800's. The U.S. Congress passed an act in 1866 legalizing the metric system for weights and measures use, and metric units were on the law books of the Dominion of Canada in 1875. The U.S. A. was a signatory to the Treaty of the Meter l signed in Paris, France. in 1875, establishing the metric system as an international measurement system, but Canada did not become a signatory nation until 1907. -

FLIGHTS (Cal 270) 10.50 (Cal 280) 12.25 (Cal 170-345) Price Varies Cabernet Sauvignon, Paso Robles STAG's LEAP WINE CELLARS HANDS of TIME Goblet Only

23 OUNCE ASK ABOUT PUB GLASS ADDITIONAL DRAFT $2 MORE SELECTIONS beer GOBLETS l PINTs l pub glass l HALF YARDS PINT or 23oz HALF CRISP • REFRESHING GOBLET PUB GLASS YARD BOTTLES • CANS HOUSE BEERS pint or goblet (cal 200) • pub glass (cal 290) • half yard (cal 410) OMISSION PALE ALE (cal 180) 6.00 5.8% • gluten-sensitive • or HOUSE GOLDEN PILSNER 7.00 9.00 15.00 4.8% • pilsner • fort collins, co (cal 100) 6.00 OMISSION ULTIMATE LIGHT 4.2% • gluten-sensitive • or STELLA ARTOIS 6.50 8.50 14.00 5.2% • pilsner • belgium HEINEKEN 0.0 (cal 70) 6.00 0.0% • zero alcohol • netherlands STONE TROPIC OF THUNDER 7.75 9.75 16.50 5.8% • hoppy lager • escondido, ca LAGUNITAS HOPPY REFRESHER (cal 0) 6.00 0.0% • zero alcohol • ca PINT or 23oz HALF IPA • HOPPY GOBLET PUB GLASS YARD pint or goblet (cal 270) • pub glass (cal 390) • half yard (cal 550) PINT or 23oz HALF HOUSE IPA 6.00 8.00 13.00 GOBLET PUB GLASS YARD 6.2% • india pale ale • escondido, ca wine 6oz 9oz Bottle pint or goblet (cal 200) • pub glass (cal 290) • half yard (cal 410) YARD HOUSE 23RD ANNIVERSARY: SPARKLING + WHITE + ROSÉ HOUSE GOLDEN PILSNER 7.00 9.00 15.00 NOBLE PURSUIT 7.75 9.75 16.50 6.9% • india pale ale • fort collins, co • • 4.8% pilsner fort collins, co 6oz (cal 150) • 9oz (cal 220) • bottle (cal 630) LAGUNITAS SUPER CLUSTER 8.00 − − 6.00 8.00 13.00 HOUSE HONEY BLONDE 8.0% • imperial ipa • petaluma, ca RIONDO 9.25 - 46.00 4.9% • honey beer • escondido, ca (5.25oz, cal 130) prosecco, veneto LIQUID COMPASS 8.25 − − HOUSE WHITE ALE 7.00 9.00 15.00 8.5% • imperial ipa • escondido, -

PINT: Probabilistic In-Band Network Telemetry

PINT: Probabilistic In-band Network Telemetry Ran Ben Basat Sivaramakrishnan Ramanathan Yuliang Li Harvard University University of Southern California Harvard University [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Gianni Antichi Minlan Yu Michael Mitzenmacher Queen Mary University of London Harvard University Harvard University [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT 42], fast reroute [47], and path tracing [36]. A significant recent Commodity network devices support adding in-band telemetry mea- advance is provided by the In-band Network Telemetry (INT) [75]. surements into data packets, enabling a wide range of applications, INT allows switches to add information to each packet, such as including network troubleshooting, congestion control, and path switch ID, link utilization, or queue status, as it passes by. Such tracing. However, including such information on packets adds sig- telemetry information is then collected at the network egress point nificant overhead that impacts both flow completion times and upon the reception of the packet. application-level performance. INT is readily available in programmable switches and network in- We introduce PINT, an in-band network telemetry framework terface cards (NICs) [8, 14, 58, 85], enabling an unprecedented level that bounds the amount of information added to each packet. PINT of visibility into the data plane behavior and making this technology encodes the requested data on multiple packets, allowing per-packet attractive for real-world deployments [16, 46]. A key drawback of overhead limits that can be as low as one bit. We analyze PINT and INT is the overhead on packets. -

