April, 2019 Periodic Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nepal Human Rights Year Book 2021 (ENGLISH EDITION) (This Report Covers the Period - January to December 2020)

Nepal Human Rights Year Book 2021 (ENGLISH EDITION) (This Report Covers the Period - January to December 2020) Editor-In-Chief Shree Ram Bajagain Editor Aarya Adhikari Editorial Team Govinda Prasad Tripathee Ramesh Prasad Timalsina Data Analyst Anuj KC Cover/Graphic Designer Gita Mali For Human Rights and Social Justice Informal Sector Service Centre (INSEC) Nagarjun Municipality-10, Syuchatar, Kathmandu POBox : 2726, Kathmandu, Nepal Tel: +977-1-5218770 Fax:+977-1-5218251 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.insec.org.np; www.inseconline.org All materials published in this book may be used with due acknowledgement. First Edition 1000 Copies February 19, 2021 © Informal Sector Service Centre (INSEC) ISBN: 978-9937-9239-5-8 Printed at Dream Graphic Press Kathmandu Contents Acknowledgement Acronyms and Abbreviations Foreword CHAPTERS Chapter 1 Situation of Human Rights in 2020: Overall Assessment Accountability Towards Commitment 1 Review of the Social and Political Issues Raised in the Last 29 Years of Nepal Human Rights Year Book 25 Chapter 2 State and Human Rights Chapter 2.1 Judiciary 37 Chapter 2.2 Executive 47 Chapter 2.3 Legislature 57 Chapter 3 Study Report 3.1 Status of Implementation of the Labor Act at Tea Gardens of Province 1 69 3.2 Witchcraft, an Evil Practice: Continuation of Violence against Women 73 3.3 Natural Disasters in Sindhupalchok and Their Effects on Economic and Social Rights 78 3.4 Problems and Challenges of Sugarcane Farmers 82 3.5 Child Marriage and Violations of Child Rights in Karnali Province 88 36 Socio-economic -

COVID19 Reporting of Naukunda RM, Rasuwa.Pdf

स्थानिय तहको विवरण प्रदेश जिल्ला स्थानिय तहको नाम Bagmati Rasuwa Naukunda Rural Mun सूचना प्रविधि अधिकृत पद नाम सम्पर्क नं. वडा ठेगाना कैफियत सूचना प्रविधि अधिकृतसुमित कुमार संग्रौला 9823290882 ६ गोसाईकुण्ड गाउँपालिका जिम्मेवार पदाधिकारीहरू क्र.स. पद नाम सम्पर्क नं. वडा ठेगाना कैफियत 1 प्रमुख प्रशासकीय अधिकृतनवदीप राई 9807365365 १३ विराटनगर, मोरङ 2 सामजिक विकास/ स्वास्थ्यअण प्रसाद शाखा पौडेल प्रमुख 9818162060 ५ शुभ-कालिका गाउँपालिका, रसुवा 3 सूचना अधिकारी डबल बहादुर वि.के 9804669795 ५ धनगढी उपमहानगरपालिका, कालिका 4 अन्य नितेश कुमार यादव 9816810792 ६ पिपरा गाउँपालिका, महोत्तरी 5 6 n विपद व्यवस्थापनमा सहयोगी संस्थाहरू क्र.स. प्रकार नाम सम्पर्क नं. वडा ठेगाना कैफियत 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 n ारेाइन केको ववरण ID ारेाइन केको नाम वडा ठेगाना केन्द्रको सम्पर्क व्यक्तिसम्पर्क नं. भवनको प्रकार बनाउने निकाय वारेटाइन केको मता Geo Location (Lat, Long) Q1 गौतम बुद्ध मा.वि क्वारेन्टाइन स्थल ३ फाम्चेत नितेश कुमार यादव 9816810792 विध्यालय अन्य (वेड संया) 10 28.006129636870693,85.27118702477858 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q5 Q6 Q7 Q8 Q9 Q10 Q11 Qn भारत लगायत विदेशबाट आएका व्यक्तिहरूको विवरण अधारभूत विवरण ारेाइन/अताल रफर वा घर पठाईएको ववरण विदेशबाट आएको हो भने मात्र कैिफयत ID नाम, थर लिङ्ग उमेर (वर्ष) वडा ठेगाना सम्पर्क नं. -

