Florida Golden Aster Chrysopsis (=Heterotheca) Floridana Small

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bee-Friendly Flowers: Aster

Bee-Friendly Flowers: Aster Like fireworks to celebrate the coming of fall, the vibrant pinks, purples, and whites of the star flowers burst into bloom just as summer flowers fade. They are ubiquitous, lighting up meadows, woodlands, river bottoms, salt marshes, sand dunes, roadsides, and waste places. There are many native species of asters in North America, but it’s hard to put a precise number on them. The problem is that asters used to be classified with their own genus, but recent strides in DNA analysis have made scientists rethink where to put them. Plants that used to be lumped into the genus Aster are now split into Symphiotrichum, Eurybia, Solidago, and Machaeranthera just to name a few. Not all taxonomists are onboard with the change, so many botanical New England aster sources list more than one name for the same plant. Despite the confusion about what to call them, the variety of asters is enormous. Hybridization between species frequently occurs in the wild and there are a plethora of human-created hybrids and cultivars. Some have clouds of tiny flowers and some have blossoms as large as daisies. What they all have in common is that each aster flower is a composite of numerous disc and ray florets, which collectively give the appearance of a single large flower. The center holds the disc florets, which are tubular, house the nectar, and are usually yellow, orange, or brownish in color. Those near the bullseye location have both stamens and pistils and can provide pollen to visiting insects. The outer discs are all females and only have pistils to receive pollen. -

The Vascular Plants of Massachusetts

The Vascular Plants of Massachusetts: The Vascular Plants of Massachusetts: A County Checklist • First Revision Melissa Dow Cullina, Bryan Connolly, Bruce Sorrie and Paul Somers Somers Bruce Sorrie and Paul Connolly, Bryan Cullina, Melissa Dow Revision • First A County Checklist Plants of Massachusetts: Vascular The A County Checklist First Revision Melissa Dow Cullina, Bryan Connolly, Bruce Sorrie and Paul Somers Massachusetts Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program The Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program (NHESP), part of the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife, is one of the programs forming the Natural Heritage network. NHESP is responsible for the conservation and protection of hundreds of species that are not hunted, fished, trapped, or commercially harvested in the state. The Program's highest priority is protecting the 176 species of vertebrate and invertebrate animals and 259 species of native plants that are officially listed as Endangered, Threatened or of Special Concern in Massachusetts. Endangered species conservation in Massachusetts depends on you! A major source of funding for the protection of rare and endangered species comes from voluntary donations on state income tax forms. Contributions go to the Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Fund, which provides a portion of the operating budget for the Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program. NHESP protects rare species through biological inventory, -

State of New York City's Plants 2018

STATE OF NEW YORK CITY’S PLANTS 2018 Daniel Atha & Brian Boom © 2018 The New York Botanical Garden All rights reserved ISBN 978-0-89327-955-4 Center for Conservation Strategy The New York Botanical Garden 2900 Southern Boulevard Bronx, NY 10458 All photos NYBG staff Citation: Atha, D. and B. Boom. 2018. State of New York City’s Plants 2018. Center for Conservation Strategy. The New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, NY. 132 pp. STATE OF NEW YORK CITY’S PLANTS 2018 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6 INTRODUCTION 10 DOCUMENTING THE CITY’S PLANTS 10 The Flora of New York City 11 Rare Species 14 Focus on Specific Area 16 Botanical Spectacle: Summer Snow 18 CITIZEN SCIENCE 20 THREATS TO THE CITY’S PLANTS 24 NEW YORK STATE PROHIBITED AND REGULATED INVASIVE SPECIES FOUND IN NEW YORK CITY 26 LOOKING AHEAD 27 CONTRIBUTORS AND ACKNOWLEGMENTS 30 LITERATURE CITED 31 APPENDIX Checklist of the Spontaneous Vascular Plants of New York City 32 Ferns and Fern Allies 35 Gymnosperms 36 Nymphaeales and Magnoliids 37 Monocots 67 Dicots 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report, State of New York City’s Plants 2018, is the first rankings of rare, threatened, endangered, and extinct species of what is envisioned by the Center for Conservation Strategy known from New York City, and based on this compilation of The New York Botanical Garden as annual updates thirteen percent of the City’s flora is imperiled or extinct in New summarizing the status of the spontaneous plant species of the York City. five boroughs of New York City. This year’s report deals with the City’s vascular plants (ferns and fern allies, gymnosperms, We have begun the process of assessing conservation status and flowering plants), but in the future it is planned to phase in at the local level for all species. -

