FAO Regional Initiative in Support to Vulnerable Pastoralists and Agro

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Districts of Ethiopia

Region District or Woredas Zone Remarks Afar Region Argobba Special Woreda -- Independent district/woredas Afar Region Afambo Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Asayita Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Chifra Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Dubti Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Elidar Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Kori Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Mille Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Abala Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Afdera Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Berhale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Dallol Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Erebti Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Koneba Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Megale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Amibara Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Awash Fentale Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Bure Mudaytu Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Dulecha Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Gewane Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Aura Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Ewa Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Gulina Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Teru Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Yalo Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Dalifage (formerly known as Artuma) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Dewe Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Hadele Ele (formerly known as Fursi) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Simurobi Gele'alo Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Telalak Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Amhara Region Achefer -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Angolalla Terana Asagirt -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Artuma Fursina Jile -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Banja -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Belessa -- -

ETHIOPIA - National Hot Spot Map 31 May 2010

ETHIOPIA - National Hot Spot Map 31 May 2010 R Legend Eritrea E Tigray R egion !ª D 450 ho uses burned do wn d ue to th e re ce nt International Boundary !ª !ª Ahferom Sudan Tahtay Erob fire incid ent in Keft a hum era woreda. I nhabitan ts Laelay Ahferom !ª Regional Boundary > Mereb Leke " !ª S are repo rted to be lef t out o f sh elter; UNI CEF !ª Adiyabo Adiyabo Gulomekeda W W W 7 Dalul E !Ò Laelay togethe r w ith the regiona l g ove rnm ent is Zonal Boundary North Western A Kafta Humera Maychew Eastern !ª sup portin g the victim s with provision o f wate r Measle Cas es Woreda Boundary Central and oth er imm ediate n eeds Measles co ntinues to b e re ported > Western Berahle with new four cases in Arada Zone 2 Lakes WBN BN Tsel emt !A !ª A! Sub-city,Ad dis Ababa ; and one Addi Arekay> W b Afa r Region N b Afdera Military Operation BeyedaB Ab Ala ! case in Ahfe rom woreda, Tig ray > > bb The re a re d isplaced pe ople from fo ur A Debark > > b o N W b B N Abergele Erebtoi B N W Southern keb eles of Mille and also five kebeles B N Janam ora Moegale Bidu Dabat Wag HiomraW B of Da llol woreda s (400 0 persons) a ff ected Hot Spot Areas AWD C ases N N N > N > B B W Sahl a B W > B N W Raya A zebo due to flo oding from Awash rive r an d ru n Since t he beg in nin g of th e year, Wegera B N No Data/No Humanitarian Concern > Ziquala Sekota B a total of 967 cases of AWD w ith East bb BN > Teru > off fro m Tigray highlands, respective ly. -

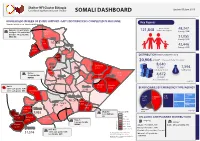

Somali Dashboard +Distribution Breakdown

Shelter-NFI Cluster Ethiopia Coordinating Humanitarian Shelter SOMALI DASHBOARD Update 05 June 2018 HOUSEHOLDS IN NEED OF ES/NFI SUPPORT- GAP*/ DISTRIBUTIONS COMPLETED IN MAY/JUNE Key Figures *Number of HH inGA need - Number of HH suported HH in need of 48,347 Gablalu- 100 partial kits 121,848 Shelter/ NFI support Hadigala- 330 partial kits Gablablu Priority 1 HH Dembel- 140 partial kits 1,673 ERCS/IRC 31,055 Siti Priority 2 HH Erer 10,808 2,630 Fafan 42,446 Miesso Priority 3 HH 3,598 15,157 Jijiga DISTRIBUTION SINCE JANUARY 2018 Babile 1,464 10, 592 20,906 (2,482)* HH received Shelter/ NFI support Erer Gashamo 8,640 4,941 Jarar 3, 733 (1,390)* 7,594 Full Shelter/NFI kits Cash Grants Qubi 7, 343 S Berano Boh 2,114 500 partial kits Noqob Danot Doolo 1,546 4,672 NDRMC 2,537 (1,102)* 3,841 Gerbo 12,068 Partial Shelter/NFI kits 1,476 on-going* Warder Geladin Hudet Korahe 3,712 2,144 BENEFICIARIES BY EMERGENCY TYPE/AGENCY 1,500 cash grants- IOM 3,193 1,000 cash grants- NRC Guradamole Berano 2,720 290 NRC CONCERN CONFLICTIOM Shabelle FLOOD CONFLICT 3,630 2,602 9,0507,094 7,462 9,050 Karsa Dulla 16, 578 (2,482)* IRC/ERCS Afder Kelafo 2,570 1,449 Hargele 9,520 SCI 7,033 702 Mustahil 3,000 NDRMC 2,000 Deka Suftu 3,419 Liben DROUGHT 2,364 on-going* Mustahil Number of HH 3,814 9,955 1,000 fulll kits Hudet 0 SCI 1 - 500 12,718 Mubarak ON-GOING AND PLANNED DISTRIBUTIONS Dolo Odo 500 - 1,000 6,002 Hargele on-going 1,989 1,500 partial kits 1,000 - 2,000 planned 2,000 - 5,000 Moyale NDRMC Adadle- 750 full kits /NRC Kelafo- 450 partial kits /SCI 5,000 -