Raja Ram CHHATKULI, Janak Raj JOSHI, Jagat DEUJA and Uma Shankar PANDAY, Nepal

Participatory Mapping as a Smart Survey Technique to Support Land Rights for All: Experiences and Expectations (Nepal) Raja Ram CHHATKULI, Janak Raj JOSHI, Jagat DEUJA and Uma Shankar PANDAY, Nepal Key words: Land Policy, Land Rights, Security of Tenure, Fit-For-Purpose Land Administration, Participatory Mapping, Social Tenure Domain Model SUMMARY Successive Governments after the political change of 1951 have advocated pro-poor land reforms. After the adoption of new Constitution in 2015, serious attempts have been made in this direction. The National Land Policy (NLUP) adopted in 2019 adheres to the VGGT prinicples and stresses o Living No One Behind (LNOB). NLUP recognizes land rights of women and vulnerable groups, rehabilitation of the landless slum-dwellers, squatters and informal tenure-holders for sustainable and improved housing, access to land and security of tenure for all including the landless peasants. A Fit-For-Purpose Land Administration (FFPLA) approach provides a blueprint for a fast, economic and good enough solution and advocated as such in the Country Level Implementation Strategy for Nepal. To implement the land tenure security provisions of the NLUP, Nepal adopted 8th Amendment to the Lands Act, 1964 which provides for allocation of land to the landless and regularization of informal tenure up-to designated size based on different criteria of the attibutes of the person and the land and the person to land relations. As such the surveying and mapping for the purpose is more than a geomatic measurement activity and entails additional factors of social, economic, cultural and environmental information collection. A Land Issues Resolving Commission (LIRC) has been established and is mandated to undertake this august task. -

Belaka Goat Porject Report

1. Introduction Nepal is an agrarian based country where about 65.6 percent of population is based in agriculture which contributes about 35 percent of GDP. The Nepalese agriculture system comprises of crop, livestock and fodder trees where livestock provides milk, meat, manure, hide draught power, fertilizer, household fuel and fiber. The livestock sector contributes 14% of the national GDP and 32% of the AGDP, which shows significant role of the livestock sector in the country’s economy. The data showed that in total contribution of livestock the contribution of goat meat is 20 percent. Small ruminant especially goat has a significant role in the total livestock contribution. According to MoAC (2004), Goat constitutes a considerable proportion of total ruminants in hills (49.66 % of total ruminants in hills) and Terai (36.47% of total ruminant population) of Nepal, however in case of mountain sheep is more dominated. Thus the sector of goat provides a robust support in the livelihood of Nepalese farmers of hills and terai which constitute the higher proportion of land area and population of the country. According to MOAC (2011), around 75 percent of household are rearing goat which is percent) households. This shows preference of goat over other livestock species for the farm household. They serve as a complement to crop production along with supply of milk and meat. Goat farming is a major part of livestock sector and is mainly adopted by the small as well as marginal farmers whose primary and stable source is income is agriculture. Nepal has long been based on subsistence farming, where the farmers secure their livelihood from fragmented plots of land cultivated in difficult conditions mostly rained where only 28% of the total agricultural land (4.21 million ha) is irrigated 2 (World Bank, 2018). -

S.N Local Government Bodies EN स्थानीय तहको नाम NP District

S.N Local Government Bodies_EN थानीय तहको नाम_NP District LGB_Type Province Website 1 Fungling Municipality फु ङलिङ नगरपालिका Taplejung Municipality 1 phunglingmun.gov.np 2 Aathrai Triveni Rural Municipality आठराई त्रिवेणी गाउँपालिका Taplejung Rural municipality 1 aathraitribenimun.gov.np 3 Sidingwa Rural Municipality लिदिङ्वा गाउँपालिका Taplejung Rural municipality 1 sidingbamun.gov.np 4 Faktanglung Rural Municipality फक्ताङिुङ गाउँपालिका Taplejung Rural municipality 1 phaktanglungmun.gov.np 5 Mikhwakhola Rural Municipality लि啍वाखोिा गाउँपालिका Taplejung Rural municipality 1 mikwakholamun.gov.np 6 Meringden Rural Municipality िेररङिेन गाउँपालिका Taplejung Rural municipality 1 meringdenmun.gov.np 7 Maiwakhola Rural Municipality िैवाखोिा गाउँपालिका Taplejung Rural municipality 1 maiwakholamun.gov.np 8 Yangworak Rural Municipality याङवरक गाउँपालिका Taplejung Rural municipality 1 yangwarakmuntaplejung.gov.np 9 Sirijunga Rural Municipality लिरीजङ्घा गाउँपालिका Taplejung Rural municipality 1 sirijanghamun.gov.np 10 Fidhim Municipality दफदिि नगरपालिका Panchthar Municipality 1 phidimmun.gov.np 11 Falelung Rural Municipality फािेिुुंग गाउँपालिका Panchthar Rural municipality 1 phalelungmun.gov.np 12 Falgunanda Rural Municipality फा쥍गुनन्ि गाउँपालिका Panchthar Rural municipality 1 phalgunandamun.gov.np 13 Hilihang Rural Municipality दिलििाङ गाउँपालिका Panchthar Rural municipality 1 hilihangmun.gov.np 14 Kumyayek Rural Municipality कु म्िायक गाउँपालिका Panchthar Rural municipality 1 kummayakmun.gov.np 15 Miklajung Rural Municipality लि啍िाजुङ गाउँपालिका -

