Amphibious Operations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scott Wadsworth Heaney Member, Board of Directors World Affairs Council of Connecticut

Scott Wadsworth Heaney Member, Board of Directors World Affairs Council of Connecticut Scott Wadsworth Heaney was born in Hartford Connecticut on June 3, 1973 and was raised in Glastonbury, Connecticut where he graduated from Glastonbury High School in 1992. From 1992-1996, Scott attended Springfield College in Springfield, Massachusetts earning a Bachelors of Science Degree in Psychology. While at Springfield College, Scott was the Student assistant to the Director of Alumni Relations, was a member of both the track and cross country teams, and was involved in numerous extra curricular activities on and off campus. Scott was also a founding member of the Springfield College Student Alumni Council and the Springfield College Veteran’s Day Committee. In 1993, Scott was accepted into the Marine Corps Platoon Leader’s Class Officer Candidate Program. Upon graduation, he was commissioned a Second Lieutenant in the United States Marine Corps. In September 1996, he reported to the Marine Corps Combat Development Command in Quantico, Virginia for The Basic School (TBS), a grueling six month officer development program which all Marine Corps officers must complete after after becoming a commissioned officer. Having graduated from the Basic Logistics Officer’s Course, The Landing Force Logistics Officers Course and the Joint Maritime Pre-positioned Force Staff Planner’s Course, Scott became a logistics officer and was assigned to his first duty station in California. In 1998, Scott reported to First Marine Corps Division in Camp Pendleton California to serve in the infantry battalion as the Assistant Logistics Officer for First Battalion First Marines (1/1). During his tour from 1999-2000, Scott’s battalion completed a six month deployment on the USS Peleliu operating in Korea, Thailand, United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia and conducting peace keeping operations in East Timor. -

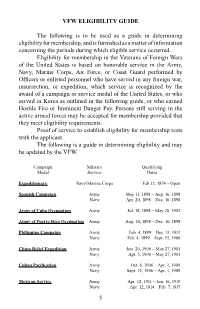

Eligibility Guide.Pdf

VFW ELIGIBILITY GUIDE The following is to be used as a guide in determining eligibility for membership, and is furnished as a matter of information concerning the periods during which eligible service occurred. Eligibility for membership in the Veterans of Foreign Wars of the United States is based on honorable service in the Army, Navy, Marine Corps, Air Force, or Coast Guard performed by Officers or enlisted personnel who have served in any foreign war, insurrection, or expedition, which service is recognized by the award of a campaign or service medal of the United States, or who served in Korea as outlined in the following guide, or who earned Hostile Fire or Imminent Danger Pay. Persons still serving in the active armed forces may be accepted for membership provided that they meet eligibility requirements. Proof of service to establish eligibility for membership rests with the applicant. The following is a guide in determining eligibility and may be updated by the VFW. Campaign Military Qualifying Medal Service Dates Expeditionary Navy/Marine Corps Feb 12, 1874 – Open Spanish Campaign Army May 11, 1898 – Aug. 16, 1898 Navy Apr. 20, 1898 – Dec. 10, 1898 Army of Cuba Occupation Army Jul. 18, 1898 – May 20, 1902 Army of Puerto Rico Occupation Army Aug. 14, 1898 – Dec. 10, 1898 Philippine Campaign Army Feb. 4, 1899 – Dec. 31, 1913 Navy Feb. 4, 1899 – Sept. 15, 1906 China Relief Expedition Army Jun. 20, 1900 – May 27, 1901 Navy Apr. 5, 1900 – May 27, 1901 Cuban Pacification Army Oct. 6, 1906 – Apr. 1, 1909 Navy Sept. 12, 1906 – Apr. -

