Discourses of Heterosexual Female Masochism and Submission from the 1880S to the Present Day

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wignall, Liam (2018) Kinky Sexual Subcultures and Virtual Leisure Spaces. Doctoral Thesis, University of Sunderland

Wignall, Liam (2018) Kinky Sexual Subcultures and Virtual Leisure Spaces. Doctoral thesis, University of Sunderland. Downloaded from: http://sure.sunderland.ac.uk/id/eprint/8825/ Usage guidelines Please refer to the usage guidelines at http://sure.sunderland.ac.uk/policies.html or alternatively contact [email protected]. Kinky Sexual Subcultures and Virtual Leisure Spaces Liam Wignall A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Sunderland for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy February 2018 i | P a g e Abstract This study seeks to understand what kink is, exploring this question using narratives and experiences of gay and bisexual men who engage in kink in the UK. In doing so, contemporary understandings of the gay kinky subcultures in the UK are provided. It discusses the role of the internet for these subcultures, highlighting the use of socio-sexual networking sites. It also recognises the existence of kink dabblers who engage in kink activities, but do not immerse themselves in kink communities. A qualitative analysis is used consisting of semi-structured in-depth interviews with 15 individuals who identify as part of a kink subculture and 15 individuals who do not. Participants were recruited through a mixture of kinky and non-kinky socio-sexual networking sites across the UK. Complimenting this, the author attended kink events throughout the UK and conducted participant observations. The study draws on subcultural theory, the leisure perspective and social constructionism to conceptualise how kink is practiced and understood by the participants. It is one of the first to address the gap in the knowledge of individuals who practice kink activities but who do so as a form of casual leisure, akin to other hobbies, as well as giving due attention to the increasing presence and importance of socio-sexual networking sites and the Internet more broadly for kink subcultures. -

THE LAST SEX: FEMINISM and OUTLAW BODIES 1 Arthur and Marilouise Kroker

The Last Sex feminism and outlaw bodies CultureTexts Arthur and Marilouise Kroker General Editors CultureTexts is a series of creative explorations of the theory, politics and culture of postmodem society. Thematically focussed around kky theoreti- cal debates in areas ranging from feminism and technology to,social and political thought CultureTexts books represent the forward breaking-edge of contempory theory and prac:tice. Titles The Last Sex: Feminism and Outlnw Bodies edited and introduced by Arthur and Marilouise Kroker Spasm: Virtual Reality, Android Music and Electric Flesh Arthur Kroker Seduction Jean Baudrillard Death cE.tthe Parasite Cafe Stephen Pfohl The Possessed Individual: Technology and the French Postmodern Arthur Kroker The Postmodern Scene: Excremental Culture and Hyper-Aesthetics Arthur Kroker and David Cook The Hysterical Mule: New Feminist Theory edited and introduced by Arthur-and Marilouise Kroker Ideology and Power in the Age of Lenin in Ruins edited and introduced by Arthur and Marilouise Kroker , Panic Encyclopedia Arthur Kroker, Maril.ouise Kroker and David Cook Life After Postmodernism: Essays on Value and Culture edited and intloduced by John Fekete Body Invaders edited and introduced by Arthur and Marilouise Kroker THE LAST SEX feminism and outlaw bodies Edited with an introduction by Arthur and Marilouise Kroker New World Perspectives CultureTexts Series Mont&al @ Copyright 1993 New World Perspectives CultureTexts Series All rights reserved. No part of this publication may he reproduced, stored in o retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without prior permission of New World Perspectives. New World Perspectives 3652 Avenue Lava1 Montreal, Canada H2X 3C9 ISBN O-920393-37-3 Published simultaneously in the U.S.A. -

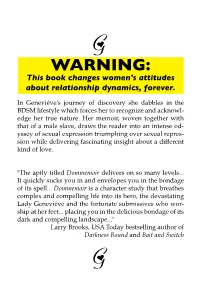

WARNING: This Book Changes Women's Attitudes About Relationship Dynamics, Forever

G WARNING: This book changes women's attitudes about relationship dynamics, forever. In Geneviéve's journey of discovery she dabbles in the BDSM lifestyle which forces her to recognize and acknowl- edge her true nature. Her memoir, woven together with that of a male slave, draws the reader into an intense od- yssey of sexual expression triumphing over sexual repres- sion while delivering fascinating insight about a different kind of love. "The aptly titled Dommemoir delivers on so many levels... It quickly sucks you in and envelopes you in the bondage of its spell... Dommemoir is a character study that breathes complex and compelling life into its hero, the devastating Lady Geneviéve and the fortunate submissives who wor- ship at her feet... placing you in the delicious bondage of its dark and compelling landscape..." Larry Brooks, USA Today bestselling author of Darkness Bound and Bait and Switch G Dommemoir by the Lady Geneviéve et al as told to I.G. Frederick Second Electronic Edition ISBN: 978-1-937471-94-1 © 2012 by I.G. Frederick First published in the U.S.A. 2009 All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permis- sion in writing from the author, except by reviewers who may quote brief excerpts in connection with a review. This book is a work of fiction. The names, characters, places, and incidents are products of the writer’s imagination or have been used fictitiously and are not to be construed as real. -