Measures and Conversion Chart Pesticide Storage

Conversions and Pesticide Storage 63 MEASURES AND CONVERSION CHART Prepared by Hilary A. Sandler Liquid Measures Length and Area Conversions 1 oz = 2 tablespoons = 6 teaspoons = 29.6 ml 1 acre = 43,560 sq. ft = 0.405 hectares 1 cup = 8 oz 1 hectare = 2.47 acres 1 pint = 2 cups = 16 oz 1 meter = 1.09 yards = 3.28 feet = 39.4 inches 1 quart = 2 pints = 4 cups = 32 oz 1 yard = 3 feet = 36 inches = 0.914 meters 1 gallon = 4 quarts = 8 pints = 16 cups = 128 oz 1 cm = 0.39 inches 1 cup = 237 ml 1 inch = 2.54 cm 1 pint = 473 ml = 0.473 liters 1 rod = 16.5 ft 1 quart = 946 ml = 0.946 liters 1 sq. rod = 272.2 sq. ft 1 gallon = 3.78 liters = 3,785 ml 1 square meter = 10.76 square feet 1 acre-foot water = 326,000 gallons 1 cubic meter = 35.29 cubic feet = 1.30 cubic yards 0.1 inch water = 2717 gallons 1 inch layer of sand per acre = 134 cubic yards Mass Conversions Other Conversions 1 oz = 28.4 grams pt/A * 0.473 = liters/A 1 lb = 454 g = 0.454 kg pt/A * 1.167 = liters/ha 1 kg = 2.2 lb = 35.2 oz lb/A * 0.454 = kg/A lb/A * 1.12 = kg/ha gal/A * 3.78 = liter/A Temperature Conversions gal/A * 9.33 = liter/ha °F = (9/5 °C) + 32 (guesstimate: double °C, add 30) ton/A * 2,245 = kg/ha °C = 5/9 (°F-32) bbl/A * 0.112 = Mg/ha 2 g/ft * 0.958= bbl/A PESTICIDE STORAGE GUIDELINES Prepared by Hilary A. -

Imperial Units

Imperial units From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search This article is about the post-1824 measures used in the British Empire and countries in the British sphere of influence. For the units used in England before 1824, see English units. For the system of weight, see Avoirdupois. For United States customary units, see Customary units . Imperial units or the imperial system is a system of units, first defined in the British Weights and Measures Act of 1824, later refined (until 1959) and reduced. The system came into official use across the British Empire. By the late 20th century most nations of the former empire had officially adopted the metric system as their main system of measurement. The former Weights and Measures office in Seven Sisters, London. Contents [hide] • 1 Relation to other systems • 2 Units ○ 2.1 Length ○ 2.2 Area ○ 2.3 Volume 2.3.1 British apothecaries ' volume measures ○ 2.4 Mass • 3 Current use of imperial units ○ 3.1 United Kingdom ○ 3.2 Canada ○ 3.3 Australia ○ 3.4 Republic of Ireland ○ 3.5 Other countries • 4 See also • 5 References • 6 External links [edit] Relation to other systems The imperial system is one of many systems of English or foot-pound-second units, so named because of the base units of length, mass and time. Although most of the units are defined in more than one system, some subsidiary units were used to a much greater extent, or for different purposes, in one area rather than the other. The distinctions between these systems are often not drawn precisely. -

