Dissertation Final Copy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comic Strips and the American Family, 1930-1960 Dahnya Nicole Hernandez Pitzer College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Pitzer Senior Theses Pitzer Student Scholarship 2014 Funny Pages: Comic Strips and the American Family, 1930-1960 Dahnya Nicole Hernandez Pitzer College Recommended Citation Hernandez, Dahnya Nicole, "Funny Pages: Comic Strips and the American Family, 1930-1960" (2014). Pitzer Senior Theses. Paper 60. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/pitzer_theses/60 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Pitzer Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pitzer Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FUNNY PAGES COMIC STRIPS AND THE AMERICAN FAMILY, 1930-1960 BY DAHNYA HERNANDEZ-ROACH SUBMITTED TO PITZER COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE BACHELOR OF ARTS DEGREE FIRST READER: PROFESSOR BILL ANTHES SECOND READER: PROFESSOR MATTHEW DELMONT APRIL 25, 2014 0 Table of Contents Acknowledgements...........................................................................................................................................2 Introduction.........................................................................................................................................................3 Chapter One: Blondie.....................................................................................................................................18 Chapter Two: Little Orphan Annie............................................................................................................35 -

Woman War Correspondent,” 1846-1945

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Carolina Digital Repository CONDITIONS OF ACCEPTANCE: THE UNITED STATES MILITARY, THE PRESS, AND THE “WOMAN WAR CORRESPONDENT,” 1846-1945 Carolyn M. Edy A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Journalism and Mass Communication. Chapel Hill 2012 Approved by: Jean Folkerts W. Fitzhugh Brundage Jacquelyn Dowd Hall Frank E. Fee, Jr. Barbara Friedman ©2012 Carolyn Martindale Edy ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii Abstract CAROLYN M. EDY: Conditions of Acceptance: The United States Military, the Press, and the “Woman War Correspondent,” 1846-1945 (Under the direction of Jean Folkerts) This dissertation chronicles the history of American women who worked as war correspondents through the end of World War II, demonstrating the ways the military, the press, and women themselves constructed categories for war reporting that promoted and prevented women’s access to war: the “war correspondent,” who covered war-related news, and the “woman war correspondent,” who covered the woman’s angle of war. As the first study to examine these concepts, from their emergence in the press through their use in military directives, this dissertation relies upon a variety of sources to consider the roles and influences, not only of the women who worked as war correspondents but of the individuals and institutions surrounding their work. Nineteenth and early 20th century newspapers continually featured the woman war correspondent—often as the first or only of her kind, even as they wrote about more than sixty such women by 1914. -

Screwball Syll

Webster University FLST 3160: Topics in Film Studies: Screwball Comedy Instructor: Dr. Diane Carson, Ph.D. Email: [email protected] COURSE DESCRIPTION: This course focuses on classic screwball comedies from the 1930s and 40s. Films studied include It Happened One Night, Bringing Up Baby, The Awful Truth, and The Lady Eve. Thematic as well as technical elements will be analyzed. Actors include Katharine Hepburn, Cary Grant, Clark Gable, and Barbara Stanwyck. Class involves lectures, discussions, written analysis, and in-class screenings. COURSE OBJECTIVES: The purpose of this course is to analyze and inform students about the screwball comedy genre. By the end of the semester, students should have: 1. An understanding of the basic elements of screwball comedies including important elements expressed cinematically in illustrative selections from noteworthy screwball comedy directors. 2. An ability to analyze music and sound, editing (montage), performance, camera movement and angle, composition (mise-en-scene), screenwriting and directing and to understand how these technical elements contribute to the screwball comedy film under scrutiny. 3. An ability to apply various approaches to comic film analysis, including consideration of aesthetic elements, sociocultural critiques, and psychoanalytic methodology. 4. An understanding of diverse directorial styles and the effect upon the viewer. 5. An ability to analyze different kinds of screwball comedies from the earliest example in 1934 through the genre’s development into the early 40s. 6. Acquaintance with several classic screwball comedies and what makes them unique. 7. An ability to think critically about responses to the screwball comedy genre and to have insight into the films under scrutiny. -

