Review of the EQUIP-Tanzania School Readiness Programme

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To Read and Write with Understanding a Short Simple Sentence on Everyday Life

The United Republic of Tanzania The 2019 Baseline Survey on Socio-Economic Status of Persons with Albinism and Their Households in The Lake Zone Tanzania Albinism Society (TAS) and Karagwe Community Based Rehabilitation Programmes (KCBRP) December 2019 Table of Contents List of Tables ............................................................................................................... v List of Figures ............................................................................................................ xii List of Plates ........................................................................................................... xvi Abbreviations and Acronyms ................................................................................... xvii Acknowledgement ................................................................................................... xviii Executive Summary ................................................................................................... xix CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION ........................................................................ 1 1.1 Background .............................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Objective of the Survey ........................................................................................... 4 1.3 Survey Organization ................................................................................................ 5 1.3.1 Survey Design ...................................................................................................... -

A Case Study of Maswa and Bariadi Districts

The University of Dodoma University of Dodoma Institutional Repository http://repository.udom.ac.tz Humanities Master Dissertations 2013 Challenges of using English language in the Tanzanian Agricultural sector: a case study of Maswa and Bariadi districts Matalu, Kulwa The University of Dodoma Matalu, K. (2013). Challenges of using English language in the Tanzanian Agricultural sector: a case study of Maswa and Bariadi districts. Dodoma: The University of Dodoma. http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12661/1094 Downloaded from UDOM Institutional Repository at The University of Dodoma, an open access institutional repository. CHALLENGES OF USING ENGLISH LANGUAGE IN THE TANZANIAN AGRICULTURAL SECTOR CASE STUDY: MASWA AND BARIADI DISTRICTS Kulwa, Matalu A Dissertation Submitted in (Partial) Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Linguistics of the University of Dodoma. University Of Dodoma October, 2013 CERTIFICATION The undersigned certifies that she has read and hereby recommends for acceptance by the University of Dodoma a dissertation entitled Challenges of Using English Language in the Tanzanian Agricultural Sector; A Case of Maswa and Bariadi Districts in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Mater of Arts in Linguistics of the University of Dodoma. ……………………………………… Dr. Rafiki Yohana Sebonde (SUPERVISOR) Date…………………………….. i DECLARATION AND COPYRIGHT I, Kulwa Matalu, declare that this dissertation is my own original work and that it has not been presented and will not be presented to any other University for a similar or any other degree award. Signature …………………………………… No part of this dissertation may be reproduced, stored in any retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior written permission of the author or the University of Dodoma. -

TANZANIA OSAKA ALUMNI Best Practices Hand Book 5

TOA Best Practices Handbook 5 TANZANIA OSAKA ALUMNI Best Practices Hand Book 5 President’s Office, Regional Administration and Local Government, P.O. Box 1923, Dodoma. December, 2017 TOA Best Practices Handbook 5 BEST PRACTICES HAND BOOK 5 (2017) Prepared for Tanzania Osaka Alumni (TOA) by: Paulo Faty, Lecturer, Mzumbe University; Ahmed Nassoro, Assistant Lecturer, LGTI; Michiyuki Shimoda, Senior Advisor, PO-RALG Edited by Liana A. Hassan, TOA Vice Chairperson; Paulo Faty, Lecturer, Mzumbe University; Ahmed Nassoro, Assistant Lecturer, LGTI; Honorina Ng’omba, National Expert, JICA TOA Best Practices Handbook 5 Table of Contents Content Page List of Abbreviations i Foreword iii Preface (TOA) iv Preface (JICA) v CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION: LESSONS LEARNT FROM JAPANESE 1 EXPERIENCE CHAPTER TWO: SELF HELP EFFORTS FOR IMPROVED SERVICE 14 DELIVERY Mwanza CC: Participatory Water Hyacinth Control In Lake Victoria 16 Geita DC: Village Self Help Efforts For Improved Service Delivery 24 Chato DC: Community Based Establishment Of Satellite Schools 33 CHAPTER THREE: FISCAL DECENTRALIZATION AND REVENUE 41 ENHANCEMENT Bariadi DC: Revenue Enhancement for Improved Service delivery 42 CHAPTER FOUR: PARTICIPATORY SERVICE DELIVERY 50 Itilima DC: Community Based Environmental Conservation and Income 53 Generation Misungwi DC: Improving Livelihood and Education For Children With 62 Albinism Musoma DC: Promotion of Community Health Fund for Improved Health 70 Services Bukombe DC: Participatory Water Supply Scheme Management 77 Ngara DC: Participatory Road Opening -