Imperial Units of Measure

Imperial Units of Measure So far we have looked at metric units of measure, but you may have spotted that these are not the only units of measurement that we use. For example, you might buy your milk in pints, or measure a journey in miles. These are some examples of imperial units of measure, which we need to be familiar with. What is the imperial system? Do not panic! You will not be expected to remember the measurements needed to convert between metric and Take a look at this video to start your imperial units. You will always be given the numbers you investigation. need to convert. https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/topics/z4nsgk7/ articles/zwbndxs See if you can find these units of measure being used anywhere around your house. You will spot this symbol being used when looking at imperial and metric measures. This symbol means ‘approximately’ or ‘approximately equal to’. It is hard to be exact when using two different systems of measurement and we often use rounding to make the calculations easier. Using Imperial Units of Measure Let’s start by looking at length I’m going to use a bar model to help me solve these conversions. If I know that 1 inch is approximately 2.5 centimetres, I think I’m going to need to be counting up in 2.5 10 cm 2.5 2.5 2.5 2.5 I have used the conversion given to me, to work out that 4inches is approximately 10cm. I know that 16 is 4 lots of 4 (4x4) So, I need to know what 4 lots of 10 is (4x10) 16 inches is approximately 40cm 15inches is 1 inch less than 16. -

2,4-D Amine 4 Herbicide

SPECIMEN LABEL 2,4-D AMINE 4 HERBICIDE For selective control of many broadcast weeds in certain crops, ACTIVE INGREDIENT: Dimethylamine salt of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid* . 46.8% including, cereal grains (wheat, barley, millet, oats and rye), OTHER INGREDIENTS: . 53.2% corn (field corn, popcorn and sweet corn), fallow land and crop stubble, rice, sorghum (grain and forage sorghum), soybeans TOTAL:. 100.0% (preplant burndown application only); forests; rangeland and *Equivalent to 38.9% of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid or 3.8 lb./gal. Isomer specific by AOAC Method. established grass pastures, including Conservation Reserve EPA Reg. No. 42750-19 Program (CRP) acres; non-cropland; grasses grown for seed or KEEP OUT OF REACH OF CHILDREN sod, ornamental turf; and aquatic areas. DANGER – PELIGRO Si usted no entiende la etiqueta, busque a alguien para que se la explique a usted en detalle. (If you do not understand this label, find someone to explain it to you in detail.) Manufactured By: FIRST AID IF IN EYES • Hold eye open and rinse slowly and gently with water for 15-20 minutes. Albaugh, LLC • Remove contact lenses, if present, after the first 5 minutes, then continue rinsing eye. • Call a poison control center or doctor for treatment advice. Ankeny, Iowa 50021 IF SWALLOWED • Call a poison control center or doctor immediately for treatment advice. • Have person sip a glass of water if able to swallow. • Do not induce vomiting unless told to do so by the poison control center or doctor. • Do not give anything by mouth to an unconscious person. IF ON SKIN OR • Take off contaminated clothing. -

How to Speak (And Understand) 'Canajun', Eh

how to speak (and understand) ‘canajun’, eh Contents 4. Booze 1. Phrases 5. Food 2. Money 6. Signs (road and business) 3. Sales Tax 7. Functioning in English/Using your French Canadians and Americans often assume that we speak the same language—English. But, as I soon discovered when I went to Grad School in the United States, there are some differences that can cause confusion. And, while Canadians have become familiar with, and often use, American terms due to the influence of American film and TV, Canadian English may be less known to Americans. So, with a little help from an ASTR document entitled “Canadian vs. American English”, here are some hints to help you navigate the distance between our two versions of the Mother Tongue. Let us begin with that iconic Canadian interjection, “eh” (pronounced like the first letter of the alphabet). It has been argued that “eh” has ten different meanings, the most common ones being “pardon?” (as in a request for repetition) and as a tag, as in “I’m Canadian, eh.” I won’t go into all of them here, but two others you may hear are the “narrative eh” (“I’m going to ATHE, eh, it’s in Montreal this year, eh, and it should be fabulous, eh!”) and as a reinforcement of an exclamation (“How about that fabulous ATHE Conference in Montreal, eh!”). Here are some other “translations” to help you out. American Word or Phrase Canadian Equivalent Napkin Serviette Canadians will use both terms, but Serviette generally refers to a paper napkin Check Bill In Canada, we pay bills with a cheque. -

