The Promotion of Solar Energy in the Israeli Desert Itay Fischhendler, Dror Boymel & Maxwell T Boykoff

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exhibitors Catalogue

Exhibitors Catalogue ADAMA Makhteshim Agronet portal A CEO: Shlomi Nachum CEO: ayelet oron Marketing Manager: Danny Zahor Marketing Manager: ayelet oron A.B.Seed Sales Field of Activity: One of the world’s Field of Activity: agronet portal CEO: Yuval Ben Shushan (Sales leading agrochemical companies. Address: cfar saaba Manager) An importer and distributor of crop Tel: 504009974 Marketing Manager: Tali Edri protection products and agricultural Fax: +972 72-2128787 Field of Activity: Marketing and selling seeds. E-mail: [email protected] seeds in Israel Address: 1st. Golan st. Airport city Website: www.agronet.co.il Address: 2 Hanegev, Lod Tel: 3 6577577, Fax: +972 3 6032310 Tel: 3 9733661 E-mail: [email protected] AMIT SOLAR Fax: +972 3 9733663 Website: www.adama.com/mcw CEO: igal Reuveni E-mail: [email protected] Marketing Manager: Goldstein Amit Website: www.seminis.co.il Agam Ner / Greefa Field of Activity: A company that CEO: Nir Gilad manages and executes projects in the Aclartech Marketing Manager: Natan Gilad, fields of infrastructure, electricity, solar, CEO: Avi Schwartzer Agriculture Devision Manager wind and communications. Marketing Manager: Avi Schwartzer Field of Activity: Sele and service of Establishment of large, commercial, Field of Activity: AclarTech’s mobile sorting and packaging equipment and domestic net counter systems. application, AclaroMeter, monitors and for fruits and vegetablespalletizing Address: Betzet 87 analyzes fruit quality, ripeness and packages of vegetablesIndustrial Tel: 4-9875966 freshness.Address: Moshe Lerer 19 / 7 diesel enginesSpecial equipment Fax: +972 4-9875955 Nes Ziona Israel upon requestAddress: 19 Weizmann E-mail: [email protected] Tel: 545660850 Givatayim, Israel Website: http://www.amitsunsolar.co.il/ Fax: +972 545660850 Tel: 50-8485022 E-mail: [email protected] Fax: +972 3-6990160 Avihar /Nftali farm Website: www.aclartech.com E-mail: [email protected] hatzeva.arava Website: none CEO: Avihar Giora Agrolan Marketing Manager: Naftali Fraddy CEO: Yehuda Glikman AgriQuality Ltd. -

Cohen V. Facebook

Case 1:16-cv-04453-NGG-LB Document 1-1 Filed 08/10/16 Page 1 of 113 PageID #: 70 EXHIBIT A Case 1:16-cv-04453-NGG-LB Document 1-1 Filed 08/10/16 Page 2 of 113 PageID #: 71 ~ SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK COUNTY OF KINGS --------------------------------------------------------------------- Index No: Pa~1, / l 5 RICHARD LAKIN; and additional plaintiffs listed on Rider A, Date Purchased: 10/~(~C~/ 15 Plaintiffs designate Kings County as the Plaintiffs, place of trial. The basis of vcnue is CPLR 503(a), -against- SUMMONS FA=CEBOOK, Q Plaintiffs residcs at: Defendant. c/o Shurat HaDin — Israel Law Center, 10 ---------------------------------------------- X flata'as Street, Ramat Gan, Israel TO THE ABOVE NAMED DEFENDANTS: YOU ARE HEREBY SUMMONED to answer the complaint in this action and to serve a copy of your answer, on the plaintiff s Attorneys within 20 days afi.er the service of this summons, exclusive ot'the day of service (or within 30 days aftcr scrvice is complctc if this summons is not personally delivered to you within the State ofNew York) and to file a copy of your answer with the Clerk of the above-named Court; and in case of your failure to appear or answer, judgment will be taken against you by default for the relief demanded in the complaint. Dated: Brooklyn, New York Octobcr 26, 2015 Yours, THE BERKMAN LAW OFFICE, LLC 0~ ~ ~ Atull~,r~.Jor he~+f zti/r ~ S`~ a by: 7 +~ '/ ° O' Q _.J Robert J. 111 Livingston Street, Suite 1928 Brooklyn, New York 11201 (718) 855-3627 ZECIA L 1 STS \~ NITSANA DARSHAN-LEITNER & CO Nitsana Darshan-Leitner . -

