Modern Womanhood

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women by County

WOMEN BY COUNTY Albany County Maria Van Rensselaer, 1645-1688 (Colonial and Revolutionary Eras) “Mother” Ann Lee, 1736-1784 (Faith Leaders) Harriet Myers, 1807-1865 (Abolition and Suffrage) Columbia County Margaret Beekman Livingston, 1724-1800 (Entrepreneurs) “Mother” Ann Lee, 1736-1784 (Faith Leaders) Elizabeth Freeman, “Mumbet,” 1742-1829 (Abolition and Suffrage) Janet Livingston Montgomery, 1743-1828 (Colonial & Revolutionary War Eras) Flavia Marinda Bristol, 1824-1918 (Entrepreneurs) Ida Helen Ogilvie, 1874-1963 (STEM) Edna St. Vincent Millay, 1892-1950 (The Arts) Ella Fitzgerald, 1917-1996 (The Arts) Lillian “Pete” Campbell, 1929-2017 (Reformers, Activists, and Trailblazers) Dutchess County Cathryna Rombout Brett, 1687-1763 (Entrepreneurs) Janet Livingston Montgomery, 1743-1828 (Colonial & Revolutionary War Eras) Sybil Ludington, 1761-1839 (Colonial & Revolutionary War Eras) Lucretia Mott, 1793-1880 (Abolition and Suffrage) Maria Mitchell, 1818-1889 (STEM) Antonia Maury, 1866-1952 (STEM) Beatrix Farrand, 1872-1959 (STEM) Eleanor Roosevelt, 1884-1962 (Reformers, Activists, and Trailblazers) Inez Milholland, 1886-1916 (Abolition and Suffrage) Edna St. Vincent Millay, 1892-1950 (The Arts) Dorothy Day, 1897-1980 (Faith Leaders) Elizabeth “Lee” Miller, 1907-1977 (Reformers, Activists, and Trailblazers) Jane Bolin, 1908-2007 (Reformers, Activists, and Trailblazers) Katharine Graham, 1917-2001(Entrepreneurs) Frances “Franny” Reese, 1917-2003 (Reformers, Activists, and Trailblazers) Raquel Rabinovich, b. 1929 (The Arts) Greene County Sybil Ludington, 1761-1839 (Colonial and Revolutionary War Eras) Candace Wheeler, 1827-1923 (The Arts) Margaret Newton Van Cott, 1830-1914 (Faith Leaders) Elizabeth Cochrane Seaman “Nellie Bly,” 1864-1922 (Reformers, Activists…) Ruth Franckling Reynolds, 1918-2007 (Reformers, Activists, and Trailblazers) Orange County Jane Colden, 1724-1760 (STEM) Margaret “Capt. -

Pdf Study Guide

BRIGHT STAR TOURING THEATRE STUDY GUIDE We Can Do It! American Women in History Hellen Keller was the first deaf-blind person to earn a bachelor of arts degree! Wilma Rudolph overcame polio and became an Olympic champion! About the show: Hillary and Sarah are on a class field trip to the National Women’s Hall of Fame Museum in Seneca Falls, New York. They take a wrong turn and end up in an attic - an attic that’s filled with pictures, clothing, books, and more! When they start to Sacajawea investigate, they realize that they’re surrounded by important traveled thousands of miles as an interpreter objects from throughout history! The biggest surprise is yet to for the Lewis and come - the two girls actually get to meet many American women Clark Expedition, from from throughout history, and also hear stories about others! North Dakota to the ! Pacific Ocean! Classroom Activities Questions for Discussion: 1. In 1848, Elizabeth Cady Stanton wrote that “all men and women are created equal.” What do you think she meant by that? What are some of the things that women were not allowed to do at that time? 2. Women have been brave, smart, and creative to achieve their goals. What did Deborah Sampson do that was brave? Smart? Creative? What about Sacajawea? What about Nelly Bly? 3. Though the play talked about many American Women, who are others that the play didn’t cover who have been important in our history? 4. What new information did you learn from watching the play that you didn’t know before? Map it! Scene Study! This activity incorporates social This activity incorporates creative thinking, research, studies and geography!! writing, and performance! 1. -

