Submission to The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Accelerated Reader Quiz List

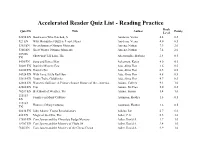

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Book Quiz ID Title Author Points Level 32294 EN Bookworm Who Hatched, A Aardema, Verna 4.4 0.5 923 EN Why Mosquitoes Buzz in People's Ears Aardema, Verna 4.0 0.5 5365 EN Great Summer Olympic Moments Aaseng, Nathan 7.9 2.0 5366 EN Great Winter Olympic Moments Aaseng, Nathan 7.4 2.0 107286 Show-and-Tell Lion, The Abercrombie, Barbara 2.4 0.5 EN 5490 EN Song and Dance Man Ackerman, Karen 4.0 0.5 50081 EN Daniel's Mystery Egg Ada, Alma Flor 1.6 0.5 64100 EN Daniel's Pet Ada, Alma Flor 0.5 0.5 54924 EN With Love, Little Red Hen Ada, Alma Flor 4.8 0.5 35610 EN Yours Truly, Goldilocks Ada, Alma Flor 4.7 0.5 62668 EN Women's Suffrage: A Primary Source History of the...America Adams, Colleen 9.1 1.0 42680 EN Tipi Adams, McCrea 5.0 0.5 70287 EN Best Book of Weather, The Adams, Simon 5.4 1.0 115183 Families in Many Cultures Adamson, Heather 1.6 0.5 EN 115184 Homes in Many Cultures Adamson, Heather 1.6 0.5 EN 60434 EN John Adams: Young Revolutionary Adkins, Jan 6.7 6.0 480 EN Magic of the Glits, The Adler, C.S. 5.5 3.0 17659 EN Cam Jansen and the Chocolate Fudge Mystery Adler, David A. 3.7 1.0 18707 EN Cam Jansen and the Mystery of Flight 54 Adler, David A. 3.4 1.0 7605 EN Cam Jansen and the Mystery of the Circus Clown Adler, David A. -

EBCS AR Titles

EBCS AR Titles QUIZNO TITLE 41025EN The 100th Day of School 35821EN 100th Day Worries 661EN The 18th EmerGency 7351EN 20,000 Baseball Cards Under the Sea 11592EN 2095 8001EN 50 Below Zero 9001EN The 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins 413EN The 89th Kitten 80599EN A-10 Thunderbolt II 16201EN A...B...Sea (Crabapples) 67750EN Abe Lincoln Goes to WashinGton 1837-1865 101EN Abel's Island 9751EN Abiyoyo 86635EN The Abominable Snowman Doesn't Roast Marshmallows 13551EN Abraham Lincoln 866EN Abraham Lincoln 118278EN Abraham Lincoln and the Civil War 17651EN The Absent Author 21662EN The Absent-Minded Toad 12573EN The Absolutely True Story...How I Visited Yellowstone... 17501EN Abuela 15175EN Abyssinian Cats (Checkerboard) 6001EN Ace: The Very Important PiG 35608EN The Acrobat and the AnGel 105906EN Across the Blue Pacific: A World War II Story 7201EN Across the Stream 1EN Adam of the Road 301EN Addie Across the Prairie 6101EN Addie Meets Max 13851EN Adios, Anna 135470EN Adrian Peterson 128373EN Adventure AccordinG to Humphrey 451EN The Adventures of Ali Baba Bernstein 20251EN The Adventures of Captain Underpants 138969EN The Adventures of Nanny PiGGins 401EN The Adventures of Ratman 64111EN The Adventures of Super Diaper Baby 71944EN AfGhanistan (Countries in the News) 71813EN Africa 70797EN Africa (The Atlas of the Seven Continents) 13552EN African-American Holidays EBCS AR Titles 13001EN African Buffalo (African Animals Discovery) 15401EN African Elephants (Early Bird Nature) 14651EN Afternoon on the Amazon 83309EN Air: A Resource Our World Depends -

