Reconceptualizing Superwork for Improved Access to Popular Cultural Objects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

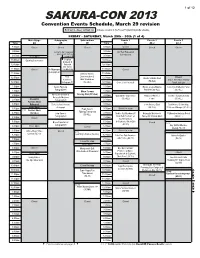

Sakura-Con 2013

1 of 12 SAKURA-CON 2013 Convention Events Schedule, March 29 revision FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 29th - 30th (2 of 4) FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 29th - 30th (3 of 4) FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 29th - 30th (4 of 4) Panels 4 Panels 5 Panels 6 Panels 7 Panels 8 Workshop Karaoke Youth Console Gaming Arcade/Rock Theater 1 Theater 2 Theater 3 FUNimation Theater Anime Music Video Seattle Go Mahjong Miniatures Gaming Roleplaying Gaming Collectible Card Gaming Bold text in a heavy outlined box indicates revisions to the Pocket Programming Guide schedule. 4C-4 401 4C-1 Time 3AB 206 309 307-308 Time Time Matsuri: 310 606-609 Band: 6B 616-617 Time 615 620 618-619 Theater: 6A Center: 305 306 613 Time 604 612 Time Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am 7:00am Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed 7:00am FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 29th - 30th (1 of 4) 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am Main Stage Autographs Sakuradome Panels 1 Panels 2 Panels 3 Time 4A 4B 6E Time 6C 4C-2 4C-3 8:00am 8:00am 8:00am Swasey/Mignogna showcase: 8:00am The IDOLM@STER 1-4 Moyashimon 1-4 One Piece 237-248 8:00am 8:00am TO Film Collection: Elliptical 8:30am 8:30am Closed 8:30am 8:30am 8:30am 8:30am (SC-10, sub) (SC-13, sub) (SC-10, dub) 8:30am 8:30am Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed Orbit & Symbiotic Planet (SC-13, dub) 9:00am Located in the Contestants’ 9:00am A/V Tech Rehearsal 9:00am Open 9:00am 9:00am 9:00am AMV Showcase 9:00am 9:00am Green Room, right rear 9:30am 9:30am for Premieres -

Continuing to Innovate with a Focus on Global Business Initiatives Aligned with Changes in Our Markets

NEWSLETTER September 2018 BANDAI NAMCO Holdings Inc. BANDAI NAMCO Mirai-Kenkyusho 5-37-8 Shiba, Minato-ku, Tokyo 108-0014 Mitsuaki Taguchi Interview with the President President & Representative Director, BANDAI NAMCO Holdings Inc. Continuing to innovate with a focus on global business initiatives aligned with changes in our markets Under the Mid-term Plan, the Group announced a mid-term vision of CHANGE for the NEXT — Empower, Gain Momentum, and Accelerate Evolution, and launched a five-Unit system. In the first quarter, the Group achieved record-high sales. In these ways, the Mid-term Plan has gotten off to a favorable start. In this issue of the newsletter, BANDAI NAMCO Holdings’ President Mitsuaki Taguchi discusses the future results forecast and the situation with each of the Group’s Units. How were the results in the first What is the outlook for the future? for the mature fan base, BANDAI SPIRITS quarter? Taguchi: In our industry, the environment is CO., LTD., a new company that consolidates Taguchi: In the first quarter of FY2019.3, in undergoing drastic changes, and it is difficult the mature fan base business of the Toys and comparison with the same period of the previous to forecast all of the future trends based on Hobby Unit, started fullscale operation. With year, each business recorded favorable overall three months of results. Considering bolstered a separate organizational structure and a clarified progress with core IP* and products/services, marketing and promotion for businesses mission, the sense of speed in this business despite differences in the home video game recording favorable results; recent business has increased. -