Notes on Variation and Geography in Rayjacksonia Phyllocephala (Asteraceae: Astereae)

Nesom, G.L., D.J. Rosen, and S.K. Lawrence. 2013. Notes on variation and geography in Rayjacksonia phyllocephala (Asteraceae: Astereae). Phytoneuron 2013-53: 1–15. Published 12 August 2013. ISSN 2153 733X NOTES ON VARIATION AND GEOGRAPHY IN RAYJACKSONIA PHYLLOCEPHALA (ASTERACEAE: ASTEREAE) GUY L. NESOM 2925 Hartwood Drive Fort Worth, Texas 76109 [email protected] DAVID J. ROSEN Department of Biology Lee College Baytown, Texas 77522-0818 [email protected] SHIRON K. LAWRENCE Department of Biology Lee College Baytown, Texas 77522-0818 ABSTRACT Inflorescences of Rayjacksonia phyllocephala in the disjunct Florida population system are characterized by heads on peduncles with leaves mostly reduced to linear bracts; heads in inflorescences of the Mexico-Texas-Louisiana system are immediately subtended by relatively unreduced leaves. The difference is consistent and justifies recognition of the Florida system as R. phyllocephala var. megacephala (Nash) D.B. Ward. Scattered waifs between the two systems are identified here as one or the other variety, directly implying their area of origin. In the eastern range of var. phyllocephala , at least from Brazoria County, Texas, eastward about 300 miles to central Louisiana, leaf margins vary from entire to deeply toothed-spinulose. In contrast, margins are invariably toothed-spinulose in var. megacephala as well as in the rest of southeastern Texas (from Brazoria County southwest) into Tamaulipas, Mexico. In some of the populations with variable leaf margins, 70-95% of the individuals have entire to mostly entire margins. KEY WORDS : Rayjacksonia , morphological variation, leaf margins, disjunction, waifs Rayjacksonia phyllocephala (DC.) Hartman & Lane (Gulf Coast camphor-daisy) is an abundant and conspicuous species of the shore vegetation around the Gulf of Mexico. -

FLORIDA GOLDEN ASTER Chrysopsis Floridana

FLORIDA GOLDEN ASTER Chrysopsis floridana Above: Photo of Florida Golden Aster flower cluster. Photo courtesy of Laurie Markham. Left: Photo of Florida Golden Aster plant. Photo courtesy of Laurie Markham. FAMILY: Asteraceae (Aster family) STATUS: Endangered (Federal Register, May 16, 1986) DESCRIPTION AND REPRODUCTION: Young plants of this perennial herb form rosettes with leaves that are covered with dense, white, short-wooly hairs. Upright stems that grow from the rosettes are 0.3-0.4 meters (1-1.5 feet) tall, with closely-spaced, obovate-elliptic, hairy leaves. The leaves are nearly as large at the top of the stem as at the bottom. The flower heads are arranged in a more or less flat-topped cluster. Each head is slightly over 2.5 centimeters (1 inch) in diameter. Both the central disc and the rays are yellow. This plant is short-lived, and reproduces entirely by seeds. Its seeds are apparently dispersed primarily by the wind. RANGE AND POPULATION LEVEL: Florida golden aster is currently known from Hardee, Hillsborough, Manatee and Pinellas Counties, Florida. 2004 surveys on Hillsborough County lands have discovered several new populations (Cox et al. 2004). Additional survey will be conducted in 2005 on additional Hillsborough and Manatee Counties land. Systematic surveys should be continued and De Soto and Sarasota Counties should be included in this search. Historic sites include Long Key (St. Petersburg Beach) in Pinellas County, and Bradenton Beach and Bradenton in Manatee County. HABITAT: The species grows in open, sunny areas. It occurs in sand pine-evergreen oak scrub vegetation on excessively-drained fine white sand. -

