Siachen: a By-Product of the Kashmir Dispute and a Catalyst for Its Resolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

India-Pakistan Conflict: Records of the Us State Department, February 1963

http://gdc.gale.com/archivesunbound/ INDIA-PAKISTAN CONFLICT: RECORDS OF THE U.S. STATE DEPARTMENT, FEBRUARY 1963-1966 Over 16,000 pages of State Department Central Files on India and Pakistan from 1963 through 1966 make this collection a standard documentary resource for the study of the political relations between India and Pakistan during a crucial period in the Cold War and the shifting alliances and alignments in South Asia. Date Range: 1963-1966 Content: 15,387 images Source Library: U.S. National Archives Detailed Description: Relations with Pakistan have demanded a high proportion of India’s international energies and undoubtedly will continue to do so. India and Pakistan have divergent national ideologies and have been unable to establish a mutually acceptable power equation in South Asia. The national ideologies of pluralism, democracy, and secularism for India and of Islam for Pakistan grew out of the pre-independence struggle between the Congress and the All-India Muslim League, and in the early 1990s the line between domestic and foreign politics in India’s relations with Pakistan remained blurred. Because great-power competition—between the United States and the Soviet Union and between the Soviet Union and China—became intertwined with the conflicts between India and Pakistan, India was unable to attain its goal of insulating South Asia from global rivalries. This superpower involvement enabled Pakistan to use external force in the face of India’s superior endowments of population and resources. The most difficult problem in relations between India and Pakistan since partition in August 1947 has been their dispute over Kashmir. -

The Constitutional Status of Gilgit Baltistan: Factors and Implications

The Constitutional Status of Gilgit Baltistan: Factors and Implications By Name: Syeda Batool National University of Modern Languages, Islamabad April 2019 1 The Constitutional Status of Gilgit Baltistan: Factors and Implications by Name: Syeda Batool M.Phil Pakistan Studies, National University of Modern Languages, 2019 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY in PAKISTAN STUDIES To FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES, DEPARTMENT OF PAKISTAN STUDIES National University of Modern Languages, Islamabad April 2019 @Syeda Batool, April 2019 2 NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF MODERN LANGUAGES FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES THESIS/DISSERTATION AND DEFENSE APPROVAL FORM The undersigned certify that they have read the following thesis, examined the defense, are satisfied with the overall exam performance, and recommend the thesis to the Faculty of Social Sciences for acceptance: Thesis/ Dissertation Title: The Constitutional Status of Gilgit Baltistan: Factors and Implications Submitted By: Syed Batool Registration #: 1095-Mphil/PS/F15 Name of Student Master of Philosophy in Pakistan Studies Degree Name in Full (e.g Master of Philosophy, Doctor of Philosophy) Degree Name in Full Pakistan Studies Name of Discipline Dr. Fazal Rabbi ______________________________ Name of Research Supervisor Signature of Research Supervisor Prof. Dr. Shahid Siddiqui ______________________________ Signature of Dean (FSS) Name of Dean (FSS) Brig Muhammad Ibrahim ______________________________ Name of Director General Signature of -