Friday, July 30, 2010 9:57:00 AM Update

July 30 - August 1, 2010 Baltimore Convention Center Baltimore, Maryland, USA Close This Window Back to main site SHOW ALL DAYS Friday, July 30, 2010 Saturday, July 31, 2010 Sunday, August 1, 2010 Filter by Track/Location: Show ALL Tracks/Locations | Clear All Filters Friday, July 30, 2010 9:57:00 AM 8:00 AM 9:00 AM 10:00 AM 11:00 AM 12:00 PM 1:00 PM 2:00 PM 3:00 PM 4:00 PM 5:00 PM 6:00 PM 7:00 PM 8:00 PM 9:00 PM 10:00 PM 11:00 PM 12:00 AM 1:00 AM 2:00 AM Main Events Concert - Yoshid... Arena Masquerade Registration Video 1 Ah My Buddha La Corda D'Oro P... AMV Overflow Eureka 7: Good Night, Sleep Tigh... AMV Contest Skullman 1-6 Vampire Girl vs. Frankenstein Gi... Urotsukidoji: Legend of the Over... Video 2 Sands of Destruction Gakuen Alice Ikkitousen: Dragon Destiny 1-2 Bamboo Blade 1-4 [S] Utawarerumono 1-... Murder Princess 1-6 [S] Master of Martial Hearts 1-5 [18+] Junjo Romantica Season 1 DVD Col... Cleavage [18+] Video 3 Otaku no Video [S] Yawara! 15-21 [S] Galaxy Express 999 TV 5-8 Masked Rider: The First [S] Dairugger XV 1-6 [S] Cyborg 009: Monster Wars Dragon Ball 53-58 [S] Video 4 Afghan Star [L] Taxi Hunter [L] V3 Samseng Jalanan [L] Paku Kuntilanak... The Kid With the Golden... Power Kids [L] Seven Days [L] Hard Revenge Milly: Bloody Battle Ac... Art of the Devil 3 [L][1.. -

Press Release

Contact: Kristyn Souder Communications Director Email: [email protected] Phone: (267)536-9566 PRESS RELEASE Zenkaikon Convention to Bring Anime and Science Fiction Fans to Lancaster in March Hatboro, PA – January 21, 2013: On March 22-24, 2013, Zenkaikon will hold its seventh annual convention in a new location at the Lancaster County Convention Center in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. The convention expects to welcome over two thousand fans of Japanese animation (anime), comics (manga), gaming, and science fiction to downtown Lancaster for the weekend-long event. Zenkaikon had typically been held in the Valley Forge area of Pennsylvania. However, with the conversion of the Valley Forge Convention Center to a casino and the continued growth of the event, Zenkaikon moved its convention to Lancaster. Many convention attendees don costumes of their favorite characters to attend the annual convention. Planned convention events include a variety of educational panels and workshops hosted by volunteers and guests; anime and live action screenings; a costume and skit competition (the "Masquerade"); a hall costume contest; performances by musical guests; a live action role play ("LARP") event; video game tournaments and tabletop gaming; a formal ball and informal dances; and an exhibit hall of anime-themed merchandise and handmade creations from artists. A number of Guests of Honor have already been announced for Zenkaikon 2013. John de Lancie, best known for his roles on Star Trek and Stargate SG-1, and more recently known for his role as Discord on My Little Pony: Friendship is Magic, will be hosting panels and meeting attendees. Prolific voice and live action actor Richard Epcar (Ghost in the Shell, The Legend of Korra, Kingdom Hearts) and actress Ellyn Stern (Robotech, Gundam Unicorn, Bleach) will also be participating in a variety of programming. -

The Mobile Suit Gundam Franchise

The Mobile Suit Gundam Franchise: a Case Study of Transmedia Storytelling Practices and the Role of Digital Games in Japan Akinori (Aki) Nakamura College of Image Arts and Sciences, Ritsumeikan University 56-1 Toji-in Kitamachi, Kita-ku, Kyoto 603-8577 [email protected] Susana Tosca Department of Arts and Communication, Roskilde University Universitetsvej 1, P.O. Box 260 DK-4000 Roskildess line 1 [email protected] ABSTRACT The present study looks at the Mobile Suit Gundam franchise and the role of digital games from the conceptual frameworks of transmedia storytelling and the Japanese media mix. We offer a historical account of the development of “the Mobile Suit Gundam” series from a producer´s perspective and show how a combination of convergent and divergent strategies contributed to the success of the series, with a special focus on games. Our case can show some insight into underdeveloped aspects of the theory of transmedial storytelling and the Japanese media mix. Keywords Transmedia Storytelling, Media mix, Intellectual Property, Business Strategy INTRODUCTION The idea of transmediality is now more relevant than ever in the context of media production. Strong recognizable IPs take for example more and more space in the movie box office, and even the Producers Guild of America ratified a new title “transmedia producer” in 2010 1. This trend is by no means unique to the movie industry, as we also detect similar patterns in other media like television, documentaries, comics, games, publishing, music, journalism or sports, in diverse national and transnational contexts (Freeman & Gambarato, 2018). However, transmedia strategies do not always manage to successfully engage their intended audiences; as the problematic reception of a number of works can demonstrate. -