OATSD-PA Memorandum on Beginning of Rwandan Genocide

Digital Commons @ George Fox University David Rawson Collection on the Rwandan Genocide Archives and Museum 4-12-1994 OATSD-PA Memorandum on Beginning of Rwandan Genocide N/A Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/rawson_rwanda Recommended Citation N/A, "OATSD-PA Memorandum on Beginning of Rwandan Genocide" (1994). David Rawson Collection on the Rwandan Genocide. 241. https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/rawson_rwanda/241 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Archives and Museum at Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in David Rawson Collection on the Rwandan Genocide by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. .SENT BY: :13- 4-94 3=55PM 497116805380~ 202 647 0122i# 2 HQUSEUCOM Public Affairs 12 April 1994 MEMORANDUM FOR OATSD-PA (CAPT Doubleday) SUBJECT: DISTANT RUNNER UPDATE WRAP-UP (RWANDA NEO) 1. In support of today's Press Brief, the following information on the Rwanda NEO (DISTANT RUNNER) is provided for your use: • The u.s. European command forward deployed u.s. Marine Corps, Navy and Air Force forces Saturday, April 9 1 to Burundi and Kenya as a precautionary measure in the event a non-combatant evacuation (NEO) was required for approximately 250 u.s. citizens in Rwanda. That country experienced a drastic escalation of violence at the end of last week that left many thousands dead. We are redeploying our forces today. • our u.s. Embassy in Rwanda completed an ordered departure by overland convoys, but our forward deployed forces airlifted 242 u.s. -

Autumn 2007 Full Issue the .SU

Naval War College Review Volume 60 Article 1 Number 4 Autumn 2007 Autumn 2007 Full Issue The .SU . Naval War College Follow this and additional works at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review Recommended Citation Naval War College, The .SU . (2007) "Autumn 2007 Full Issue," Naval War College Review: Vol. 60 : No. 4 , Article 1. Available at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol60/iss4/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Naval War College Review by an authorized editor of U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Autumn 2007 60, Number 4 Volume Naval War College: Autumn 2007 Full Issue NAVAL WAR COLLEGE REVIEW Published by U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons, 2007 NAVAL WAR COLLEGE REVIEW Autumn 2007 R COL WA LEG L E A A I V R A N O T C I V I R A M S U S E B I T A T R T I H S E V D U E N T I Color profile: Disabled Composite Default screen Naval War College Review, Vol. 60 [2007], No. 4, Art. 1 Cover The Kongo-class guided-missile destroyer JDS Chokai (DDF 176) of the Japan Mar- itime Self-Defense Force alongside USS Kitty Hawk (CV 63) on 10 December 2002. The scene is evocative of one of the many levels at which the “thousand-ship navy,” examined in detail in this issue by Ronald E. -

USS STOCKDALE (DDG 106) MAGAZINE April

HONOR USS STOCKDALE (DDG 106) MAGAZINE April. 2019 Vol. 1 Issue 4 CONTENTS / // A Message to the Crew From the Commanding Officer 17 “Shipmates, with all this talk about canceled port calls, a second beer day, and the uncertainty with our schedule, I want to discuss the benefits of adversity with you. Adversity is usually not a welcome word due to Commanding Officer its direct association with pain. But it is important not to shy away from Cmdr. Leonard Leos adversity because adversity and the struggles and hardships that come with it make you stronger. Facing adversity builds confidence and will Executive Officer put you on a path to counter greater adversity. As Sailors, we are tested Cmdr. Brandon Booher daily all types of physical and mental adversity, such as working flight operations, standing watch, prepping food in the galley, or countless Collateral Duty Public hours of drills. Many of these shipboard duties are carried out in extreme Affairs Officer conditions and deprive us many hours of precious sleep. Attitude is very Ensign Alison Flynn important in dealing with adversity. Instead of feeling like a victim or feeling sorry for yourself, it is important to carry a tough, positive attitude. Editor/Designer This attitude becomes the foundation for creating a special breed of Sailor MC2 Abigayle Lutz who can tackle any challenges a Dynamic Force Employment has to offer. 4 MARCH IN REVIEW Our Sister Service, the Marine Corps, prides themselves on working in / TAKE A GLIMPSE AT MARCH the worst conditions having the crappiest gear and having the highest casualty rates. -

