Contradiction Between Techniques and Aesthetics in Early Modernism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bauhaus 1 Bauhaus

Bauhaus 1 Bauhaus Staatliches Bauhaus, commonly known simply as Bauhaus, was a school in Germany that combined crafts and the fine arts, and was famous for the approach to design that it publicized and taught. It operated from 1919 to 1933. At that time the German term Bauhaus, literally "house of construction" stood for "School of Building". The Bauhaus school was founded by Walter Gropius in Weimar. In spite of its name, and the fact that its founder was an architect, the Bauhaus did not have an architecture department during the first years of its existence. Nonetheless it was founded with the idea of creating a The Bauhaus Dessau 'total' work of art in which all arts, including architecture would eventually be brought together. The Bauhaus style became one of the most influential currents in Modernist architecture and modern design.[1] The Bauhaus had a profound influence upon subsequent developments in art, architecture, graphic design, interior design, industrial design, and typography. The school existed in three German cities (Weimar from 1919 to 1925, Dessau from 1925 to 1932 and Berlin from 1932 to 1933), under three different architect-directors: Walter Gropius from 1919 to 1928, 1921/2, Walter Gropius's Expressionist Hannes Meyer from 1928 to 1930 and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe Monument to the March Dead from 1930 until 1933, when the school was closed by its own leadership under pressure from the Nazi regime. The changes of venue and leadership resulted in a constant shifting of focus, technique, instructors, and politics. For instance: the pottery shop was discontinued when the school moved from Weimar to Dessau, even though it had been an important revenue source; when Mies van der Rohe took over the school in 1930, he transformed it into a private school, and would not allow any supporters of Hannes Meyer to attend it. -

Seagram Building, First Floor Interior

I.andmarks Preservation Commission october 3, 1989; Designation List 221 IP-1665 SEAGRAM BUIIDING, FIRST FLOOR INTERIOR consisting of the lobby and passenger elevator cabs and the fixtures and interior components of these spaces including but not limited to, interior piers, wall surfaces, ceiling surfaces, floor surfaces, doors, railings, elevator doors, elevator indicators, and signs; 375 Park Avenue, Manhattan. Designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe with Philip Johnson; Kahn & Jacobs, associate architects. Built 1956-58. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 1307, Lot 1. On May 17, 1988, the landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Seagram Building, first floor interior, consisting of the lobby and passenger elevator cabs and the fixtures and interior components of these spaces including but not limited to, interior piers, wall surfaces, ceiling surfaces, floor surfaces, doors, railings, elevator doors, elevator indicators, and signs; and the proposed designation of the related I.and.mark Site (Item No. 2). The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. Twenty witnesses, including a representative of the building's owner, spoke in favor of designation. No witnesses spoke in opposition to designation. The Commission has received many letters in favor of designation. DFSCRIPI'ION AND ANALYSIS Summary The Seagram Building, erected in 1956-58, is the only building in New York City designed by architectural master Iudwig Mies van der Rohe. Constructed on Park Avenue at a time when it was changing from an exclusive residential thoroughfare to a prestigious business address, the Seagram Building embodies the quest of a successful corporation to establish further its public image through architectural patronage. -

EU Prize for Contemporary Architecture / Mies Van Der Rohe Award: a Tribute to Bauhaus

AT A GLANCE EU Prize for Contemporary Architecture / Mies van der Rohe Award: A tribute to Bauhaus The EU Prize for Contemporary Architecture (also known as the EU Mies Award) was launched in recognition of the importance and quality of European architecture. Named after German architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, a figure emblematic of the Bauhaus movement, it aims to promote functionality, simplicity, sustainability and social vision in urban construction. Background Mies van der Rohe was the last director of the Bauhaus school. The official lifespan of the Bauhaus movement in Germany was only fourteen years. It was founded in 1919 as an educational project devoted to all art forms. By 1933, when the Nazi authorities closed the school, it had changed location and director three times. Artists who left continued the work begun in Germany wherever they settled. Recognition by Unesco The Bauhaus movement has influenced architecture all over the world. Unesco has recognised the value of its ideas of sober design, functionalism and social reform as embodied in the original buildings, putting some of the movement's achievements on the World Heritage List. The original buildings located in Weimar (the Former Art School, the Applied Art School and the Haus Am Horn) and Dessau (the Bauhaus Building and the group of seven Masters' Houses) have featured on the list since 1996. Other buildings were added in 2017. The list also comprises the White City of Tel-Aviv. German-Jewish architects fleeing Nazism designed many of its buildings, applying the principles of modernist urban design initiated by Bauhaus. -