Table of Province 01, Preliminary Results, Nepal Economic Census 2018

Number of Number of Persons Engaged District and Local Unit establishments Total Male Female Taplejung District 4,653 13,225 7,337 5,888 10101PHAKTANLUNG RURAL MUNICIPALITY 539 1,178 672 506 10102MIKWAKHOLA RURAL MUNICIPALITY 269 639 419 220 10103MERINGDEN RURAL MUNICIPALITY 397 1,125 623 502 10104MAIWAKHOLA RURAL MUNICIPALITY 310 990 564 426 10105AATHARAI TRIBENI RURAL MUNICIPALITY 433 1,770 837 933 10106PHUNGLING MUNICIPALITY 1,606 4,832 3,033 1,799 10107PATHIBHARA RURAL MUNICIPALITY 398 1,067 475 592 10108SIRIJANGA RURAL MUNICIPALITY 452 1,064 378 686 10109SIDINGBA RURAL MUNICIPALITY 249 560 336 224 Sankhuwasabha District 6,037 18,913 9,996 8,917 10201BHOTKHOLA RURAL MUNICIPALITY 294 989 541 448 10202MAKALU RURAL MUNICIPALITY 437 1,317 666 651 10203SILICHONG RURAL MUNICIPALITY 401 1,255 567 688 10204CHICHILA RURAL MUNICIPALITY 199 586 292 294 10205SABHAPOKHARI RURAL MUNICIPALITY 220 751 417 334 10206KHANDABARI MUNICIPALITY 1,913 6,024 3,281 2,743 10207PANCHAKHAPAN MUNICIPALITY 590 1,732 970 762 10208CHAINAPUR MUNICIPALITY 1,034 3,204 1,742 1,462 10209MADI MUNICIPALITY 421 1,354 596 758 10210DHARMADEVI MUNICIPALITY 528 1,701 924 777 Solukhumbu District 3,506 10,073 5,175 4,898 10301 KHUMBU PASANGLHAMU RURAL MUNICIPALITY 702 1,906 904 1,002 10302MAHAKULUNG RURAL MUNICIPALITY 369 985 464 521 10303SOTANG RURAL MUNICIPALITY 265 787 421 366 10304DHUDHAKOSHI RURAL MUNICIPALITY 263 802 416 386 10305 THULUNG DHUDHA KOSHI RURAL MUNICIPALITY 456 1,286 652 634 10306NECHA SALYAN RURAL MUNICIPALITY 353 1,054 509 545 10307SOLU DHUDHAKUNDA MUNICIPALITY -