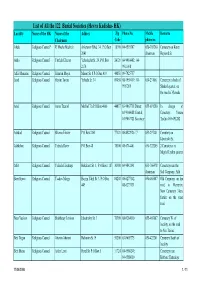

List of All the 122 Burial Societies (Hevra Kadisha- HK) Locality Name of the HK Name of the Addres Zip Phone No

List of All the 122 Burial Societies (Hevra Kadisha- HK) Locality Name of the HK Name of the Addres Zip Phone No. Mobile Remarks Chairman Code phone no. Afula Religious Council* R' Moshe Mashiah Arlozorov Blvd. 34, P.O.Box 18100 04-6593507 050-303260 Cemetery on Keren 2041 chairman Hayesod St. Akko Religious Council Yitzhak Elharar Yehoshafat St. 29, P.O.Box 24121 04-9910402; 04- 2174 9911098 Alfei Menashe Religious Council Shim'on Moyal Manor St. 8 P.O.Box 419 44851 09-7925757 Arad Religious Council Hayim Tovim Yehuda St. 34 89058 08-9959419; 08- 050-231061 Cemetery in back of 9957269 Shaked quarter, on the road to Massada Ariel Religious Council Amos Tzuriel Mish'ol 7/a P.O.Box 4066 44837 03-9067718 Direct; 055-691280 In charge of 03-9366088 Central; Cemetery: Yoram 03-9067721 Secretary Tzefira 055-691282 Ashdod Religious Council Shlomo Eliezer P.O.Box 2161 77121 08-8522926 / 7 053-297401 Cemetery on Jabotinski St. Ashkelon Religious Council Yehuda Raviv P.O.Box 48 78100 08-6714401 050-322205 2 Cemeteries in Migdal Tzafon quarter Atlit Religious Council Yehuda Elmakays Hakalanit St. 1, P.O.Box 1187 30300 04-9842141 053-766478 Cemetery near the chairman Salt Company, Atlit Beer Sheva Religious Council Yaakov Margy Hayim Yahil St. 3, P.O.Box 84208 08-6277142, 050-465887 Old Cemetery on the 449 08-6273131 road to Harzerim; New Cemetery 3 km. further on the same road Beer Yaakov Religious Council Shabbetay Levison Jabotinsky St. 3 70300 08-9284010 055-465887 Cemetery W. -

Israeli Settler-Colonialism and Apartheid Over Palestine

Metula Majdal Shams Abil al-Qamh ! Neve Ativ Misgav Am Yuval Nimrod ! Al-Sanbariyya Kfar Gil'adi ZZ Ma'ayan Baruch ! MM Ein Qiniyye ! Dan Sanir Israeli Settler-Colonialism and Apartheid over Palestine Al-Sanbariyya DD Al-Manshiyya ! Dafna ! Mas'ada ! Al-Khisas Khan Al-Duwayr ¥ Huneen Al-Zuq Al-tahtani ! ! ! HaGoshrim Al Mansoura Margaliot Kiryat !Shmona al-Madahel G GLazGzaGza!G G G ! Al Khalsa Buq'ata Ethnic Cleansing and Population Transfer (1948 – present) G GBeGit GHil!GlelG Gal-'A!bisiyya Menara G G G G G G G Odem Qaytiyya Kfar Szold In order to establish exclusive Jewish-Israeli control, Israel has carried out a policy of population transfer. By fostering Jewish G G G!G SG dGe NG ehemia G AGl-NGa'iGmaG G G immigration and settlements, and forcibly displacing indigenous Palestinians, Israel has changed the demographic composition of the ¥ G G G G G G G !Al-Dawwara El-Rom G G G G G GAmG ir country. Today, 70% of Palestinians are refugees and internally displaced persons and approximately one half of the people are in exile G G GKfGar GB!lGumG G G G G G G SGalihiya abroad. None of them are allowed to return. L e b a n o n Shamir U N D ii s e n g a g e m e n tt O b s e rr v a tt ii o n F o rr c e s Al Buwayziyya! NeoG t MG oGrdGecGhaGi G ! G G G!G G G G Al-Hamra G GAl-GZawG iyGa G G ! Khiyam Al Walid Forcible transfer of Palestinians continues until today, mainly in the Southern District (Beersheba Region), the historical, coastal G G G G GAl-GMuGftskhara ! G G G G G G G Lehavot HaBashan Palestinian towns ("mixed towns") and in the occupied West Bank, in particular in the Israeli-prolaimed “greater Jerusalem”, the Jordan G G G G G G G Merom Golan Yiftah G G G G G G G Valley and the southern Hebron District. -

