Mandolin-Related Prints Until the Early 19Th Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Science of String Instruments

The Science of String Instruments Thomas D. Rossing Editor The Science of String Instruments Editor Thomas D. Rossing Stanford University Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics (CCRMA) Stanford, CA 94302-8180, USA [email protected] ISBN 978-1-4419-7109-8 e-ISBN 978-1-4419-7110-4 DOI 10.1007/978-1-4419-7110-4 Springer New York Dordrecht Heidelberg London # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2010 All rights reserved. This work may not be translated or copied in whole or in part without the written permission of the publisher (Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, 233 Spring Street, New York, NY 10013, USA), except for brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis. Use in connection with any form of information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed is forbidden. The use in this publication of trade names, trademarks, service marks, and similar terms, even if they are not identified as such, is not to be taken as an expression of opinion as to whether or not they are subject to proprietary rights. Printed on acid-free paper Springer is part of Springer ScienceþBusiness Media (www.springer.com) Contents 1 Introduction............................................................... 1 Thomas D. Rossing 2 Plucked Strings ........................................................... 11 Thomas D. Rossing 3 Guitars and Lutes ........................................................ 19 Thomas D. Rossing and Graham Caldersmith 4 Portuguese Guitar ........................................................ 47 Octavio Inacio 5 Banjo ...................................................................... 59 James Rae 6 Mandolin Family Instruments........................................... 77 David J. Cohen and Thomas D. Rossing 7 Psalteries and Zithers .................................................... 99 Andres Peekna and Thomas D. -

Ron Block Hogan's House of Music Liner Notes Smartville (Ron Block

Ron Block Hogan’s House of Music Liner Notes Smartville (Ron Block, Moonlight Canyon Publishing, BMI) Barry Bales - bass Ron Block - banjo, rhythm and lead guitar Tim Crouch - fiddle Jerry Douglas - Dobro Stuart Duncan – fiddle Clay Hess - rhythm guitar Adam Steffey – mandolin Hogan’s House of Boogie (Ron Block, Moonlight Canyon Publishing, BMI) Ron Block – banjo, rhythm and lead guitar Sam Bush - mandolin Jerry Douglas – Dobro Byron House - bass Dan Tyminski – rhythm guitar Lynn Williams – snare Wolves A-Howling (Traditional) Barry Bales - bass Ron Block - banjo Stuart Duncan - fiddle Adam Steffey - mandolin Dan Tyminski - rhythm guitar The Spotted Pony (Traditional, arr. Ron Block, Moonlight Canyon Publishing, BMI) Barry Bales - bass Ron Block - banjo, rhythm and lead guitar Stuart Duncan – fiddle Sierra Hull – octave mandolin Alison Krauss - fiddle Adam Steffey – mandolin Dan Tyminski - rhythm guitar Lynn Williams – snare Clinch Mountain Backstep (Ralph Stanley) Barry Bales - bass Ron Block - banjo, rhythm and lead guitar Stuart Duncan – fiddle Clay Hess - rhythm guitar Adam Steffey – mandolin Gentle Annie (Stephen Foster) Ron Block – banjo, guitar Tim Crouch – fiddles, cello, bowed bass Mark Fain - bass Sierra Hull – octave mandolins Mooney Flat Road (Ron Block, Moonlight Canyon Publishing, BMI) Barry Bales - bass Ron Block - banjo, rhythm and lead guitar Stuart Duncan – fiddle Sierra Hull – octave mandolin Alison Krauss - fiddle Adam Steffey – mandolin Jeff Taylor - accordion Dan Tyminski - rhythm guitar Lynn Williams – snare Mollie -

