The History of Wake Forest College, Volume IV, 1943-1967

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Full List of Signatures Is Here

IAVA Recipient: Secretary Mattis Letter: Greetings, First, thank you for your service and sacrifice and for your incredible leadership that so many in the military and veteran community have experienced and respect. As you know, more than 1.5 million veterans have have educated themselves with the Post-9/11 GI Bill, and almost 70% of Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America (IAVA) members have used or transferred this benefit to a dependent. It could very well be the most transformative federal benefit created. The new restriction on Post-9/11 GI Bill transferability to only those with less than 16 years of service is a completely unnecessary reduction of this critical benefit, and it will ultimately hurt our military recruitment and readiness. In a time of war, it remains enormously important to recruit and retain qualified servicemembers, especially with an ever-decreasing pool of eligible recruits. For years, IAVA has been at the forefront of this fight. We led the effort to establish this benefit in 2008 and we have successfully defended it in recent years. We cannot allow our GI Bill to be dismantled or abused. This is why I am standing with my fellow IAVA members to respectfully request that you reverse this counterproductive policy change that creates barriers to access to these transformative benefits. The GI Bill has been earned by millions of men and women on the battlefield and around the world and it should not be subjected to arbitrary restrictions that limit its use. Again, thank you for your leadership and I ask that you take action now to reverse this decision. -

Men's Basketball Coaching Records

MEN’S BASKETBALL COACHING RECORDS Overall Coaching Records 2 NCAA Division I Coaching Records 4 Coaching Honors 31 Division II Coaching Records 36 Division III Coaching Records 39 ALL-DIVISIONS COACHING RECORDS Some of the won-lost records included in this coaches section Coach (Alma Mater), Schools, Tenure Yrs. WonLost Pct. have been adjusted because of action by the NCAA Committee 26. Thad Matta (Butler 1990) Butler 2001, Xavier 15 401 125 .762 on Infractions to forfeit or vacate particular regular-season 2002-04, Ohio St. 2005-15* games or vacate particular NCAA tournament games. 27. Torchy Clark (Marquette 1951) UCF 1970-83 14 268 84 .761 28. Vic Bubas (North Carolina St. 1951) Duke 10 213 67 .761 1960-69 COACHES BY WINNING PERCENT- 29. Ron Niekamp (Miami (OH) 1972) Findlay 26 589 185 .761 1986-11 AGE 30. Ray Harper (Ky. Wesleyan 1985) Ky. 15 316 99 .761 Wesleyan 1997-05, Oklahoma City 2006- (This list includes all coaches with a minimum 10 head coaching 08, Western Ky. 2012-15* Seasons at NCAA schools regardless of classification.) 31. Mike Jones (Mississippi Col. 1975) Mississippi 16 330 104 .760 Col. 1989-02, 07-08 32. Lucias Mitchell (Jackson St. 1956) Alabama 15 325 103 .759 Coach (Alma Mater), Schools, Tenure Yrs. WonLost Pct. St. 1964-67, Kentucky St. 1968-75, Norfolk 1. Jim Crutchfield (West Virginia 1978) West 11 300 53 .850 St. 1979-81 Liberty 2005-15* 33. Harry Fisher (Columbia 1905) Fordham 1905, 16 189 60 .759 2. Clair Bee (Waynesburg 1925) Rider 1929-31, 21 412 88 .824 Columbia 1907, Army West Point 1907, LIU Brooklyn 1932-43, 46-51 Columbia 1908-10, St. -