Download Deployment Map.Pdf

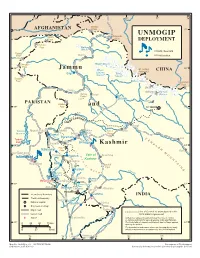

73o 74o 75o 76o 77o 78o Mintaka 37o AFGHANISTAN Pass 37o --- - UNMOGIP Darkot Khunjerab Pass Pass DEPLOYMENT - Thui- An Pass Batura- Glacier UN HQ / Rear HQ Chumar Khan- Baltit UN field station Pass Shandur- Hispar Glacier Pass 36o 36o Jammu Chogo Mt. Godwin CHINA Lungma Austin (K2) Gilgit Biafo 8611m Glacier Glacier Dadarili Baltoro Glacier Pass Karakoram Pass Sia La - Chilas Bilafond La Siachen Nanga Astor Glacier Parbat -- 8126m Skardu PAKISTAN Goma Babusar-- 35o Pass and 35o NJ 980420 X Kel ONTR C O F L LINE O - s a r Kargil D Tarbela Muzaffarabad- Tithwal- Wular Zoji La Dras- Reservoir Sopur Lake Pass Domel J h Jhe ---- e am Baramulla a m Z - Leh Tarbela A Dam Uri Srinagar- N Chakothi Kashmir S o o 34 K - 34 Haji-- Pir A - R Rawalakot Pass P - - - i- Karu Campbellpore Islamabad r M - O Titrinot P Vale of Anantnag Islamabad--- Poonch U a Kashmir N Mendhar n T Rawalpindi- Kotli j - A a- Banihal I ch l Pass N - n u R S P Rajouri C a n hen - Mangla g e ab Reservoir Naushahra- - Mangla Dam New Mirpur- Riasi 33o Munawwarwali- 33o - Jhelum Tawi Bhimber Chhamb Udhampur Akhnur- NW 605550 X International boundary Jammu INDIA - b Provincial boundary - na Gujrat he C - National capital Sialkot- Samba City, town or village Major road Kathua Line of Control as promulgated in the Lesser road 1972 SIMLA Agreement -- vi Airport Gujranwala Ra Dotted line represents approximately the Line of Control in Jammu and Kashmir agreed upon by India and Pakistan. 32o The final status of Jammu and Kashmir has not been agreed 32o 0 25 50 75 km upon by the parties. -

New Publications Latest Acquisitions

HANSHAN TANG BOOKS • L IST 141 NEW PUBLICATIONS LATEST ACQUISITIONS H ANSHAN TANG B OOKS LTD Unit 3, Ashburton Centre 276 Cortis Road London SW 15 3 AY UK Tel (020) 8788 4464 Fax (020) 8780 1565 Int’l (+44 20) [email protected] www.hanshan.com C ONTENTS N EW & R ECENT P UBLICATIONS / 3 F ROM O UR S TOCK / 11 S UBJECT I NDEX / 60 T ERMS The books advertised in this list are antiquarian, second-hand or new publications. All books listed are in mint or good condition unless otherwise stated. If an out-of-print book listed here has already been sold, we will keep a record of your order and, when we acquire another copy, we will offer it to you. If a book is in print but not immediately available, it will be sent when new stock arrives. We will inform you when a book is not available. Prices take account of condition; they are net and exclude postage. Please note that we have occasional problems with publishers increasing the prices of books on the actual date of publication or supply. For secondhand items, we set the prices in this list. However, for new books we must reluctantly reserve the right to alter our advertised prices in line with any suppliers’ increases. P OSTAL C HARGES & D ISPATCH United Kingdom: For books weighing over 700 grams, minimum postage within the UK is GB £6.50. If books are lighter and we are able to charge less for delivery, we will do so. Dispatch is usually by a trackable three working day courier service. -

A Look Into the Conflict Between India and Pakistan Over Kashmir Written by Pranav Asoori

A Look into the Conflict Between India and Pakistan over Kashmir Written by Pranav Asoori This PDF is auto-generated for reference only. As such, it may contain some conversion errors and/or missing information. For all formal use please refer to the official version on the website, as linked below. A Look into the Conflict Between India and Pakistan over Kashmir https://www.e-ir.info/2020/10/07/a-look-into-the-conflict-between-india-and-pakistan-over-kashmir/ PRANAV ASOORI, OCT 7 2020 The region of Kashmir is one of the most volatile areas in the world. The nations of India and Pakistan have fiercely contested each other over Kashmir, fighting three major wars and two minor wars. It has gained immense international attention given the fact that both India and Pakistan are nuclear powers and this conflict represents a threat to global security. Historical Context To understand this conflict, it is essential to look back into the history of the area. In August of 1947, India and Pakistan were on the cusp of independence from the British. The British, led by the then Governor-General Louis Mountbatten, divided the British India empire into the states of India and Pakistan. The British India Empire was made up of multiple princely states (states that were allegiant to the British but headed by a monarch) along with states directly headed by the British. At the time of the partition, princely states had the right to choose whether they were to cede to India or Pakistan. To quote Mountbatten, “Typically, geographical circumstance and collective interests, et cetera will be the components to be considered[1]. -