Kinky Checklist

Sex Gets Real invites you to... Get Your Kinky On Ready to explore some edgy, kinky play in the bedroom? This comprehensive checklist is the perfect way for you and your lover to discover fantasies you may have in common, and to help launch a more open discussion about desires and needs. Remember - our limits and desires change over time. Use this periodically to check in and try new things! Time to get sexy... sexgetsreal.com Copyright 2016, Sex Gets Real, LLC Welcome to your kinky, juicy checklist of fun. Before we begin, let's go over a few tips and guidelines to ensure you get exactly what you want out of this list. 1. Different strokes for different folks. What follows is a collection of sweet, intimate, edgy, invasive, loving, violent, and dangerous types of play. Keep an open mind, but never do anything you aren't ready to explore. 2. Do it alone, or with others. Use this list to check in with yourself. What interests you? What scares you, but sets your body on fire? Or, make a few copies, and have your lover complete one, as well. Compare notes, and see what you may have in common. 3. You determine the intensity. Honor your body. Respect your limits. This is not about harming yourself or others. This is about having fun and making sex into an adventure. If you see something like biting or flogging or hair pulling, those things can be done so lightly they almost tickle. Rape play sounds scary, but what if it's just you blindfolded and your lover wearing new cologne so they smell like a stranger? Get creative. -

Curing Sexual Deviance : Medical Approaches to Sexual Offenders in England, 1919-1959

ORBIT - Online Repository of Birkbeck Institutional Theses Enabling Open Access to Birkbecks Research Degree output Curing sexual deviance : medical approaches to sexual offenders in England, 1919-1959 http://bbktheses.da.ulcc.ac.uk/188/ Version: Full Version Citation: Weston, Janet (2016) Curing sexual deviance : medical approaches to sexual offenders in England, 1919-1959. PhD thesis, Birkbeck, University of Lon- don. c 2016 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copyright law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit guide Contact: email Curing sexual deviance Medical approaches to sexual offenders in England, 1919-1959 Janet Weston Department of History, Classics, and Archaeology Birkbeck, University of London Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2015 1 Declaration: I confirm that all material presented in this thesis is my own work, except where otherwise indicated. Signed ............................................... 2 Abstract This thesis examines medical approaches to sexual offenders in England between 1919 and 1959. It explores how doctors conceptualised sexual crimes and those who committed them, and how these ideas were implemented in medical and legal settings. It uses medical and criminological texts alongside information about specific court proceedings and offenders' lives to set out two overarching arguments. Firstly, it contends that sexual crime, and the sexual offender, are useful categories for analysis. Examining the medical theories that were put forward about the 'sexual offender', broadly defined, and the ways in which such theories were used, reveals important features of medico-legal thought and practice in relation to sexuality, crime, and 'normal' or healthy behaviour. -

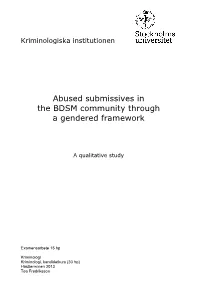

Abused Submissives in the BDSM Community Through a Gendered Framework

Kriminologiska institutionen Abused submissives in the BDSM community through a gendered framework A qualitative study Examensarbete 15 hp Kriminologi Kriminologi, kandidatkurs (30 hp) Höstterminen 2013 Tea Fredriksson Summary This study examines how abuse is viewed and talked about in the BDSM community. Particular attention is paid to gender actions and how a gendered framework of masculinities and femininities can further the understanding of how abuse is discussed within the community. The study aims to explore how sexual abuse of submissive men is viewed and discussed within the BDSM community, as compared to that of women. The study furthermore focuses on heterosexual contexts, with submissive men as victims of female perpetrators as its primary focus. To my knowledge, victimological research dealing with the BDSM community and its own views and definitions of abuse has not been conducted prior to the present study. Thus, the study is based on previous research into consent within BDSM, as this research provides a framework for non-consent as well. To conduct this study I have interviewed six BDSM practitioners. Their transcribed stories were then subjected to narrative analysis. The analysis of the material shows that victim blaming tendencies exist in the community, and that these vary depending on the victim’s gender. The findings indicate that the community is prone to victim blaming, and that this manifests itself differently for men and women. Furthermore, my results show that male rape myths can be used to understand cool victim-type explanations given by male victims of abuse perpetrated by women. After discussing my results, I suggest possible directions for further research. -