2015 Hartoch Noam 1068300

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ A History of the Syrian Air Force 1947-1967 Hartoch, Noam Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 25. Sep. 2021 KING’S COLLEGE LONDON FACULTY OF ARTS AND HUMANITIES Dissertation A History of the Syrian Air Force 1947-1967 By Noam Hartoch Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy July 2015 1 Abstract Shortly after gaining independence in the summer of 1945, the Syrian government set about to form the Syrian Air Force (SAF). -

Abstract and Table of Contents

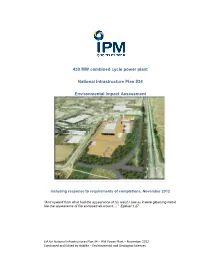

430 MW combined cycle power plant National Infrastructure Plan #34 Environmental Impact Assessment Including response to requirements of completions, November 2012 "And upward from what had the appearance of his waist I saw as it were gleaming metal, like the appearance of fire enclosed all around…." Ezekiel 1:27 EIA for National Infrastructures Plan 34 – IPM Power Plant – November 2012 Conducted and Edited by AdaMa – Environmental and Geological Sciences About the project - National Infrastructure Plan No. 43 ("The plan") designates land and determines building instructions for the construction of a power plant with a capacity of about 430 MW. The power plant ("The plant") will be fuel burned by natural gas. Initiating the station and declaring it as a national infrastructure is the result of the Ministry of National Infrastructure and The Ministry of Environmental Protection Policy. According to the Ministry of Infrastructure's policy, 20% of production capacity in the country will be from power plants owned by private producers, which will be duly licensed by the state. According to the Ministry of Environment Policy, power plant will be located in areas designated for industry. The first version of the EIA was submitted in September 2011. The EIA submitted in January 2012 contains additions required by the environmental consultant of the National Infrastructure Committee. The current version is submitted after completing the conditions for deposit as provided by the permit of the environmental consultant of the National Infrastructure Committee. The proposed station is on a lot the size of approximately 60 "dunam" (unit for measuring land area, about 1/4 acre) in the Beer Tuvia industrial zone, tangent to road 40. -

Ministry of Education Culture and Sport Economics and Budgeting Administration

State of Israel Ministry of Education Culture and Sport Economics and Budgeting Administration MINISTRY OF EDUCATION CULTURE AND SPORT FACTS AND FIGURES Written and adapted by: Dalia Sprinzak, Ehud Bar, Yedidia Segev, Daniel Levi-Mazloum Jerusalem, August 2004 Photographs of schools and works of art – from the collection of the School Building Design Division, Ministry of Education Culture and Sport. Page 13 "Ramot Yitzhak" Lower Secondary School, Nesher. Architects: Dina Amar and Abraham Koriel. Page 17 “Shoham” Secondary School. Environmental sculpture project: “Four Trees”. Design: Architects Michael Mikulsky and Ayelet Kal. Page 19 Dror Comprehensive School, Lev Hasharon. Architect: David Nofar. Page 23 Ma’ayan School, Yavneh. "World of the Sea" schoolyard environment, with play and study equipment. Design: Bruce Levin, Architect. Page 25 "Reut" School, Hod Hasharon. Zoological park. Design: Feder Architects. Page 27 MASKAL, Zichron Ya’akov. Hands-on and therapeutic garden for learning the alphabet. Design: Tav Architects. Page 31 "Amal Lakia" Secondary School, Lakia. Ceramic sculpted wall. Artist: Nili Oron. Page 38 Ironi Aleph School, Modi’in. Sculpture at school entrance gate: "Drummer." Artist: Ofra Cymbalista. Page 40 State-Religious School Aleph – "Dorot," Modi’in. Architect: Aviram Rosenberg. Page 76 "Harel" Upper Secondary School, Mevaseret Zion. Design: Architects Esther Levi and Marianne Cohen. Page 97 State Religious School for Sciences, Ashkelon. Architect: David Nofar. Page 105 Ironi Aleph Comprehensive School, Ashkelon. Schoolyard sculpture project: "The Musicians." Artist: Ofra Cymbalista. Page 113 "Amal Lakia" Secondary School, Lakia. Central Patio. Design: Architect Ya’akov Kessler. Page 116 "Hatzav" Lower Secondary School, Alfei Menashe. Environmental sculpture project: "Leaves," and seating area. -

List of All the 122 Burial Societies (Hevra Kadisha- HK) in the State of Israel Locality Name of the HK Name of the Chairman Address Zip Phone No

