The Underside of Borders: Reading Chican@ and Native American Literature at the Turn of the Twenty-First Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

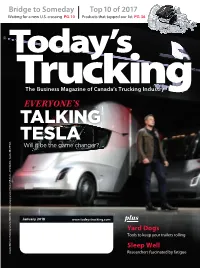

Talking Tesla Elon Musk

Bridge to Someday Top 10 of 2017 Waiting for a new U.S. crossing PG. 10 Products that topped our list PG. 36 The Business Magazine of Canada’s Trucking Industry EVERYONE’S TALKING TESLA W 5C4. Will it be the game changer? January 2018 www.todaystrucking.com plus Yard Dogs Tools to keep your trailers rolling Sleep Well Canadian Mail Sales Product Agreement #40063170. Return postage guaranteed. Newcom Media Inc., 451 Attwell Dr., Toronto, ON M9 Researchers fascinated by fatigue Contents January 2018 | VOLUME 32, NO.1 5 Letters 7 John G. Smith 10 16 9 Rolf Lockwood 31 Mike McCarron NEWS & NOTES Dispatches 13 MacKinnon Sold Ontario fleet sold to Contrans 22 Heard on the Street 32 36 23 Logbook 24 Truck Sales 25 Pulse Survey 26 Stat Pack 27 Trending 30 Truck of the Month In Gear 44 Yard Dogs Features Keep trailers moving in the yard with 10 Bridge to Someday specialized equipment Work on the Gordie Howe International 48 Southern Stars Bridge continues, but at a slow pace By Elizabeth Bate Cabovers gaining ground in Mexico 16 Talking Tesla 51 Product Watch Elon Musk (partially) unveils his electric truck. 52 Guess the location, Will it be the game changer he promises? By John G. Smith win a hat 32 Sleep Well Good health begins with proper sleep. Researchers want to know if drivers are getting what they need. By Elizabeth Bate 36 The Top 10 Here’s the tech that topped our editor’s list in 2017 By John G. Smith Cover Image: Courtesy of Tesla For more visit www.todaystrucking.com JANUARY 2018 3 BORN TO BE Designed with decades of experience BETTER. -

Addison Street Poetry Walk

THE ADDISON STREET ANTHOLOGY BERKELEY'S POETRY WALK EDITED BY ROBERT HASS AND JESSICA FISHER HEYDAY BOOKS BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA CONTENTS Acknowledgments xi Introduction I NORTH SIDE of ADDISON STREET, from SHATTUCK to MILVIA Untitled, Ohlone song 18 Untitled, Yana song 20 Untitied, anonymous Chinese immigrant 22 Copa de oro (The California Poppy), Ina Coolbrith 24 Triolet, Jack London 26 The Black Vulture, George Sterling 28 Carmel Point, Robinson Jeffers 30 Lovers, Witter Bynner 32 Drinking Alone with the Moon, Li Po, translated by Witter Bynner and Kiang Kang-hu 34 Time Out, Genevieve Taggard 36 Moment, Hildegarde Flanner 38 Andree Rexroth, Kenneth Rexroth 40 Summer, the Sacramento, Muriel Rukeyser 42 Reason, Josephine Miles 44 There Are Many Pathways to the Garden, Philip Lamantia 46 Winter Ploughing, William Everson 48 The Structure of Rime II, Robert Duncan 50 A Textbook of Poetry, 21, Jack Spicer 52 Cups #5, Robin Blaser 54 Pre-Teen Trot, Helen Adam , 56 A Strange New Cottage in Berkeley, Allen Ginsberg 58 The Plum Blossom Poem, Gary Snyder 60 Song, Michael McClure 62 Parachutes, My Love, Could Carry Us Higher, Barbara Guest 64 from Cold Mountain Poems, Han Shan, translated by Gary Snyder 66 Untitled, Larry Eigner 68 from Notebook, Denise Levertov 70 Untitied, Osip Mandelstam, translated by Robert Tracy 72 Dying In, Peter Dale Scott 74 The Night Piece, Thorn Gunn 76 from The Tempest, William Shakespeare 78 Prologue to Epicoene, Ben Jonson 80 from Our Town, Thornton Wilder 82 Epilogue to The Good Woman of Szechwan, Bertolt Brecht, translated by Eric Bentley 84 from For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide I When the Rainbow Is Enuf, Ntozake Shange 86 from Hydriotaphia, Tony Kushner 88 Spring Harvest of Snow Peas, Maxine Hong Kingston 90 Untitled, Sappho, translated by Jim Powell 92 The Child on the Shore, Ursula K. -