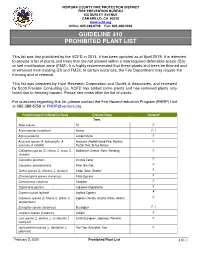

Guideline 410 Prohibited Plant List

VENTURA COUNTY FIRE PROTECTION DISTRICT FIRE PREVENTION BUREAU 165 DURLEY AVENUE CAMARILLO, CA 93010 www.vcfd.org Office: 805-389-9738 Fax: 805-388-4356 GUIDELINE 410 PROHIBITED PLANT LIST This list was first published by the VCFD in 2014. It has been updated as of April 2019. It is intended to provide a list of plants and trees that are not allowed within a new required defensible space (DS) or fuel modification zone (FMZ). It is highly recommended that these plants and trees be thinned and or removed from existing DS and FMZs. In certain instances, the Fire Department may require the thinning and or removal. This list was prepared by Hunt Research Corporation and Dudek & Associates, and reviewed by Scott Franklin Consulting Co, VCFD has added some plants and has removed plants only listed due to freezing hazard. Please see notes after the list of plants. For questions regarding this list, please contact the Fire Hazard reduction Program (FHRP) Unit at 085-389-9759 or [email protected] Prohibited plant list:Botanical Name Common Name Comment* Trees Abies species Fir F Acacia species (numerous) Acacia F, I Agonis juniperina Juniper Myrtle F Araucaria species (A. heterophylla, A. Araucaria (Norfolk Island Pine, Monkey F araucana, A. bidwillii) Puzzle Tree, Bunya Bunya) Callistemon species (C. citrinus, C. rosea, C. Bottlebrush (Lemon, Rose, Weeping) F viminalis) Calocedrus decurrens Incense Cedar F Casuarina cunninghamiana River She-Oak F Cedrus species (C. atlantica, C. deodara) Cedar (Atlas, Deodar) F Chamaecyparis species (numerous) False Cypress F Cinnamomum camphora Camphor F Cryptomeria japonica Japanese Cryptomeria F Cupressocyparis leylandii Leyland Cypress F Cupressus species (C. -

Phytologia an International Journal to Expedite

PHYTOLOGIA An intern ational jou rnal to ex edite la n t s stematic b to eo ra bi l p p y , p y g g p ca and ecological pu blication 1 S e ember 1 1 Vo l. 7 pt 99 CONTENTS TRE M N w ll n n n t r c l fl r . A ne CUA CASAS . c o o o o o o , J , is e a e us tes e pi a a XX species of Humiriastru m 1 65 R T F w f S . rm l rr t n f t c th in the th rn OSS . o co c o o o c t o , , a e i spe i i epi e s s u e . N N H N A eratina nd w f B artlettina ROB S O . o t on a ne c o / I , , es g a spe ies (Eupato rieae : Asteraceae) 1 7 1 /R )BIN N H N w w f C SO . e c and ne comb n on o Crit oniinae from , , spe ies i ati s Meso ame ri ca (Eupato rieae : Asteraceae) 1 76 ’ R B N N H Tw w f Fleiscbman m a fr m M r O S O . o ne c o o m c / I , , spe ies o es a e i a (Eupatorieae : As t eraceae) 1 8 1 /ROBIN N Tw w M le a M SO H. o ne c o f i an i in m r c m , , spe ies esoa e i a (Eupatorieae : As te raceae) 1 84 E AL N D L f f a a r i S C O A F . -