11 HS 000 ETH 013013 A4.Pdf (English)

ETHIOPIA:Humanitarian Concern Areas Map (as of 04 February 2013) Eritrea > !ª !ª> Note: The following newly created woreda boundaries are not Tahtay !ª E available in the geo-database; hence not represented in this Nutrition Hotspot Priority Laelay Erob R R !ª Adiyabo Mereb Ahferom !ª Tahtay Gulomekeda !ª I E map regardless of their nutrition hot spot priority 1 & 2: Adiyabo Leke T D Adiyabo Adwa Saesie Dalul Priority one Asgede Tahtay R S Kafta Werei Tsaedaemba E E Priority 1: Dawa Sarar (Bale zone), Goro Dola (Guji zone), Abichu Tsimbila Maychew !ª A Humera Leke Hawzen Berahle A Niya( North Showa zone) and Burka Dintu (West Hararge Priority two > T I GR AY > Koneba Central Berahle zone) of Oromia region, Mekoy (Nuer zone) of Gambella Western Naeder Kola Ke>lete Awelallo Priority three Tselemti Adet Temben region, Kersadula and Raso (Afder zone), Ararso, Birkod, Tanqua > Enderta !ª Daror and Yo'ale (Degahabour zone), Kubi (Fik zone), Addi Tselemt Zone 2 No Priority given Arekay Abergele Southern Ab Ala Afdera Mersin (Korahe zone), Dhekasuftu and Mubarek (Liben Beyeda Saharti Erebti Debark Hintalo !ª zone), Hadigala (Shinille zone) and Daratole (Warder Abergele Samre > Megale Erebti Bidu Wejirat zone) of Somali region. Dabat Janamora > Bidu International Boundary Alaje Raya North Lay Sahla Azebo > Wegera Endamehoni > > Priority 2: Saba Boru (Guji zone) of Oromia region and Ber'ano Regional Boundary Gonder Armacho Ziquala > A FA R !ª East Sekota Raya Yalo Teru (Gode zone) and Tulu Guled (Jijiga zone) of Somali region. Ofla Kurri Belesa -

Eastern Africa: Security and the Legacy of Fragility

Eastern Africa: Security and the Legacy of Fragility Africa Program Working Paper Series Gilbert M. Khadiagala OCTOBER 2008 INTERNATIONAL PEACE INSTITUTE Cover Photo: Elderly women receive ABOUT THE AUTHOR emergency food aid, Agok, Sudan, May 21, 2008. ©UN Photo/Tim GILBERT KHADIAGALA is Jan Smuts Professor of McKulka. International Relations and Head of Department, The views expressed in this paper University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South represent those of the author and Africa. He is the co-author with Ruth Iyob of Sudan: The not necessarily those of IPI. IPI Elusive Quest for Peace (Lynne Rienner 2006) and the welcomes consideration of a wide range of perspectives in the pursuit editor of Security Dynamics in Africa’s Great Lakes of a well-informed debate on critical Region (Lynne Rienner 2006). policies and issues in international affairs. Africa Program Staff ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS John L. Hirsch, Senior Adviser IPI owes a great debt of thanks to the generous contrib- Mashood Issaka, Senior Program Officer utors to the Africa Program. Their support reflects a widespread demand for innovative thinking on practical IPI Publications Adam Lupel, Editor solutions to continental challenges. In particular, IPI and Ellie B. Hearne, Publications Officer the Africa Program are grateful to the government of the Netherlands. In addition we would like to thank the Kofi © by International Peace Institute, 2008 Annan International Peacekeeping Training Centre, which All Rights Reserved co-hosted an authors' workshop for this working paper series in Accra, Ghana on April 11-12, 2008. www.ipinst.org CONTENTS Foreword, Terje Rød-Larsen . i Introduction. 1 Key Challenges . -