![Air Power and National Security[INITIAL].P65](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1427/air-power-and-national-security-initial-p65-191427.webp)

Air Power and National Security[INITIAL].P65

AIR POWER AND NATIONAL SECURITY Indian Air Force: Evolution, Growth and Future AIR POWER AND NATIONAL SECURITY Indian Air Force: Evolution, Growth and Future Air Commodore Ramesh V. Phadke (Retd.) INSTITUTE FOR DEFENCE STUDIES & ANALYSES NEW DELHI PENTAGON PRESS Air Power and National Security: Indian Air Force: Evolution, Growth and Future Air Commodore Ramesh V. Phadke (Retd.) First Published in 2015 Copyright © Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, New Delhi ISBN 978-81-8274-840-8 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without first obtaining written permission of the copyright owner. Disclaimer: The views expressed in this book are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, or the Government of India. Published by PENTAGON PRESS 206, Peacock Lane, Shahpur Jat, New Delhi-110049 Phones: 011-64706243, 26491568 Telefax: 011-26490600 email: [email protected] website: www.pentagonpress.in Branch Flat No.213, Athena-2, Clover Acropolis, Viman Nagar, Pune-411014 Email: [email protected] In association with Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses No. 1, Development Enclave, New Delhi-110010 Phone: +91-11-26717983 Website: www.idsa.in Printed at Avantika Printers Private Limited. This book is dedicated to the memory of my parents, Shri V.V. Phadke and Shrimati Vimal Phadke, My in-laws, Brig. G.S. Sidhu, AVSM and Mrs. Pritam Sidhu, Late Flg. Offr. Harita Deol, my niece, who died in an Avro accident on December 24, 1996, Late Flt. -

1962 Sino-Indian Conflict : Battle of Eastern Ladakh Agnivesh Kumar* Department of Sociology, University of Mumbai, Mumbai, India

OPEN ACCESS Freely available online Journal of Political Sciences & Public Affairs Editorial 1962 Sino-Indian Conflict : Battle of Eastern Ladakh Agnivesh kumar* Department of Sociology, University of Mumbai, Mumbai, India. E-mail: [email protected] EDITORIAL protests. Later they also constructed a road from Lanak La to Kongka Pass. In the north, they had built another road, west of the Aksai Sino-Indian conflict of 1962 in Eastern Ladakh was fought in the area Chin Highway, from the Northern border to Qizil Jilga, Sumdo, between Karakoram Pass in the North to Demchok in the South East. Samzungling and Kongka Pass. The area under territorial dispute at that time was only the Aksai Chin plateau in the north east corner of Ladakh through which the Chinese In the period between 1960 and October 1962, as tension increased had constructed Western Highway linking Xinjiang Province to Lhasa. on the border, the Chinese inducted fresh troops in occupied Ladakh. The Chinese aim of initially claiming territory right upto the line – Unconfirmed reports also spoke of the presence of some tanks in Daulat Beg Oldi (DBO) – Track Junction and thereafter capturing it general area of Rudok. The Chinese during this period also improved in October 1962 War was to provide depth to the Western Highway. their road communications further and even the posts opposite DBO were connected by road. The Chinese also had ample animal In Galwan – Chang Chenmo Sector, the Chinese claim line was transport based on local yaks and mules for maintenance. The horses cleverly drawn to include passes and crest line so that they have were primarily for reconnaissance parties. -