Women by County

WOMEN BY COUNTY Albany County Maria Van Rensselaer, 1645-1688 (Colonial and Revolutionary Eras) “Mother” Ann Lee, 1736-1784 (Faith Leaders) Harriet Myers, 1807-1865 (Abolition and Suffrage) Columbia County Margaret Beekman Livingston, 1724-1800 (Entrepreneurs) “Mother” Ann Lee, 1736-1784 (Faith Leaders) Elizabeth Freeman, “Mumbet,” 1742-1829 (Abolition and Suffrage) Janet Livingston Montgomery, 1743-1828 (Colonial & Revolutionary War Eras) Flavia Marinda Bristol, 1824-1918 (Entrepreneurs) Ida Helen Ogilvie, 1874-1963 (STEM) Edna St. Vincent Millay, 1892-1950 (The Arts) Ella Fitzgerald, 1917-1996 (The Arts) Lillian “Pete” Campbell, 1929-2017 (Reformers, Activists, and Trailblazers) Dutchess County Cathryna Rombout Brett, 1687-1763 (Entrepreneurs) Janet Livingston Montgomery, 1743-1828 (Colonial & Revolutionary War Eras) Sybil Ludington, 1761-1839 (Colonial & Revolutionary War Eras) Lucretia Mott, 1793-1880 (Abolition and Suffrage) Maria Mitchell, 1818-1889 (STEM) Antonia Maury, 1866-1952 (STEM) Beatrix Farrand, 1872-1959 (STEM) Eleanor Roosevelt, 1884-1962 (Reformers, Activists, and Trailblazers) Inez Milholland, 1886-1916 (Abolition and Suffrage) Edna St. Vincent Millay, 1892-1950 (The Arts) Dorothy Day, 1897-1980 (Faith Leaders) Elizabeth “Lee” Miller, 1907-1977 (Reformers, Activists, and Trailblazers) Jane Bolin, 1908-2007 (Reformers, Activists, and Trailblazers) Katharine Graham, 1917-2001(Entrepreneurs) Frances “Franny” Reese, 1917-2003 (Reformers, Activists, and Trailblazers) Raquel Rabinovich, b. 1929 (The Arts) Greene County Sybil Ludington, 1761-1839 (Colonial and Revolutionary War Eras) Candace Wheeler, 1827-1923 (The Arts) Margaret Newton Van Cott, 1830-1914 (Faith Leaders) Elizabeth Cochrane Seaman “Nellie Bly,” 1864-1922 (Reformers, Activists…) Ruth Franckling Reynolds, 1918-2007 (Reformers, Activists, and Trailblazers) Orange County Jane Colden, 1724-1760 (STEM) Margaret “Capt. -

Pdf Study Guide

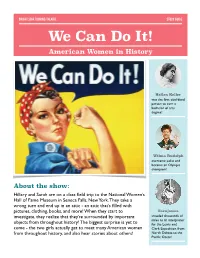

BRIGHT STAR TOURING THEATRE STUDY GUIDE We Can Do It! American Women in History Hellen Keller was the first deaf-blind person to earn a bachelor of arts degree! Wilma Rudolph overcame polio and became an Olympic champion! About the show: Hillary and Sarah are on a class field trip to the National Women’s Hall of Fame Museum in Seneca Falls, New York. They take a wrong turn and end up in an attic - an attic that’s filled with pictures, clothing, books, and more! When they start to Sacajawea investigate, they realize that they’re surrounded by important traveled thousands of miles as an interpreter objects from throughout history! The biggest surprise is yet to for the Lewis and come - the two girls actually get to meet many American women Clark Expedition, from from throughout history, and also hear stories about others! North Dakota to the ! Pacific Ocean! Classroom Activities Questions for Discussion: 1. In 1848, Elizabeth Cady Stanton wrote that “all men and women are created equal.” What do you think she meant by that? What are some of the things that women were not allowed to do at that time? 2. Women have been brave, smart, and creative to achieve their goals. What did Deborah Sampson do that was brave? Smart? Creative? What about Sacajawea? What about Nelly Bly? 3. Though the play talked about many American Women, who are others that the play didn’t cover who have been important in our history? 4. What new information did you learn from watching the play that you didn’t know before? Map it! Scene Study! This activity incorporates social This activity incorporates creative thinking, research, studies and geography!! writing, and performance! 1. -