MIND the GAP Commercialization, Livelihoods and Wealth Disparity in Pastoralist Areas of Ethiopia

MIND THE GAP Commercialization, Livelihoods and Wealth Disparity in Pastoralist Areas of Ethiopia Yacob Aklilu and Andy Catley December 2010 Contents Summary ..................................................................................................................................................... 1 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................................ 3 1.1 Objectives .............................................................................................................................................. 4 1.2 Methodology ......................................................................................................................................... 4 1.3 Structure of the report .......................................................................................................................... 5 2. Livestock exports from pastoral areas of Ethiopia: recent trends and issues ......................................... 6 2.1 The growing trade: economic gains outweigh ethnicity and trust........................................................ 7 2.2 The cross‐border trade from Somali Region and Borana ...................................................................... 8 2.3 Trends in formal exports from Ethiopia .............................................................................................. 12 2.4 A boom in prices and the growth of bush markets ............................................................................ -

Addressing the Lack of Evaluation Capacity in Post

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by University of Minnesota Digital Conservancy ADDRESSING THE LACK OF EVALUATION CAPACITY IN POST-CONFLICT SOMALIA A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Ibrahim Abikar Noor IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Jean A. King, Co-Advisor Christopher Johnstone, Co-Advisor March, 2018 © Ibrahim Abikar Noor Acknowledgments As my dissertation writing is coming to a close, I would like to take this opportunity to thank each and every person who has contributed to making this journey a success. I greatly appreciate your endeavors. I especial thank my co- advisors Dr. Jean King and Dr. Christopher Johnstone for their guidance and support. Dr. King perked up my interest in evaluation with few minutes the first time I met her in her office. Dr. Johnstone was available come rain or shine. He even answered my phone call while in flight. These fine professors have really been there for me all the way. A similar thank you goes to Dr. Karen Storm and Dr. David Johnson for steering me back when I veered off course. The completion of this dissertation would have been in question without my niece Zahra Ahmed, who offered her language and organizational skill, and my friend Wayne Johnson for continuously encouraging me to keep going. Finally, I want to dedicate this work to my wife and children for being patient and understanding when I could not join them for family events. My youngest son Ilyas was extremely tolerant when I sometimes skipped fun time with him. -

Periodic Monitoring Report Working 2016 Humanitarian Requirements Document – Ethiopia Group

DRMTechnical Periodic Monitoring Report Working 2016 Humanitarian Requirements Document – Ethiopia Group Covering 1 Jan to 31 Dec 2016 Prepared by Clusters and NDRMC Introduction The El Niño global climactic event significantly affected the 2015 meher/summer rains on the heels of failed belg/ spring rains in 2015, driving food insecurity, malnutrition and serious water shortages in many parts of the country. The Government and humanitarian partners issued a joint 2016 Humanitarian Requirements Document (HRD) in December 2015 requesting US$1.4 billion to assist 10.2 million people with food, health and nutrition, water, agriculture, shelter and non-food items, protection and emergency education responses. Following the delay and erratic performance of the belg/spring rains in 2016, a Prioritization Statement was issued in May 2016 with updated humanitarian requirements in nutrition (MAM), agriculture, shelter and non-food items and education.The Mid-Year Review of the HRD identified 9.7 million beneficiaries and updated the funding requirements to $1.2 billion. The 2016 HRD is 69 per cent funded, with contributions of $1.08 billion from international donors and the Government of Ethiopia (including carry-over resources from 2015). Under the leadership of the Government of Ethiopia delivery of life-saving and life- sustaining humanitarian assistance continues across the sectors. However, effective humanitarian response was challenged by shortage of resources, limited logistical capacities and associated delays, and weak real-time information management. This Periodic Monitoring Report (PMR) provides a summary of the cluster financial inputs against outputs and achievements against cluster objectives using secured funding since the launch of the 2016 HRD. -