The Kindness of Strangers

THE KINDNESS OF STRANGERS 9780465064748-HCtext1P.indd 1 12/16/19 8:06 AM 9780465064748-HCtext1P.indd 2 12/16/19 8:06 AM THE KINDNESS OF STRANGERS HOW A SELFISH APE INVENTED A NEW MORAL CODE MICHAEL MCCULLOUGH New York 9780465064748-HCtext1P.indd 3 12/16/19 8:06 AM Copyright © 2020 by Michael McCullough Cover design by TK Cover image © TK Cover copyright © 2020 Hachette Book Group, Inc. Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture. The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights. Basic Books Hachette Book Group 1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104 www.basicbooks.com Printed in the United States of America First Edition: May 2020 Published by Basic Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Basic Books name and logo is a trademark of the Hachette Book Group. The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591. The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher. Print book interior design by Amy Quinn Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data has been applied for. -

The Lovely Serendipitous Experience of the Bookshop’: a Study of UK Bookselling Practices (1997-2014)

‘The Lovely Serendipitous Experience of the Bookshop’: A Study of UK Bookselling Practices (1997-2014). Scene from Black Books, ‘Elephants and Hens’, Series 3, Episode 2 Chantal Harding, S1399926 Book and Digital Media Studies Masters Thesis, University of Leiden Fleur Praal, MA & Prof. Dr. Adriaan van der Weel 28 July 2014 Word Count: 19,300 Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Chapter One: There is Value in the Model ......................................................................................................... 10 Chapter Two: Change and the Bookshop .......................................................................................................... 17 Chapter Three: From Standardised to Customised ....................................................................................... 28 Chapter Four: The Community and Convergence .......................................................................................... 44 Conclusion .................................................................................................................................................................... 51 Bibliography: ............................................................................................................................................................... 54 Archival and Primary Sources: ....................................................................................................................... -

The Images Speak for Themselves? Reading Refugee Coffee-Table Books

Visual Studies, Vol. 21, No. 1, April 2006 The images speak for themselves? Reading refugee coffee-table books ANNA SZO¨ RE´NYI The practice of collecting photographs of refugees in ‘coffee- consuming images. This article is concerned with the table books’ is a practice of framing and thus inflecting the implications of such texts and of the statements, such as meanings of those images. The ‘refugee coffee-table books’ Kumin’s, by which they are framed. What, indeed, are discussed here each approach their topic with a particular the effects of portraying refugees through photography? style and emphasis. Nonetheless, while some individual And in what sense can these effects be understood as images offer productive readings which challenge messages from refugees ‘themselves’? If these images stereotypes of refugees, the format of the collections and the speak, on whose behalf do they speak and what do they accompanying written text work to produce spectacle say? rather than empathy in that they implicitly propagate a According to the attitude expressed by Kumin, world view divided along imperialist lines, in which the photographs have an immediacy and intimacy that audience is expected to occupy the position of privileged engages the viewer. In the worldwide project of arousing viewing agent while refugees are positioned as viewed sympathy for refugees, such photographs seem to offer a objects. field for the development and expression of empathy. They draw on the tradition of socially concerned To suffer is one thing; another thing is living photography which has sought to provide a factual with the photographed images of suffering. -