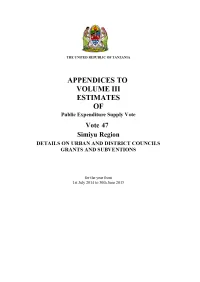

Council Subvote Index

Council Subvote Index 47 Simiyu Region Subvote Description Council District Councils Number Code 2036 Bariadi Town Council 5003 Internal Audit 5004 Admin and HRM 5005 Trade and Economy 5006 Administration and Adult Education 5007 Primary Education 5008 Secondary Education 5009 Land Development & Urban Planning 5010 Health Services 5011 Preventive Services 5012 Health Centres 5013 Dispensaries 5014 Works 5017 Rural Water Supply 5022 Natural Resources 5027 Community Development, Gender & Children 5031 Salaries for VEOs 5033 Agriculture 5034 Livestock 5036 Environments 3059 Maswa District Council 5003 Internal Audit 5004 Admin and HRM 5005 Trade and Economy 5006 Administration and Adult Education 5007 Primary Education 5008 Secondary Education 5009 Land Development & Urban Planning 5010 Health Services 5011 Preventive Services 5012 Health Centres 5013 Dispensaries 5014 Works 5017 Rural Water Supply 5022 Natural Resources 5027 Community Development, Gender & Children 5031 Salaries for VEOs 5033 Agriculture 5034 Livestock 5036 Environments 3060 Bariadi District Council 5003 Internal Audit 5004 Admin and HRM 5005 Trade and Economy 5006 Administration and Adult Education 5007 Primary Education 5008 Secondary Education 5009 Land Development & Urban Planning ii Council Subvote Index 47 Simiyu Region Subvote Description Council District Councils Number Code 3060 Bariadi District Council 5010 Health Services 5011 Preventive Services 5012 Health Centres 5013 Dispensaries 5014 Works 5017 Rural Water Supply 5022 Natural Resources 5027 Community Development, -

Climate Resilient Water Supply Project in Busega, Bariadi and Itilima Districts, Simiyu Region

THE UNITED REPUBLIC OF TANZANIA MINISTRY OF WATER AND IRRIGATION CLIMATE RESILIENT WATER SUPPLY PROJECT IN BUSEGA, BARIADI AND ITILIMA DISTRICTS, SIMIYU REGION RESETTLEMENT POLICY FRAMEWORK JANUARY 22 2017 Location: Busega, Bariadi and Itilima Districts, Simiyu Region Proponent: Ministry of Water and Irrigation, P.O. Box 9153, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania Consultant: Multiconsult ASA, Nedre Skøyen vei 2, N-0276 Oslo, Norway in association with NORPLAN Tanzania, Plot 92, Warioba Street, Miikocheni, Kinondoni, P.O.Box 2820, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania MINISTRY OF WATER AND IRRIGATION CLIMATE RESILIENT WATER SUPPLY PROJECT IN BUSEGA, BARIADI AND ITILIMA DISTRICTS, SIMIYU REGION RESETTLEMENT POLICY FRAMEWORK JANUARY 22 2017 LOCATION: Busega, Bariadi and Itilima Districts, Simiyu Region PROPONENT: Ministry of Water and Irrigation P.O. Box 9153, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania Tel: +255 22 2450836, Fax: +255 769 310271, E-mail: [email protected] CONSULTANT: Multiconsult ASA Nedre Skøyen vei 2, N-0276 Oslo, Norway Tel: +47 21585000, Fax: +47 21585001, E-mail: [email protected] in association with NORPLAN Tanzania Limited Plot 92, Warioba Street, Miikocheni, Kinondoni, P.O.Box 2820, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania Tel: +255 22 266 8090/ 6236/7020, Fax: +255 22 266 8340, E-mail: [email protected] Version: Final Report Date of issue: January 22, 2017 Prepared by: Multiconsult ASA in association with NORPLAN Tanzania Limited Checked by: Jørn Stave Approved by: Gro Dyrnes MINISTRY OF WATER AND IRRIGATION Climate Resilient Water Supply Project in Busega, Bariadi and Itilima Districts Resettlement Policy Framework January 22, 2017 | PAGE III TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction and BackGround .................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Project Background .............................................................................................................................. -

Health Facility Registry System Tools GPS and FRS Guideline 2014

United Republic Of Tanzania Ministry of Health and Social Welfare Health Facility Registry System User Manual for Master Facility List Data Collection Tool, Global Positioning System and Facility Registry Software February 2014 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This manual was developed in collaboration with various institutions and organization. We thank them all for their contribution: Ministry of Health and Social Welfare National Institute for Medical Research RTI International Table of Contents Abbreviations ........................................................................................................................................... i Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 1 Definition of terms .................................................................................................................................. 2 Part I: Data Collection Tool Guide ............................................................................................................ 3 1. Administrative Divisions: .............................................................................................................. 3 2. Identification ............................................................................................................................... 3 3. Contact Information ..................................................................................................................... 3 4. Physical Location......................................................................................................................... -