Shin Akimoto Alan Bibey Sharon Gilchrist

Class list is preliminary- subject to change Shin Akimoto Monroe Style (I) Rhythm Playing (AB) Bluegrass in Japan (All) Alan Bibey No, you backup (AB-I) Playing fills and how to play behind a vocalist Classic Bluegrass Mandolin breaks (I-A) Road to improv (I-A) Classic Monroe licks (AB-I) Spice Up your playing with triplets (I-A) Sharon Gilchrist Closed Position Fingering for Playing Melodies in All 12-Keys: (AB-I) Learn a couple of easy patterns on the fretboard that allow you to play melodies in all 12 keys easily. This is what a lot of mandolin players are using all the time and it's easy! Closed Position means using no open strings. Basic Double Stop Series: (AB-I) Double stops are one of the mandolin's signature sounds. In this class, we will learn a basic double stop series that moves up and down the neck for both major and minor chords. Freeing Up the Right Hand (B-I) This class is geared towards folks who have learned a number of fiddle tunes and have gotten pretty comfortable playing those melodies but are wondering how to speed them up a bit or breathe a little more life into them now. It is also for folks who might have been playing for a while but still struggle with speed and flow in performance of their tunes. Backing Up a Singer: (I-A) Using double stops and licks to create back up that allows the lead vocal to remain front and center while enhancing the story of the song. -

A Breath of New Life GLO 5264

A BREATH OF NEW LIFE Dutch Baroque music on original recorders from private collections Saskia Coolen - Patrick Ayrton - Rainer Zipperling GLO 5264 GLOBE RECORDS 1. Prelude in G minor (improvisation) [a] 1.37 WILLEM DE FESCH (1687-1760) Sonata No. 3 in C minor, Op. 8 [e] UNICO WILHELM 12. Ceciliana 2:00 VAN WASSENAER (1692-1766) 13. Allemanda 3:47 Sonata seconda in G minor [b] 14. Arietta. Larghetto e piano 2:16 2. Grave 2:36 15. Menuetto primo e secondo 3:08 3. Allegro 2:54 4. Adagio 1:34 PIETER BUSTIJN (1649-1729) 5. Giga presto 2:26 Suite No. 8 in A major 16. Preludio 1.43 CAROLUS HACQUART (1640-1701?) 17. Allemanda 3.33 Suite No. 10 in A minor from Chelys 18. Corrente 1.52 6. Preludium. 19. Sarabanda 2.20 Lento - Vivace - Grave 2:46 20. Giga 2.02 7. Allemande 2:26 8. Courante 1:29 From: Receuil de plusieurs pièces 9. Sarabande 2:48 de musique […] choisies par Michel 10. Gigue 1:48 de Bolhuis (1739) [f] 21. Marleburgse Marche 1.16 11. Prelude in C minor (improvisation) [d] 1.27 22. Tut, tut, tut 1.04 23. O jammer en elende 1.09 24. Savoijse kool met Ossevleis 1.28 25. Bouphon 1.18 2 JOHAN SCHENCK (1660-1712) Suite in D minor from Scherzi musicali 26. Preludium 1:36 27. Allemande 2:34 28. Courant 1:29 29. Sarabande 1:59 30. Gigue 1:45 Saskia Coolen 31. Tempo di Gavotta 1:25 recorder, viola da gamba Patrick Ayrton PHILIPPUS HACQUART (1645-1692) 1.40 harpsichord 32. -

Electric Octave Mandolin Conversion

Search Conversion of an electric mini-guitar to electric octave Where is it? mandolin by Randy Cordle Active Completed electric octave mandolin Expand All | Contract All A B C D E F G H I Shown is an electric octave mandolin that started its life as a $99 mini-guitar. Total cost J was approximately $200 with the additional cost of items used in the conversion. The K conversion process is fairly simple, and can be done with the information given here if L you have some basic woodworking skills and a few basic power tools. A drill press and 4" M tabletop belt sander were the primary tools that I used that may not be in everyone's shop, N but the project could be done using other methods. O P–Q Electric octave mandolin specifications R 22-7/8" scale S GG-DD-AA-EE unison pair tuning T Width of neck at nut is 36mm, 12th fret width is 47mm U–V Width between outer string pairs at bridge is 52mm String pair center distance is 3mm W–X Y–Z Additional parts and where they were obtained Inactive Schaller A-style mandolin tuners - $40, First Quality Musical Supplies, also Expand All | Contract All available from Stewart-McDonald .090" white pick guard material - $9, Stewart-McDonald A Switchcraft output jack (don't use the cheap existing jack) - $5, Stewart-McDonald B 1/8" bone nut blank - $4, Stewart-McDonald C Straplok strap hardware...not necessary, but they find their way on most of my stage D instruments - $13, Stewart-McDonald Testor's "make your own decals with your ink-jet printer" kit - $6, Wal-Mart E Tru-oil gunstock finish - $6, Wal-Mart -