Limited Editions Club

g g OAK KNOLL BOOKS www.oakknoll.com 310 Delaware Street, New Castle, DE 19720 Oak Knoll Books was founded in 1976 by Bob Fleck, a chemical engineer by training, who let his hobby get the best of him. Somehow, making oil refineries more efficient using mathematics and computers paled in comparison to the joy of handling books. Oak Knoll Press, the second part of the business, was established in 1978 as a logical extension of Oak Knoll Books. Today, Oak Knoll Books is a thriving company that maintains an inventory of about 25,000 titles. Our main specialties continue to be books about bibliography, book collecting, book design, book illustration, book selling, bookbinding, bookplates, children’s books, Delaware books, fine press books, forgery, graphic arts, libraries, literary criticism, marbling, papermaking, printing history, publishing, typography & type specimens, and writing & calligraphy — plus books about the history of all of these fields. Oak Knoll Books is a member of the International League of Antiquarian Booksellers (ILAB — about 2,000 dealers in 22 countries) and the Antiquarian Booksellers Association of America (ABAA — over 450 dealers in the US). Their logos appear on all of our antiquarian catalogues and web pages. These logos mean that we guarantee accurate descriptions and customer satisfaction. Our founder, Bob Fleck, has long been a proponent of the ethical principles embodied by ILAB & the ABAA. He has taken a leadership role in both organizations and is a past president of both the ABAA and ILAB. We are located in the historic colonial town of New Castle (founded 1651), next to the Delaware River and have an open shop for visitors. -

Universal Logistics Holdings, Inc

UNIVERSAL LOGISTICS HOLDINGS, INC. NOTICE OF 2020 ANNUAL MEETING OF SHAREHOLDERS PROXY STATEMENT AND 2019 ANNUAL REPORT UNIVERSAL LOGISTICS HOLDINGS, INC. 12755 E. Nine Mile Road Warren, Michigan 48089 (586) 920-0100 www.universallogistics.com NOTICE OF ANNUAL MEETING OF SHAREHOLDERS To Be Held on April 30, 2020 To our Shareholders: The 2020 annual meeting of shareholders of Universal Logistics Holdings, Inc., a Michigan corporation (“ULH” or the “Company”), will be held at 12755 E. Nine Mile Road, Warren, Michigan 48089, on April 30, 2020, at 10:00 a.m. local time. The meeting is being held for the purpose of considering and voting on the following proposals: 1. To elect ten directors to serve until the next annual meeting of shareholders and until their successors have been elected and qualified (the Board of Directors recommends a vote “FOR” the nominees named in the attached proxy statement proposal); 2. To conduct an advisory vote on the compensation of our named executive officers (the Board of Directors recommends a vote “FOR” this advisory proposal); 3. To ratify the appointment of BDO USA LLP as ULH’s independent registered public accounting firm for the next fiscal year (the Board of Directors recommends a vote “FOR” this proposal); 4. To conduct an advisory vote on a shareholder proposal for majority voting in uncontested director elections (the Board of Directors makes no recommendation regarding the vote on this advisory proposal); and 5. Such other business as may properly come before the meeting or any adjournment or postponement of the meeting. All shareholders of record as of the close of business on March 13, 2020, will be entitled to notice of and to vote at the meeting or any adjournment or postponement of the meeting. -