Appendix File Anes 1988‐1992 Merged Senate File

Version 03 Codebook ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ CODEBOOK APPENDIX FILE ANES 1988‐1992 MERGED SENATE FILE USER NOTE: Much of his file has been converted to electronic format via OCR scanning. As a result, the user is advised that some errors in character recognition may have resulted within the text. MASTER CODES: The following master codes follow in this order: PARTY‐CANDIDATE MASTER CODE CAMPAIGN ISSUES MASTER CODES CONGRESSIONAL LEADERSHIP CODE ELECTIVE OFFICE CODE RELIGIOUS PREFERENCE MASTER CODE SENATOR NAMES CODES CAMPAIGN MANAGERS AND POLLSTERS CAMPAIGN CONTENT CODES HOUSE CANDIDATES CANDIDATE CODES >> VII. MASTER CODES ‐ Survey Variables >> VII.A. Party/Candidate ('Likes/Dislikes') ? PARTY‐CANDIDATE MASTER CODE PARTY ONLY ‐‐ PEOPLE WITHIN PARTY 0001 Johnson 0002 Kennedy, John; JFK 0003 Kennedy, Robert; RFK 0004 Kennedy, Edward; "Ted" 0005 Kennedy, NA which 0006 Truman 0007 Roosevelt; "FDR" 0008 McGovern 0009 Carter 0010 Mondale 0011 McCarthy, Eugene 0012 Humphrey 0013 Muskie 0014 Dukakis, Michael 0015 Wallace 0016 Jackson, Jesse 0017 Clinton, Bill 0031 Eisenhower; Ike 0032 Nixon 0034 Rockefeller 0035 Reagan 0036 Ford 0037 Bush 0038 Connally 0039 Kissinger 0040 McCarthy, Joseph 0041 Buchanan, Pat 0051 Other national party figures (Senators, Congressman, etc.) 0052 Local party figures (city, state, etc.) 0053 Good/Young/Experienced leaders; like whole ticket 0054 Bad/Old/Inexperienced leaders; dislike whole ticket 0055 Reference to vice‐presidential candidate ? Make 0097 Other people within party reasons Card PARTY ONLY ‐‐ PARTY CHARACTERISTICS 0101 Traditional Democratic voter: always been a Democrat; just a Democrat; never been a Republican; just couldn't vote Republican 0102 Traditional Republican voter: always been a Republican; just a Republican; never been a Democrat; just couldn't vote Democratic 0111 Positive, personal, affective terms applied to party‐‐good/nice people; patriotic; etc. -

36-49 Records, All-Time Roster, Duke Stuff.Indd

CCareerareer OOffensiveffensive RRecordsecords Games Played Games Started At-Bats Runs Scored 240 Jeff Becker 1996-2000 240 Jeff Becker 1996-2000 947 Jeff Becker 1996-2000 232 Jeff Becker 1996-2000 222 Kevin Kelly 1999-2002 221 Kevin Kelly 1999-2002 859 Ryan Jackson 1991-94 203 Frankie Chiou 1994-97 219 Michael Fletcher 1995-98 218 Frankie Chiou 1994-97 846 Kevin Kelly 1999-2002 200 Vaughn Schill 1997-99 219 Troy Caradonna 2000-03 217 Troy Caradonna 2000-03 825 Javier Socorro 2003-06 187 Ryan Jackson 1991-94 218 Frankie Chiou 1994-97 215 Ryan Jackson 1991-94 821 Troy Caradonna 2000-03 187 Quinton McCracken 1989-92 215 Ryan Jackson 1991-94 214 Javier Socorro 2003-06 806 Mike King 1993-96 179 Mike King 1993-96 214 Adam Murray 2003-06 212 Adam Murray 2003-06 804 Frankie Chiou 1994-97 173 Jeff Piscorik 1992-95 214 Javier Socorro 2006-06 209 Gregg Maluchnik 1995-98 780 Adam Murray 2003-06 172 Gregg Maluchnik 1995-98 214 Cass Hopkins 1990-93 208 Mike King 1993-96 765 Michael Fletcher 1995-98 172 Sean McNally 1991-94 212 Mike King 1993-96 205 Cass Hopkins 1990-93 759 Gregg Maluchnik 1995-98 158 Scott Pinoni 1992-94 209 Gregg Maluchnik 1995-98 198 Michael Fletcher 1995-98 756 Sean McNally 1991-94 151 Michael Fletcher 1995-98 207 Sean McNally 1991-94 198 Sean McNally 1991-94 754 Quinton McCracken 1989-92 150 Kevin Kelly 1999-2002 205 Jeff Piscorik 1992-95 193 Quinton McCracken 1989-92 703 Cass Hopkins 1990-93 146 Luis Duarte 1992-95 199 Luis Duarte 1992-95 190 Jeff Piscorik 1992-95 689 Vaughn Schill 1997-99 142 Mark Militello 1981-84 194 Bryan -