Cocoa Beach Maritime Hammock Preserve Management Plan

MANAGEMENT PLAN Cocoa Beach’s Maritime Hammock Preserve City of Cocoa Beach, Florida Florida Communities Trust Project No. 03 – 035 –FF3 Adopted March 18, 2004 TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION PAGE I. Introduction ……………………………………………………………. 1 II. Purpose …………………………………………………………….……. 2 a. Future Uses ………….………………………………….…….…… 2 b. Management Objectives ………………………………………….... 2 c. Major Comprehensive Plan Directives ………………………..….... 2 III. Site Development and Improvement ………………………………… 3 a. Existing Physical Improvements ……….…………………………. 3 b. Proposed Physical Improvements…………………………………… 3 c. Wetland Buffer ………...………….………………………………… 4 d. Acknowledgment Sign …………………………………..………… 4 e. Parking ………………………….………………………………… 5 f. Stormwater Facilities …………….………………………………… 5 g. Hazard Mitigation ………………………………………………… 5 h. Permits ………………………….………………………………… 5 i. Easements, Concessions, and Leases …………………………..… 5 IV. Natural Resources ……………………………………………..……… 6 a. Natural Communities ………………………..……………………. 6 b. Listed Animal Species ………………………….…………….……. 7 c. Listed Plant Species …………………………..…………………... 8 d. Inventory of the Natural Communities ………………..………….... 10 e. Water Quality …………..………………………….…..…………... 10 f. Unique Geological Features ………………………………………. 10 g. Trail Network ………………………………….…..………..……... 10 h. Greenways ………………………………….…..……………..……. 11 i Adopted March 18, 2004 V. Resources Enhancement …………………………..…………………… 11 a. Upland Restoration ………………………..………………………. 11 b. Wetland Restoration ………………………….…………….………. 13 c. Invasive Exotic Plants …………………………..…………………... 13 d. Feral -

Pennsylvania Natural Heritage Program Plant Species List

Plant Species Page 1 of 19 Home ER Feedback What's New More on PNHP slpecies Lit't~s• " All Species Types " Plants " Vertebrates " Invertebrates Plant Species List " Geologic Features Species " Natural By Community Types Coun ty.FiN Watershed I * Rank and ý7hOW all Species: Status Definitions Records Can Be Sorted By Clicking Column Name * Species Fact Export list to Text Sheets Proposed Global State State Federal Scientific Name Common Name State Rank Rank Status Status * County Natural Status Three-seeded Heritage Acalypha dearnii G4? Sx N PX Mercury Inventories Aconitum reclinatum White Monkshood G3 S1 PE PE (PDF) Aconitum uncinaturn Blue Monkshood G4 S2 PT PT Acorus americanus Sweet Flag G5 S1 PE PE Aleutian Adiantum aleuticum G5? SNR TU TU * Plant Maidenhair Fern Community Aeschynomene Sensitive Joint- G2 Sx PX PX LT Information virginica vetch (PDF)' Eared False- Agalinis auriculata G3 $1 PE PE foxglove Blue-ridge False- Agalinis decemloba G4Q Sx PX PX foxglove o PNDI Project Small-flowered Agalinis paupercula G5 S1 PE PE Planning False-foxglove Environmental Agrostis altissima Tall Bentgrass G4 Sx PX PX Review Aletris farinosa Colic-root G5 S1 TU PE Northern Water- Alisma triviale G5 S1 PE PE NOTE:Clicking plantain this link opens a Alnus viridis Mountain Alder G5 S1 PE PE new browser Alopecurus aequalis Short-awn Foxtail G5 S3 N TU PS window Amaranthus Waterhemp G5 S3 PR PR cannabinus Ragweed Amelanchier Oblong-fruited G5 $1 PE PE bartramiana Serviceberry Amelanchier Serviceberry G5 SNR N UEF canadensis http://www.naturalheritage.state.pa.us/PlantsPage.aspx -

Download The

SYSTEMATICA OF ARNICA, SUBGENUS AUSTROMONTANA AND A NEW SUBGENUS, CALARNICA (ASTERACEAE:SENECIONEAE) by GERALD BANE STRALEY B.Sc, Virginia Polytechnic Institute, 1968 M.Sc, Ohio University, 1974 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Department of Botany) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA March 1980 © Gerald Bane Straley, 1980 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department nf Botany The University of British Columbia 2075 Wesbrook Place Vancouver, Canada V6T 1W5 26 March 1980 ABSTRACT Seven species are recognized in Arnica subgenus Austromontana and two species in a new subgenus Calarnica based on a critical review and conserva• tive revision of the species. Chromosome numbers are given for 91 populations representing all species, including the first reports for Arnica nevadensis. Results of apomixis, vegetative reproduction, breeding studies, and artifi• cial hybridizations are given. Interrelationships of insect pollinators, leaf miners, achene feeders, and floret feeders are presented. Arnica cordifolia, the ancestral species consists largely of tetraploid populations, which are either autonomous or pseudogamous apomicts, and to a lesser degree diploid, triploid, pentaploid, and hexaploid populations. -