Preliminary Draft

Title preliminary D R A F T -- 1/91 D-Day, Orange Beach 3 BLILIOU (PELELIU) HISTORICAL PARK STUDY January, 1991 Preliminary Draft Prepared by the Government of Palau and the http://www.nps.gov/pwro/piso/peleliu/title.htm[7/24/2013 3:39:42 PM] Title National Park Service TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Background and Purpose BLILIOU (PELELIU) Study Setting Tourism Land Ownership and Tenure in Palau Compact of Free Association Bliliou Consultation and Coordination World War II Relics on Bliliou Natural Resources on Bliliou Bliliou National Historic Landmark Historical Park - Area Options Management Plan Bliliou Historical Park Development THE ROCK ISLANDS OF PALAU http://www.nps.gov/pwro/piso/peleliu/title.htm[7/24/2013 3:39:42 PM] Title Description The Reefs The Islands Soils Vegetation The Lagoon Marine Lakes Birdlife Scenery Archeology Existing Uses Recreation Fishing Land Use Conserving and Protecting Rock Islands Resources Management Concepts Boundary Options PARK PROTECTION POSSIBILITIES BIBLIOGRAPHY APPENDICES Appendix A Appendix B http://www.nps.gov/pwro/piso/peleliu/title.htm[7/24/2013 3:39:42 PM] Title Management Option Costs LIST OF FIGURES Figure Location Map, The Pacific Ocean 1 Figure States of the Republic of Palau 2 Figure Peleliu 1944; Bliliou Today 3 Figure Land Tenure 4 Figure Remaining Sites and Features, 1944 Invasion 5 Figure Detail 1, Scarlet Beach 6 Figure Detail 2, Purple Beach 7 Figure Detail 3, Amber Beach 8 Figure Detail 4, Amber Beach & Bloody Nose Ridge 9 Figure Detail 5, White and Orange Beaches 10 Figure Bloody -

VFW Eligibility Information

Rev. 07/27/16 VFW Eligibility Information The fundamental differences between our organization and other veterans organizations, and one in which we take great pride, are our eligibility qualifications. There are three primary requisites for membership in the Veterans of Foreign Wars of the United States: (1) U.S. Citizen or U.S. National (2) Honorable service in the Armed Forces of the United States (3) Service entitling the applicant to the award of a recognized campaign medal or as set forth in the Congressional Charter and By-Laws and Manual of Procedure and Ritual. Sec. 103 -- ELECTION: Applications. After the applicant has filled out the application card, it should be provided to the post adjutant or quartermaster, together with the dues (and admission fee, if applicable). A receipt shall be given to the applicant. An applicant may be recommended after eligibility has been fully determined by the post reviewing committee. With respect to a department member-at-large, the department headquarters is responsible for the eligibility determination. The original application of every member will be retained on file with the adjutant. Balloting on Applications. Before voting on the application during a post meeting, the commander shall allow the members present an opportunity to state their objections, if any, to the admission of the applicant. Unless one member present shall request a written ballot, a vote shall be taken and a majority of the votes cast shall decide acceptance or rejection of the application. Rejection of Applicant. Should an applicant be rejected by the post, the admission fee and dues shall be returned. -

NAVMC 2922 Unit Awards Manual (PDF)