Native American Literature

ENGL 5220 Nicolas Witschi CRN 15378 Sprau 722 / 387-2604 Thursday 4:00 – 6:20 office hours: Wednesday 12:00 – 2:00 Brown 3002 . and by appointment e-mail: [email protected] Native American Literature Over the course of the last four decades or so, literature by indigenous writers has undergone a series of dramatic and always interesting changes. From assertions of sovereign identity and engagements with entrenched cultural stereotypes to interventions in academic and critical methodologies, the word-based art of novelists, dramatists, critics, and poets such as Sherman Alexie, Louise Erdrich, Louis Owens, N. Scott Momaday, Leslie Marmon Silko, Simon Ortiz, and Thomas King, among many others, has proven vital to our understanding of North American culture as a whole. In this course we will examine a cross-section of recent and exemplary texts from this wide-reaching literary movement, paying particular attention to the formal, thematic, and critical innovations being offered in response to questions of both personal and collective identity. This course will be conducted seminar-style, which means that everyone is expected to contribute significantly to discussion and analysis. TEXTS: The following texts are available at the WMU Bookstore: The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian, by Sherman Alexie (Spokane) The Last Report on the Miracles at Little No Horse, by Louise Erdrich (Anishinaabe) Bloodlines: Odyssey of a Native Daughter, by Janet Campbell Hale (Coeur d'Alene) The Light People, by Gordon D. Henry (Anishinaabe) Green Grass, Running Water, by Thomas King (Cherokee) House Made of Dawn, by N. Scott Momaday (Kiowa) from Sand Creek, by Simon Ortiz (Acoma) Nothing But The Truth, eds. -

Bridge Duel Continues Between State, Moroun

20090202-NEWS--0001-NAT-CCI-CD_-- 1/30/2009 6:04 PM Page 1 ® www.crainsdetroit.com Vol. 25, No. 5 FEBRUARY 2 – 8, 2009 $2 a copy; $59 a year ©Entire contents copyright 2009 by Crain Communications Inc. All rights reserved Inside State’s UI debt could Bridge duel continues mean higher taxes, Page 3 between state, Moroun Government gives nod for Rehab agency on the road both spans to fiscal recovery, NATHAN SKID/CRAIN’S DETROIT BUSINESS BY BILL SHEA Page 3 Christos Moisides (left) and Michael CRAIN’S DETROIT BUSINESS Sinanis of 23rd Street Studios have a studio site at 23rd and Michigan. The high-stakes standoff be- This Just In tween Manuel Moroun and an international coalition of gov- ernments continues as both Comerica economist: make incremental progress to- Recession is widening Motown ward competing billion-dollar Detroit River crossings. Dana Johnson, the chief The situation got fresh impe- economist for Comerica Bank, tus in recent weeks, thanks to a NATHAN SKID/CRAIN’S DETROIT BUSINESS said the current recession is movies pair of U.S. Department of Trans- Matthew Moroun, vice president of the Detroit International Bridge Co., stands in front of construction of the new bridge span, which will run next to the almost certain to become the portation approvals for the si- current bridge. longest since the 16-month multaneous bridge projects — downturns of 1973 and 1981, 2 groups shooting which include Michigan jointly four-lane structure. tion of infrastructure work on a which would make it the funding infrastructure at one Moroun’s Detroit International new highway interchange serving longest since the Great De- while seeking to build the other Bridge Co. -

EVIDENCE and INTERPRETATION in TWENTIETH-CENTURY INVESTIGATION NARRATIVES Erin Bartels Buller a Disse

THE UNLOCKED ROOM PROBLEM: EVIDENCE AND INTERPRETATION IN TWENTIETH-CENTURY INVESTIGATION NARRATIVES Erin Bartels Buller A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English and Comparative Literature. Chapel Hill 2013 Approved by: Minrose Gwin Linda Wagner-Martin Ruth Salvaggio John Marx Christopher Teuton ©2013 Erin Bartels Buller ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT ERIN BARTELS BULLER: The Unlocked Room Problem: Evidence and Interpretation in Twentieth-Century Investigation Narratives (Under the direction of Minrose Gwin) This project examines how a range of 20 th -century fictions and memoirs use tropes borrowed from detective fiction to understand the past. It considers the way the historiographical endeavor and the idea of evidence and interpretation are presented in William Faulkner’s Absalom, Absalom! , Go Down Moses, Intruder in the Dust , and the stories in Knight’s Gambit ; Robert Penn Warren’s All the King’s Men ; Louis Owens’s The Sharpest Sight and Bone Game ; and Lillian Hellman’s memoirs ( An Unfinished Woman, Pentimento, Scoundrel Time , and Maybe ). The historical novel and sometimes even memoir, in the 20 th century, often closely resembled the detective novel, and this project attempts to account for why. Long before Hayden White and other late 20 th - century theorists of historical practice demonstrated how much historical writing owes to narrative conventions, writers such as Faulkner and Warren had anticipated those scholars’ claims. By foregrounding the interpretation necessary to any historical narrative, these works suggest that the way investigators identify evidence and decide what it means is controlled by the rhetorical demands of the stories they are planning to tell about what has happened and by the prior loyalties and training of the investigators. -

