Losing a Best Friend

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

New Voices Lander University’S Student Journal

New Voices Lander University’s Student Journal -Spring 2019- New Voices is a publication of the College of Arts and Humanities Lander University 320 Stanley Avenue Greenwood, SC 29649 Student Editorial Board: Delshawn Anderson Carrie Floth Faculty Advisors: Dr. Misty Jameson Dr. Andy Jameson Prof. Dusty McGee-Anderson Congratulations to Devon Bowie, Winner of the 2019 Dessie Dean Pitts Award, Margaret Gustafson, Winner of the 2019 Creative Writing Award, and Berrenger Franklin, whose artwork Heart was selected as this year’s cover. [email protected] www.facebook.com/newvoicesLU Table of Contents Sunset across the Lake by Diamond Crawford . 3 “More Human than Human” by Devon Bowie. 4 “Tachycardia” by Margaret Gustafson. 7 “Unsolved” by Margaret Gustafson. 9 Aerodynamic Decline by Valencia Haynes . 10 “I Own You” by Haven Pesce . 11 “Revival” by Jesse Cape . 13 Youthful Devastation by Valencia Haynes . 17 “Walls” by Dale Hensarling. 18 “H.U.D.S.” by Dale Hensarling . 24 Doors at 8, Show at 9 by Valencia Haynes. 25 “The Commute” by Sophie Oder. 26 “Wonderland and the Looking Glass Worlds: Parallels to Victorian English Government and Law” by Eden Weidman . 30 “The Lights That Disappeared” by Ashlyn Wilson. 35 Haze Reaches Heights by Valencia Haynes. 36 Acknowledgements. 37 Dedication. 38 Sunset across the Lake by Diamond Crawford - 3 - “More Human than Human” Dessie Dean Pitts Award Winner by Devon Bowie In the novel Frankenstein by Mary Shelley, there is an overlying debate over what it means to be human. Throughout the novel, Victor Frankenstein emphasizes how his Creature is inhuman—sometimes superhuman, sometimes less than human—but the reader is shown time and again that the Creature possesses an intense, pure, unfiltered form of humanity. -

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

The Moment As of Late

flILL 1990 . Three Dollars $ 3 0 ENT A Randomly Published L. A. Journal of the Arts =#=/J INSIDE: BUKOWSKI, GINSBERG, EDIE KEROUAC, IG.OR ORLOVSKllVICHSTEINIAN, & L.A.'s BEST POETS! - More John W. Hart III News! -Bye-Bye Bebop! After many John was the guest on DodgerTalk, years as the boheme headquarters of the K A BC Dodger Talk Show - a MOMENT the San Fernando Valley, Bebop dream-come-true for Ill and another Records and Fine Arts has packed small step I giant leap for poetry! their bags and moved on. Where? BY Well, Bebop is always everywhere! Owner Richard Bruland, who has MOMENT featured poetry and music over the years in his cozy used-record store and f me art gallery, took it all in stride. Rumors flew that the police IN THIS GODDAMNED ISSUE! But, in the Meantime, the CELEBRITY SIGHTINGS - following were occurrences of vital Many a star, darlink, did indeed ' chased away "those crazy arteests," BUKOWSKI POETRY! AND importance, so read them carefully ... receive the Moment as of late ... you but who really knows?!. .. perhaps FRONT AND BACK COVER! - Bukowski came out with got your Matthew Broderick with Bebop's time had simply come. Septuagenarian Stew! And a great Helen Bunt in San Francisco Tharkyou, Richard and Bebop, for GINSBERG HAIKU! book it is indeed. And happy 70 to ya strolling down the street happily the ~any , many ~emories of poetry BUK and happy anniversary, blah accepting a little bit of poetry: and readings, open mike nights, music, EDIE KEROUAC INTERVIEW! blah .. More importantly, we rapped Ken Osmond (aka Eddie Haskell) and good times. -

