05-10-2019 Rigoletto Eve.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parsifal and Canada: a Documentary Study

Parsifal and Canada: A Documentary Study The Canadian Opera Company is preparing to stage Parsifal in Toronto for the first time in 115 years; seven performances are planned for the Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts from September 25 to October 18, 2020. Restrictions on public gatherings imposed as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic have placed the production in jeopardy. Wagnerians have so far suffered the cancellation of the COC’s Flying Dutchman, Chicago Lyric Opera’s Ring cycle and the entire Bayreuth Festival for 2020. It will be a hard blow if the COC Parsifal follows in the footsteps of a projected performance of Parsifal in Montreal over 100 years ago. Quinlan Opera Company from England, which mounted a series of 20 operas in Montreal in the spring of 1914 (including a complete Ring cycle), announced plans to return in the fall of 1914 for another feast of opera, including Parsifal. But World War One intervened, the Parsifal production was cancelled, and the Quinlan company went out of business. Let us hope that history does not repeat itself.1 While we await news of whether the COC production will be mounted, it is an opportune time to reflect on Parsifal and its various resonances in Canadian music history. This article will consider three aspects of Parsifal and Canada: 1) a performance history, including both excerpts and complete presentations; 2) remarks on some Canadian singers who have sung Parsifal roles; and 3) Canadian scholarship on Parsifal. NB: The indication [DS] refers the reader to sources that are reproduced in the documentation portfolio that accompanies this article. -

01-25-2020 Boheme Eve.Indd

GIACOMO PUCCINI la bohème conductor Opera in four acts Marco Armiliato Libretto by Giuseppe Giacosa and production Franco Zeffirelli Luigi Illica, based on the novel Scènes de la Vie de Bohème by Henri Murger set designer Franco Zeffirelli Saturday, January 25, 2020 costume designer 8:00–11:05 PM Peter J. Hall lighting designer Gil Wechsler revival stage director Gregory Keller The production of La Bohème was made possible by a generous gift from Mrs. Donald D. Harrington Revival a gift of Rolex general manager Peter Gelb This season’s performances of La Bohème jeanette lerman-neubauer and Turandot are dedicated to the memory music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin of Franco Zeffirelli. 2019–20 SEASON The 1,344th Metropolitan Opera performance of GIACOMO PUCCINI’S la bohème conductor Marco Armiliato in order of vocal appearance marcello muset ta Artur Ruciński Susanna Phillips rodolfo a customhouse serge ant Roberto Alagna Joseph Turi colline a customhouse officer Christian Van Horn Edward Hanlon schaunard Elliot Madore* benoit Donald Maxwell mimì Maria Agresta Tonight’s performances of parpignol the roles of Mimì Gregory Warren and Rodolfo are underwritten by the alcindoro Jan Shrem and Donald Maxwell Maria Manetti Shrem Great Singers Fund. Saturday, January 25, 2020, 8:00–11:05PM MARTY SOHL / MET OPERA Roberto Alagna as Chorus Master Donald Palumbo Rodolfo and Maria Musical Preparation Caren Levine*, Joshua Greene, Agresta as Mimì in Jonathan C. Kelly, and Patrick Furrer Puccini’s La Bohème Assistant Stage Directors Mirabelle Ordinaire and J. Knighten Smit Met Titles Sonya Friedman Stage Band Conductor Joseph Lawson Children’s Chorus Director Anthony Piccolo Italian Coach Loretta Di Franco Prompter Joshua Greene Associate Designer David Reppa Scenery, properties, and electrical props constructed and painted in Metropolitan Opera Shops Costumes executed by Metropolitan Opera Costume Department Wigs and Makeup executed by Metropolitan Opera Wig and Makeup Department Ladies millinery by Reggie G. -