Fort Ord Natural Reserve Plant List

UCSC Fort Ord Natural Reserve Plants Below is the most recently updated plant list for UCSC Fort Ord Natural Reserve. * non-native taxon ? presence in question Listed Species Information: CNPS Listed - as designated by the California Rare Plant Ranks (formerly known as CNPS Lists). More information at http://www.cnps.org/cnps/rareplants/ranking.php Cal IPC Listed - an inventory that categorizes exotic and invasive plants as High, Moderate, or Limited, reflecting the level of each species' negative ecological impact in California. More information at http://www.cal-ipc.org More information about Federal and State threatened and endangered species listings can be found at https://www.fws.gov/endangered/ (US) and http://www.dfg.ca.gov/wildlife/nongame/ t_e_spp/ (CA). FAMILY NAME SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME LISTED Ferns AZOLLACEAE - Mosquito Fern American water fern, mosquito fern, Family Azolla filiculoides ? Mosquito fern, Pacific mosquitofern DENNSTAEDTIACEAE - Bracken Hairy brackenfern, Western bracken Family Pteridium aquilinum var. pubescens fern DRYOPTERIDACEAE - Shield or California wood fern, Coastal wood wood fern family Dryopteris arguta fern, Shield fern Common horsetail rush, Common horsetail, field horsetail, Field EQUISETACEAE - Horsetail Family Equisetum arvense horsetail Equisetum telmateia ssp. braunii Giant horse tail, Giant horsetail Pentagramma triangularis ssp. PTERIDACEAE - Brake Family triangularis Gold back fern Gymnosperms CUPRESSACEAE - Cypress Family Hesperocyparis macrocarpa Monterey cypress CNPS - 1B.2, Cal IPC -

Erigeron Speciosus (Lindl.) DC

ASPEN FLEABANE Erigeron speciosus (Lindl.) DC. Asteraceae – Aster family Corey L. Gucker & Nancy L. Shaw | 2018 ORGANIZATION NOMENCLATURE Erigeron speciosus (Lind.) DC., hereafter Names, subtaxa, chromosome number(s), hybridization. referred to as aspen fleabane, belongs to the Astereae tribe of the Asteraceae or aster family (Nesom 2006). Range, habitat, plant associations, elevation, soils. NRCS Plant Code. ERSP4 (USDA NRCS 2018). Synonyms. Erigeron conspicuus Rydberg; E. macranthus Nuttall; E. speciosus var. conspicuus (Rydberg) Breitung; E. speciosus Life form, morphology, distinguishing characteristics, reproduction. var. macranthus (Nuttall) Cronquist; E. subtrinervis Rydberg ex Porter & Britton subsp. conspicuus (Rydberg) Cronquist; Growth rate, successional status, disturbance ecology, importance to E. subtrinervis var. conspicuus (Rydberg) animals/people. Cronquist, Stenactis speciosa Lindley (Nesom 2006). Current or potential uses in restoration. Common Names. Aspen fleabane, Oregon fleabane, Oregon wild-daisy, showy daisy, showy fleabane (USDA FS 1937; Nesom 2006; AOSA 2016; USDA NRCS 2018). Seed sourcing, wildland seed collection, seed cleaning, storage, testing and marketing standards. Subtaxa. No varieties or subspecies are currently recognized by the Flora of North America (Nesom 2006). Recommendations/guidelines for producing seed. Chromosome Number. Chromosome numbers are 2n = 18, 36 (Jones and Young 1983; Welsh et al. 1987). Recommendations/guidelines for producing planting stock. Hybridization. Distributions of aspen fleabane and threenerve fleabane (E. subtrinervis) have considerable overlap, and although they are Recommendations/guidelines, wildland restoration successes/ considered at least partially reproductively failures. isolated, intermediate forms are common (Nesom 2006). Primary funding sources, chapter reviewers. DISTRIBUTION Bibliography. Aspen fleabane is widely distributed throughout western North America. In Canada, it occurs in British Columbia and Alberta.