Anime Publisher Year a Tree of Palme ADV Films 2005 Abenobashi ADV

Anime Publisher Year A Tree of Palme ADV Films 2005 Abenobashi ADV Films 2005 Ah! My Goddess Pioneer 2000 Air Gear ADV Films 2007 Akira Pioneer 1994 Alien Nine US Manga 2003 Android Kikaider Bandai Entertainment 2002 Angelic Layer ADV Films 2005 Aquarian Age ADV Films 2005 Arjuna Bandai Entertainment 2001 Black Cat Funimation 2005 Black Heaven Pioneer 1999 Black Lagoon Funimation 2006 Blood: The Last Vampire Manga Entertainment 2001 Blood+ Sony Pictures 2005 BoogiePop Phantom NTSC 2001 Brigadoon Tokyo Pop 2003 C Control Funimation 2011 Ceres: Celestial Legend VIS Media 2000 Chevalier D'Eon Funimation 2006 Cowboy Bebop Bandai Entertainment 1998 Cromartie High Scool ADV Films 2006 Dai-Guard ADV Films 1999 Dears Bandai Visual 2004 DeathNote VIS Media 2003 Elfen Lied ADV Films 2006 Escaflowne Bandai Entertainment 1996 Fate Stay/Night TBS Animation 2013 FLCL Funimation 2000 Fruits Basket Funimation 2002 Full Metal Achemist: Brotherhood Funimation 2010 Full Metal Alchemist Funimation 2004 Full Metal Panic? ADV Films 2004 G Gundam Bandai Entertainment 1994 Gankutsuou Gnzo Media Factory 2004 Gantz ADV Films 2004 Geneshaft Bandai Entertainment 2001 Getbackers ADV Films 2005 Ghost in the Shell Bandai Entertainment 2002 Ghost Stories ADV Films 2000 Grave of the Fireflies Central Pak Media 1988 GTO Great Teacher Onizuka Tokyo Pop 2004 Gungrave Pioneer 2004 Gunslinger Girl Funimation 2002 Gurren Lagann Bandai Entertainment 2007 Guyver ADV Films 2007 Heat Guy J Pioneer 2002 Hellsing Pioneer 2002 Infinite Ryvius Bandai Entertainment 1999 Jin-Roh Bandai -

Space Runaway Ideon

Space Runaway Ideon Written by Dan H Space Runaway Ideon, or Legendary Great God Ideon (Densetsu Kyojin Ideon/伝説巨 神イデオン) Director: Yoshiyuki Tomino Production: Sunrise Episodes: 39 Aired: May 1980-Jan 1981 Premise On a sparsely colonized planet in the Andromeda Galaxy, researchers have uncovered the mysterious remains of an ancient ship and three armored vehicles that combine to form a giant robot. They have barely been restored to working order when unusually human-like aliens calling themselves the Buff Clan arrive, believing the planet to be the resting place of a legendary source of infinite energy. When the Buff Clan destroy the human settlement, the survivors escape aboard the ship, using the robot, Ideon, to protect them from the alien pursuers who fear the ancient relics are harbingers of their own destruction. Why It's So Damn Important Mere months after finishing up Mobile Suit Gundam, Tomino Yoshiyuki and Sunrise Studios were back on the air with another new take on the "Super Robot" genre. Like Gundam, Ideon wasn't terribly successful, being canceled before its planned episode run. Unlike Gundam though, Ideon never "took off" afterwards, remaining a "cult" show at best. But if relatively few people actually saw the show, many people in the anime industry saw it and took note, making Ideon paradoxically an influential show nobody remembers. Little "homage shots" to the Ideon and its signature attacks show up all over the place (Gurren-Lagann, for instance), and Anno Hideaki listed Ideon as one of his greatest influences in producing Evangelion. The influence this show had on Evangelion brings up an interesting parallel, since like Anno, Tomino was in the depths of depression while working on Ideon, and this is easily his darkest and most violent work to date. -