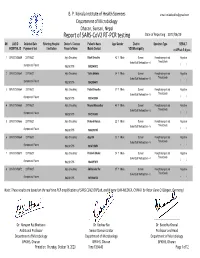

Date Wise PCR REPORT Query

B. P. Koirala Institute of Health Sciences email: [email protected] Department of Microbiology Dharan, Sunsari, Nepal Report of SARS-CoV2 RT-PCR testing Date of Reporting 2077/06/29 SN LAB ID Collected Date Referring Hospital Doctor's / Contact Patient's Name Age/ Gender District Specimen Type RESULT HOSPITAL ID Purpose of test / Institution Person's Name Mobile Contact VDC/Municipality ct ORF1ab; E; N gene 1 BPK/COV/58659 2077/06/27 Aijuk Chaudhary Bibek Shrestha 42Y / Male Sunsari Nasopharyngeal and Negative Throat Swab Itahari Sub Metropolitan - 4 ;; Symptomatic Patient 9862301795 9852048512 2 BPK/COV/58661 2077/06/27 Aijuk Chaudhary Tanka Ghimire 54Y / Male Sunsari Nasopharyngeal and Negative Throat Swab Itahari Sub Metropolitan - 9 ;; Symptomatic Patient 9862301795 9842504411 3 BPK/COV/58664 2077/06/27 Aijuk Chaudhary Parbat Shrestha 27Y / Male Sunsari Nasopharyngeal and Negative Throat Swab Itahari Sub Metropolitan - 5 ;; Symptomatic Patient 9862301795 9803430804 4 BPK/COV/58665 2077/06/27 Aijuk Chaudhary Niramal Manandhar 45Y / Male Sunsari Nasopharyngeal and Negative Throat Swab Itahari Sub Metropolitan - 6 ;; Symptomatic Patient 9862301795 9842183483 5 BPK/COV/58666 2077/06/27 Aijuk Chaudhary Prakash Koirala 22Y / Male Sunsari Nasopharyngeal and Negative Throat Swab Itahari Sub Metropolitan - 5 ;; Symptomatic Patient 9862301795 9868298195 6 BPK/COV/58669 2077/06/27 Aijuk Chaudhary Ajay BK 23Y / Male Sunsari Nasopharyngeal and Negative Throat Swab Itahari Sub Metropolitan - 5 ;; Symptomatic Patient 9862301795 9814715659 7 BPK/COV/58671 2077/06/27 Aijuk Chaudhary Pradosh Dhakal 24Y / Male Sunsari Nasopharyngeal and Negative Throat Swab Itahari Sub Metropolitan - 4 ;; Symptomatic Patient 9862301795 9842057875 8 BPK/COV/58672 2077/06/27 Aijuk Chaudhary Jib Bahadur Rai 37Y / Male Sunsari Nasopharyngeal and Negative Throat Swab Itahari Sub Metropolitan - 6 ;; Symptomatic Patient 9862301795 9815966136 Note: These results are based on the real time PCR amplification of SARS COV2 ORF1ab, and N gene (UNI-MEDICA, CHINA) by Rotor Gene Q (Qiagen, Germany). -

Download/Full-Report-fit-For-Purpose-Land-Administration-A-Country-Level- Implementation-Strategy-For-Nepal/?Wpdmdl=12829&Ind=0 (Accessed on 2 July 2021)

land Article Securing Land Rights for All through Fit-for-Purpose Land Administration Approach: The Case of Nepal Uma Shankar Panday 1,* , Raja Ram Chhatkuli 2, Janak Raj Joshi 3, Jagat Deuja 4,5, Danilo Antonio 6 and Stig Enemark 7 1 Department of Geomatics Engineering, Kathmandu University, Dhulikhel 45200, Nepal 2 UN-Habitat, P.O. Box 107, Kathmandu 44600, Nepal; [email protected] 3 Ministry of Land Management, Cooperatives and Poverty Alleviation, Kathmandu 44600, Nepal; [email protected] 4 Community Self Reliance Centre (CSRC), Kathmandu 44700, Nepal; [email protected] 5 Land Issues Resolving Commission (LIRC), Kathmandu 44620, Nepal 6 UN-Habitat/LHSS, P.O. Box 30030, Nairobi 00100, Kenya; [email protected] 7 Department of Planning, The Technical Faculty of IT and Design, Aalborg University, 9000 Aalborg, Denmark; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +977-11-415100 Abstract: After the political change in Nepal of 1951, leapfrog land policy improvements have been recorded, however, the land reform initiatives have been short of full success. Despite a land ad- ministration system based on cadaster and land registries in place, 25% of the arable land with an estimated 10 million spatial units on the ground are informally occupied and are off-register. Recently, a strong political will has emerged to ensure land rights for all. Providing tenure security to all these occupants using the conventional surveying and land administration approach demands a large amount of skilled human resources, a long timeframe and a huge budget. To assess the suitability of the fit-for-purpose land administration (FFPLA) approach for nationwide mapping and registration Citation: Panday, U.S.; Chhatkuli, of informality in the Nepalese context, the identification, verification and recordation (IVR) of the R.R.; Joshi, J.R.; Deuja, J.; Antonio, D.; people-to-land relationship was conducted through two pilot studies using a participatory approach Enemark, S. -