Man Enough: Fraternal Intimacy, White Homoeroticism, and Imagined Homogeneity in Mid-Nineteen

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: MAN ENOUGH: FRATERNAL INTIMACY, WHITE HOMOEROTICISM, AND IMAGINED HOMOGENEITY IN MID-NINETEENTH-CENTURY AMERICAN LITERATURE Geoffrey Saunders Schramm, Doctor of Philosophy, 2006 Dissertation directed by: Professor Marilee Lindemann Department of English “Man Enough” construes mid-nineteenth-century literary representations of sameness as corollaries of the struggle during this volatile era to realize unity among white men. I argue that three canonical authors envision homoerotic or same-sex erotic desire as a mechanism through which men can honor and defend sameness. These authors advert the connotative power of sameness by envisioning or assaying erotic desire between men as democratic. This fraternally conjugal (or conjugally fraternal) union serves as a consequence of the cultural directive to preserve the nation’s homogeneity. In chapter one I reflect upon the circulation of sameness in mid-nineteenth- century America. I provide an overview of the logic of sameness in conceptions of race and then discuss how it textured sexual difference. As historians have recorded, new homosocial spheres led to fraternal intimacy at a time when white men competed in the free market economy. These new forms of friendship were erotically—though not necessarily sexually—charged. In the second chapter I argue that in The Blithedale Romance Hawthorne represents homoeroticism as effecting strong, yet tender erotic bonds between men that circumvent women and feminizing domesticity. He ultimately registers that same-sex erotic desire imperils male individualism and autonomy since it demands submission. Chapter three begins with an observation that critics fail to consider how dominant attitudes about race and gender shaped Whitman’s representations. -

XRU-BDSM-Glossary

BDSM Glossary A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | V | W | X A Age play - A type of role play to gratify a fetish surrounding age; typically daddy/child or mommy/child fantasies [see: Infantilism]. Algolagnic - The act of transforming pain into sexual pleasure. A synonym for sadomasochism. [see: Sadism, Sadist; Sadomasochism; Masochism, Masochist]. Alternative sexuality - A sexual orientation that differs from a preference for vaginal inter- course (with minor variations) within a monogamous heterosexual relationship. Alternative lifestyle - Having a sexuality that differs significantly from the “norm” (see: Alter- native sexuality) may make an alternative lifestyle necessary or desirable. A sexual orienta- tion less common than the norm may stigmatize the individual pushing the person to seek a more accepting subculture. An example is homosexuality and the formation of the gay community. Anal play - Any sexual or fetish practice concerning the anus and/or rectum, chiefly includes: anal sex, rimming, enema play, and anal fisting. Anal training - Preparation of the anus for anal play. Anilingus - Anal-oral sex. Dental dam or plastic wrap is helpful for preventing exchange of harmful organisms. Animal play - Role playing wherein one or both partners assumes the role of an animal, chiefly: puppy, dog, and pony. Asphyxiation play - Restricting air (and/or blood) flow by choking to enhance the sensation of orgasm. B BDSM - Bondage and Discipline (BD), Dominance and Submission (DS) and Sadomasochism (SM). Black lightning - A common nickname for a black fiber glass or resin rod that is used as a cane. -

List of Paraphilias

List of paraphilias Paraphilias are sexual interests in objects, situations, or individuals that are atypical. The American Psychiatric Association, in its Paraphilia Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, Fifth Edition (DSM), draws a Specialty Psychiatry distinction between paraphilias (which it describes as atypical sexual interests) and paraphilic disorders (which additionally require the experience of distress or impairment in functioning).[1][2] Some paraphilias have more than one term to describe them, and some terms overlap with others. Paraphilias without DSM codes listed come under DSM 302.9, "Paraphilia NOS (Not Otherwise Specified)". In his 2008 book on sexual pathologies, Anil Aggrawal compiled a list of 547 terms describing paraphilic sexual interests. He cautioned, however, that "not all these paraphilias have necessarily been seen in clinical setups. This may not be because they do not exist, but because they are so innocuous they are never brought to the notice of clinicians or dismissed by them. Like allergies, sexual arousal may occur from anything under the sun, including the sun."[3] Most of the following names for paraphilias, constructed in the nineteenth and especially twentieth centuries from Greek and Latin roots (see List of medical roots, suffixes and prefixes), are used in medical contexts only. Contents A · B · C · D · E · F · G · H · I · J · K · L · M · N · O · P · Q · R · S · T · U · V · W · X · Y · Z Paraphilias A Paraphilia Focus of erotic interest Abasiophilia People with impaired mobility[4] Acrotomophilia -