DEPARTMENT OF THE NAVY HEADQUARTERS UNITED STATES MARINE CORPS 2008 ELLIOT ROAD QUANTICO, VIRGINIA 22134-5030 IH REPLY REFER TO: NAVMC 2 922 MMMA JAN 1 C IB# FOREWORD 1. Purpose. To publish a listing of all unit awards that have been presented to Marine Corps units since the beginning of World War II. 2. Cancellation. NAVMC 2922 of 17 October 2011. 3. Information. This NAVMC provides a ready reference for commanders in determining awards to which their units are entitled for specific periods of time, facilitating the updating of individual records, and accommodating requests by Marines regarding their eligibility to wear appropriate unit award ribbon bars. a . Presidential Unit Citation (PUC), Navy Unit Citation (NUC), Meritorious Unit Citation (MUC) : (1) All personnel permanently assigned and participated in the action(s) for which the unit was cited. (2) Transient, and temporary duty are normally ineligible. Exceptions may be made for individuals temporarily attached to the cited unit to provide direct support through the particular skills they posses. Recommendation must specifically mention that such personnel are recommended for participation in the award and include certification from the cited unit's commanding officer that individual{s) made a direct, recognizable contribution to the performance of the services that qualified the unit for the award. Authorized for participation by the awarding authority upon approval of the award. (3) Reserve personnel and Individual Augmentees <IAs) assigned to a unit are eligible to receive unit awards and should be specifically considered by commanding officers for inclusion as appropriate, based on the contributory service provided, (4) Civilian personnel, when specifically authorized, may wear the appropriate lapel device {point up). -

Military Medals and Awards Manual, Comdtinst M1650.25E

Coast Guard Military Medals and Awards Manual COMDTINST M1650.25E 15 AUGUST 2016 COMMANDANT US Coast Guard Stop 7200 United States Coast Guard 2703 Martin Luther King Jr Ave SE Washington, DC 20593-7200 Staff Symbol: CG PSC-PSD-ma Phone: (202) 795-6575 COMDTINST M1650.25E 15 August 2016 COMMANDANT INSTRUCTION M1650.25E Subj: COAST GUARD MILITARY MEDALS AND AWARDS MANUAL Ref: (a) Uniform Regulations, COMDTINST M1020.6 (series) (b) Recognition Programs Manual, COMDTINST M1650.26 (series) (c) Navy and Marine Corps Awards Manual, SECNAVINST 1650.1 (series) 1. PURPOSE. This Manual establishes the authority, policies, procedures, and standards governing the military medals and awards for all Coast Guard personnel Active and Reserve and all other service members assigned to duty with the Coast Guard. 2. ACTION. All Coast Guard unit Commanders, Commanding Officers, Officers-In-Charge, Deputy/Assistant Commandants and Chiefs of Headquarters staff elements must comply with the provisions of this Manual. Internet release is authorized. 3. DIRECTIVES AFFECTED. Medals and Awards Manual, COMDTINST M1650.25D is cancelled. 4. DISCLAIMER. This guidance is not a substitute for applicable legal requirements, nor is it itself a rule. It is intended to provide operational guidance for Coast Guard personnel and is not intended to nor does it impose legally-binding requirements on any party outside the Coast Guard. 5. MAJOR CHANGES. Major changes to this Manual include: Renaming of the manual to distinguish Military Medals and Awards from other award programs; removal of the Recognition Programs from Chapter 6 to create the new Recognition Manual, COMDTINST M1650.26; removal of the Department of Navy personal awards information from Chapter 2; update to the revocation of awards process; clarification of the concurrent clearance process for issuance of awards to Coast Guard Personnel from other U.S. -

Cageprisoners Cageprisoners

CAGEPRISONERS BEYOND THE LAW – The War on Terror’s Secret Network of Detentions AFRICA East Africa PRISON NAME LOCATION CONTROL SITE CONDITIONS DETAINEES STATUS Unknown Unknown East African Arabic Muhammad al-Assad was taken from his - Muhammad al- Suspected speaking jailers, with home in Tanzania and was only told that Assad Proxy Detention possibly Somali or orders had come from very high sources that Facility Ethiopian accents. he should be taken. The next thing he knew he had been taken on a plane for three hours to a very hot place. His jailers who would take him for interrogation spoke Arabic with a Somali or Ethiopian accent and had been served with bread that was typical of those regions. He was held in this prison for a period of about 2 weeks during which time he was interrogated by an English-speaking woman a white western man who spoke good Arabic. 1 Egypt Al Jihaz / State Situated in Nasr State Security Many former detainees have consistently - Ahmad Abou El Confirmed Security City which is in Intelligence approximated that cells within this centre are Maati Proxy Detention Intelligence an eastern roughly four feet wide and ten foot long, with - Maajid Nawaz Facility National suburb of Cairo many packed together, and with many more - Reza Pankhurst Headquarters detainees held within a small area. A torture - Ian Nesbit room is also alleged to be close by to these cells so that detainees, even when not being tortured themselves, were privy to the constant screams of others. Abou Zabel 20 miles from State Security El Maati reports that he spent some weeks in - Ahmad Abou El Confirmed the centre of Intelligence this prison. -