TAZ, Ontological Anarchy, Poetic Terrorism.Pdf

T. A. Z. The Temporary Autonomous Zone, Ontological Anarchy, Poetic Terrorism By Hakim Bey Autonomedia Anti-copyright, 1985, 1991. May be freely pirated & quoted-- the author & publisher, however, would like to be informed at: Autonomedia P. O. Box 568 Williamsburgh Station Brooklyn, NY 11211-0568 Book design & typesetting: Dave Mandl HTML version: Mike Morrison Printed in the United States of America Part 1 T. A. Z. The Temporary Autonomous Zone, Ontological Anarchy, Poetic Terrorism By Hakim Bey ACKNOWLEDGMENTS CHAOS: THE BROADSHEETS OF ONTOLOGICAL ANARCHISM was first published in 1985 by Grim Reaper Press of Weehawken, New Jersey; a later re-issue was published in Providence, Rhode Island, and this edition was pirated in Boulder, Colorado. Another edition was released by Verlag Golem of Providence in 1990, and pirated in Santa Cruz, California, by We Press. "The Temporary Autonomous Zone" was performed at the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics in Boulder, and on WBAI-FM in New York City, in 1990. Thanx to the following publications, current and defunct, in which some of these pieces appeared (no doubt I've lost or forgotten many--sorry!): KAOS (London); Ganymede (London); Pan (Amsterdam); Popular Reality; Exquisite Corpse (also Stiffest of the Corpse, City Lights); Anarchy (Columbia, MO); Factsheet Five; Dharma Combat; OVO; City Lights Review; Rants and Incendiary Tracts (Amok); Apocalypse Culture (Amok); Mondo 2000; The Sporadical; Black Eye; Moorish Science Monitor; FEH!; Fag Rag; The Storm!; Panic (Chicago); Bolo Log (Zurich); Anathema; Seditious Delicious; Minor Problems (London); AQUA; Prakilpana. Also, thanx to the following individuals: Jim Fleming; James Koehnline; Sue Ann Harkey; Sharon Gannon; Dave Mandl; Bob Black; Robert Anton Wilson; William Burroughs; "P.M."; Joel Birroco; Adam Parfrey; Brett Rutherford; Jake Rabinowitz; Allen Ginsberg; Anne Waldman; Frank Torey; Andr Codrescu; Dave Crowbar; Ivan Stang; Nathaniel Tarn; Chris Funkhauser; Steve Englander; Alex Trotter. -

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Quiz Book Title Author Points No

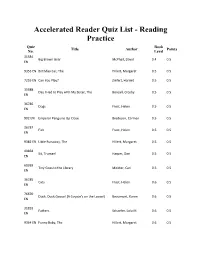

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Quiz Book Title Author Points No. Level 31584 Big Brown Bear McPhail, David 0.4 0.5 EN 9353 EN Birthday Car, The Hillert, Margaret 0.5 0.5 7255 EN Can You Play? Ziefert, Harriet 0.5 0.5 35988 Day I Had to Play with My Sister, The Bonsall, Crosby 0.5 0.5 EN 36786 Dogs Frost, Helen 0.5 0.5 EN 902 EN Emperor Penguins Up Close Bredeson, Carmen 0.5 0.5 36787 Fish Frost, Helen 0.5 0.5 EN 9382 EN Little Runaway, The Hillert, Margaret 0.5 0.5 49858 Sit, Truman! Harper, Dan 0.5 0.5 EN 60939 Tiny Goes to the Library Meister, Cari 0.5 0.5 EN 36785 Cats Frost, Helen 0.6 0.5 EN 76670 Duck, Duck,Goose! (A Coyote's on the Loose!) Beaumont, Karen 0.6 0.5 EN 31833 Fathers Schaefer, Lola M. 0.6 0.5 EN 9364 EN Funny Baby, The Hillert, Margaret 0.6 0.5 9383 EN Magic Beans, The Hillert, Margaret 0.6 0.5 83514 Puppy Mudge Finds a Friend Rylant, Cynthia 0.6 0.5 EN 88312 Puppy Mudge Wants to Play Rylant, Cynthia 0.6 0.5 EN 59439 Rosie's Walk Hutchins, Pat 0.6 0.5 EN 9391 EN Three Bears, The Hillert, Margaret 0.6 0.5 9392 EN Three Goats, The Hillert, Margaret 0.6 0.5 9393 EN Three Little Pigs, The Hillert, Margaret 0.6 0.5 9400 EN Yellow Boat, The Hillert, Margaret 0.6 0.5 9355 EN Cinderella at the Ball Hillert, Margaret 0.7 0.5 31818 Family Pets Schaefer, Lola M. -