A History of Mandolin Construction

1 - Mandolin History Chapter 1 - A History of Mandolin Construction here is a considerable amount written about the history of the mandolin, but littleT that looks at the way the instrument e marvellous has been built, rather than how it has been 16 string ullinger played, across the 300 years or so of its mandolin from 1925 existence. photo courtesy of ose interested in the classical mandolin ony ingham, ondon have tended to concentrate on the European bowlback mandolin with scant regard to the past century of American carved instruments. Similarly many American writers don’t pay great attention to anything that happened before Orville Gibson, so this introductory chapter is an attempt to give equal weight to developments on both sides of the Atlantic and to see the story of the mandolin as one of continuing evolution with the odd revolutionary change along the way. e history of the mandolin is not of a straightforward, lineal development, but one which intertwines with the stories of guitars, lutes and other stringed instruments over the past 1000 years. e formal, musicological definition of a (usually called the Neapolitan mandolin); mandolin is that of a chordophone of the instruments with a flat soundboard and short-necked lute family with four double back (sometimes known as a Portuguese courses of metal strings tuned g’-d’-a”-e”. style); and those with a carved soundboard ese are fixed to the end of the body using and back as developed by the Gibson a floating bridge and with a string length of company a century ago. -

Course Outline: Guitar & Mandolin Orchestra

Course Outline: Guitar & Mandolin Orchestra Guitar & Mandolin Orchestra (G&MO) is a large ensemble that performs music on acoustic guitars, bass guitars, mandolins, mandolas and mandocellos. Activities involving performance techniques, general musicianship and creative/critical thinking are emphasized during rehearsals. Membership satisfies the participation requirement for regional and all-state honors ensembles. Course prerequisites: because the ensemble is focused on performing music in a selective and balanced setting, all students must audition. NOTE: students who have successfully auditioned for BCA Orchestra on the following instruments may register without an audition: violin, viola, cello, bass. Course Goals and Objectives Ultimately, students in Guitar & Mandolin Orchestra present several performances throughout the academic year. Importantly, members explore various styles of music including: classical, jazz, international, and folk music. Through exploration, students will experience several techniques and interpretive practices necessary to perform these styles. Creative strategies are utilized in order to expose students to a variety of related musical concepts including history, foreign language, improvisation, critique, conducting, and music theory. Grading, Assessment and Course Responsibilities Grades are based on the average of all class sessions, dress rehearsals, and performances. Points are awarded based on assessment for preparation, participation, attendance and team work- because they foster responsible adult practices. A = 93 -100 A- = 90 – 92 B+ = 87 - 89 B = 83 - 86 B- = 80 - 82 C+ = 77 - 79 C = 73 - 76 C- = 70 - 72 D+ = 63 - 69 D = 60 - 62 F = 0 - 59 Preparation (approx. 70%): Students who are present and prepared earn 3 points each class session as follows: 2 points for bringing instrument and individual copy of sheet music, 1 point for preparing any assigned material and/or participating in class activities. -