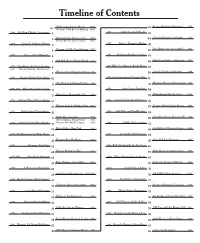

Timeline of Contents

Timeline of Contents Roots of Feminist Movement 1970 p.1 1866 Convention in Albany 1866 42 Women’s 1868 Boston Meeting 1868 1970 Artist Georgia O’Keeffe 1869 1869 Equal Rights Association 2 43 Gain for Women’s Job Rights 1971 3 Elizabeth Cady Stanton at 80 1895 44 Harriet Beecher Stowe, Author 1896 1972 Signs of Change in Media 1906 Susan B. Anthony Tribute 4 45 Equal Rights Amendment OK’d 1972 5 Women at Odds Over Suffrage 1907 46 1972 Shift From People to Politics 1908 Hopes of the Suffragette 6 47 High Court Rules on Abortion 1973 7 400,000 Cheer Suffrage March 1912 48 1973 Billie Jean King vs. Bobby Riggs 1912 Clara Barton, Red Cross Founder 8 49 1913 Harriet Tubman, Abolitionist Schools’ Sex Bias Outlawed 1974 9 Women at the Suffrage Convention 1913 50 1975 First International Women’s Day 1914 Women Making Their Mark 10 51 Margaret Mead, Anthropologist 1978 11 The Woman Sufferage Parade 1915 52 1979 Artist Louise Nevelson 1916-1917 Margaret Sanger on Trial 12 54 Philanthropist Brooke Astor 1980 13 Obstacles to Nationwide Vote 1918 55 1981 Justice Sandra Day O’Connor 1919 Suffrage Wins in House, Senate 14 56 Cosmo’s Helen Gurley Brown 1982 15 Women Gain the Right to Vote 1920 57 1984 Sally Ride and Final Frontier 1921 Birth Control Clinic Opens 16 58 Geraldine Ferraro Runs for VP 1984 17 Nellie Bly, Journalist 1922 60 Annie Oakley, Sharpshooter 1926 NOW: 20 Years Later 1928 Amelia Earhart Over Atlantic 18 Victoria Woodhull’s Legacy 1927 1986 61 Helen Keller’s New York 1932 62 Job Rights in Pregnancy Case 1987 19 1987 Facing the Subtler -

Teacher's Guide

in partnership with TEACHER’S GUIDE pghhistory.org A GALLERY OF HEROES MUSICAL Book, Music and Lyrics written by JASON COLL Major support for the Gallery of Heroes is provided by Massey Charitable Trust, PNC Charitable Trust SCHOOL PROGRAMS AND TOURS Many exciting school programs are available at the History Self-Guided Tours are for teachers who facilitate their Center. Four types of student tours are described below. Please own museum experience. We encourage teachers to tour visit the History Center website at www.heinzhistorycenter.org our building in preparation for their visit. Worksheets or – click on “Education” – to learn more about each tour. For scavenger hunts designed by the teacher are highly each tour theme, you will find a tour overview sheet with a recommended. Self-guided tours are for a maximum of description, objectives, essential questions and a sample of 200 students, pre-kindergarten students through 12th what you might see on the tour. grade. They are one to two hours in length, plus a half hour for lunch, available Monday through Friday, July through February and on Mondays only during March through June. Guided Tours for pre-kindergarten students through 12th These tours feature a museum overview and an introduction grade are one to two hours in length, plus a half hour for by a museum educator and include a map of the History lunch, available Monday through Friday, year-round. Students Center and exhibit directory. will explore many aspects of life in Western Pennsylvania through docent-guided museum learning, investigative questioning, and hands-on discovery. Discussions of daily life Experience Classes provide an opportunity for a class and major events like the British, French, and Indian War, of up to 30 students, pre-kindergarten through 12th grade, Lewis and Clark Expedition, the Civil War, Gilded Age, and to study in-depth with museum experts. -

Learn More About Nellie Bly and Women's History with These Resources

Learn more about Nellie Bly and SCHOOL PROGRAMS AND TOURS in partnership with women’s history with these resources guided museum learning, investigative Self-Guided Tours are for teachers who and an activity. Each class is two to questioning, and hands-on discovery. facilitate their own museum experience. three hours in length, plus a one half Blos, Joan W. Nellie Bly’s Monkey: His Remarkable Story Ehrlich, Elizabeth. Nellie Bly. New York, Chelsea House Discussions of daily life and major We encourage teachers to tour our hour for lunch, and available Monday in his own Words. New York: Morrow Junior Books, 1996. Publishers, 1989. events like the British, French, and building in preparation for their visit. through Friday, July through February. A picture book that tells Nellie Bly’s journey through the A biography of Nellie Bly’s life with excellent images from the Indian War, Lewis and Clark Expedition, Worksheets or scavenger hunts designed Reserve your program at least two eyes of her monkey, McGinty. There is also a short biography different countries that she visited on her around-the-world Many exciting school programs are the Civil War, Gilded Age, and World by the teacher are highly recommended. months in advance in order to schedule at the end. Most suitable for elementary students. trip. Most suitable for middle school students. available at the History Center. Four Wars connect students to the everyday Self-guided tours are for a maximum of with a curator or archivist. pittsburghCLO.org pghhistory.org types of student tours are described and extraordinary lives of local people 200 students, pre-kindergarten students Davidson, Sue. -