MELBOURNE PROGRAM GUIDE Sunday 10Th January 2016

MELBOURNE PROGRAM GUIDE Sunday 10th January 2016 06:00 am Toasted TV G Want the lowdown on what's hot in the playground? Join the team for the latest in pranks, pop culture, movies, music, sport, games and other seriously fun stuff! Featuring a variety of your favourite cartoons. 06:05 am Matt Hatter Chronicles G The Chaos Coin Matt has moved to live above his Grandpa's movie theatre, but this theatre is more than just a cool old building; it is a gateway to another reality known as "The Multiverse". 06:30 am Invizimals (Rpt) G The Alliance Part 1 Keni is a young, supergifted scientific researcher that discovers the Invizimals during a routine experiment. Keni begins to collaborate with the Invizimals to develope completely new and pioneering technology. 07:00 am Toasted TV G Want the lowdown on what's hot in the playground? Join the team for the latest in pranks, pop culture, movies, music, sport, games and other seriously fun stuff! Featuring a variety of your favourite cartoons. 07:05 am Beyblade: Shogun Steel (Rpt) G The Ultimate Emperor Of Destruction: Bahamoote Seven years have passed since the god of Destruction, Nemesis met his end at the hands of a Legendary Blader. A new era of Beyblade has begun, bringing with it new Blades. 07:30 am Toasted TV G Want the lowdown on what's hot in the playground? Join the team for the latest in pranks, pop culture, movies, music, sport, games and other seriously fun stuff! Featuring a variety of your favourite cartoons. -

No. 269 October 10

small screen News Digest of Australian Council on Children and the Media (incorporating Young Media Australia) ISSN: 0817-8224 No. 269 October 2010 Changes at ACCM The Australian Children’s Television Children lie to join Facebook Foundation (ACTF), the founding Present- Professor Elizabeth ing Partner of Trop Jr, is again providing Handsley was elect- According to Jim O’Rourke, writing in The support to the festival. ABC3, ABC TV’s ed President of the Age, children as young as 8 are signing up dedicated children’s digital channel, is the Australian Council to Facebook and exposing themselves to Major Media Partner. on Children and the cyber bullying and online predators. media at the Annual Entries close on 6 January and young film- General Meeting held Both police and teachers are warning makers can enter online. To be eligible, they on Tuesday 26 October parents to be more vigilant when it comes to will have to create a film that is no longer 2010. their children and Facebook. They say that than seven minutes long that must feature a growing number of children are flouting the Trop Jr Signature Item for 2011 – FAN Jane Roberts (WA) is the new Vice- the Facebook age restrictions and creating - to prove it was made for the festival President. We are happy to welcome new accounts despite the age requirement. Directors, Kym Goodes (Tasmania) and These children have to lie about their age http://www.tropjr.com.au Marjorie Voss (Queensland) . because users have to be over 13 to create a Facebook account and many parents are Rev Elisabeth Crossman (Qld), Anne Fit- unaware that this is happening. -

EUREKA Country Mile! Garages & Sheds Farming and Industrial Structures

The Moorabool News FREE Your Local News Tuesday 5 November, 2013 Serving Ballan and district since 1872 Phone 5368 1966 Fax 5368 2764 Vol 7 No 43 He’s our man! By Kate Taylor Central Ward Councillor Paul Tatchell has been voted as Moorabool’s new Mayor. East Ward Councillor John Spain was voted in as Deputy Mayor. Outgoing Mayor Pat Toohey did not re-nominate at the Statutory and Annual Appointments Meeting held last Wednesday 30 October, where Mayor Tatchell won the role with a 5-2 majority. Nominated by East Ward Councillor Allan Comrie, Cr Tatchell gained votes from fellow councillors Comrie, David Edwards, Tonia Dudzik and John Spain. West Ward Councillor Tom Sullivan was nominated and voted for by Pat Toohey. New Mayor Tatchell told the meeting he was very fortunate to have been given the privilege of the role. “For former mayor Pat Toohey, to have come on board and then taken on the role of Mayor with four new councillors, he jumped straight in the driver’s seat… and the first few months were very difficult, but he persevered with extreme patience. “And to the experienced councillors we came in contact with from day one, with years of experience, without that, I can’t imagine how a council could have operated with seven new faces. We are incredibly fortunate to have those experienced councillors on board.” Mayor Tatchell also hinted at a vision for more unity in the future. “A bit less of ‘I’ and more of ‘we,’” he said. Deputy Mayor Spain was voted in with votes from councillors Dudzik, Edwards, and Comrie, with Mayor Tatchell not required to cast a vote on a majority decision. -