Modern Womanhood

MODERNIZING AMERICA, 1889-1920 Modern Womanhood Resource: Life Story: Elizabeth Cochrane, aka Nellie Bly (1864-1922) Nellie Bly Nellie Bly, c. 1890. Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division Washington, D.C. © Women and the American Story 2021 Page 1 of 8 MODERNIZING AMERICA, 1889-1920 Modern Womanhood Round the World with Nellie Bly McLoughlin Bros., Round the World with Nellie Bly, 1890. Collection of the New-York Historical Society. © Women and the American Story 2021 Page 2 of 8 MODERNIZING AMERICA, 1889-1920 Modern Womanhood Elizabeth Cochran was born on May 5, 1864 in Cochran’s Mills, Pennsylvania. The town was founded by her father, Judge Michael Cochran. Elizabeth had fourteen siblings. Her father had ten children from his first marriage and five children from his second marriage to Elizabeth’s mother, Mary Jane Kennedy. Michael Cochran’s rise from mill worker to mill owner to judge meant his family lived very comfortably. Unfortunately, he died when Elizabeth was only six years old and his fortune was divided among his many children, leaving Elizabeth’s mother and her children with a small fraction of the wealth they once enjoyed. Elizabeth’s mother soon remarried, but quickly divorced her second husband because of abuse, and relocated the family to Pittsburgh. Elizabeth knew that she would need to support herself financially. At the age of 15, she enrolled in the State Normal School in Indiana, Pennsylvania, and an added an “e” to her last name to sound more distinguished. Her plan was to graduate and find a position as a teacher. However, after only a year and a half, Elizabeth ran out of money and could no longer afford the tuition. -

Example of an Authorship Review

Student’s Name Independent Honors English Authorship Review Fall 2020 Ernest Hemingway (1899-1961) Born in Oak Park, Illinois, on July 21, 1899, Ernest Hemingway grew up to be one of the most notable writers in 20th Century America, winning the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1953 for his novella, The Old Man and the Sea. His writing career began on his high school newspaper, Trapeze and Tabula, and his interest in journalism continued after graduation when he took a job as a reporter at the Kansas City Star. In 1918, 19-year-old Ernest served as an ambulance driver for the Red Cross in Italy but was subsequently injured in an explosion. He convalesced in a hospital in Milan and started a flirting relationship with a nurse named Agnes. This brief romance, along with his experience as an ambulance driver in WWI, served as the source material for his third novel, A Farewell to Arms. Back in Chicago, Ernest took a job writing for the Toronto Star and met his first wife, Hadley Richardson. The couple soon joined a growing number of literary expatriates - like F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald, and Ezra Pound - who relocated to Paris after the war. They were a part of the Lost Generation. While in Paris, Ernest and Hadley traveled with their friends frequently to Spain to watch the bull fights, thus giving him source material for his first published novel, The Sun Also Rises. Ernest and Hadley had one son, but the couple did not last on account of Ernest’s affair with Pauline Pfeiffer. -