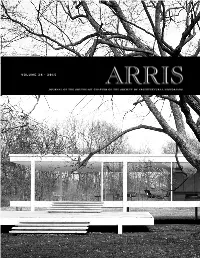

Architectural Photography, the Farnsworth House, and the Opaque Discourse of Transparency SARAH M

VOLUME 26 · 2015 JOURNAL OF THE SOUTHEAST CHAPTER OF THE SOCIETY OF ARCHITECTURAL HISTORIANS Volume 26 · 2015 1 Editors’ Note Articles 6 Madness and Method in the Junkerhaus: The Creation and Reception of a Singular Residence in Modern Germany MIKESCH MUECKE AND NATHANIEL ROBERT WALKER 22 Curtained Walls: Architectural Photography, the Farnsworth House, and the Opaque Discourse of Transparency SARAH M. DRELLER 40 The “Monster Problem”: Texas Architects Try to Keep it Cool Before Air Conditioning BETSY FREDERICK-ROTHWELL 54 Electrifying Entertainment: Social and Urban Modernization through Electricity in Savannah, Georgia JESSICA ARCHER Book Reviews 66 Cathleen Cummings, Decoding a Hindu Temple: Royalty and Religion in the Iconographic Program of the Virupaksha Temple, Pattadakal REVIEWED BY DAVID EFURD 68 Reiko Hillyer, Designing Dixie: Tourism, Memory, and Urban Space in the New South REVIEWED BY BARRY L. STIEFEL 70 Luis E, Carranza and Fernando L. Lara, Modern Architecture in Latin America: Art, Technology, and Utopia REVIEWED BY RAFAEL LONGORIA Field Notes 72 Preserving and Researching Modern Architecture Outside of the Canon: A View from the Field LYDIA MATTICE BRANDT 76 About SESAH ABSTRACTS Sarah M. Dreller Curtained Walls: Architectural Photography, the Farnsworth House, and the Opaque Discourse of Transparency Abstract This paper studies the creation, circulation, and reception of two groups of photographs of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s iconic Farnsworth House, both taken by Hedrich Blessing. The first set, produced for a 1951 Architectural Forum magazine cover story, features curtains carefully arranged according to the architect’s preferences; the Museum of Modern Art commis- sioned the second set in 1985 for a major Mies retrospective exhibition specifically because the show’s influential curator, Arthur Drexler, believed the curtains obscured Mies’ so-called “glass box” design. -

16 Bauhaus and Beyond Friday, March 20, 2020 1:45 PM

16 Bauhaus and Beyond Friday, March 20, 2020 1:45 PM Admin Remember, any photograph or image you don't create must be given attribution in EVERY post you use it in. It's fine to use designs from elsewhere, as long as you give credit. Possible format for virtual Expo during exam time: First half hour, everybody in Pod A host a Zoom room, demonstrate what they have, answer questions from folks in Pods B,C,D, who stroll between Zoom rooms. Next half hour, Pod B is host, etc. Zooms are open, can still invite family and friends online. http://www.rchoetzlein.com/website/artmap/ Fiell, Charlotte & Peter. Design of the 20th Century. Taschen America, 2012. AesDes2020 Page 1 Fiell, Charlotte & Peter. Design of the 20th Century. Taschen America, 2012. Everything changed around 1920. Modernist era began. Abstract shapes, unadorned surfaces, function rules 1914-1918 WORLD WAR I Economies changed Art changed See timelines Short discussion: What do you already know about Bauhaus? Bauhaus video Design in a Nutshell, from the British Open University: http://www2.open.ac.uk/openlearn/design_nutshell/index.php# Brian Douglas Hayes. Bauhaus: A History and Its Legacy, 2012. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xYrzrqB0B8I. 8:38 Bauhaus has roots in Deutscher Werkbund Still trying to integrate craftsmanship with industrialization: 1907 -1935. Big change in aesthetics. The Deutscher Werkbund (German Association of Craftsmen) is a German association of artists, architects, designers, and industrialists, established in 1907. The Werkbund became an important element in the development of modern architecture and industrial design, particularly in the later creation of the Bauhaus school of design. -