Unit Conversions

Unit Conversions EQUIVALENCY UNIT CONVERSION FACTOR Length 1 foot = 12 inches ____1 ft or ____12 in 12 in 1 ft 1 yd ____3 ft 1 yard = 3 feet ____ or 3 ft 1 yd 1 mile = 5280 feet ______1 mile or ______5280 ft 5280 ft 1 mile Time 1 min 60 sec 1 minute = 60 seconds ______ or ______ 60 sec 1 min 1 hr 60 min 1 hour = 60 minutes ______ or ______ 60 min 1 hr 1 day 24 hr 1 day = 24 hours ______ or ______ 24 hr 1 day ______1 week ______7 days 1 week = 7 days or 7 days 1 week Volume (Capacity) 1 cup = 8 fluid ounces ______1 cup or ______8 fl oz 8 fl oz 1 cup 1 pt 2 cups 1 pint = 2 cups ______ or ______ 2 cups 1 pt ______1 qt 1 quart = 2 pints or ______2 pts 2 pts 1 qt ______1 gal ______4 qts 1 gallon = 4 quarts or 4 qts 1 gal Weight 1 pound = 16 ounces ______1 lb or ______16 oz 16 oz 1 lb 1 ton 2000 lbs 1 ton = 2000 pounds _______ or _______ 2000 lbs 1 ton How to Make a Unit Conversion STEP1: Select a unit conversion factor. Which unit conversion factor we use depends on the units we start with and the units we want to end up with. units we want Numerator Unit conversion factor: units to eliminate Denominator For example, if we want to convert minutes into seconds, we want to eliminate minutes and end up with seconds. Therefore, we would use 60 sec . -

Metrication Problems in the Construction Codes and Standards Sector

Lef©r©nce NBS Pubii - cations i vt NBS TECHNICAL NOTE 915 v ^&^ J 0ffBM Of NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS 1 The National Bureau of Standards was established by an act of Congress March 3, 1901. The Bureau's overall goal is to strengthen and advance the Nation's science and technology and facilitate their effective application for public benefit. To this end, the Bureau conducts research and provides: (1) a basis for the Nation's physical measurement system, (2) scientific and technological services for industry and government, (3) a technical basis for equity in trade, and (4) technical services to promote public safety. The Bureau consists of the Institute for Basic Standards, the Institute for Materials Research, the Institute for Applied Technology, the Institute for Computer Sciences and Technology, and the Office for Information Programs. THE INSTITUTE FOR BASIC STANDARDS provides the central basis within the United States of a complete and consistent system of physical measurement; coordinates that system with measurement systems of other nations; and furnishes essential services leading to accurate and uniform physical measurements throughout the Nation's scientific community, industry, and commerce. The Institute consists of the Office of Measurement Services, the Office of Radiation Measurement and the following Center and divisions: Applied Mathematics — Electricity — Mechanics — Heat — Optical Physics — Center for Radiation Research: Nuclear Sciences; Applied Radiation — Laboratory Astrophysics - — Cryogenics ~ — Electromagnetics " — Time and Frequency ". THE INSTITUTE FOR MATERIALS RESEARCH conducts materials research leading to improved methods of measurement, standards, and data on the properties of well-characterized materials needed by industry, commerce, educational institutions, and Government: provides advisory and research services to other Government agencies; and develops, produces, and distributes standard reference materials. -