DAKOTA OCTAVE MANDOLIN KIT and MANDOCELLO KIT

DAKOTA OCTAVE MANDOLIN KIT and MANDOCELLO KIT MUSICMAKER’S KITS, INC PO Box 2117 Stillwater, MN 55082 651-439-9120 harpkit.comcom WOOD PARTS: DAKOTA OCTAVE MANDOLIN KIT A - Neck B - Fretboard C - Heel Block Z R D - Tail Block E - 2 Heel Ribs F - 2 Side Ribs G - 2 Tail Ribs A P H - 4 Corner Blocks I B I - Back Panel J - 3 Cross-Braces for Back K - 2 Flat Braces for Back L L - Front (Soundboard) N M - 10 Braces for Front (Soundboard) O N - 6 Inner Kerfing Strips O - Bridge (with Saddle & 8 pegs) X V P - Bridge Clamp, w/4 machine screws, 2 washers, 2 wing nuts U Q - Bridge Plate E T R - 4 Clamping Wedges C E S - Spacer Block T - 6 Binding Strips, walnut HH U - Heel Cap Y V - Truss Rod Cover (with 3 screws) F F HARDWARE: S K J M W - 48 Inches Fretwire X - 1 White Side Marker Rod 5/64”” X 2” Y - 8 Black Geared Tuners H H w/8 sleeves, 8 washers & 8 tiny screws Z - Double Truss Rod, with allen wrench 8 - Pearl Marking Dots, 1/4” dia. Q 1 - Heavy Fretwire, 2” long, for #0 fret G G 1 - Set of 8 Strings D 1 - Black Wood Nut Fig 1 W 1 - Hex Bolt, 1/4” X 2”, with washer 2 - Tiny Nails If you have any questions about the assembly of your 1 - Drill Bit, 1/16” for tiny screws 1 - Drill Bit, 5/64” for Side Markers kit - please visit our online Builder’s Forum 1 - Drill Bit, 3/16” for bridge www.harpkit.com/forum Assembly Instructions A NOTE ABOUT GLUE We recommend assembling this kit with standard woodworker’s glue (such as Elmer’s Carpenters Glue or Titebond Wood Glue). -

English Lute Manuscripts and Scribes 1530-1630

ENGLISH LUTE MANUSCRIPTS AND SCRIBES 1530-1630 An examination of the place of the lute in 16th- and 17th-century English Society through a study of the English Lute Manuscripts of the so-called 'Golden Age', including a comprehensive catalogue of the sources. JULIA CRAIG-MCFEELY Oxford, 2000 A major part of this book was originally submitted to the University of Oxford in 1993 as a Doctoral thesis ENGLISH LUTE MANUSCRIPTS AND SCRIBES 1530-1630 All text reproduced under this title is © 2000 JULIA CRAIG-McFEELY The following chapters are available as downloadable pdf files. Click in the link boxes to access the files. README......................................................................................................................i EDITORIAL POLICY.......................................................................................................iii ABBREVIATIONS: ........................................................................................................iv General...................................................................................iv Library sigla.............................................................................v Manuscripts ............................................................................vi Sixteenth- and seventeenth-century printed sources............................ix GLOSSARY OF TERMS: ................................................................................................XII Palaeographical: letters..............................................................xii -

The Musicians of Ma'alwyck

Musicians of Ma’alwyck Presents Beethoven 250th Anniversary Celebration Concert Sunday, November 1, 2020 @ 3pm Schuyler Mansion State Historic Site Dear Friend, Thank you for joining us virtually today. We are sorry we cannot be enjoying this program together here in the music salon of the Schuyler Mansion, but we are pleased that we can still celebrate Beethoven’s landmark year together even if it is just on line. The program we have prepared for you features both the well-known and charming Serenade op 25, which we have transcribed to include guitar instead of viola, the early duo Woo 26 and then a wonderful Potpourri of Beethoven’s Favorite Melodies by Anton Diabelli. Each work displays a different side of Beethoven, whether a young still forming genius or the lighter occasional music side. The acoustic in the Schuyler Mansion allows for nuanced playing and recreates a setting for Beethoven’s that is historically quite accurate. We will continue throughout the duration of COVID restrictions to offer creative programming. Much of the virtual work we are doing is available on the Musicians of Ma’alwyck Youtube channel. I also write a weekly Musical Treasure Chest about pieces important to me that is available on our website, and the ensemble in various configurations performs every Sunday at 3pm on the First Reformed Church of Schenectady’s Youtube channel. Each month we are releasing a “short” video collaborating with historic sites and other artistic media. Our first “short” was filmed in October in the Crypt at Hyde Hall near Cooperstown, New York. -