![Download: Wake Forest: the University Magazine [May 1981]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8324/download-wake-forest-the-university-magazine-may-1981-198324.webp)

Download: Wake Forest: the University Magazine [May 1981]

-Wake Forest-- The University Magazine Frank Johnson celebrates o victory over VIrginia after his lost go me at home in Me morial Coliseum. ]ohmon scored sixteen of his In the lost lwenly-flve minutes of the game. County Leaders Named RJR Gift Inaugurates Sesquicentennial Campaign in Forsyth R.j . Reynolds Industries Inc. has given The Forsyth County drive that the Reynolds gift Alumni Assoaation; Lyons Gray, vice president, $1.5 million to the University's $17.5 million launched is headed by john W. Burress m, president Intercontinental Consultants Corporation and hus Sesquicentennial Campaign. The gift is the largest of J W. Burress, Inc. Serving with him are eight vice band of Constance Fraser Gray, member of the the Reynolda Campus of the University has chairmen: University Board of Visitors; L. Glenn Orr Jr ., received from a corporation. (Reynolds made a F Hudnall Christopher Jr .. Executive Vice- President. president, Forsyth Bank and Trust Co.; joseph H $1.5 million gift in 1977 to the Bowman Gray Rj Re ynold~ Tobacco Co.: George W. Crone Jr. , General Parrish ]r., prestdent, Parrish Tire Co. Richard School of Medicine on the Hawthorne Campus.) manager Container Corporation of America: E. Stockton, president, Norman Stockton. Inc.; ilnd Joel ]. Paul Stiehl, chairman and chief executive officer Lawrence Davis of Womble. CJrlyl~ ~mdbridge and E. Weston )r ('5Q, MBA '73), president, Hanes Dye of the company. announced the gift February 18, Rice. attorneys: William K Davi' () [) e>b, Ot Bell. Davi and Finishmg Co. 1981 at a press conference which also marked the and Pitt and president ot the \\'a!..t: F, r. -

EXTENSIONS of REMARKS 16201 for the Commercialized Production of Syn H.R

June 22, 1979 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS 16201 for the commercialized production of syn H.R. 13: Mr. BOWEN, Mr. BROYHILL, Mr. AMENDMENTS thetic fossil fuels; jointly, to the Commit CAMPBELL, Mr. CHAPPELL, :Mr. RoBERT W. tees on Banking, Finance and Urban Af DANIEL, JR., Mr. DASCHLE, Mr. DoUGHERTY, Under clause 6 of the rule XXIII, pro fairs and Interstate and Foreign Commerce. Mrs. FENWICK, Mr. FITHIAN, Mr. GUYER, Mr. posed amendments were submitted as By Mr. PEPPER: HINSON, Mr. JEFFORDS, Mr. LEE, Mr. MYERS Of follows: H.R. 4589. A bill to authorize reduced fa.ires Indiana, Mr. NICHOLS, Mr. RINALDO, Mr. H.R. 3930 for the elderly and handicapped on the THOMAS, Mr. TRIBLE, and Mr. WAMPLER. By Mr. HEFTEL: Nation's railroads; to the Committee on In H.R 154: M!l'. BIAGGI. -Page 4, beginning on line 25, strike out terstate and Foreign Commerce. H.R.1979: Mr. ERDAHL, and Mr. RINALDO. "500,000 barrels per day crude oil equivalent H.R. 4590. A bill to remove the coinsur H.R. 3539: Mr. BARNARD. of synthetic fuels and synthetic chemical ance amount which a patient has to pay H.R. 3721: Mr. HYDE, Mr. MITCHELL of New feedstocks not later than five years after under part A of the medic9.l'e program for the effective date of this section." and in inpatient hospital services after such serv York, Mr. RoBINSON, Mr. DouGHERTY, and Mr. DORNAN. sert in lieu thereof "5,000,000 barrels per ices have been furnished to such patient for day crude oil equivalent of synthetic fuels 60 days during a spell of illness; to the H.R. -