Ivens Magazine Blz18tm37.Pdf

basin, Ivens yells: ‘We will shoot this scene again in half an June 15th – June 22nd 1956 Damme, Belgium June 25th - July 12th 1956, Mulde, Germany Gérard Philipe and Joris Ivens, hour! There is too much smoke, the horses do not cavort Part of the film crew travelled to Flanders, Bruges, in order On June 25th, Gérard Philipe and Joris Ivens arrived at film clips in East Germany enough and the bridge explosion is not as spectacular as it to add some authentic elements of the local colour to the Tempelhof airport in East Berlin together with the French from Les aventures de Till should be’ … The Dutch journalists could not believe what film. The shots of the actual canal and the opening scene in crew, after the press and hundreds of fans had been waiting l’Espiègle (The Adventures they saw. Their national history was being turned into a the dunes and the countryside were filmed there. And the there for hours. ‘Plenty of teen-agers came to see the ‘jeune of Till Eulenspiegel), 1956. film in the French Riviera by a‘ modest Dutchman’. They scene, in which the city of Damme goes up in flames. Mean- premier’ of the French film’, is what a journalist wrote, who © DEFA Stiftung wanted to know from Ivens how the collaboration was go- while, Ivens became continuously more concerned about was surprised that the fans were so hysterical. ing. ‘Gérard and I, we each direct certain fragments. He, for the direction in which the film was heading. ‘Attention que The last scenes in the GDR were all about the large-scaled instance, works a lot with the French actors, and does the l’action comique et dynamique ne domine pas, ou ébaufe la battles on the banks of the Scheldt between the Spaniards, work that requires the input of an experienced feature film situation serieuse.’, he wrote.24 After three months, he final- on the one hand, and the rebellions of the Geuzen army and man; I am responsible for the outside shoots and the action ly cut the knot and told DEFA that he wanted to back out of the mercenary army of the Prince of Orange on the other. -

Mean Streets: Death and Disfiguration in Hawks's Scarface

Mean Streets: Death and Disfiguration in Hawks's Scarface ASBJØRN GRØNSTAD Consider this paradox: in Howard Hawks' Scarface, The Shame of the Nation, violence is virtually all-encompassing, yet it is a film from an era before American movies really got violent. There are no graphic close-ups of bullet wounds or slow-motion dissection of agonized faces and bodies, only a series of abrupt, almost perfunctory liquidations seemingly devoid of the heat and passion that characterize the deaths of the spastic Lyle Gotch in The Wild Bunch or the anguished Mr. Orange, slowly bleeding to death, in Reservoir Dogs. Nonetheless, as Bernie Cook correctly points out, Scarface is the most violent of all the gangster films of the eatly 1930s cycle (1999: 545).' Hawks's camera desists from examining the anatomy of the punctured flesh and the extended convulsions of corporeality in transition. The film's approach, conforming to the period style of ptc-Bonnie and Clyde depictions of violence, is understated, euphemistic, in its attention to the particulars of what Mark Ledbetter sees as "narrative scarring" (1996: x). It would not be illegitimate to describe the form of violence in Scarface as discreet, were it not for the fact that appraisals of the aesthetics of violence are primarily a question of kinds, and not degrees. In Hawks's film, as we shall see, violence orchestrates the deep structure of the narrative logic, yielding an hysterical form of plotting that hovers between the impulse toward self- effacement and the desire to advance an ethics of emasculation. Scarface is a film in which violence completely takes over the narrative, becoming both its vehicle and its determination. -

English Language and Composition!

Welcome to English Language and Composition! We are so excited for what next year has in store in AP Lang. Contained in this packet is all the information you need to know about your summer reading homework, and what you can expect in August. This course, due to our non-fiction and rhetorical focus, is structured very differently than the English classes you might be used to, but we know you are up for the challenge. Don’t get overwhelmed. Most of what’s contained here are resources to help you, not the assignments themselves. You got this! It’s going to be a great year! To give you some context, according to College Board, “The AP English Language and Composition course focuses on the development and revision of evidence-based analytic and argumentative writing and the rhetorical analysis of non-fiction texts.” Sounds fun, right!? One of the best ways that we can prepare you for the class over the summer is to make sure we have some common language when it comes to the art of persuasion. That’s why our summer reading selection is chapters 1-18 of Thank You for Arguing Third Edition by Jay Heinrichs. (ISBN #: 978-0804189934) The book perfectly “front loads” fundamental information essential to understanding the complexities of rhetoric. Please make sure you purchase the third edition (Publication Date: 2017). This book has been specifically revised with the AP Lang student in mind. Heinrichs consistently uses “pop culture” and engaging entertainment mediums to make rhetoric applicable to students’ daily lives. He references historical rhetoric, both old and new, in order to reveal how rhetorical communication shapes the course of history. -