HM 14 APRIL Page 3.Qxd

THE HIMALAYAN MAIL Q JAMMU Q WEDNESDAY Q APRIL 14, 2021 JAMMU & KASHMIR 3 Div Com visits Mukhdoom Sahab Siachen warriors celebrates ‘Siachen Day’ HIMALAYAN MAIL NEWS Shrine, Chatti Padshahi JAMMU, APR 13 On 13 April 2021, Siachen Gurudwara, Ganpatyar Temple Warriors celebrated the 37th Siachen Day with place for devotees, visiting tremendous zeal and enthu- during the festival days. siasm. Brigadier Gurpal He said that today's festi- Singh, SM laid a wreath on vals which are being cele- behalf of GOC, Fire & Fury brated with harmony and Corps and paid homage to brotherhood adds colour to the martyrs at the Siachen its festivity. He said these War Memorial, Base Camp festivals strengthen the to commemorate their bonds of love among people courage and fortitude in se- and nurture amity and har- curing the highest and cold- mony in J&K. est battlefield of the World. During the visit, the com- On this day in 1984, In- mittees of places apprised dian troops first unfurled not only in the face of enemy Soldier continues to guard Siachen Warriors who the Div Com about their is- the tri colour at Bilafond La but also in the face of icy the Frozen Frontier with de- served their motherland sues and demands. He gave launching Operation Megh- peaks with extreme termination and resolve while successfully thwarting HIMALAYAN MAIL NEWS Padshahi Rainawari and arrangements being put in patient hearing to them as- doot. Since then, it has been weather. against all odds. The enemy designs over the SRINAGAR, APR 13 extended his greetings on place for the Holy month of suring that all their genuine a saga of valour and audacity To this day, the Siachen Siachen Day honours all the years. -

Kashmir Conflict: a Critical Analysis

Society & Change Vol. VI, No. 3, July-September 2012 ISSN :1997-1052 (Print), 227-202X (Online) Kashmir Conflict: A Critical Analysis Saifuddin Ahmed1 Anurug Chakma2 Abstract The conflict between India and Pakistan over Kashmir which is considered as the major obstacle in promoting regional integration as well as in bringing peace in South Asia is one of the most intractable and long-standing conflicts in the world. The conflict originated in 1947 along with the emergence of India and Pakistan as two separate independent states based on the ‘Two-Nations’ theory. Scholarly literature has found out many factors that have contributed to cause and escalate the conflict and also to make protracted in nature. Five armed conflicts have taken place over the Kashmir. The implications of this protracted conflict are very far-reaching. Thousands of peoples have become uprooted; more than 60,000 people have died; thousands of women have lost their beloved husbands; nuclear arms race has geared up; insecurity has increased; in spite of huge destruction and war like situation the possibility of negotiation and compromise is still absence . This paper is an attempt to analyze the causes and consequences of Kashmir conflict as well as its security implications in South Asia. Introduction Jahangir writes: “Kashmir is a garden of eternal spring, a delightful flower-bed and a heart-expanding heritage for dervishes. Its pleasant meads and enchanting cascades are beyond all description. There are running streams and fountains beyond count. Wherever the eye -

T He Indian Army Is Well Equipped with Modern

Annual Report 2007-08 Ministry of Defence Government of India CONTENTS 1 The Security Environment 1 2 Organisation and Functions of The Ministry of Defence 7 3 Indian Army 15 4 Indian Navy 27 5 Indian Air Force 37 6 Coast Guard 45 7 Defence Production 51 8 Defence Research and Development 75 9 Inter-Service Organisations 101 10 Recruitment and Training 115 11 Resettlement and Welfare of Ex-Servicemen 139 12 Cooperation Between the Armed Forces and Civil Authorities 153 13 National Cadet Corps 159 14 Defence Cooperaton with Foreign Countries 171 15 Ceremonial and Other Activities 181 16 Activities of Vigilance Units 193 17. Empowerment and Welfare of Women 199 Appendices I Matters Dealt with by the Departments of the Ministry of Defence 205 II Ministers, Chiefs of Staff and Secretaries who were in position from April 1, 2007 onwards 209 III Summary of latest Comptroller & Auditor General (C&AG) Report on the working of Ministry of Defence 210 1 THE SECURITY ENVIRONMENT Troops deployed along the Line of Control 1 s the world continues to shrink and get more and more A interdependent due to globalisation and advent of modern day technologies, peace and development remain the central agenda for India.i 1.1 India’s security environment the deteriorating situation in Pakistan and continued to be infl uenced by developments the continued unrest in Afghanistan and in our immediate neighbourhood where Sri Lanka. Stability and peace in West Asia rising instability remains a matter of deep and the Gulf, which host several million concern. Global attention is shifting to the sub-continent for a variety of reasons, people of Indian origin and which is the ranging from fast track economic growth, primary source of India’s energy supplies, growing population and markets, the is of continuing importance to India. -