From Squatting to Tactical Media Art in the Netherlands, 1979–1993

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 5-2019 Between the Cracks: From Squatting to Tactical Media Art in the Netherlands, 1979–1993 Amanda S. Wasielewski The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/3125 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] BETWEEN THE CRACKS: FROM SQUATTING TO TACTICAL MEDIA ART IN THE NETHERLANDS, 1979–1993 by AMANDA WASIELEWSKI A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Art History in partiaL fulfiLLment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of PhiLosophy, The City University of New York 2019 © 2019 AMANDA WASIELEWSKI ALL Rights Reserved ii Between the Cracks: From Squatting to TacticaL Media Art in the Netherlands, 1979–1993 by Amanda WasieLewski This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Art History in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of PhiLosophy. Date David JoseLit Chair of Examining Committee Date RacheL Kousser Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Marta Gutman Lev Manovich Marga van MecheLen THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Between the Cracks: From Squatting to TacticaL Media Art in the Netherlands, 1979–1993 by Amanda WasieLewski Advisor: David JoseLit In the early 1980s, Amsterdam was a battLeground. During this time, conflicts between squatters, property owners, and the police frequentLy escaLated into fulL-scaLe riots. -

Worst Fears Realised

48 STAYING IN SUNDAY DECEMBER 7 2014 QUIZ Neighbours 5D 4A, 3B, 2D, 1C, Answers: 1. In March 2. Which singer and 3. The show is set 4. And what is the 5. Which actor next year, what past cast member is in a fictional suburb name of the show’s is noted as the anniversary will set to return for the of which Australian fictional suburb? longest-serving Neighbours be celebrations? city? A. Erinsborough cast member? celebrating? A. Natalie Imbruglia A. Sydney B. Erinsburgh A. Jackie Woodburne A. 20 years B. Kylie Minogue B. Melbourne C. Ramsaville (pictured) TV today B. 25 years C. Jason Donovan C. Brisbane D. Ramsay B. Anne Haddy C. 30 years D. Delta Goodrem D. Perth C. Ian Smith Sunday, December 7, 2014 D. 35 years D. Tom Oliver imparja 6.00 Weekend Today. Worst fears realised 8.30 The Wildlife he loss of a child is one of the It’s a happy, idyllic time for the fam- The Irish actor says The Missing not Man Featuring David Ireland. most profound, primal fears a par- ily, one that quickly turns nightmarish only explores the investigation into Oli- 9.30 Endangered. T ent could ever experience. when Tony loses sight of Oliver in a busy ver’s disappearance but also delves into 10.30 MOVIE: Big But combine it with a lingering feeling crowd. The boy vanishes without trace. the personalities of everyone involved in Wednesday. (1978) of uncertainty over the child’s fate and An investigation fails to find Oliver or the case, especially Tony and Emily. -

Today's Television

36 TV SATURDAY SEPTEMBER 20 2014 Zits Insanity Streak Snake Tales Swamp 200914 Start the day Today’s TeleVision with a laugh nine scTV darwin abc sbs one Ten digiTal 6.00 Guppies. (R, CC) 6.30 Dora. 6.00 Saturday Disney. (CC) 6.00 Rage. (PG, CC) 11.30 6.00 WorldWatch. 7.00 Hindi 6.00 Ready Steady Cook. (R, CC) A RETIRED man is (R, CC) 7.00 Weekend Today. 7.00 Weekend Sunrise. (CC) Catalyst. (PG, R, CC) 12.00 News. 7.25 Italian News. 8.05 7.00 GCBC. (R, CC) 8.00 Everyday organising his will and (CC) 10.00 Mornings: Saturday. 10.00 The Morning Show: Australian Story. (R, CC) 12.30 Filipino News. 8.40 French News. Gourmet. (R, CC) 8.30 St10. (CC) (PG, CC) 12.00 The Middle. (PG, Weekend. (PG, CC) The Restaurant Inspector. (PG, 9.30 Greek News. 10.30 German 10.00 St10: Extra. (PG, CC) 11.00 consulting with his R, CC) 12.30 Hot In Cleveland. 12.00 Dr Oz. (PG, CC) CC) (Series return) 1.30 QI. (PG, News. 11.00 Spanish News. 12.00 Jamie’s Great Britain. (PG, R, CC) solicitor. He tells the (PG, R, CC) 1.00 Super Fun Night. 1.00 MOVIE: The Proud R, CC) 2.00 Inspector George Arabic News. 12.30 Turkish News. (Final) 12.00 The Living Room. (PG, R, CC) 1.30 MOVIE: Little Family Movie. (R, Gently. (PG, R, CC) 1.00 Swan Lake: Mariinsky Ballet. (PG, R, CC) 1.00 The Talk. -