Sob Sisters: the Image of the Female Journalist in Popular Culture

SOB SISTERS: THE IMAGE OF THE FEMALE JOURNALIST IN POPULAR CULTURE By Joe Saltzman Director, Image of the Journalist in Popular Culture (IJPC) Joe Saltzman 2003 The Image of the Female Journalist in Popular Culture revolves around a dichotomy never quite resolved. The female journalist faces an ongoing dilemma: How to incorporate the masculine traits of journalism essential for success – being aggressive, self-reliant, curious, tough, ambitious, cynical, cocky, unsympathetic – while still being the woman society would like her to be – compassionate, caring, loving, maternal, sympathetic. Female reporters and editors in fiction have fought to overcome this central contradiction throughout the 20th century and are still fighting the battle today. Not much early fiction featured newswomen. Before 1880, there were few newspaperwomen and only about five novels written about them.1 Some real-life newswomen were well known – Margaret Fuller, Nelly Bly (Elizabeth Cochrane), Annie Laurie (Winifred Sweet or Winifred Black), Jennie June (Jane Cunningham Croly) – but most female journalists were not permitted to write on important topics. Front-page assignments, politics, finance and sports were not usually given to women. Top newsroom positions were for men only. Novels and short stories of Victorian America offered the prejudices of the day: Newspaper work, like most work outside the home, was for men only. Women were supposed to marry, have children and stay home. To become a journalist, women had to have a good excuse – perhaps a dead husband and starving children. Those who did write articles from home kept it to themselves. Few admitted they wrote for a living. Women who tried to have both marriage and a career flirted with disaster.2 The professional woman of the period was usually educated, single, and middle or upper class. -

Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell

Copyrights sought (Albert) Basil (Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell) Filson Young (Alexander) Forbes Hendry (Alexander) Frederick Whyte (Alfred Hubert) Roy Fedden (Alfred) Alistair Cooke (Alfred) Guy Garrod (Alfred) James Hawkey (Archibald) Berkeley Milne (Archibald) David Stirling (Archibald) Havergal Downes-Shaw (Arthur) Berriedale Keith (Arthur) Beverley Baxter (Arthur) Cecil Tyrrell Beck (Arthur) Clive Morrison-Bell (Arthur) Hugh (Elsdale) Molson (Arthur) Mervyn Stockwood (Arthur) Paul Boissier, Harrow Heraldry Committee & Harrow School (Arthur) Trevor Dawson (Arwyn) Lynn Ungoed-Thomas (Basil Arthur) John Peto (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin & New Statesman (Borlasse Elward) Wyndham Childs (Cecil Frederick) Nevil Macready (Cecil George) Graham Hayman (Charles Edward) Howard Vincent (Charles Henry) Collins Baker (Charles) Alexander Harris (Charles) Cyril Clarke (Charles) Edgar Wood (Charles) Edward Troup (Charles) Frederick (Howard) Gough (Charles) Michael Duff (Charles) Philip Fothergill (Charles) Philip Fothergill, Liberal National Organisation, N-E Warwickshire Liberal Association & Rt Hon Charles Albert McCurdy (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett & World Review of Reviews (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Colin) Mark Patrick (Crwfurd) Wilfrid Griffin Eady (Cyril) Berkeley Ormerod (Cyril) Desmond Keeling (Cyril) George Toogood (Cyril) Kenneth Bird (David) Euan Wallace (Davies) Evan Bedford (Denis Duncan)