Demilitarization of the Siachen Conflict Zone: Concepts for Implementation and Monitoring

SANDIA REPORT SAND2007-5670 Unlimited Release Printed September 2007 Demilitarization of the Siachen Conflict Zone: Concepts for Implementation and Monitoring Brigadier (ret.) Asad Hakeem Pakistan Army Brigadier (ret.) Gurmeet Kanwal Indian Army with Michael Vannoni and Gaurav Rajen Sandia National Laboratories Prepared by Sandia National Laboratories Albuquerque, New Mexico 87185 and Livermore, California 94550 Sandia is a multiprogram laboratory operated by Sandia Corporation, a Lockheed Martin Company, for the United States Department of Energy’s National Nuclear Security Administration under Contract DE-AC04-94AL85000. Approved for public release; further dissemination unlimited. Issued by Sandia National Laboratories, operated for the United States Department of Energy by Sandia Corporation. NOTICE: This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States Government, nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, nor any of their contractors, subcontractors, or their employees, make any warranty, express or implied, or assume any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represent that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government, any agency thereof, or any of their contractors or subcontractors. The views and opinions expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government, any agency thereof, or any of their contractors. Printed in the United States of America. -

Siachen: the Non-Issue, by Prakash Katoch

Siachen: The Non-Issue PC Katoch General Kayani’s call to demilitarise Siachen was no different from a thief in your balcony asking you to vacate your apartment on the promise that he would jump down. The point to note is that both the apartment and balcony are yours and the thief has no business to dictate terms. Musharraf orchestrated the Kargil intrusions as Vajpayee took the bus journey to Lahore, but Kayani’s cunning makes Musharraf look a saint. Abu Jundal alias Syed Zabiuddin an Indian holding an Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) provisioned Pakistani passport has spilled the beans on the 26/11 Mumbai terror attack: its complete planning, training, execution and minute-to-minute directions by the Pakistani military-ISI-LeT (Lashkar-e-Tayyeba) combine. More revealing is the continuing training for similar attacks under the marines in Karachi and elsewhere. The US says Pakistan breeds snakes in its backyard but Pakistan actually beds vipers and enjoys spawning more. If Osama lived in Musharraf’s backyard, isn’t Kayani dining the Hafiz Saeeds and Zaki-Ur- Rehmans, with the Hamid Guls in attendance? His demilitarisation remark post the Gyari avalanche came because maintenance to the Pakistanis on the western slopes of Saltoro was cut off. Yet, the Indians spoke of ‘military hawks’ not accepting the olive branch, recommending that a ‘resurgent’ India can afford to take chances in Siachen. How has Pakistan earned such trust? If we, indeed, had hawks, the cut off Pakistani forces would have been wiped out, following the avalanche. Kashmir Facing the marauding Pakistani hordes in 1947, when Maharaja Hari Singh acceded his state to India, Kashmir encompassed today’s regions of Kashmir Valley, Jammu, Ladakh (all with India), the Northern Areas, Gilgit-Baltistan, Lieutenant General PC Katoch (Retd) is former Director General, Information Systems, Army HQ and a Delhi-based strategic analyst.