10-26-2019 Manon Mat.Indd

JULES MASSENET manon conductor Opera in five acts Maurizio Benini Libretto by Henri Meilhac and Philippe production Laurent Pelly Gille, based on the novel L’Histoire du Chevalier des Grieux et de Manon Lescaut set designer Chantal Thomas by Abbé Antoine-François Prévost costume designer Saturday, October 26, 2019 Laurent Pelly 1:00–5:05PM lighting designer Joël Adam Last time this season choreographer Lionel Hoche revival stage director The production of Manon was Christian Räth made possible by a generous gift from The Sybil B. Harrington Endowment Fund general manager Peter Gelb Manon is a co-production of the Metropolitan Opera; jeanette lerman-neubauer Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London; Teatro music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin alla Scala, Milan; and Théâtre du Capitole de Toulouse 2019–20 SEASON The 279th Metropolitan Opera performance of JULES MASSENET’S manon conductor Maurizio Benini in order of vocal appearance guillot de morfontaine manon lescaut Carlo Bosi Lisette Oropesa* de brétigny chevalier des grieux Brett Polegato Michael Fabiano pousset te a maid Jacqueline Echols Edyta Kulczak javot te comte des grieux Laura Krumm Kwangchul Youn roset te Maya Lahyani an innkeeper Paul Corona lescaut Artur Ruciński guards Mario Bahg** Jeongcheol Cha Saturday, October 26, 2019, 1:00–5:05PM This afternoon’s performance is being transmitted live in high definition to movie theaters worldwide. The Met: Live in HD series is made possible by a generous grant from its founding sponsor, The Neubauer Family Foundation. Digital support of The Met: Live in HD is provided by Bloomberg Philanthropies. The Met: Live in HD series is supported by Rolex. -

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details Listen at WQXR.ORG/OPERAVORE Monday, October, 7, 2013 Rigoletto Duke - Luciano Pavarotti, tenor Rigoletto - Leo Nucci, baritone Gilda - June Anderson, soprano Sparafucile - Nicolai Ghiaurov, bass Maddalena – Shirley Verrett, mezzo Giovanna – Vitalba Mosca, mezzo Count of Ceprano – Natale de Carolis, baritone Count of Ceprano – Carlo de Bortoli, bass The Contessa – Anna Caterina Antonacci, mezzo Marullo – Roberto Scaltriti, baritone Borsa – Piero de Palma, tenor Usher - Orazio Mori, bass Page of the duchess – Marilena Laurenza, mezzo Bologna Community Theater Orchestra Bologna Community Theater Chorus Riccardo Chailly, conductor London 425846 Nabucco Nabucco – Tito Gobbi, baritone Ismaele – Bruno Prevedi, tenor Zaccaria – Carlo Cava, bass Abigaille – Elena Souliotis, soprano Fenena – Dora Carral, mezzo Gran Sacerdote – Giovanni Foiani, baritone Abdallo – Walter Krautler, tenor Anna – Anna d’Auria, soprano Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra Vienna State Opera Chorus Lamberto Gardelli, conductor London 001615302 Aida Aida – Leontyne Price, soprano Amneris – Grace Bumbry, mezzo Radames – Placido Domingo, tenor Amonasro – Sherrill Milnes, baritone Ramfis – Ruggero Raimondi, bass-baritone The King of Egypt – Hans Sotin, bass Messenger – Bruce Brewer, tenor High Priestess – Joyce Mathis, soprano London Symphony Orchestra The John Alldis Choir Erich Leinsdorf, conductor RCA Victor Red Seal 39498 Simon Boccanegra Simon Boccanegra – Piero Cappuccilli, baritone Jacopo Fiesco - Paul Plishka, bass Paolo Albiani – Carlos Chausson, bass-baritone Pietro – Alfonso Echevarria, bass Amelia – Anna Tomowa-Sintow, soprano Gabriele Adorno – Jaume Aragall, tenor The Maid – Maria Angels Sarroca, soprano Captain of the Crossbowmen – Antonio Comas Symphony Orchestra of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Chorus of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Uwe Mund, conductor Recorded live on May 31, 1990 Falstaff Sir John Falstaff – Bryn Terfel, baritone Pistola – Anatoli Kotscherga, bass Bardolfo – Anthony Mee, tenor Dr. -