The 1914 Werkbund Debate Resolved: the Design and Manufacture of Frank O

The 1914 Werkbund Debate Resolved: The Design and Manufacture of Frank O. Gehry’s Guggenheim Museum, Bilbao Irene Nero Concern about McDonaldization in architecture is not new pride should dictate that goods be of fine quality, so as not to to architectural discourse.1 The terms of expression may be “pollute the visual environment.”4 different, but some of the important issues are fundamentally Van de Velde, another of the founding members, was also the same as those found at the core of the historic 1914 influenced by England’s Industrial Revolution, but this time, Werkbund debate between Hermann Muthesius and Henry van by its vocal opponent—John Ruskin. Van de Velde was in de Velde. This landmark debate serves as one of the earliest, if agreement with Muthesius that goods produced should be of not the earliest, example of publicly demonstrated concern high quality, but felt that handcrafting in the English Arts among modern architects regarding the origins of design and and Crafts tradition was more appropriate for establishing a manufacture of architecture.2 Primarily, at debate was the is- national identity.5 Both of the powerful Werkbund members sue of architecture becoming a standardized type-object, sub- agreed that quality was an issue in the production of German ject to ubiquitous distribution, versus architecture remaining goods, but had divergent ideas regarding their manufacture. an individualized, artistically-inspired creation. “Sameness” Manufactured goods, however, were not the only items under was an issue, simply because it was deemed an affront to the consideration at the Werkbund exhibition for standardization. creative process. -

Shifts in Modernist Architects' Design Thinking

arts Article Function and Form: Shifts in Modernist Architects’ Design Thinking Atli Magnus Seelow Department of Architecture, Chalmers University of Technology, Sven Hultins Gata 6, 41296 Gothenburg, Sweden; [email protected]; Tel.: +46-72-968-88-85 Academic Editor: Marco Sosa Received: 22 August 2016; Accepted: 3 November 2016; Published: 9 January 2017 Abstract: Since the so-called “type-debate” at the 1914 Werkbund Exhibition in Cologne—on individual versus standardized types—the discussion about turning Function into Form has been an important topic in Architectural Theory. The aim of this article is to trace the historic shifts in the relationship between Function and Form: First, how Functional Thinking was turned into an Art Form; this orginates in the Werkbund concept of artistic refinement of industrial production. Second, how Functional Analysis was applied to design and production processes, focused on certain aspects, such as economic management or floor plan design. Third, how Architectural Function was used as a social or political argument; this is of particular interest during the interwar years. A comparison of theses different aspects of the relationship between Function and Form reveals that it has undergone fundamental shifts—from Art to Science and Politics—that are tied to historic developments. It is interesting to note that this happens in a short period of time in the first half of the 20th Century. Looking at these historic shifts not only sheds new light on the creative process in Modern Architecture, this may also serve as a stepstone towards a new rethinking of Function and Form. Keywords: Modern Architecture; functionalism; form; art; science; politics 1. -