Convergence 2011: Australian Content State of Play

Screen Australia AUSTRALIAN CONTENT STATE OF PLAY informing debate AUGUST 2011 CONVERGENCE 2011: AUSTRALIAN CONTENT STATE OF PLAY © Screen Australia 2011 ISBN 978-1-920998-15-8 This report draws from a number of sources. Screen Australia has undertaken all reasonable measures to ensure its accuracy and therefore cannot accept responsibility for inaccuracies and omissions. First released 25 August 2011; this edition 26 August 2011 www.screenaustralia.gov.au/research Screen Australia – August 2011 2 CONVERGENCE 2011: AUSTRALIAN CONTENT STATE OF PLAY CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Executive summary ............................................................................................................ 5 1.2 Mapping the media environment ................................................................................ 11 2 CREATING AUSTRALIAN CONTENT ................................................................... 20 2.1 The economics of screen content production ...................................................... 20 2.2 How Australian narrative content gets made ....................................................... 27 2.3 Value to the economy of narrative content production .................................... 39 3 DELIVERING AUSTRALIAN CONTENT .............................................................. 41 3.1 Commercial free-to-air television ............................................................................. -

T. A. Z. the Temporary Autonomous Zone, Ontological Anarchy, Poetic Terrorism

T. A. Z. The Temporary Autonomous Zone, Ontological Anarchy, Poetic Terrorism By Hakim Bey Autonomedia Anti-copyright, 1985, 1991. May be freely pirated & quoted-- the author & publisher, however, would like to be informed at: Autonomedia P. O. Box 568 Williamsburgh Station Brooklyn, NY 11211-0568 Book design & typesetting: Dave Mandl HTML version: Mike Morrison Printed in the United States of America ACKNOWLEDGMENTS CHAOS: THE BROADSHEETS OF ONTOLOGICAL ANARCHISM was first published in 1985 by Grim Reaper Press of Weehawken, New Jersey; a later re-issue was published in Providence, Rhode Island, and this edition was pirated in Boulder, Colorado. Another edition was released by Verlag Golem of Providence in 1990, and pirated in Santa Cruz, California, by We Press. "The Temporary Autonomous Zone" was performed at the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics in Boulder, and on WBAI-FM in New York City, in 1990. Thanx to the following publications, current and defunct, in which some of these pieces appeared (no doubt I've lost or forgotten many-- sorry!): KAOS (London); Ganymede (London); Pan (Amsterdam); Popular Reality; Exquisite Corpse (also Stiffest of the Corpse, City Lights); Anarchy (Columbia, MO); Factsheet Five; Dharma Combat; OVO; City Lights Review; Rants and Incendiary Tracts (Amok);Apocalypse Culture (Amok); Mondo 2000; The Sporadical; Black Eye; Moorish Science Monitor; FEH!; Fag Rag; The Storm!; Panic(Chicago); Bolo Log (Zurich); Anathema; Seditious Delicious; Minor Problems (London); AQUA; Prakilpana. Also, thanx to the following individuals: Jim Fleming; James Koehnline; Sue Ann Harkey; Sharon Gannon; Dave Mandl; Bob Black; Robert Anton Wilson; William Burroughs; "P.M."; Joel Birroco; Adam Parfrey; Brett Rutherford; Jake Rabinowitz; Allen Ginsberg; Anne Waldman; Frank Torey; Andr Codrescu; Dave Crowbar; Ivan Stang; Nathaniel Tarn; Chris Funkhauser; Steve Englander; Alex Trotter.