2018 Juvenile Law Cover Pages.Pub

2018 JUVENILE LAW SEMINAR Juvenile Psychological and Risk Assessments: Common Themes in Juvenile Psychology THURSDAY MARCH 8, 2018 PRESENTED BY: TIME: 10:20 ‐ 11:30 a.m. Dr. Ed Connor Connor and Associates 34 Erlanger Road Erlanger, KY 41018 Phone: 859-341-5782 Oppositional Defiant Disorder Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Conduct Disorder Substance Abuse Disorders Disruptive Impulse Control Disorder Mood Disorders Research has found that screen exposure increases the probability of ADHD Several peer reviewed studies have linked internet usage to increased anxiety and depression Some of the most shocking research is that some kids can get psychotic like symptoms from gaming wherein the game blurs reality for the player Teenage shooters? Mylenation- Not yet complete in the frontal cortex, which compromises executive functioning thus inhibiting impulse control and rational thought Technology may stagnate frontal cortex development Delayed versus Instant Gratification Frustration Tolerance Several brain imaging studies have shown gray matter shrinkage or loss of tissue Gray Matter is defined by volume for Merriam-Webster as: neural tissue especially of the Internet/gam brain and spinal cord that contains nerve-cell bodies as ing addicts. well as nerve fibers and has a brownish-gray color During his ten years of clinical research Dr. Kardaras discovered while working with teenagers that they had found a new form of escape…a new drug so to speak…in immersive screens. For these kids the seductive and addictive pull of the screen has a stronger gravitational pull than real life experiences. (Excerpt from Dr. Kadaras book titled Glow Kids published August 2016) The fight or flight response in nature is brief because when the dog starts to chase you your heart races and your adrenaline surges…but as soon as the threat is gone your adrenaline levels decrease and your heart slows down. -

Scene Questionnaire

Scene Questionnaire The following is a list of activities in the BDSM scene. It can be used by both the dominant (male or female) and the Submissive (female) to interview each other, and see what level both are at. It is also used to find commonality. Place a check next to each box which you can relate to the most. If confused, go to the next one, and come back when finished with the rest. Answer each question honestly. Where it says "Yes/No/Try" = means whether you've experienced that type of activity before. Put "Y" for yes or "N" for no and a “T” to try something new. Rating scale for checklist: 0 = Do not ever ask me to do this, or hard limit. 1 = I don't want to do this activity, but wouldn't object if it was asked of me. 2 = I'm willing to do this activity, but it has no real appeal for me. 3 = I usually like doing this activity, at least on an occasional basis. 4 = I love doing this activity, and would like to experience it on a regular basis. 5 = I love this activity it makes me "hot", and would like it as often as possible. Note1. Some of these may fall under a few categories (example: Blindfolds can be Humiliation & mental bondage) Note2. Some of these could be used for health reasons too (example forced exercising) CORPORAL PUNISHMENT Y/N/T # Activity Belts Bruises Cane (leather) Cane (plastic) Cat (braided) Cat (no knots) Crop Flogger Leather Paddle Paddle Spanking Whip Wooden Hair Brush Wooden Paddle ROLE PLAY Y/N/T # Activity Act as objects (cars, furniture, etc) Arrested Baby Burglar Attack Call Girl Cowgirl Interrogation -

Degenerate Germany

0) 'CO :; lYde MAOALLS DEGENERATE GERMANY DEGENERATE GERMANY DEDICATED TO THOSE FEW, YET TOO MANY BRITONS WHO STILL HARBOUR Till- M/srlllLTo/ s ILLUSION THAT THE GERMANS ARE AN ESTIMABLE, PEACEFUL AND KINDLY PEOPLE, UTTERLY MIX/.LI* AND MISREPRESENTED BY THEIR WICKED ' 'l//,\- MBNT. DEGENERATE GERMANY BY HENRY DE HALSALLE av a Tror (Lysi.ie Oratioaes. TWENTIETH THOUSAND. PUBLISHED AT 8, ESSEX STREET, STRAND, BY T. WERNER LAURIE, LTD. Us AUTHOR'S PREFACE IT is to be feared that of the facts set forth in this volume " many " are of a distinctly unpleasant nature, so unpleasant that the writer would fain have omitted them. But had he done so he would have failed to substantiate his case i.e., that the German people are undeniably a degenerate race, if not the most degenerate race in Europe. Moreover, the writer contends that these un- wholesome facts (taken largely from German sources), nauseous as they may be, demand to be placed on record in a British publica- tion. Further, he believes such facts cannot be too widely known, and that their knowledge will be of value in combating the pre- " " posterous and dangerous peace ideas unfortunately held in various quarters in Great Britain : For instance, among those ill-informed, emasculated individuals styling themselves the " Union of Democratic Control." Also the writer would commend a perusal of the statistics in reference to German vice and crime contained herein to those of our politicians (and they are many) totally with the mental and moral condition of the unacquainted " " German people. Recognizing the adult character of many of the statements and facts recorded in this book the writer thought it best to obtain responsible opinion as to whether such statements and facts should be made public, and he therefore approached Mr.