Die Architekturausstellung Als Kritische Form 2018

Die Architekturausstellung als kritische Form 1 Lehrstuhl für Architekturgeschichte und kuratorische Praxis EXTRACT “Die Architekturausstellung als kritische Form von Hermann Muthesius zu Rem Koolhaas” Wintersemester 2018/19 LECTURE 1 / 18 October 2018 Die Architekturausstellung als kritische Form. Vorgeschichte, Themen und Konzepte. Basic questions: - What is an architecture exhibition? - How can we exhibit architecture? - What does the architecture exhibition contribute to? Statements: - Exhibitions of architecture are part of a socio-political discourse. (See Toyo Ito’s curatorial take on the Architecture Biennale in Venice in 2012 http://www.domusweb.it/en/interviews/2012/09/03/toyo-ito-home-for-all.html) - Exhibitions of architecture are model-like presentations / They should present the new directions of the discipline. (“Critical” in this context of this lecture class means: exhibitions introducing a new theoretical and / or practical concept in contrast to existing traditions) PREHISTORY I. - Model Cabinets (Modellkammer), originally established as work tools for communication purposes and as educational tools for upcoming architects / engineers. Further aspect: building up an archive of technological inventions. - Example: The medieval collection of models for towers, gates, roof structures etc. in Augsburg, hosted by the Maximilianmuseum. - Originally these cabinets were only accessible for experts, professionals, not for public view. Sources of architecture exhibitions: - Technical and constructive materials (drawings, models). They tend to be private or just semi- public collections built up with education purposes. - The first public exhibitions of these models in the arts context didn’t happen until the end of the 18th century. Occasion: Charles de Wailly exhibited a model of a staircase in an arts exhibition in 1771. -

Heike Hambrock Marlene Moeschke

Heike Hambrock Marlene Moeschke - Mitarbeiterin? Das wiederentdeckte Werk der Bildhauerin und Architektin liefert neue Er kenntnisse über Hans Poelzigs Großes Schauspielhaus in Berlin. In Johann Jacob Bachofens Mutterrecht von 1861, dessen Lektüre für viele Künstler Anfang des 20. Jahrhunderts belegt ist, werden in einer archaisch anmutenden sexu ellen Symbolik Mann und Frau zum Gegensatzpaar Sonne (männlich, aktiv, Moder ne) und Mond (weiblich, passiv, Urmythos) stilisiert.1 In der Beschwörung eines >Urmythos< erklärt Bachofen die Frau zum universellen Lebenselement, Magna Ma ter, die im Einklang mit der Schöpfung der Natur stehe, deren Erkenntnis dem Mann das Gegenbild der Moderne verwehrt sei. Aufgrund ihrer weiblichen Natur sei die Frau allerdings weder fähig zu qualifiziertem wissenschaftlichen Arbeiten, noch zu technischer Höchstleistung oder künstlerischem Höhenflug. Im Sonnenmythos von Nietzsches Zarathustra vermag allein der Künstler als Geistesmensch, im Kampf mit sich selbst und der Materie Kunstwerke zu erschaffen. Die Frau gilt ge meinhin als Muse und Inspiration. Im Atelier des Künstlers wird sie nur als Modell oder Mutter der Kinder akzeptiert, ihre körperliche und geistige Präsenz ansonsten als Bedrohung der männlichen Energie wahrgenommen. Auf hohem künstlerischen Niveau findet sich der hier nur angedeutete Geschlechterkampf der Moderne in Os kar Kokoschkas Dramen und Grafikzyklen reflektiert.2 Allerdings kommt der um 1916 bis 1919 mit dem Architekten und damaligen Stadtbaurat Hans Poelzig (1869 1936) in Dresden freundschaftlich verkehrende Künstler zu der für die Zeit untypi schen Erkenntnis einer geschlechtlichen Gleichberechtigung. Der konservative Kunst und Architekturkritiker Karl Scheffler mochte demgegenüber der Frau nur die Rolle der >dilettierenden Hausfrau< zugestehen;3 selbst im Kunstgewerbe hatte sie als eigenständige Künstlerin in der wilhelminischen Gesellschaft keinen Platz. -