Appendices to Vol 4B

Vote 47 Simiyu Region Councils in the Region Council District Councils Code 2036 Bariadi Town Council 3059 Maswa District Council 3060 Bariadi District Council 3082 Meatu District Council 3116 Busega District Council 3139 Itilima District Council 2 Vote 47 Simiyu Region Council Development Budget Summary Local and Foreign 2014/15 Code Council Local Foreign Total 2036 Bariadi Town Council 3,161,287,000 3,038,797,000 6,200,084,000 3059 Maswa District Council 3,191,688,000 1,703,956,000 4,895,644,000 3060 Bariadi District Council 2,967,216,000 2,444,370,000 5,411,586,000 3082 Meatu District Council 4,631,747,000 1,776,205,000 6,407,952,000 3116 Busega District Council 3,515,463,000 1,902,436,000 5,417,899,000 3139 Itilima District Council 3,875,644,000 1,557,441,000 5,433,085,000 Total 21,343,045,000 12,423,205,000 33,766,250,000 3 Vote 47 Simiyu Region Code Description 2012/2013 2013/2014 2014/2015 Actual Expenditure Approved Expenditure Estimates Local Foreign Local Foreign Local Foreign Total Shs. Shs. Shs. 47 Simiyu Region 3280 Rural Water Supply & Sanitation 0 0 0 2,182,194,000 0 2,374,515,000 2,374,515,000 4390 Secondary Education Development 0 0 0 1,103,994,000 0 1,901,076,000 1,901,076,000 Programme 4404 District Agriculture Development Support 0 0 0 2,536,239,000 0 0 0 4486 Agriculture Sector Dev. Prog. Support 0 0 0 330,000,000 0 1,247,000,000 1,247,000,000 4553 Livestock Development Fund 0 0 20,830,000 0 0 0 0 4946 LGA's Own Sources Project 0 0 0 0 7,499,335,000 0 7,499,335,000 5421 Health Sector Prog. -

2012 Population and Housing Census

The United Republic of Tanzania 2012 POPULATION AND HOUSING CENSUS Population Distribution by Administrative Areas National Bureau of Statistics Ministry of Finance Dar es Salaam and Office of Chief Government Statistician President’s Office, Finance, Economy and Development Planning Zanzibar March , 2013 Foreword The 2012 Population and Housing Census (PHC) for United Republic of Tanzania was carried out on the 26th August, 2012. This was the fifth Census after the Union of Tanganyika and Zanzibar in 1964. Other Censuses were carried out in 1967, 1978, 1988 and 2002. The 2012 PHC, like others, will contribute to the improvement of quality of life of Tanzanians through the provision of current and reliable data for development planning, policy formulation and services delivery as well as for monitoring and evaluating national and international development frameworks. The 2012 PHC is unique in the sense that, the information collected will be used in monitoring and evaluating the Development Vision 2025 for Tanzania Mainland and Zanzibar Development Vision 2020, Five Year Development Plan 2011/12 – 2015/16, National Strategy for Growth and Reduction of Poverty (NSGRP) commonly known as MKUKUTA and Zanzibar Strategy for Growth and Reduction of Poverty (ZSGRP) commonly known as MKUZA. The census will also provide information for the evaluation of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) in 2015. The Poverty Monitoring Master Plan, which is the monitoring tool for NSGRP and ZSGRP, mapped out core indicators for poverty monitoring against the sequence of surveys, with the 2012 Census being one of them. Several of these core indicators for poverty monitoring will be measured directly from the 2012 Census. -

Invitation for Tenders

THE UNITED REPUBLIC OF TANZANIA PRESIDENT’S OFFICE TANZANIA RURAL AND URBAN ROADS AGENCY (TARURA) SIMIYU REGION TENDERS FOR ROUTINE/RECURRENT MAINTENANCE, PERIODIC MAINTENANCE, SPOT IMPROVEMENT, BRIDGE REPAIR AND INSTALLATION OF CULVERTS ON VARIOUS RURAL AND URBAN ROADS IN SIMIYU REGION. INVITATION FOR TENDERS Date: 08th July, 2019 1.This invitation for tenders follows the General Procurement Notice for these projects which appeared in the PPRA tender portal Issue number 1821 of dated 07th June, 2019. 2. The Government of the United Republic of Tanzania has set aside fund for the operation of the Tanzania Rural and Urban Roads Agency (TARURA) Simiyu Region Office, in the Financial Year 2019/2020 for Routine/Recurrent Maintenance, Periodic Maintenance, Spot Improvement, bridge repair and Installation of Culverts on various Rural and Urban Roads within the Region. It is intended that part of the proceeds of the fund will be used to cover eligible payments under the contracts for advertised road works. 3. The Regional Coordinator TARURA Simiyu on behalf of the Chief Executive Officer TARURA, now invites sealed tenders from eligible National Civil engineering contractors and Special groups (Youth, Women, Elders and Disabled) registered with the Contractors Registration Board (CRB) of Tanzania as shown in the table below with the indicated approximate quantities of major BOQ items. S/N Description Tender No. Approximate Qty of major scope of the works Eligible contractors Site visit date Council • Light grading – 7km Routine Maintenance along -