Good Practice Guidelines for Water Development

SOMALI REGIONAL STATE OF ETHIOPIA Achieving Water Security Enhancing Ensuring Water Water Productivity Sustainability GOOD PRACTICE GUIDELINES FOR WATER DEVELOPMENT SOMALI REGIONAL STATE OF ETHIOPIA GOOD PRACTICE GUIDELINES FOR WATER DEVELOPMENT Correct Citation: Somali Regional State of Ethiopia. (2012). Good Practice Guidelines for Water Development. Office of the President, Somali Regional State of Ethiopia, Jijiga, Ethiopia, 89 pp. Table of Contents Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................................................ i Abbreviations ............................................................................................................................................... iii Preface .......................................................................................................................................................... v Chapter 1: Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 1 1.1. Water Resource Development in Somali Region .......................................................................... 1 1.2. About the Guidelines .................................................................................................................... 3 1.3. How to Use These Guidelines ....................................................................................................... 5 Chapter 2: Water Resource in Somali Region and General Strategic -

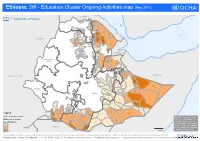

Ethiopia: 3W - Education Cluster Ongoing Activities Map (May 2017)

Ethiopia: 3W - Education Cluster Ongoing Activities map (May 2017) ERITREA 5 Total Number of Partners MoE ☄ UNICEF Erob Dalul WFP MoE MoE Berahile Red Sea WFP MoE WFP Kelete MoE Awelallo UNICEF MoE TIGRAY Tselemti UNICEF Tselemt UNICEF MoE AFAR UNICEF MoE MoE WFP Beyeda Afdera Bidu Tanqua MoE UNICEF MoE Abergele Janamora Megale WFP Erebti MoE WFP Gulf of MoE Sahla UNICEF MoE Teru Kurri Aden Raya WFP UNICEF MoE Azebo MoE East UNICEF Elidar WFP WFP SUDAN Belesa Sekota UNICEF UNICEF West UNICEF MoE MoE Belesa UNICEF WFP MoE Yalo MoE Dehana MoE WFP WFP UNICEF UNICEF UNICEF WFP MoE MoE MoE MoE MoE Kobo Ebenat Awra MoE AMHARA MoE Meket Ewa Chifra WFP Aysaita UNICEF UNICEF Simada UNICEF WFP WFP UNICEF Adaa'r MoE UNICEF UNICEF MoE Bati Telalak DJIBOUTI UNICEF WFP Sayint MoE MoE MoE UNICEF UNICEF Enbise WFP UNICEF Ayisha WFP Dewa Sar Midir WFP MoE WFP Harewa BENISHANGUL MoE UNICEF Gewane GUMUZ WFP UNICEF WFP MoE Bure WFP Mudaytu SOMALI Hadelela WFP Shinile WFP UNICEF Afdem Simurobi Aw-bare Dembel Gele'alo UNICEF Miesso WFP WFP WFP Erer DIRE Chinaksen MoE Amibara MoE Jijiga WFP DAWA UNICEF UNICEF MoE WFP WFP WFP HARERI Gursum MoE Fedis Gursum WFP WFP MoE WFP MoE Babile MoE Hareshen Malka MoE Aware SOMALIA SOUTH SUDAN UNICEF Balo UNICEF Kebribeyah MoE Anchar Babile Midega Boke Golo Oda Meyu Oxfam UNICEF Tola UNICEF WFP WFP Oxfam MoE MoE WFP WFP UNICEF Fik WFP MoE WFP WFP Gashamo Dodota Dodota Lagahida MoE WFP Hawi MoE WFP Degehamedo Degehabur WFP Gudina MoE WFP WFP MoE MoE Gunagado Danot Lege Hamero Hida Gerbo GAMBELA Selahad WFP Shekosh Alaba SP -