Inhalt Contents

Inhalt Contents 7 Prolog 7 Prologue 13 Vom Jugendstil zur Moderne 13 From Jugendstil to Modernism 19 Das Bauhaus in Weimar, Dessau und Berlin 19 The Bauhaus in Weimar, Dessau and Berlin 27 Berlin und die Moderne 27 Berlin and Modernism 63 Das Neue Bauen in Deutschland 63 New Building in Germany 127 Architektur der Neuen Sachlichkeit in Europa 127 The Architecture of new Objectivity in Europe 179 Internationaler Stil – 179 International Style – Modernes Bauen auf der ganzen Welt Modern Building all over the world 227 Epilog – Die Erben des Bauhauses 227 Epilogue – The Legacy of the Bauhaus 233 Anhang 233 Appendix Bauhaus.indd 5 12.09.18 12:58 Prolog Prologue Bauhaus.indd 7 12.09.18 12:58 8 Israel, Tel Aviv, Wohnhaus Recanati-Saporta, 1935/36, Salomon Liaskowski, Jakob Orenstein Israel, Tel Aviv, Residential building in Recanati-Saporta, 1935/36, Salomon Liaskowski, Jakob Orenstein Bauhaus.indd 8 12.09.18 12:58 Das »Bauhaus« war ursprünglich eine 1919 in Weimar gegründete The “Bauhaus” was originally an art school founded in Weimar in 1919. Kunstschule. Ihr Einfluss erwies sich jedoch als so bedeutend, dass Its influence, however, was so significant that in everyday speech the der Begriff heute umgangssprachlich mit verschiedenen Strömungen term is equated today with various modernist movements in architec- der Moderne in Architektur und Design in der ersten Hälfte des20 . ture and design in the first half of the 20th Century. This broader sense Jahrhunderts gleichgesetzt wird. In diesem erweiterten Sinn wurde of the word is relevant for the choice of buildings in this book. -

Bioscopic and Kinematic Books Studies on the Visualisation of Motion and Time in the Architectural Book Ca

Originalveröffentlichung in: Photoresearcher, 18 (2012), Nr. Oktober, S. 44-58 Bioscopic and Kinematic Books Studies on the Visualisation of Motion and Time in the Architectural Book ca. 1900–1935 Matthias Noell I. “Cinematic, moment-like composition” II. Movement in the automobile In the year 1923, El Lissitzky created the book anew. In Topography of Typography, the Russian In 1903 and 1930 two books found- artist propagated the “continuous page sequence” and opened up the concept of the “bioscop- ed on a common basic concept ic book” to discussion.1 The use of the term “bioscopic” – the Skladanowsky Brothers named were published in Berlin, and Zu- the film projector they used for the first time in Berlin in 1895 a “Bioscope” – is an indication rich and Leipzig respectively: Eine of the new interaction between the medial communication of information, optics and move- empfindsame Reise im Automobil by ment that the graphic design of the book was intended to implement. Otto Julius Bierbaum and Amerika Even though the linear construction of the book, and the subsequent narrative vom Auto aus by Felix Moeschlin.5 structure that connects time while the book is being read or a series of illustrations looked Both books provide a travel report at, makes it fundamentally better suited to explore the subject of movement than a single im- of a three-month tourist trip by age, coherent series of pictures are comparatively rare in the history of the illustrated book. car; two motorised, modern grand This discursive and narrative approach appears en passant, without being invested with any tours. -

“Showcasing 100 Years of German Architecture and Design”

PRESS RELEASE WHAT: 100 Years Deutscher Werkbund: Architecture and Design from Germany WHEN: April 04 to May 25, 2019 | Mondays to Saturdays | 10:00AM to 5:30PM WHERE: Metropolitan Museum of Manila “Showcasing 100 Years of German IN COOPERATION WITH: Architecture and Design” An exhibition introducing German architecture and design from the 20th century is coming to Manila this April 04 to May 25 at Metropolitan Museum of Manila. The exhibition entitled “100 Years Deutscher Werkbund“ is designed to mark the hundredth anniversary of the Deutscher Werkbund (DWB), a German association of artists, architects, designers, and industrialists, born out of a desire for greater efficiency in the crafts industry, better design for industry, and a more modern approach to architecture. It celebrates DWB‘s existence and describes their efforts, successes and achievements as one of the most important and influential SUPPORTED BY: institutions of the 20th century- an institution that helped to shape cultural life in other European countries as well. With posters, models, furniture, design, drawings and photos arranged chronologically in seven sections, the exhibit shows vividly the achievements of Deutscher Werkbund (DWB) throughtout the years as well as the question to the future of the group. All the key ideas, concepts and activities are grouped thematically and are related to larger political and social contexts. "100 Years Deutscher Werkbund" will open on April 04 with a program at Metropolitan Museum of Manila at 6pm. The designer of the exhibition, Beate Rosalia Schmidt from Germany, will be present at the opening program. It will be on display at the museum from April 04 to May 25, 2019, every Monday to Saturday at 10:00am to 5:30pm.