Lafeniceinpiazza Don Carlo Di Giuseppe Verdi Inaugura Domenica

! COMUNICATO STAMPA Venezia, 23 ottobre 2019 LaFeniceinPiazza Don Carlo di Giuseppe Verdi inaugura domenica 24 novembre 2019 la Stagione Lirica e Balletto 2019-2020 del Teatro La Fenice. Lo spettacolo, con la regia di Robert Carsen e la direzione del Maestro Myung-Whun Chung, vede un cast prestigioso: Piero Pretti, Maria Agresta, Alex Esposito, Julian Kim, Veronica Simeoni. In attesa di questo evento la Fenice, in sinergia con l’Associazione Piazza San Marco e con i commercianti del Distretto del Commercio di Mestre, ha dato vita al progetto LaFeniceinPiazza trasportando l’opera di Verdi nelle vetrine del cuore di Venezia e di Mestre per condividere le emozioni e la bellezza dell’inaugurazione con un pubblico sempre più ampio e diversificato. Dal 24 ottobre al 24 novembre l’atmosfera della prima alla Fenice pervaderà Piazza San Marco e Piazza Ferretto, coinvolgendo molti esercizi commerciali che esporranno una vetrofania dedicata al Don Carlo, ideata da Massimo Checchetto, oltre ad oggetti di scena, foto e locandine provenienti dall’archivio storico del Teatro. Sono previsti quattro incontri culturali legati alle tematiche dell’opera verdiana. Il primo appuntamento avrà luogo mercoledì 30 ottobre alle ore 18.00 a Mestre, presso il Museo M9, dove lo scrittore Alberto Toso Fei racconterà la storia della Fenice attraverso curiosi aneddoti e di seguito il Sovrintendente Fortunato Ortombina illustrerà il Don Carlo. Il secondo incontro si terrà al The Gritti Palace, mercoledì 6 novembre alle ore 18.00, e vedrà protagonisti lo scrittore Giovanni Montanaro e l’attrice Ottavia Piccolo, che esploreranno il rapporto padre e figlio nella letteratura. -

LIEDER ALIVE! 2012 Overview

LIEDER ALIVE! MASTER WORKSHOP AND CONCERT SERIES MAXINE BERNSTEIN director MASTER ARTISTS A ground-breaking program in the teaching of German Lieder Thomas Hampson 2008 Marilyn Horne 2009 June Anderson 2011 Håkan Hagegård 2012 Program Overview AFFILIATED MASTER ARTIST LIEDER ALIVE! was founded in 2007 by Maxine Bernstein to re-invigorate the teaching and Christa Ludwig performance of German Lieder, songs mainly from the Romantic Era of music composed for a solo singer and piano, and frequently set to great poetry. Our “graduate level” program brings CONTRIBUTING ARTISTS outstanding master artists together with highly accomplished emerging and established Heidi Melton, soprano Eleazar Rodriquez, tenor professionals. Such a program, devoted exclusively to this important artistic genre, is unique in Kindra Scharich, mezzo-soprano America. All of our extraordinary master artists, and our supremely gifted workshop participants, Katherine Tier, mezzo-soprano are aiding in our purpose of keeping Lieder where it belongs—alive! Ji Young Yang, soprano ADVISORY BOARD Håkan Hagegård has graciously consented to bring his innovative Singers' Studio to us for an David Bernstein, Honorary Chair intensive five-day program that will be held in the Music Salon at Salle Pianos, and concluding Alison Pybus, Executive Chair with a public Master Class in the grand Concert Hall at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music, Vice President, IMG Artists on September 8, 2012. John Parr Collaborative Pianist, Master Coach We were honored to welcome June Anderson who sang a Benefit Concert on Friday, October 14, San Francisco Opera Center then taught The Art of Singing, opening with a public Master Class on Saturday, October 15, 2011, Assistant to Music Director and Casting Director and continuing with a three-day private teaching intensive. -