Capitalizing on Trust

CAPITALIZING ON TRUST Harnessing Somali Remittances for Counterterrorism, Human Rights and State Building BY JAMES COCKAYNE WITH LIAT SHETRET Copyright © 2012 Center on Global Counterterrorism Cooperation All rights reserved. For permission requests, write to the publisher at: 803 North Main Street Goshen, IN 46528, USA ISBN: 978-0-9853060-0-7 Design: Stislow Design Front cover photo credit: © Jim Mone/ /AP/Corbis Somali Americans rally at the Minnesota State Capitol to protest the closure of money service businesses Friday, Jan. 6, 2012, in St. Paul, Minn. They are asking banks to restore relations with the companies wiring money to millions of Somali refugees in the Horn of Africa. Suggested citation: James Cockayne with Liat Shetret. “Capitalizing on Trust Harnessing Somali Remittances for Counterterrorism, Human Rights and State Building.” Center on Global Counterterrorism Cooperation. March 2012. Table of Contents About the Center on Global Counterterrorism INTERNATIONAL EFFORTS: BETWEEN Cooperation . ii FORMALIZATION AND PARTNERSHIP . 36 NATIONAL EFFORTS: PRAGMATIC CONVERGENCE? . 38 Research Team . ii Challenges in Implementation . 41 Acknowledgments . .. iii HOW DO YOU KNOW YOUR CUSTOMER? . 41 WHAT IS A SUSPICIOUS TRANSACTION? . 44 Glossary and Acronyms . iv WHO IS A POLITICALLY EXPOSED PERSON IN SOMALIA? . 45 WHERE DO BANKS FIT IN? . 46 Executive Summary . v WHERE DO TRADE ASSOCIATIONS FIT IN? . 47 Introduction . 2 Regulatory Confusion? . 48 Methodology . 5 Terminology . 6 3 . Harnessing the Potential of Somali Difficulties for and Limitations Remittances . 51 of the Research . 7 Capitalizing on Trust: From Confidence Building Implications of the Research Beyond to State Building . 51 Somali Remittances . 7 How Do We Get There? Recommendations for Action . -

RESILIENCE in ACTION Drylands CONTENTS

Changing RESILIENCE Horizons in Ethiopia’s IN ACTION Drylands PEOPLE AND COMMUNITIES 3 Changing RESILIENCE Horizons in Ethiopia’s IN ACTION Drylands Changing Horizons in Ethiopia’s RESILIENCE IN ACTION Drylands CONTENTS 4 FOREWORD 6 PEOPLE AND COMMUNITIES 34 LIVESTOCK AND MARKETS 56 PASTURE AND WATER 82 CHANGING HORIZONS 108 USAID’S PARTNERS 112 ABOUT USAID 2 RESILIENCE IN ACTION PASTURE AND WATER 3 FOREWORD MAP OF ETHIOPIA’S DRYLANDS ERITREA National Capital TIGRAY YEMEN Regional Capitals Dry Lands Regional Boundaries SUDAN National Boundary AFAR DJIBOUTI AMHARA BINSHANGUL- GAMUZ SOMALIA OROMIYA GAMBELLA ETHIOPIA SOMALI OROMIYA SOUTH SNNP SUDAN SOMALIA UGANDA KENYA re·sil·ience /ri-zíl-yuh ns/ noun The ability of people, households, communities, countries, and systems to mitigate, adapt to, and recover from shocks and stresses in a manner that reduces chronic vulnerability and facilitates inclusive growth. ETHIOPIA’S enormous pastoral pop- minimized thanks to USAID’s support for commercial Our approach in Ethiopia recognizes these dynamics, giving them better access to more reliable water resources ulation is estimated at 12 to 15 million destocking and supplementary livestock feeding, which working closely with communities while developing and reducing the need to truck in water, a very expensive people, the majority of whom live in supplied fodder to more than 32,000 cattle, sheep, and relationships with new stakeholders, such as small proposition, in future droughts which are occurring at a the arid or semi-arid drylands that goats. In addition, households were able to slaughter the businesses in the private sector (for instance, slaughter- higher frequency than in past decades.