CAROLINAS KEY CLUBS As of 4 14 2018

2018-2019 CAROLINAS KEY CLUBS AS OF 4/14/2018 DIVISION REGION KEY CLUB/SCHOOL NAME SPONSORING KIWANIS CLUB 01 01 AC REYNOLDS ASHEVILLE 01 01 CHARLES D OWEN HIGH SCHOOL BLACK MOUNTAIN-SWANNANOA 01 01 ENKA HIGH SCHOOL ASHEVILLE 01 01 ERWIN HIGH SCHOOL ASHEVILLE 01 01 MCDOWELL EARLY COLLEGE MARION 01 01 PISGAH HIGH SCHOOL WAYNESVILLE 01 01 TUSCOLA HIGH SCHOOL WAYNESVILLE 02 01 CHASE HIGH SCHOOL FOREST CITY 02 01 EAST HENDERSON HIGH SCHOOL HENDERSONVILLE 02 01 EAST RUTHERFORD HIGH SCHOOL FOREST CITY 02 01 HENDERSON COUNTY EARLY COLLEGE HENDERSONVILLE 02 01 HENDERSONVILLE HIGH SCHOOL HENDERSONVILLE 02 01 NORTH HENDERSON HIGH SCHOOL HENDERSONVILLE 02 01 POLK COUNTY HIGH SCHOOL TRYON 02 01 WEST HENDERSON HIGH SCHOOL HENDERSONVILLE 03 01 AVERY HIGH SCHOOL BANNER ELK 03 01 EAST WILKES HIGH SCHOOL NORTH WILKESBORO 03 01 FREEDOM HIGH SCHOOL MORGANTON 03 01 HIBRITEN HIGH SCHOOL LENIOR 03 01 MITCHELL HIGH SCHOOL SPRUCE PINE 03 01 NORTH WILKES HIGH SCHOOL NORTH WILKESBORO 03 01 PATTON HIGH SCHOOL MORGANTON 03 01 WATAUGA HIGH SCHOOL BOONE 03 01 WEST WILKES HIGH SCHOOL NORTH WILKESBORO 03 01 WILKES CENTRAL HIGH SCHOOL NORTH WILKESBORO 03 01 WILKES EARLY COLLEGE HIGH SCHOOL NORTH WILKESBORO 05A 03 DAVIE HIGH SCHOOL TWIN CITY, WINSTON SALEM 05A 03 EAST ROWAN HIGH SCHOOL SALISBURY 05A 03 JESSE C CARSON HIGH SCHOOL SALISBURY 05A 03 MOUNT TABOR HIGH SCHOOL TWIN CITY, WINSTON SALEM 05A 03 NORTH ROWAN HIGH SCHOOL SALISBURY 05A 03 RONALD REAGAN HIGH SCHOOL TWIN CITY, WINSTON SALEM 05A 03 SALISBURY HIGH SCHOOL SALISBURY 05A 03 SOUTH IREDELL HIGH SCHOOL STATESVILLE -

The Contributions of Professor D. Barry Lumsden to Teacher Development in Higher Education

Academic Leadership: The Online Journal Volume 8 Article 6 Issue 1 Winter 2010 1-1-2010 A True Underdog: The onC tributions of Professor D. Barry Lumsden to Teacher Development in Higher Education Rick Lumadue Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.fhsu.edu/alj Part of the Educational Leadership Commons, Higher Education Commons, and the Teacher Education and Professional Development Commons Recommended Citation Lumadue, Rick (2010) "A True Underdog: The onC tributions of Professor D. Barry Lumsden to Teacher Development in Higher Education," Academic Leadership: The Online Journal: Vol. 8 : Iss. 1 , Article 6. Available at: https://scholars.fhsu.edu/alj/vol8/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FHSU Scholars Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Academic Leadership: The Online Journal by an authorized editor of FHSU Scholars Repository. academicleadership.org http://www.academicleadership.org/428/a_true_underdog_the_co ntributions_of_professor_d_barry_lumsden_to_teacher_developm ent_in_higher_education/ Academic Leadership Journal People love stories about real-life underdogs who overcome insurmountable odds to achieve success. This article chronicles one such underdog in the truest sense of the word. As one of the privileged students to have had the opportunity to study under Dr. Lumsden, this paper is written as a tribute to the contributions of D. Barry Lumsden to the contemporary practice of Higher Education. Lumsden has developed numerous teachers in the field of higher education. The information for this paper was obtained through personal interviews with Lumsden, correspondence with his former students and firsthand experiences as his student. Lumsden and I maintain a great friendship and I continue to be mentored by him both professionally and personally. -