Johann Helmich Roman GOLOVINMUSIKEN Höör Barock & Dan Laurin

Unknown artist: Utsikt från Slottsbacken, vinterbild (‘View from the Castle Slope, Stockholm’). Oil on canvas, 81.5 x 146.5 cm, beginning of the 18th century. The painting must have been made shortly after 1697 when the old Royal Palace was destroyed in a fire – the artist has included the ruins (below). Across the water is the so-called Bååtska Palatset, where the Golovin Music was performed for the first time in 1728. Johann Helmich Roman GOLOVINMUSIKEN Höör Barock & Dan Laurin BIS-2355 Johan Helmich Roman (1694–1758) Golovinmusiken – The Golovin Music Musique satt til en Festin hos Ryska Ministren Gref Gollowin (Music for a banquet held by the Russian envoy Count Golovin) Höör Barock Dan Laurin recorders and direction Performing version by Dan Laurin, based on the composer’s autograph and the score by Ingmar Bengtsson and Lars Frydén published by Edition Reimers. In Roman’s autograph manuscript each movement has a number, but there are no other headings in the form of titles or tempo markings. Those provided here, in square brack- ets, are the performers’ suggestions for how the different pieces may be interpreted in terms of genre or character. first complete recording TT: 81'53 2 1 [Allegro] Violin 1, violin 2, viola, cello, double bass, mandora, harpsichord 2'09 2 [Ouverture] Sixth flute**, oboe, oboe d’amore, bassoon, violin 1, violin 2, 1'51 viola, cello, double bass, mandora, harpsichord 3 [Larghetto] Tenor recorder, voice flute***, bass recorder**, violin 2, 3'06 viola, cello, double bass, mandora 4 [Allegro assai] Violin 1, violin -

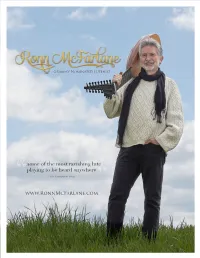

…Some of the Most Ravishing Lute Playing to Be Heard Anywhere

Grammy-Nominated Lutenist …some of the most ravishing lute playing to be heard anywhere “ ~The Washington Times ” www.RonnMcFarlane.com probably the fnest living exponent of his instrument AbeguilingrecordingbytheUSlutenistwhich ~The Times Colonist, Victoria, B.C. beautifully balances traditional Scottish and Irish tunes with works by Turlough O’Carolan “ ~BBC Music Magazine “ ” GRAMMY-nominated lutenist, Ronn McFarlane brings the lute - the most popular instrument of the ” Renaissance - into today’s musical mainstream making it accessible to a wider audience. Since taking up the lute in 1978, Ronn has made his mark in music as the founder of Ayreheart, a founding member of the Baltimore Consort, touring 49 of the 50 United States, Canada, England, Scotland, Netherlands, Germany and Austria, and as a guest artist with Apollo’s Fire, The Bach Sinfonia, The Catacoustic Consort, The Folger Consort, Houston Grand Opera, The Oregon Symphony, The Portland Baroque Orchestra, and The Indianapolis Baroque Orchestra. Born in West Virginia, Ronn grew up in Maryland. At thirteen, upon hearing “Wipeout” by the Surfaris, he fell madly in love with music and The Celtic Lute taught himself to play on a “cranky sixteen-dollar steel string guitar.” Released in 2018, Ronn's newest solo Ronn kept at it, playing blues and rock music on the electric guitar while album features all-new arrangements of traditional Irish and Scottish folk music studying classical guitar. He graduated with honors from Shenandoah Conservatory and continued guitar studies at Peabody Conservatory before turning his full attention and energy to the lute in 1978. McFarlane was a faculty member of the Peabody Conservatory from Solo Discography 1984 to 1995, teaching lute and lute-related subjects.