Daily Comprehension MAY REM 1110

Daily Comprehension MAY REM 1110 WRITTEN BY: Anne Sattler A TEACHING RESOURCE FROM ©2019, 2015, 2009, 1996 Copyright by Remedia Publications, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. The purchase of this product entitles the individual teacher to reproduce copies for classroom use. The reproduction of any part for an entire school or school system is strictly prohibited. REMEDIA PUBLICATIONS, INC. SCOTTSDALE, AZ This product utilizes innovative strategies and proven methods to improve student learning. The product is based upon reliable research and effective practices that have been replicated in classrooms across the United States. Information regarding the Common Core State Standards this product meets is available at www.rempub.com/standards INTRODUCTION Daily Comprehension is a 12-book series with each volume covering a single month of the year. The format features an “on-this-day-in-history” approach. A short, factual story about a person, place, or event is presented for each day of the month and was chosen because of its particular significance on that certain date. Each story is accompanied by an activity page which tests the student’s comprehension of the article’s content. Activities include questions, crossword puzzles, fill-in-the-blanks, and more. A related research project for each story requires the use of a dictionary, an almanac, an encyclopedia, or an atlas. The books are designed for use in grades 5-12. Readability is on the 3rd-4th grade level. CONTENTS U-2 Incident .......................................................................................................... -

Brave Girls Capaldi, Gina

920.2 Z69c Brave Girls Capaldi, Gina. Red Bird sings: The Story of Zitkala- & Resourceful Females Sa, Native American Author, Musician and Pre-K to Grade 3 Activist Zitkala-Sa finds that she can sing through her mu- sic, but also by writing stories and giving speeches and being an activist for Native American rights. 940.531 Se55r Goldman, Susan Rubin. Irena Sendler and the Children of the Warsaw Ghetto PICTURE BOOKS Recounts the actions of the Polish social worker who, during World War II, defied the Nazis and Funke, Cornelia. Princess Knight risked her life by saving and hiding Jewish children. Violetta, a little princess, secretly teaches herself to be- come the bravest and cleverest knight in the land until she 956.704 W734L must face the king's best knights in a jousting tournament. Winter, Jeanette.The Librarian of Basra: A True Story From Iraq Beaumont, Karen. I Like Myself This true story about a librarian's struggle to save In rhyming text, a little girl expresses confidence and joy in her community's priceless collection of books her uniqueness, no matter her outward appearance or reminds us all how the love of literature and what other people think or say about her. respect for knowledge know no boundaries. Hopkinson, Deborah. Stagecoach Sal PICTURE BOOKS FOR OLDER READERS (in Fiction) When Sal drives a stagecoach alone for the first time to pick up and deliver mail, her mother is afraid she will meet Barry, David. Rajah's Rice: A Mathematical Folktale local outlaw Poetic Pete, but Sal has a trick to keep Pete in from India line. -

Creating a Primary Source Lesson Plan

Women’s Fight for Equality Katy Mullen and Scott Gudgel Stoughton High School London arrest of suffragette. Bain News Service. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, reproduction number LC-DIG-ggbain-10397, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/ggbain.10397/ This unit on women in US History examines gender roles, gender stereotypes, and interpretations of significant events in women’s history. This leads students to discover gender roles in contemporary society. Overview Objectives: Students will: Knowledge • Analyze women’s history and liberation • Analyze the different interpretations of significant historical events Objectives: Students will: Skills • Demonstrate critical thinking skills • Develop writing skills • Collaborative Group work skills Essential “Has the role of women changed in the United States?” Question Recommended 13 50-minute class periods time frame Grade level 10th –12th grade Materials Copies of handouts Personal Laptops for students to work on Missing! PowerPoint. Library time Wisconsin State Standards B.12.2 Analyze primary and secondary sources related to a historical question to evaluate their relevance, make comparisons, integrate new information with prior knowledge, and come to a reasoned conclusion B.12.3 Recall, select, and analyze significant historical periods and the relationships among them B.12.4 Assess the validity of different interpretations of significant historical events B.12.5 Gather various types of historical evidence, including visual and quantitative data, to analyze issues of -