REPORT CARD Study Year 2005-2006

REPORT CARD Study Year 2005-2006 September 2007 This publication is Wake Technical Community College's report card on the college's performance in meeting these prescribed twelve standards Critical Success Factor established by the state. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction .................................................................1 Goals ............................................................................3 Summary Report on Performance Measures .........27 Community Services.................................................31 Partnerships ..............................................................35 INTRODUCTION In 1999, the North Carolina State Board of Community Colleges and the North Carolina General Assembly adopted a set of twelve performance measures. Beginning with the 2000-2001 academic year these twelve performance standards will be used to measure the accountability level of each of the fifty- eight institutions in the North Carolina Community College System (NCCCS) and a portion (two percent) of their operating budgets (58 community colleges) will be directly linked to six (measures one through five are permanently set by the General Assembly, the sixth measure is identified by each college) of these benchmark measures (Progress of Basic Skills Students; Passing Rates for Licensure and Certification Examinations; Goal Completion of Program Completers; Employment Status of Graduates; Performance of College Transfer Students; and Employer Satisfaction with Graduates). 1. Progress of Basic Skills Students 2. Passing -

Mississippi Education Association Convention Program Mississippi Education Association

University of Mississippi eGrove Mississippi Education Collection General Special Collections 1968 Mississippi Education Association Convention Program Mississippi Education Association Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/ms_educ Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Mississippi Education Association, "Mississippi Education Association Convention Program" (1968). Mississippi Education Collection. 16. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/ms_educ/16 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the General Special Collections at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mississippi Education Collection by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Official Program 82nd Annual Convention MISSISSIPPI EDUCATION ASSOCIATION March 13-14-15, 1968 Jackson, Mississippi Program Cover b y : Gilbert Ford, Hiatt-Ford Photographers, Ja ckson 1 Officers, 1967-1968 INDEX President: W. L. Rigby ___________ . ___________________________ Gulfport President-Elect: Mrs. Elise Curtis ____________________________ Utica Officers & Board of Directors ___________ 00 ___________________________ 3 Executive Secretary: C. A. Johnson _____________________ Jackson Mr. Rigby ____________________________________________ 00 __________________________ 4 Welcome from the President _00 _____________________________________ 5 Board of Directors Convention Committees ____________________________________________ 00 6-7 Emma Ruth Corban-Immediate MEA Section Chairmen ______ 00 _______________________________________ -

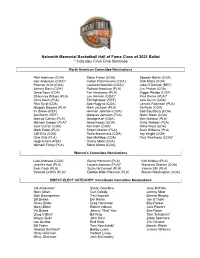

Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame Class of 2021 Ballot * Indicates First-Time Nominee

Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame Class of 2021 Ballot * Indicates First-Time Nominee North American Committee Nominations Rick Adelman (COA) Steve Fisher (COA) Speedy Morris (COA) Ken Anderson (COA)* Cotton Fitzsimmons (COA) Dick Motta (COA) Fletcher Arritt (COA) Leonard Hamilton (COA)* Jake O’Donnell (REF) Johnny Bach (COA) Richard Hamilton (PLA) Jim Phelan (COA) Gene Bess (COA) Tim Hardaway (PLA) Digger Phelps (COA) Chauncey Billups (PLA) Lou Henson (COA)* Paul Pierce (PLA)* Chris Bosh (PLA) Ed Hightower (REF) Jere Quinn (COA) Rick Byrd (COA) Bob Huggins (COA) Lamont Robinson (PLA) Muggsy Bogues (PLA) Mark Jackson (PLA) Bo Ryan (COA) Irv Brown (REF) Herman Johnson (COA) Bob Saulsbury (COA) Jim Burch (REF) Marques Johnson (PLA) Norm Sloan (COA) Marcus Camby (PLA) George Karl (COA) Ben Wallace (PLA) Michael Cooper (PLA)* Gene Keady (COA) Chris Webber (PLA) Jack Curran (COA) Ken Kern (COA) Willie West (COA) Mark Eaton (PLA) Shawn Marion (PLA) Buck Williams (PLA) Cliff Ellis (COA) Rollie Massimino (COA) Jay Wright (COA) Dale Ellis (PLA) Bob McKillop (COA) Paul Westhead (COA)* Hugh Evans (REF) Danny Miles (COA) Michael Finley (PLA) Steve Moore (COA) Women’s Committee Nominations Leta Andrews (COA) Becky Hammon (PLA) Kim Mulkey (PLA) Jennifer Azzi (PLA) Lauren Jackson (PLA)* Marianne Stanley (COA) Swin Cash (PLA) Suzie McConnell (PLA) Valerie Still (PLA) Yolanda Griffith (PLA)* Debbie Miller-Palmore (PLA) Marian Washington (COA) DIRECT-ELECT CATEGORY: Contributor Committee Nominations Val Ackerman* Simon Gourdine Jerry McHale Marv -

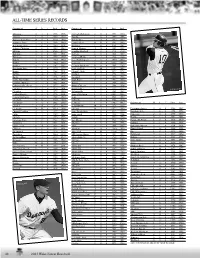

All-Time Series Records

ALL-TIME SERIES RECORDS Opponent W L T First Last Opponent W L T First Last Alabama 0 1 0 1996 1996 Fairleigh Dickinson 2 0 0 1994 1994 Albany 1 0 0 2002 2002 Florida 1 6 0 1957 1998 Appalachian State 26 9 0 1970 2002 Florida Int’l 1 4 0 1987 1988 Arkansas State 1 0 0 1989 1989 Florida State 16 53 0 1962 2002 Armstrong State 2 0 0 1989 1991 Fordham 1 0 0 1981 1981 Atlantic Christian 1 0 0 1954 1954 Francis Marion 4 0 0 1983 1987 Auburn 0 2 0 1966 1999 Franklin-Marshall 1 1 0 1971 1972 Ball State 1 0 0 1991 1991 Furman 6 1 0 1961 1997 Baltimore 2 0 0 1977 1977 Gardner-Webb 4 2 0 1984 1988 Baptist 1 1 0 1980 1980 Geo.Washington 2 0 0 1970 2002 Baylor 0 1 0 1989 1989 Georgia 8 15 0 1963 2002 Bradley 0 1 0 1987 1987 Georgia Southern 14 8 0 1961 1989 Brockport State 1 0 0 1975 1975 Georgia Tech 28 44 1 1957 2002 Brown 5 0 0 1968 1991 Glenville State 2 0 0 1977 1978 Buffalo 7 4 0 1982 1997 Guilford 15 3 0 1974 1990 Butler 1 0 0 1996 1996 Hartford 4 1 0 1990 1995 Cal St. Northridge 1 0 0 1992 1992 High Point 12 8 0 1973 2002 Cal Santa Barbara 0 1 0 1991 1991 Illinois 1 1 0 1998 1998 California (Pa.) State 2 1 0 1977 1987 Illinois-Chicago 1 1 0 1994 1994 Campbell 22 9 0 1976 2001 Indiana (Pa.) 1 0 0 1972 1972 Jeff Ruziecki Catawba 14 5 0 1973 1986 Jacksonville 2 1 0 1961 1969 Central Florida 1 2 0 1996 2001 James Madison 1 0 0 2001 2001 Central Michigan 1 1 0 1989 1989 Kent 11 3 0 1961 1997 Charlotte 23 18 1 1980 2002 Lafayette 2 0 0 1964 1964 Cincinnati 3 0 0 2002 2002 LeMoyne 1 0 0 1982 1982 Opponent W L T First Last Citadel 3 4 0 1977 1997