33 UCLA L. Rev. 379 December, 1985

UCLA LAW REVIEW 33 UCLA L. Rev. 379 December, 1985 RULES AND STANDARDS Pierre J. Schlag a1 © 1985 by the Regents of the University of California; Pierre J. Schlag INTRODUCTION Every student of law has at some point encountered the “bright line rule” and the “flexible standard.” In one torts casebook, for instance, Oliver Wendell Holmes and Benjamin Cardozo find themselves on opposite sides of a railroad crossing dispute.1 They disagree about what standard of conduct should define the obligations of a driver who comes to an unguarded railroad crossing. Holmes offers a rule: The driver must stop and look.2 Cardozo rejects the rule and instead offers a standard: The driver must act with reasonable caution.3 Which is the preferable approach? Holmes suggests that the requirements of due care at railroad crossings are clear and, therefore, it is appropriate to crystallize these obligations into a simple rule of law.4 Cardozo counters with scenarios in which it would be neither wise nor prudent for a driver to stop and look.5 Holmes might well have answered that Cardozo’s scenarios are exceptions and that exceptions prove the rule. Indeed, Holmes might have parried by suggesting that the definition of a standard of conduct by means of a legal rule is predictable and certain, whereas standards and juries are not. This dispute could go on for quite some time. But let’s leave the substance of this dispute behind and consider some observations about its form. First, disputes that pit a rule against a standard are extremely common in legal discourse. -

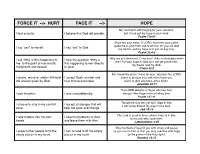

FORCE IT FACE IT HOPE Handout

FORCE IT --> HURT FACE IT --> HOPE My soul faints with longing for your salvation, ! I fear scarcity. I believe that God will provide. but I have put my hope in your word.! Psalm 119:81 Show me your ways, O LORD, teach me your paths; ! guide me in your truth and teach me, for you are God ! I say “yes” to myself. I say “yes” to God. my Savior, and my hope is in you all day long. ! Psalm 25:4-5 I ask “Why is this happening to I take the question “Why is Why are you downcast, O my soul? Why so disturbed within me? Put your hope in God, for I will yet praise him, ! me” to the point of narcissistic this happening to me” directly my Savior and my God.! martyrdom and despair. to God. Psalm 42:5 For I know the plans I have for you," declares the LORD, I ignore, mis-use, and/or withhold I accept God’s answer and "plans to prosper you and not to harm you, ! the answer given by God. trust Him to know best. plans to give you hope and a future.! Jeremiah 29:11 The LORD delights in those who fear him, ! I pick favorites. I love unconditionally. who put their hope in his unfailing love.! Psalm 147:11 Though he slay me, yet will I hope in him; ! I choose to stay in my comfort I accept challenges that will I will surely defend my ways to his face.! zone. help me grow and change. Job 13:15 The Lord is good to those whose hope is in him, ! I take matters into my own I take my problems to God to the one who seeks him; ! hands. -

Flannery O'connor's Images of the Self

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Fall 1978 CLOWNS AND CAPTIVES: FLANNERY O'CONNOR'S IMAGES OF THE SELF MICHAEL JOHN LEE Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation LEE, MICHAEL JOHN, "CLOWNS AND CAPTIVES: FLANNERY O'CONNOR'S IMAGES OF THE SELF" (1978). Doctoral Dissertations. 1210. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/1210 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document ' ave been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or “ target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. -

Voices in the Hall: Sam Bush (Part 1) Episode Transcript

VOICES IN THE HALL: SAM BUSH (PART 1) EPISODE TRANSCRIPT PETER COOPER Welcome to Voices in the Hall, presented by the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum. I’m Peter Cooper. Today’s guest is a pioneer of New-grass music, Sam Bush. SAM BUSH When I first started playing, my dad had these fiddle albums. And I loved to listen to them. And then realized that one of the things I liked about them was the sound of the fiddle and the mandolin playing in unison together. And that’s when it occurred to me that I was trying on the mandolin to note it like a fiddle player notes. Then I discovered Bluegrass and the great players like Bill Monroe of course. You can specifically trace Bluegrass music to the origins. That it was started by Bill Monroe after he and his brother had a duet of mandolin and guitar for so many years, the Monroe Brothers. And then when he started his band, we're just fortunate that he was from the state of Kentucky, the Bluegrass State. And that's why they called them The Bluegrass Boys. And lo and behold we got Bluegrass music out of it. PETER COOPER It’s Voices in the Hall, with Sam Bush. “Callin’ Baton Rouge” – New Grass Revival (Best Of / Capitol) PETER COOPER “Callin’ Baton Rouge," by the New Grass Revival. That song was a prime influence on Garth Brooks, who later recorded it. Now, New Grass Revival’s founding member, Sam Bush, is a mandolin revolutionary whose virtuosity and broad- minded approach to music has changed a bunch of things for the better. -