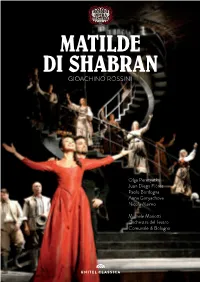

Gioachino Rossini

MATILDE DI SHABRAN GIOACHINO ROSSINI Olga Peretyatko Juan Diego Flórez Paolo Bordogna Anna Goryachova Nicola Alaimo Michele Mariotti Orchestra del Teatro Comunale di Bologna GIOACHINO ROSSINI MATILDE DI SHABRAN Conductor Michele Mariotti “There truly is a Rossini miracle!” (Deutschlandradio). Acclaiming Orchestra Orchestra del Teatro the mastery of tenorissimo Juan Diego Flórez and the breathtaking Comunale di Bologna young soprano Olga Peretyatko in the lead roles, the press hailed Chorus Coro del Teatro Comunale di Bologna the premiere of Rossini’s Matilde di Shabran at the Rossini Opera Chorus Master Lorenzo Fratini Festival in Pesaro as the “high point of the festival” (the Berlin daily Der Tagesspiegel). Matilde di Shabran Olga Peretyatko Matilde di Shabran was given its world premiere performance in Edoardo Anna Goryachova Rome in 1821. A genuine international hit, it was staged in Vienna, Raimondo Lopez Marco Filippo Romano London, Paris, New York and throughout Italy all before 1830. The Corradino Juan Diego Flórez music of Rossini’s last “opera semiseria” – thus half serious and half Ginardo Simon Orfila comic – contains a succession of beguiling ensemble pieces. The plot Aliprando Nicola Alaimo revolves around the knight Corradino, who has withdrawn to his castle Isidoro Paolo Bordogna and professes to hate his fellow humans. When he meets Matilde di Contessa d’Arco Chiara Chialli Shabran, however, he experiences unknown emotions that have Egoldo Giorgio Misseri nothing to do with hatred... Rodrigo Luca Visani Leading the Orchestra del Teatro Comunale di Bologna, conductor Staged by Mario Martone Michele Mariotti commands an ideal ensemble of singers: while Juan Diego Flórez, “perhaps the best Rossini tenor of our time” Video Director Tiziano Mancini (Deutschlandradio), sings the role of Corradino, that of Matilde is “gorgeously sung by Olga Peretyatko” (The New York Times). -

La Traviata Synopsis 5 Guiding Questions 7

1 Table of Contents An Introduction to Pathways for Understanding Study Materials 3 Production Information/Meet the Characters 4 The Story of La Traviata Synopsis 5 Guiding Questions 7 The History of Verdi’s La Traviata 9 Guided Listening Prelude 12 Brindisi: Libiamo, ne’ lieti calici 14 “È strano! è strano!... Ah! fors’ è lui...” and “Follie!... Sempre libera” 16 “Lunge da lei...” and “De’ miei bollenti spiriti” 18 Pura siccome un angelo 20 Alfredo! Voi!...Or tutti a me...Ogni suo aver 22 Teneste la promessa...” E tardi... Addio del passato... 24 La Traviata Resources About the Composer 26 Online Resources 29 Additional Resources Reflections after the Opera 30 The Emergence of Opera 31 A Guide to Voice Parts and Families of the Orchestra 35 Glossary 36 References Works Consulted 40 2 An Introduction to Pathways for Understanding Study Materials The goal of Pathways for Understanding materials is to provide multiple “pathways” for learning about a specific opera as well as the operatic art form, and to allow teachers to create lessons that work best for their particular teaching style, subject area, and class of students. Meet the Characters / The Story/ Resources Fostering familiarity with specific operas as well as the operatic art form, these sections describe characters and story, and provide historical context. Guiding questions are included to suggest connections to other subject areas, encourage higher-order thinking, and promote a broader understanding of the opera and its potential significance to other areas of learning. Guided Listening The Guided Listening section highlights key musical moments from the opera and provides areas of focus for listening to each musical excerpt. -