Beauty Knows No Borders

Beauty Knows No Borders Banff National Park Alberta, Canada Beauty Knows No Borders Banff National Park Alberta, Canada Available Sizes: 16x20, 20x24, 30x40, 40x50, 50x62 Artist’s Choice: Della Terra, Charcoal with Black Linen Artist Proof: 50 / Limited Edition: 500 Beauty Knows No Borders Field Notes Banff National Park Alberta, Canada Camera: Arca Swiss 8x10 F-Line Camera Lens: 150mm This past summer I had the great pleasure of spending it entirely with my son. Aperture: f45.3 Toward the end of our time together we drove from our home in Oregon all the way Exposure: 1/4 Second up to Alaska on the Can-Am (Canadian-American) highway. After a week long back Film: Professional Fuji Astia 100f country stint in Denali I put him on the redeye flight home as school started the next morning. I wouldn’t trade our time together for anything - it was a blast. On the drive back home from Alaska I took my time going through Canada. I wasn’t in my home country anymore, I was the foreigner and I was about to have an epiphany. There are amazing nature sights to behold there - everywhere. The first snowfall of the season had just dusted the mountains. I starred in awe as the clouds parted and a beam of light touched the surface of this stunning mountain lake and illuminated the entire valley. Man’s pitiful attempt to place arbitrary lines upon the surface of the earth to retain what they believe to be ‘theirs’, and call them “borders”, yields because beauty knows nothing about that, beauty knows no borders. -

WLA Conference 2013 COVER

Mural of Queen Califia and her Amazons, Mark Hopkins Hotel in San Francisco – Maynard Dixon and Frank Von Sloun The name of California derives from the legend of Califia, the queen of an island inhabited by dark- skinned Amazons in a 1521 novel by Garci Ordóñez de Montalvo, Las Sergas de Esplandián. Califia has been depicted as the Spirit of California, and she often figures in the myth of California's origin, symbolizing an untamed and bountiful land prior to European settlement. California has been calling to the world ever since, as land of promise, dreams and abundance, but also often as a land of harsh reality. The 48th annual conference of the Western Literature Association welcomes you to Berkeley, California, on the marina looking out to the San Francisco Bay. This is a place as rich in history and myth as Queen Califia herself. GRATEFUL ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS go to the following sponsors for their generous support of the 2013 Western Literature Conference: • The Redd Center for Western Studies • American Studies, UC Berkeley • College of Arts & Humanities, UC Berkeley • English Department, UC Berkeley SPECIAL THANKS go to: • The Doubletree by Hilton Hotel • Aileen Calalo, PSAV Presentation Services • The Assistants to the President: Samantha Silver and George Thomas, Registration Directors; and Alaska Quilici, Hospitality and Event Coordinator • Sabine Barcatta, Director of Operations, Western Literature Association • William Handley, Executive Secretary / Treasurer, Western Literature Association • Paul Quilici, Program Graphic Designer • Sara Spurgeon, Kerry Fine, and Nancy Cook • Kathleen Moran • The ConfTool Staff Registration/ Info Table ATM EMC South - Sierra Nevada Islands Ballroom (2nd floor) (1st floor) Amador El Dorado Yerba Buena Belvedere Island Mariposa Treasure Island Angel Island Quarter Deck Islands Foyer Building (5) EMC North Conference Center (2nd floor) (3rd floor) (4th floor) Berkeley Sacramento Restrooms California Guest Pass for Wireless Access: available in the Islands Ballroom area and Building 5 1.