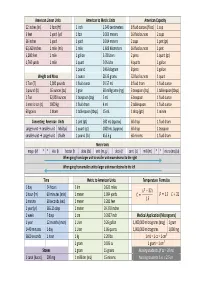

Conversion Chart Revised

American Linear Units American to Metric Units American Capacity 12 inches (in) 1 foot (ft) 1 inch 2.540 centimeters 8 fluid ounces (fl oz) 1 cup 3 feet 1 yard (yd) 1 foot 0.305 meters 16 fluid ounces 2 cups 36 inches 1 yard 1 yard 0.914 meters 2 cups 1 pint (pt) 63,360 inches 1 mile (mi) 1 mile 1.609 kilometers 16 fluid ounces 1 pint 5,280 feet 1 mile 1 gallon 3.78 Liters 2 pints 1 quart (qt) 1,760 yards 1 mile 1 quart 0.95 Liter 4 quarts 1 gallon 1 pound 0.45 kilogram 8 pints 1 gallon Weight and Mass 1 ounce 28.35 grams 32 fluid ounces 1 quart 1 T on (T) 2,000 pounds 1 fluid ounce 29.57 mL 8 fluid dram 1 fluid ounce 1 pound (lb) 16 ounces (oz) 1 grain 60 milligrams (mg) 3 teaspoon (tsp) 1 tablespoon (tbsp) 1 Ton 32,000 ounces 1 teaspoon (tsp) 5 mL 6 teaspoon 1 fluid ounce 1 metric ton (t) 1000 kg 1 fluid dram 4 mL 2 tablespoon 1 fluid ounce 60 grains 1 dram 1 tablespoon (tbsp) 15 mL 1 drop (gtt) 1 minim Converting American Units 1 pint (pt) 500 mL (approx) 60 drop 1 fluid dram Larger unit → smaller unit Multiply 1 quart (qt) 1000 mL (approx) 60 drop 1 teaspoon smaller unit → Larger unit Divide 1 pound (lb) 453.6 g 60 minims 1 fluid dram Metric Units mega (M) * * kilo (k) hector (h) deka (da) unit (m, g, L) deci (d) centi (c) milli (m) * * micro (mc) (u) When going from larger unit to smaller unit move decimal to the right cimal to the left When going from smaller unit to larger unit move de Time Metric to American Units Temperature Formulas 1 day 24 hours 1 km 0.621 miles ʚ̀ Ǝ 32 ʛ 1 hour (hr) 60 minutes (min) 1 meter 1.094 yards ̽ -

Cylindrical English Wine and Beer Bottles 1735-1850

Cylindrical English Wine and Beer Bottles 1735-1850 Olive R. Jones Studies in Archaeology Architecture and History National Historic Parks and Sites Branch Environment Canada - Parks ©Minister of Supply and Services Canada 1986. Available in Canada through authorized bookstore agents and other bookstores, or by mail from the Canadian Government Publishing Centre, Supply and Services Canada, Hull, Quebec, Canada KIA OS9. L'original francais s'intitule Les bouteilles a vin et a biere cylindriques anglaises, 1735-1850 (nO de catalogue R61-2/9-33F). En vente au Canada par l'entremise de nos agents liraires agrees et autres Iibrairies, ou par la poste au Centre d'edition du 9.0uvernement du Canada, Approvisionnements et Services Canada, Hull, Quebec, Canada KIA OS9. Price Canada: $9.50 Price outside Canada: $11.40 Price subject to change without notice. Catalogue No.: R61-2/9-33E ISBN: 0-660-12215-4 ISSN: 0821-1027 Published under the authority of the Minister of the Environment, Ottawa, 1986. Editing and design: Sheila Ascroft Cover design: Dorothy Kappler The opinions expressed in this report are those of the author and not necessarily those of Environment Canada. Parks publishes the results of its research in archaeology, architecture and history. A list of titles is available from Research Publications, Environment Canada - Parks, 1600 Liverpool Court, Ottawa, Ontario KIA IG2. CONTENTS 5 Abstract 7 Acknow ledgements 9 Introduction 11 The Dark Green Glass Tradition in England 17 How the English Glass "Wine" Bottle Was Used 27 Closures 29 Developing a Chronology for Cylindrical English "Wine" Bottles 33 Finishes and Necks 49 Catalogue of Finish Styles 73 Bodies 73 Style 84 Manufacturing Techniques 91 Heels and Bases 107 Capacity 115 Measurements 115 Capacity Estimates 115 Dating Estimates 118 Estimating Average Bottle Age from an Archaeological Assem blage 120 The Measurements 131 Conclusions --- 133 Appendix A.