Akhnaten 12:55Pm | November 23

AKHNATEN 12:55PM | NOVEMBER 23 2019-2020 RICHARD HUBERT SMITH / ENGLISH NATIONAL OPERA NATIONAL ENGLISH / SMITH HUBERT RICHARD Met Opera AT THE PARAMOUNT THEATER The Paramount Theater is pleased to bring the award-winning 2019-2020 Met Opera Live in HD season, in its 14th year, to Charlottesville. This season will feature ten transmissions from the Met’s stage, including three new productions and two Met premieres. Pre-opera lectures will be held again this season and will take place in the auditorium (see website for lecture times and details). Doors to the auditorium will close during the lecture and will re-open for audience seating prior to the start of the broadcast. NEW PRODUCTIONS Wozzeck* • The Gershwins’ Porgy and Bess* Der Fliegende Holländer* REVIVALS Turandot • Manon • Madama Butterfly Tosca • Maria Stuarda MET PREMIERES Akhnaten* • Agrippina* *First Time in HD TICKETING & SUBSCRIPTIONS July 11 - On Sale to Met Members July 15 - On Sale to Paramount Star Circle Members July 17 - On Sale to all Paramount Members July 19 - On Sale to General Public Single Event Pricing $25 Adult, $23 Senior, $18 Student Subscription Pricing Reserved seats for all performances. $225 Adult, $207 Senior, $162 Student Box Office 215 East Main Street, Charlottesville, VA 22902 Monday - Friday 10AM - 2PM 434-979-1333 www.theparamount.net All tickets go on sale at 10:00AM on the dates specified above. Subscribers from previous seasons will have their preferred seat locations held throughout the duration of the pre-sale. If not renewed, seat locations will be released at 10:00AM on July 19, 2019. -

1. Early Years: Maria Before La Callas 2. Metamorphosis

! 1. EARLY YEARS: MARIA BEFORE LA CALLAS Maria Callas was born in New York on 2nd December 1923, the daughter of Greek parents. Her name at birth was Maria Kalogeropoulou. When she was 13 years old, her parents separated. Her mother, who was ambitious for her daughter’s musical talent, took Maria and her elder sister to live in Athens. There Maria made her operatic debut at the age of just 15 and studied with Elvira de Hidalgo, a Spanish soprano who had sung with Enrico Caruso. Maria, an intensely dedicated student, began to develop her extraordinary potential. During the War years in Athens the young soprano sang such demanding operatic roles as Tosca and Leonore in Beethoven’s Fidelio. In 1945, Maria returned to the USA. She was chosen to sing Turandot for the inauguration of a prestigious new opera company in Chicago, but it went bankrupt before the opening night. Yet fate turned out to be on Maria’s side: she had been spotted by the veteran Italian tenor, Giovanni Zenatello, a talent scout for the opera festival at the Verona Arena. Callas made her Italian debut there in 1947, starring in La Gioconda by Ponchielli. Her conductor, Tullio Serafin, was to become a decisive force in her career. 2. METAMORPHOSIS After Callas’ debut at the Verona Arena, she settled in Italy and married a wealthy businessman, Giovanni Battista Meneghini. Her influential conductor from Verona, Tullio Serafin, became her musical mentor. She began to make her name in grand roles such as Turandot, Aida, Norma – and even Wagner’s Isolde and Brünnhilde – but new doors opened for her in 1949 when, at La Fenice opera house in Venice, she replaced a famous soprano in the delicate, florid role of Elvira in Bellini’s I puritani. -