Anime Nyc To Host Premiere & Concert For 2Nd Gundam Thunderbolt

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Peter Tatara [email protected] ANIME NYC TO HOST PREMIERE & CONCERT FOR 2ND GUNDAM THUNDERBOLT MOVIE Concert Will Feature Gundam Thunderbolt Composer Naruyoshi Kikuchi NEW YORK, NY (July 18, 2017) - LeftField Media and SUNRISE Inc. today announced the inaugural Anime NYC festival will play host to the US premiere of Mobile Suit Gundam Thunderbolt: Bandit Flower, the second film in the Gundam Thunderbolt series, and that this premiere will be accompanied by a live concert featuring the music of Gundam Thunderbolt led by composer Naruyoshi Kikuchi. Anime NYC powered by Crunchyroll is a new Japanese pop culture convention launching November 17-19, 2017 in New York’s Javits Center, and it will bring fans together with creators and companies from across America and Japan. SUNRISE’s Gundam Thunderbolt premiere and concert will take place within Anime NYC on Sunday, November 19th. Gundam Thunderbolt: Bandit Flower is a sci-fi story grounded in the warfare of today and uniquely brought to life by the music of Naruyoshi Kikuchi. One of Japan’s greatest jazz composers and musicians, Mr. Kikuchi is acclaimed at home in Japan and around the world, and no stranger to anime, he’s also the composer of the Lupin the Third: The Woman Called Fujiko Mine soundtrack and his saxophone can be heard in the music of Cowboy Bebop. Mr. Kikuchi will appear at Anime NYC as an Official Guest, leading and performing in the Gundam Thunderbolt series concert, as well as speaking on panels and signing autographs. “We’re deeply honored to welcome our friends at SUNRISE and Mr. -

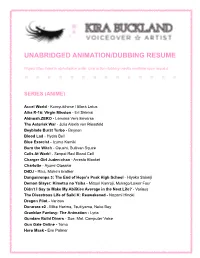

Unabridged Animation/Dubbing Resume

UNABRIDGED ANIMATION/DUBBING RESUME Project titles listed in alphabetical order. Live action dubbing credits available upon request. SERIES (ANIME) Accel World - Kuroyukihime / Black Lotus Aika R-16: Virgin Mission - Eri Shinkai Aldnoah.ZERO - Lemrina Vers Enverse The Asterisk War - Julis Alexia von Riessfeld Beyblade Burst Turbo - Beyeen Blood Lad - Hydra Bell Blue Exorcist - Izumo Kamiki Burn the Witch - Osushi, Sullivan Squire Cells At Work! - Senpai Red Blood Cell Charger Girl Juden-chan - Arresta Blanket Charlotte - Ayumi Otosaka D4DJ - Rika, Maho’s brother Danganronpa 3: The End of Hope’s Peak High School - Hiyoko Saionji Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba - Mitsuri Kanroji, Mukago/Lower Four Didn’t I Say to Make My Abilities Average in the Next Life? - Various The Disastrous Life of Saiki K: Reawakened - Nozomi Hinoki Dragon Pilot - Various Durarara x2 - Mika Harima, Tsukiyama, Neko Boy Granblue Fantasy: The Animation - Lyria Gundam Build Divers - Sue, Mol, Computer Voice Gun Gale Online - Toma Hero Mask - Eve Palmer Heroes: Legend of the Battle Disks - Vulkay Hi Score Girl - Mayumayu (season 2) The Hidden Dungeon Only I Can Enter - Luna High Rise Invasion - Haruka, Young Rika High School Prodigies Have it Easy Even In Another World - Shinobu, Jeanne Hunter x Hunter - Zushi If It’s For My Daughter, I’d Even Defeat a Demon Lord - Maya I’m Standing on 1,000,000 Lives - Hosshi, Majiha Purple Isekai Quartet - Beatrice, Chris JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure: Stardust Crusaders - Jotaro Fangirl (ep 1) JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure: Diamond is Unbreakable -