Bariadi District Council Strategic Planning Process and Activities

STRATEGIC PLAN 2013/2014 – 2017/2018 Bariadi District Council UNITED REPUBLIC OF TANZANA PRIME MINISTER’S OFFICE REGIONAL ADMINISTRATION AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT BARIADI DISTRICT COUNCIL STRATEGIC PLAN (2013/2014 - 2017/2018) District Executive Director’s Office, Bariadi District Council, P.O. Box 102, BARIADI - TANZANIA. 1 STRATEGIC PLAN 2013/2014 – 2017/2018 Bariadi District Council TABLE OF CONTENTS Contents Page CHAPTER ONE .......................................................................................................................................... 4 BACKGROUND INFORMATION OF THE DISTRICT ................................................................. 4 1.1 Location .......................................................................................................................................... 4 1.2 Land area ........................................................................................................................................ 4 1.3 Population size and Growth ........................................................................................................ 4 1.4 Administration Units .................................................................................................................... 5 1.5 Administratively............................................................................................................................. 5 1.6 The District Council has 6 standing Committees namely ....................................................... 5 CHAPTER TWO ......................................................................................................................................... -

African Postal Heritage; African Studies Centre Leiden; APH Paper 19, Part 1; Ton Dietz Tanzania Postmarks: Northern Tanzania; Version May 2017

African Postal Heritage; African Studies Centre Leiden; APH Paper 19, Part 1; Ton Dietz Tanzania Postmarks: Northern Tanzania; Version May 2017 African Studies Centre Leiden African Postal Heritage APH Paper nr 19, part 1 Ton Dietz Tanzania Postmarks: Northern Tanzania Version May 2017 Introduction Postage stamps and related objects are miniature communication tools, and they tell a story about cultural and political identities and about artistic forms of identity expressions. They are part of the world’s material heritage, and part of history. Ever more of this postal heritage becomes available online, published by stamp collectors’ organizations, auction houses, commercial stamp shops, online catalogues, and individual collectors. Virtually collecting postage stamps and postal history has recently become a possibility. These working papers about Africa are examples of what can be done. But they are work-in- progress! Everyone who would like to contribute, by sending corrections, additions, and new area studies can do so by sending an email message to the APH editor: Ton Dietz ([email protected]). You are welcome! Disclaimer: illustrations and some texts are copied from internet sources that are publicly available. All sources have been mentioned. If there are claims about the copy rights of these sources, please send an email to [email protected], and, if requested, those illustrations will be removed from the next version of the working paper concerned. 1 African Postal Heritage; African Studies Centre Leiden; APH Paper -

Food Security & Large-Scale Land Acquisitions: the Cases of Tanzania and Ethiopia

Food security and large-scale land acquisitions: The cases of Tanzania and Ethiopia A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Political Science of the McMicken College of Arts and Sciences by Jennifer Dye M.A. Political Science, University of Cincinnati, 2010 J.D. University of Cincinnati College of Law, 2010 March 2014 Committee Chair: Laura Jenkins, Ph.D. Abstract Food security is often misunderstood: overlooked in security studies and essentialized as a biological and nutritional issue, or as simply supply not matching demand. Yet, food security rests on underlying social and political questions of power, entitlement, distribution, and access within the food system and land tenure. This dissertation seeks to unearth these underlying social and political questions by examining how external large-scale land acquisitions affect food security and land tenure in the developing African state. This dissertation argues that external large-scale land acquisitions have a primarily negative impact on both food security and land tenure. Findings from the cases of Tanzania and Ethiopia show that large-scale land acquisitions maintain a system of social, political, and economic entitlements that foster uneven structures that result in low levels of food security and access to land. i ii Dedicated to Floyd and my parents iii Acknowledgements During my time in graduate school, I have received support and encouragement from a great number of individuals from various departments, colleges, and in my personal life. Thank you to all who have helped me as I worked on my dissertation.