Jessica Pratt - Soprano

Jessica Pratt - Soprano Jessica Pratt est considérée comme l’une des meilleures interprètes de Bel cantos, même des plus difficiles du répertoire. Depuis ses débuts européens en 2007 dans Lucia di Lammermoor, la carrière de Jessica comprend des performances dans des théâtres et festivals comme le Metropolitan Opera New York, Teatro alla Scala of Milan, Gran Teatre Liceu of Barcelona, Zurich Opera, Deutsche Oper Berlin, le Vienna State Opera et le Royal Opera House Covent Garden. Elle a travaillé avec des chefs d’orchestre comme Daniel Oren, Nello Santi, Kent Nagano, Sir Colin Davis, Giacomo Sagripanti, Gianandrea Noseda, Carlo Rizzi, Roberto Abbado, Wayne Marshall et Christian Thielemann. Le répertoire de Jessica compte plus de 30 rôles différents, dont le plus célèbre est Lucia Ashton de Lucia di Lammermoor de Gaetano Donizetti dans plus de 27 productions, suivi de Amima de La Sonnambula de Vincenzo Bellini et Elvira de I Puritani du même compositeur. Elle est éGalement spécialiste du répertoire de Rossini : invitée fréquemment au Rossini Opera Festival à Pesaro, Jessica a tenu 12 rôles dans des opéras de ce compositeur, notamment les rôles principaux de Semiramide, Armida, Adelaide de BorGoGna, plus récemment Desdemona dans Otello au Gran Teatre de Liceu de Barcelone et Rosina dans Barbiere di Siviglia à l’Arena de Vérone. Un autre compositeur au centre du travail de Jessica est Gaetano Donizetti. Elle a fait ses débuts à La Scala de Milan avec La Prima Donna in Convenienze ed Inconvenienze Teatrali et plus tard, Lucia di Lammermoor. La saison dernière, elle a ajouté 4 nouvelles œuvres de Donizetti à son répertoire : La Fille du Regiment à l’Opera Las Palmas, Don Pasquale à l’ABAO de Bilbao, L'elisir d'amore au Gran Theatre Liceu de Barcelone et le rôle principal de Rosmonda d'Ingliterra en version de concert pour l’Opera di Firenze. -

Meistersinger Von Nürnberg

RICHARD WAGNERʼS DIE MEISTERSINGER VON NÜRNBERG Links to resources and lesson plans related to Wagnerʼs opera, Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg. Classical Net http://www.classical.net/music/comp.lst/wagner.php Includes biographical information about Richard Wagner. Dartmouth: “Under the Linden Tree” by Walter von der Vogelweide (1168-1228) http://www.dartmouth.edu/~german/German9/Vogelweide.html Original text in Middle High German, with translations into modern German and English. Glyndebourne: An Introduction to Wagnerʼs Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tXPY-4SMp1w To accompany the first ever Glyndebourne production of Wagner's Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg (the long held dream of the founder John Christie) Professor Julian Johnson of London Holloway University gives us some studied insights into the work. Glyndebourne: Scale and Detail Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg https://vimeo.com/24310185 Get a glimpse into putting on this epic scale Opera from Director David McVicar, Designer Vicki Mortimer, Lighting designer Paule Constable, and movement director Andrew George. Backstage and rehearsal footage recorded at Glyndebourne in May 2011. Great Performances: Fast Facts, Long Opera http://www.pbs.org/wnet/gperf/gp-met-die-meistersinger-von-nurnberg-fast-facts-long-opera/3951/ Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg (“The Master-Singer of Nuremberg”) received its first Great Performances at the Met broadcast in 2014. The Guardian: Die Meistersinger: 'It's Wagner's most heartwarming opera' http://www.theguardian.com/music/2011/may/19/die-meistersinger-von-nurnberg-glyndebourne Director David McVicar on "looking Meistersinger squarely in the face and recognising the dark undercurrents which are barely beneath the surface." "When Wagner composed the opera in the 1860s, he thought he was telling a joyous human story," he says.