Mobile Suit Gundam: Seed +1000 CP

Mobile Suit Gundam: Seed It is the Year 70 of the Cosmic Era, which is Gundam Seed's unique calendar. Your decade long stay is defined by escalating tensions between the PLANTs, home to genetically engineered 'coordinators', and the Earth Sphere dominated by so called Naturals, who don't. You arrive shortly after the events of the Bloody Valentine attack on Junius Seven, and ZAFT's deployment of the Neutron Jammers. You have the power to make a difference, don't you? So put it to good use, and have this: +1000 CP For Age roll 2d8+10 and proceed to chose your origin, and if you want to change gender, or age that will be 100cp. Origins: Drop-in: Huh you're whatever you are... and no body knows anything other than what you tell them. On the downside while you don't have any memories, you don't have an memories... or friends. Earth Alliance: You're a citizen of the Earth Alliance so your probably a natural. You can be a citizen of Eurasia, the Atlantic Federation, South Africa or the Republic of East Asia. PLANT: Well your a coordinator and your home is under attack by the Earth Alliance because of your people's genetic modifications. The PLANTs military ZAFT however is equipped with mobile suits. Orb Union: Orb is a neutral state, and economic powerhouse with its own space colonies, and mass driver. Being from Orb means your neutral. Orb is accepting of naturals, and coordinators alike. Locations Roll 1d8 for your start from one of these Locations, or pay 100 to choose: Heliopolis: An Orb space colony. -

Why Fair Use Should Extend to Fan-Based Activities

WHEN HOLDING ON MEANS LETTING GO: WHY FAIR USE SHOULD EXTEND TO FAN-BASED ACTIVITIES Nathaniel T. Noda† INTRODUCTION In a celebrated children’s song, Malvina Reynolds observes that love is “just like a magic penny, / hold it tight and you won’t have any. / Lend it, spend it, and you’ll have so many / They’ll roll all over the floor.” 1 Just as love sometimes means letting go, the doctrine of fair use recognizes that the purposes of copyright are sometimes better served by allowing certain forms of infringing activity to occur. The four-factor test for fair use, codified at 17 U.S.C. § 107, affords courts sufficient latitude to fine tune the analysis in light of changing circumstances. The recent surge of interest in anime and manga, or Japanese animation and comics, 2 brings with it distinctive examples of what may be dubbed “fan-based activities,” which indicate how courts can adapt the fair use analysis to best balance the public’s access to creative works with the interests of copyright holders. The joint popularity of anime and manga is no coincidence: the origin and evolution of manga is entwined with the origin and evolution of anime, representing a symbiosis between the † Mr. Noda is a J.D. Candidate 2009, William S. Richardson School of Law, University of Hawai`i at Manoa. This paper arose within the context of the WSRSL Second-Year Seminar. The author would like to thank Professor Charles D. Booth for his invaluable advice and guidance. 1 Charles H. Smith & Nancy Schimmel, Magic Penny , by Malvina Reynolds, available at http://www.wku.edu/~smithch/MALVINA/mr101.htm. -

SNAFU Con 2012 Schedule! Friday Schedule!

SNAFU Con 2012 Schedule! Welcome to SNAFU Con 2012! You hold in your hands the power to see the future! Or the past. It really depends on your perspective a the time, but that's neither here nor there. Or maybe it's both here and there. Anyway! This is the SNAFU Con 2012 schedule. It is your best chance at making sure you know where to be when cool things are happening. We would love to tell you that cool things are happening everywhere all the time no matter where you are around here, but that, too, is a matter of perspective and taste. We are PACKED with programming this year! You should have no problem keeping busy, no matter what your taste happens to be. We do recommend you find some time to sleep, though. We have all been working hard to make this an absolutely epic year. Enjoy!!! Photo Booth This year we've added a new area for schedule and that is our photography studio. Our photography staff will be all around con taking pictures, but there are set times when our head of photography will be set up and taking free cosplay (or non- cosplay) pictures! We will post the pics on our Facebook page after con! Don't forget to read your con book to find out what all these awesome things are that are going on! Key: Times to BUY Grayed Out The room is closed. Nothing to see here, move along. Vendor Hours Artist Alley Hours Plain Text Something is going on! Friday 1pm – 7pm 12pm – 9pm Bold! Special guests are involved in this panel/event! Saturday 11am – 7pm 9am – 8pm Italics Video programming happening.