List of All the 122 Burial Societies (Hevra Kadisha- HK) in the State of Israel Locality Name of the HK Name of the Chairman Address Zip Phone No. Mobile phone no. Remarks Code Afula Religious Council* R' Moshe Mashiah Arlozorov Blvd. 34, 18100 04-6593507 050-303260 chairman Cemetery on Keren Hayesod St. P.O.Box 2041 Akko Religious Council Yitzhak Elharar Yehoshafat St. 29, 24121 04-9910402; P.O.Box 2174 04-9911098 Alfei Menashe Religious Council Shim'on Moyal Manor St. 8 44851 09-7925757 P.O.Box 419 Arad Religious Council Hayim Tovim Yehuda St. 34 89058 08-9959419; 050-231061 Cemetery in back of Shaked 08-9957269 quarter, on the road to Massada Ariel Religious Council Amos Tzuriel Mish'ol 7/a 44837 03-9067718 Direct; 055-691280 In charge of Cemetery: P.O.Box 4066 03-9366088 Central; Yoram Tzefira 055-691282 03-9067721 Secretary Ashdod Religious Council Shlomo Eliezer P.O.Box 2161 77121 08-8522926 / 7 053-297401 Cemetery on Jabotinski St. Ashkelon Religious Council Yehuda Raviv P.O.Box 48 78100 08-6714401 050-322205 2 Cemeteries in Migdal Tzafon quarter Atlit Religious Council Yehuda Elmakays Hakalanit St. 1, 30300 04-9842141 053-766478 chairman Cemetery near the Salt Company, P.O.Box 1187 Atlit Beer Sheva Religious Council Yaakov Margy Hayim Yahil St. 3, 84208 08-6277142, 050-465887 Old Cemetery on the road to P.O.Box 449 08-6273131 Harzerim; New Cemetery 3 km. further on the same road Beer Yaakov Religious Council Shabbetay Levison Jabotinsky St. 3 70300 08-9284010 055-465887 Cemetery W. -

The London School of Economics and Political Science

The London School of Economics and Political Science ‘Muddling Through’ Hasbara: Israeli Government Communications Policy, 1966 – 1975 Jonathan Cummings A thesis submitted to the Department of International History of the London School of Economics and Political Science for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, December 2012 ‘In this and like communities, public sentiment is everything. With public sentiment, nothing can fail; without it nothing can succeed. Consequently, he who moulds public sentiment goes deeper than he who enacts statutes or pronounces decisions. He makes statutes and decisions possible or impossible to be executed. Abraham Lincoln ‘By persuading others, we convince ourselves’ Junius ii Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. iii Abstract This thesis is the history of an intense period of Israeli attempts to address the issue of how the state should communicate its national image, particularly on the international stage. Between 1966 and 1975, the Eshkol, Meir and Rabin governments invested far more time and energy in the management of Israel’s international image than the governments before or after. -

Israel: 'Secret' Defense Ministry Database Reveals Full Settlement Construction

Israel: 'Secret' Defense Ministry Database Reveals Full Settlement Construction GMP20090319738001 Israel ‐‐ OSC Summary in Hebrew 30 Jan 09 Left‐of‐center, independent daily of record Tel Aviv Haaretz.com in English on 30 January carried the referent item with a link to a 195‐page PDF file in Hebrew of a "secret Defense Ministry database on illegal construction in the territories" translated herein. Quotation marks as published; passages in italics appear in red in the original. Settlement Name: AVNEY HEFETZ [Precious Stones] Name source: Isaiah, 54:12 "And all your walls precious stones," as well as the name of the nearby Khirbat al‐Hafitza. Settlement type and organizational affiliation: Communal settlement, Amana Coordinate: 1575.1880 Number of residents: 1,254. District: Tulkarm. Municipality: Shomron Regional Council Cabinet Resolutions: 1. 861 (HT/70) ‐‐ 2 August 1984 ‐‐ Approving the construction of an urban neighborhood named Avney Hefetz, east of Tulkarm. "We hereby decide, based on the government settlement policy, to approve the construction of Avney Hefetz, an urban neighborhood: "1. The neighborhood will be built at coordinate 1575.1880, some 5 km east of Tulkarm. "2. Population: Planned, designated for 1,000 families. "3. The plot: Some 1,300 dunams of state lands of which 500 dunams are undisputed and some 400 dunams are private acquisitions in various stages. "4. Employment: Industry and services in the settlement and its vicinity. "5. Regional system: The settlement will belong to the Shomron Regional Council and will be part of the Eynav‐Shavey Shomron bloc. "6.(1) Initiator and localizing body: The Fund for Land Redemption ‐ Settlement Planning and Development Ltd. -