Manufacturers Responsible for Quality Control HONOLULU - Johnny Was Given a Do Better

5 Posture statemen Dental health Exercise Super Squad Lehman addresses Dependent dentistry program Physical program Competition Squad House Armed Service<, provides free exams builds up Marines attempts third title budget committee and fluoride treatments "can do" attitude in five years Page A-2 Page A-7 Page B-1 Page B-4 HAWAII MARINE Vol un limy payment for delivery to MCAS housing /S 1 per four week period. VOL. 11 NO. 17 KANEOHE BAY. HAW.AIL APRIL 28, 1982 TWENTYTWO PAGES Aviators sought 'HNC, WASHINGTON - The Marine Corps is looking for officers interested in becoming Naval Aviators. Manpower officials here stress that although the Naval Flight Officer community is filled, a shortage of NAs (pilots) exists. -There are many quality officers in the Marine Corps. We feel many would Make fine Naval Aviators and would like them to apply," said a manpower official. Unrestricted regular officers on active duty, and unrestricted reserve officers on active or inactive duty are eligible. Manpower officials will also consider officers accepted for NFO training and later found qualified for NA training, as long as they applied for NA training prior to THE JOURNEY BEGINS - Marines of BLT 3/3 HMM-185 amphibious unit departed on its annual six-month beginning NFO training and MSSG-31 say goodbye to family and loved ones before deployment Thursday. (Photo by Sgt Chris Taylor) assignments. boarding the USS Peleliu at Pearl Harbor. The Marine Current NFO trainees cannot apply for cross-training to NA status. However, NFOs who have completed at least three years in Marines depart Hawaii after that community may apply. -

“Asia-Pacific Trends: a U.S. Pacom Perspective"

Asia-Pacific Trends: A U.S. PACOM Perspective By Admiral Timothy J. Keating Issues and Insights Vol. 7 – No. 14 Honolulu, Hawaii September 2007 Pacific Forum CSIS Based in Honolulu, the Pacific Forum CSIS (www.pacforum.org) operates as the autonomous Asia-Pacific arm of the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, DC. The Forum’s programs encompass current and emerging political, security, economic, business, and oceans policy issues through analysis and dialogue undertaken with the region’s leaders in the academic, government, and corporate areas. Founded in 1975, it collaborates with a broad network of research institutes from around the Pacific Rim, drawing on Asian perspectives and disseminating project findings and recommendations to opinion leaders, governments, and members of the public throughout the region. Table of Contents Page “Asia-Pacific Trends: A U.S. PACOM Perspective” By Admiral Timothy J. Keating 1 About the Author A-1 iii iv Asia-Pacific Trends: A U.S. PACOM Perspective by Admiral Timothy J. Keating Admiral Timothy J. Keating, Commander, U.S. Pacific Command (PACOM) spoke at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in Washington, D.C. on July 24, 2007. He was introduced by his co-hosts, Pacific Forum CSIS President Ralph A. Cossa and CSIS Senior Vice President Stephen Flanagan. Good afternoon everyone. Konichiwa. Good to see you all, some good friends and old friends. I thought we’d talk a little bit about the Pacific from a relatively new and a very old guy’s perspective. I’ll give you a stereo broadcast, a then and now perspective.