Buffy's Glory, Angel's Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic

Please do not remove this page Giving Evil a Name: Buffy's Glory, Angel's Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic Croft, Janet Brennan https://scholarship.libraries.rutgers.edu/discovery/delivery/01RUT_INST:ResearchRepository/12643454990004646?l#13643522530004646 Croft, J. B. (2015). Giving Evil a Name: Buffy’s Glory, Angel’s Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic. Slayage: The Journal of the Joss Whedon Studies Association, 12(2). https://doi.org/10.7282/T3FF3V1J This work is protected by copyright. You are free to use this resource, with proper attribution, for research and educational purposes. Other uses, such as reproduction or publication, may require the permission of the copyright holder. Downloaded On 2021/10/02 09:39:58 -0400 Janet Brennan Croft1 Giving Evil a Name: Buffy’s Glory, Angel’s Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic “It’s about power. Who’s got it. Who knows how to use it.” (“Lessons” 7.1) “I would suggest, then, that the monsters are not an inexplicable blunder of taste; they are essential, fundamentally allied to the underlying ideas of the poem …” (J.R.R. Tolkien, “Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics”) Introduction: Names and Blood in the Buffyverse [1] In Joss Whedon’s Buffy the Vampire Slayer (1997-2003) and Angel (1999- 2004), words are not something to be taken lightly. A word read out of place can set a book on fire (“Superstar” 4.17) or send a person to a hell dimension (“Belonging” A2.19); a poorly performed spell can turn mortal enemies into soppy lovebirds (“Something Blue” 4.9); a word in a prophecy might mean “to live” or “to die” or both (“To Shanshu in L.A.” A1.22). -

1; Iya WEEKLY

Platinum Blonde - more than just a pretty -faced rock trio (Page 5) Volume 39 No. 23 February 11, 1984 $1.00 :1;1; iyAWEEKLY . Virgin Canada becomes hotti Toronto: Virgin Records Canada, headed Canac by Bob Muir as President, moves into the You I fifth month flying its own banner and has become one of the hottest labels in the Cultu country. action THE PROMISE CONTINUES.... Contributing to the success of the label by th has been Culture Club with their albums of th4 Basil', Kissing To Be Clever and Colour By Num- bers. Also a major contributor is the break- W. out of the UB40 album, Labour Of Love, first ; boosted by the reggae group's cover of the forth Watch for: old Neil Diamond '60s hit, Red Red Wine. sampl "Over100,000 Colour By Numbers also t albums were shipped in the first ten days band' -the new Images In Vogue video of 1984 alone," said Muir. "The last Ulle40 Tt album only did about 13,000 here. Now, The' albun ... with Labour Of Love, we have the first gold Lust for Love album outside of Europe, and the success ships here is opening doors in the U.S. The record and c; broke in Calgary and Edmonton and started Al -Darkroom's tour (with the Payola$) spreading." Colour By Numbers has just surpassed quintuple platinum status in Canada which Ca] ...Feb. 17-29 represents 500,000 units sold, which took Va. about 16 weeks. The album was boosted and a new remixed 7" and 12" of San Paku by the hit singles Church Of The Poison Toros Mind, now well over gold, and the latest based single, Karma Chameleon, now well over of Ca the platinum mark in less than ten weeks prom This - a newsingle by Ann Mortifee of release. -