Aalders, Gerard, 373 Abayat, Atef, 555 Abd Rabbo, Yasir, 526, 527, 542

Index Aalders, Gerard, 373 Aisenstadt, Andre, 303 Abayat, Atef, 555 Aish Hatorah, 705 Abd Rabbo, Yasir, 526, 527, 542, 550 Akron Jewish News, 732 Abecassis, Eliette, 342 Albanel, Christine, 338 Abel, Lionel, 737 Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Abella, Irving, 291 695 Abraham Fund, 658 Alberstein, Chava, 430 Abraham, Spencer, 154 Albert, Shea, 519 Abraham, Yonason, 315 Albright, Madeleine, 573 Abramson, Samuel, 454 Aleksandrova, V., 628M Abse, Danny, 319 Aleksei II, Patriarch, 482 Abu Hanud, Muhammad, 542, 543, Alemu, Yafet, 599 556 ALEPH: Alliance for Jewish Renewal, Abu Qibeh, Khalil, 548 674 Abu Zeidah, Nassar, 563 Alfasi, Yosef, 561 Abutbul, Hadas, 566 Algemeiner Journal, 728 Academy for Jewish Religion, 685 Almagor, J., 622M Ackerman, Gary, 168, 206 Al-Maralh, Nabil, 278 Adams, Philip, 493 Al-Marayati, Salam, 181 Adel, Allan, 284 Almog, Oz, 321 Adenauer, Konrad, 13, 13M, 14, 14M, Alpert, Michael, 321 15,16,18,21 Alpert, Patricia, 303 Adler, Emanuel, 296 Alpha Epsilon Pi Fraternity, 697 Adler, Larry, 323, 737 Altshuler, Mordechai, 623n, 627M Afn Shvel, 728 Alvan, Esther, 561 Agbogbe, Damien, 436 Aly, Gotz, 419-20 Agenda: Jewish Education, 728 Am Kolel Judaic Resource Center, Agudath Israel of America, 114, 117, 674 118,121, 155, 184,233,235,673 Amar, Yair, 567 Agudath Israel World Organization, Amato, Giuliano, 378 15M, 16, 51 n, 674 Amaudruz, Gaston-Armand, 399 Aharonishky, Shlomo, 598 Ambrose, Tom, 321 Aherae, Bertie, 539 AMC Cancer Research Center, 699 Ahmad, Sheikh, 380 Amcha for Tsedakah, 699 783 784 / AMERICAN JEWISH YEAR -

Cohen V. Facebook, Inc. Complaint

Case 1:16-cv-04453-NGG-LB Document 1-1 Filed 08/10/16 Page 1 of 113 PageID #: 70 EXHIBIT A Case 1:16-cv-04453-NGG-LB Document 1-1 Filed 08/10/16 Page 2 of 113 PageID #: 71 ~ SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK COUNTY OF KINGS --------------------------------------------------------------------- Index No: Pa~1, / l 5 RICHARD LAKIN; and additional plaintiffs listed on Rider A, Date Purchased: 10/~(~C~/ 15 Plaintiffs designate Kings County as the Plaintiffs, place of trial. The basis of vcnue is CPLR 503(a), -against- SUMMONS FA=CEBOOK, Q Plaintiffs residcs at: Defendant. c/o Shurat HaDin — Israel Law Center, 10 ---------------------------------------------- X flata'as Street, Ramat Gan, Israel TO THE ABOVE NAMED DEFENDANTS: YOU ARE HEREBY SUMMONED to answer the complaint in this action and to serve a copy of your answer, on the plaintiff s Attorneys within 20 days afi.er the service of this summons, exclusive ot'the day of service (or within 30 days aftcr scrvice is complctc if this summons is not personally delivered to you within the State ofNew York) and to file a copy of your answer with the Clerk of the above-named Court; and in case of your failure to appear or answer, judgment will be taken against you by default for the relief demanded in the complaint. Dated: Brooklyn, New York Octobcr 26, 2015 Yours, THE BERKMAN LAW OFFICE, LLC 0~ ~ ~ Atull~,r~.Jor he~+f zti/r ~ S`~ a by: 7 +~ '/ ° O' Q _.J Robert J. 111 Livingston Street, Suite 1928 Brooklyn, New York 11201 (718) 855-3627 ZECIA L 1 STS \~ NITSANA DARSHAN-LEITNER & CO Nitsana Darshan-Leitner .