Competing Information in a Free Press

7.2 Competing Information in a Free Press Standard 7.2: Competing Information in a Free Press Give examples of how a free press can provide competing information and views about government and politics. (Massachusetts Curriculum Framework for History and Social Studies) [8.T7.2] A girl holds The Washington Post of Monday, July 21st 1969 stating 'The Eagle Has Landed Two Men Walk on the Moon', by Jack Weir, Public Domain FOCUS QUESTION: How Does a Free Press Provide Competing Information about Government and Politics? Standard 2 looks at how a free press provides information about government and politics to people, both historically and in today's digital age. In many countries around the world, the press is not free and people receive one side only of a story about a topic or issue—the side the government wants published. A free press, by contrast, presents topics so people get wide-ranging and informed perspectives from which they can make up their own minds about what candidates and policies to Building Democracy for All 1 support (explore the site AllSides to see how news is presented differently depending on the platform). Central to free press is the role of investigative journalism that involves the “systematic, in-depth, and original research and reporting,” often including the “unearthing of secrets” (Investigative Journalism: Defining the Craft, Global Investigative Journalism Network). Modules for this Standard Include: 1. INVESTIGATE: History of Newspapers, Then and Now MEDIA LITERACY CONNECTIONS: Examining the News from All Sides 2. UNCOVER: Investigative Journalists: Nellie Bly, Ida Tarbell, Ida B. -

5, Webisode 10

Please note: Each segment in this Webisode has its own Teaching Guide The muckrakers had a good friend in Sam McClure. He founded McClure’s Magazine, which set a new standard for activist journalism and created a new field, investigative journalism. Most important, he hired the best writers he could find: Ida Tarbell, Lincoln Steffens, Jack London, Booth Tarkington, Rudyard Kipling, Stephen Crane, and Willa Cather. Ida Tarbell broke new ground not only in showing what a woman could do in a traditionally male occupation but also in setting a standard for scholarship, fairness, and integrity in the new field of investigative journalism. Her painstakingly researched The History of the Standard Oil Company detailed the illegal tactics used by John D. Rockefeller and led to the 1911 Supreme Court decision to break up the Standard Oil trust. Another female muckraker, Elizabeth Jane Cochrane, got her first job at a newspaper at age nineteen; by twenty-five, she was the most famous woman in the world, known as the daring round-the-world reporter Nellie Bly. Editor Sam McClure and energetic journalists exercised their First Amendment right and used the pen to expose the excesses of the Gilded Age. They gave birth to the field of investigative journalism. Teacher Directions 1. Ask students to predict. • From what you know about the last half of the nineteenth century, what problems might newspaper writers expose? 2. Allow time for student response. 3. Make sure students understand the following points in discussing the question. In the Gilded Age, industry boomed and large corporations grew. -

Nellie Bly and Stunt Journalism: Undercover Exploration to Discover the Truth

Nellie Bly and Stunt Journalism: Undercover Exploration to Discover the Truth Aparna Paul Senior Division Historical Paper Paper Length: 2,497 words 1 “I determined then and there that I would try by every means to make my mission of benefit to my suffering sisters.”1 “[On] the 22d of September I was asked by the World if I could have myself committed to one of the asylums for the insane in New York…[to write a] narrative of the treatment of the patients therein and the methods of management?” This was the proposal presented to Nellie Bly in 1887 as she worked at the New York World under Joseph Pulitzer.2 Bly, a reporter who never shied away from a challenge, accepted one of the first cases of stunt journalism in American media. With her revolutionary articles, Nellie Bly pioneered stunt journalism as a way to expose social injustice. Although she encountered criticism and sexism within her career and in her undercover explorations, Bly’s tactics influenced her contemporaries and inspired future stunt reporters to expose social issues in their own time. In the 1880s, many women journalists occupied a specific role: society reporter. Society reporting was content aimed at women and gossip-mongers; it was the “daily fare spiced with gossip about the rich and famous.”3 Female journalists were so restricted to this role that “many newspapers had only one woman on staff,”4 and the women were rarely allowed to explore other journalistic styles, instead “restricted to [pages]…designed to capitalize on department store advertising aimed at housewives.”5 Society reporting, also known as the women’s section, was considered little more than a gossip column, and “[there] was a sense that any self-respecting 1 Nellie Bly, Ten Days in a Mad-House, (New York City: Ian L. -

The Travels of Nellie Bly and Emma Vely in the Context of Women's

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2020-07-06 The Travels of Nellie Bly and Emma Vely in the Context of Women’s Movement, Colonialism and Female Identity Gilgen, Annika Gilgen, A. (2020). The Travels of Nellie Bly and Emma Vely in the Context of Women’s Movement, Colonialism and Female Identity (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/112279 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY The Travels of Nellie Bly and Emma Vely in the Context of Women’s Movement, Colonialism and Female Identity by Annika Gilgen A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS GRADUATE PROGRAM IN LANGUAGES, LITERATURES, AND CULTURES CALGARY, ALBERTA JULY, 2020 © Annika Gilgen 2020 Abstract This project focuses on the transcultural analysis of travel writings from the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries by the North American journalist Nellie Bly and the German author Emma Vely. It will examine displayed female identity and creations of “Otherness” in their travel writings through the lens of the authors’ positions on women’s rights matters.