Adrian Grenier

PETRICE JONES (00:01): Somewhere deep in the basin of the Pacific and network of hydrophones crawls across the ocean floor. These hydrophones of relics from the cold war built by the us Navy to monitor the movements of enemy submarines underwater. In 1992, off the coast of Whidbey Island in Puget sound, they recorded something else. WHALE SOUNDS (00:29): [inaudible] PETRICE JONES (00:30): A haunting ghostly sound that post onto the graph pages at a frequency of 52, it was a whale for technicians, struggled to believe what they were seeing on paper. The vocalizations looked like they belong to a blue whale, except the blue whales call usually registers around 15 to 20 huts. So 52 was completely off the charts. So far off that no other way. I was known to communicate that pitch. As far as anyone knew, it was the only recording and the only whale of its kind, the technicians named him 52 blue, 52 blues identity remained a mystery for 30 years. No one knows where he came from. What kind of whale he is, what he looks like, or if he even is Hey, but the tail of the loneliest whale is not gone. Unheard here at lonely whale, we've been inspired by 52. The whale who dares to call out at his own frequency. 52 Hertz is a podcast for the unique voices working in ocean conservation. These are the entrepreneurs, activists, and youth leaders going against the current to rethink our approach to plastics and environmentalism on a global scale in this, our first episode of our first podcast ever, I speak with lonely whale co founder, Adrian ganja by the plastic crisis in our oceans, our power to turn the tide by going against it. -

Soap Opera Digest 2021 Publishing Calendar

2021 MEDIA KIT Soap Opera Digest 2021 Publishing Calendar Issue # Issue Date On Sale Date Close Date Materials Due Date 1 01/04/21 12/25/20 11/27/20 12/04/20 2 01/11/21 01/01/21 12/04/20 12/11/20 3 01/18/21 01/08/21 12/11/20 12/18/20 4 01/25/21 01/15/21 12/18/20 12/25/20 5 02/01/21 01/22/21 12/25/20 01/01/21 6 02/08/21 01/29/21 01/01/21 01/08/21 7 02/15/21 02/05/21 01/08/21 01/15/21 8 02/22/21 02/12/21 01/15/21 01/22/21 9 03/01/21 02/19/21 01/22/21 01/29/21 10 03/08/21 02/26/21 01/29/21 02/05/21 11 03/15/21 03/05/21 02/05/21 02/12/21 12 03/22/21 03/12/21 02/12/21 02/19/21 13 03/29/21 03/19/21 02/19/21 02/26/21 14 04/05/21 03/26/21 02/26/21 03/05/21 15 04/12/21 04/02/21 03/05/21 03/12/21 16 04/19/21 04/09/21 03/12/21 03/19/21 17 04/26/21 04/16/21 03/19/21 03/26/21 18 05/03/21 04/23/21 03/26/21 04/02/21 19 05/10/21 04/30/21 04/02/21 04/09/21 20 05/17/21 05/07/21 04/09/21 04/16/21 21 05/24/21 05/14/21 04/16/21 04/23/21 22 05/31/21 05/21/21 04/23/21 04/30/21 23 06/07/21 05/28/21 04/30/21 05/07/21 24 06/14/21 06/04/21 05/07/21 05/14/21 25 06/21/21 06/11/21 05/14/21 05/21/21 26 06/28/21 06/18/21 05/21/21 05/28/21 27 07/05/21 06/25/21 05/28/21 06/04/21 28 07/12/21 07/02/21 06/04/21 06/11/21 29 07/19/21 07/09/21 06/11/21 06/18/21 30 07/26/21 07/16/21 06/18/21 06/25/21 31 08/02/21 07/23/21 06/25/21 07/02/21 32 08/09/21 07/30/21 07/02/21 07/09/21 33 08/16/21 08/06/21 07/09/21 07/16/21 34 08/23/21 08/13/21 07/16/21 07/23/21 35 08/30/21 08/20/21 07/23/21 07/30/21 36 09/06/21 08/27/21 07/30/21 08/06/21 37 09/13/21 09/03/21 08/06/21 08/13/21 38 09/20/21