Q&A from Bidders Conference

Q&A from Bidders Conference (Nov 27) 1. Is the submission deadline still 11 December, 2020? Yes, the deadline for submission of proposal is 11 December, 2020. 2. What is the budget for each Contract? Contract 1: USD 1,621,400 Contract 2: USD 2,661,347 Contact 3: USD 586,020 3. Can a Pvt. Ltd. company be mentioned as suppliers? No, Pvt. Ltd. companies are not eligible to apply for the project. 4. Can we select which locations to work in? No, you must work in the identified Provinces, districts and municipalities. See question 5. 5. In which specific Provinces, districts, metropolitan cities, and municipalities will the project be implemented? The project will be implemented in Province 1 and Sudur Paschim Province. Districts, Metropolitan Cities, and Municipalities: Morang (Biratnagar), Okhaldhunga (Siddhicharan Municipality, Manebhanjyang Rural Municipality, Molung Rural Municipality, Chisankhugadi Rural Municipality), Udayapur (Katari Municipality, Triyuga Municipality, Chaudandigadhi Municipality, Belaka Municipality), Kailali (Dhangadhi), Accham (Mangalsen Municipality, Kamalbazaar Municipality, Sanphebagar Municipality), Baitadi (Patan Municipality, Dasrathchand Municipality), Bajhang (Jaya Prithwi Municipality, Bitthadchir Municipality), and Bajura (Badhimalika Municipality, Budhiganga Municipality). 6. What are the standard payment terms of the contract? Will this be in payment arrears based on completion of deliverables? Standard practice is payment in advance on a quarterly basis, after the implementing partner send quarterly workplans and budgets to UNFPA. 7. Can Universities or Research Institutions also be a part of the project? Only non-governmental and not-for-profit organisations can apply to be an implementing partner and/or sub-contractee. 8. Does an applying organization have to implement the project in both provinces (Province 1 and Sudur Paschim Province), or is there the possibility to choose only one province? Applying organisations cannot choose and must implement the project in both provinces. -

Gender-Based Violence Prevention and Response Project Ii

GENDER-BASED VIOLENCE PREVENTION AND RESPONSE PROJECT II Embarking on a New Chapter in Nepal’s Commitment to Ending Gender-based Violence A CRUCIAL MOMENT IN TIME Gender-based violence (GBV) is an epidemic that thrives all the more during emergencies. The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in a significant spike in domestic violence, as women during lockdown are confined for extended periods of time with their abusers and are unable to access support services. Although several policies, legislation and programmes for GBV prevention and the provision of response services have been put in place in Nepal, and there are encouraging signs of progress, much more needs to be done to end this scourge. This includes challenging social norms that value men and boys over women and girls and perpetuate discriminatory practices and violence against women and girls. (NDHS 2016) GBV IN NEPAL AT A GLANCE 31% male respondents believe that it is acceptable to beat their 31% wives for disobedience one in four married women 66% of GBV survivors have not experienced spousal sought any help or talked with one in five women aged 15-49 physical, sexual or emotional 66% anyone about resisting or stopping experienced physical violence violence in her lifetime the violence they experience BUILDING ON THE ACHIEVEMENTS ABOUT THE PHASE II PROJECT In 2016, the United Nations Population Fund The second phase of the Gender Based Violence (UNFPA) in collaboration with the Government of Prevention and Response (GBVPR) Project Nepal, and supported by the Norwegian Embassy (2020- 2024) will continue efforts to sustain the and the Swiss Agency for Development and emerging results and expand a comprehensive Cooperation, launched the first phase of projects model of prevention and response through an ‘all of in Province 1, Province 3 and Sudurpaschim that community approach’ that allows more sustainable aimed to reduce GBV by empowering women shifts in attitudes and behaviours of individuals and girls and strengthening response services. -

Project Location (District, VDC)

Duration of Supported Name of the project Project location Total Budget by SN Project Sector the project (Month & (district, VDC) (Rs.) (Funding Year) org.) Entrepreneurs/Enter 1 MEDPA 6 Months Udayapur ( 4 Palikis) 63,81381.00 CSIO/UNDP prise RET Orientation AEPC/GI workshop Udayapur , Solukhumbu, 2 2 Months 6,17,000 GIZ Z organization to LGs Okhaldhunga and Khotang in Province 1 Udayapur gadhi Udayapurgadhi Ga.Pa.-6, udayapurgadhi, 3 Skill Development 1 Month 160000 Ga.Pa, Nepaltar ga.pa Udayapur CSIO, CSIO, 4 Skill Development 7 days Tri.Na.pa-10, Bokse 70,000 Udayapur Udayapur Rauta Mai Rural Municipality, CSIDB/ Entrepreneurs/Enter CSIDB, 5 6 month Triyuga, Chaudandigadhi and 4507656/- MEDPA prise Udayapur Belaka Municipality Enterprise CSIO , Development 6 Lahan 2 month Karjanha Municipality, Siraha 218000/- CSIO, Siraha Strategic Plan, SIraha Karjanha CSIO, Third Party 7 Lahan 1 month Siraha District 109000/- CSIO, Siraha Evaluation Siraha Enterprise CSIO, Development 8 2 month Rupani Rural Municipality ,Saptari 218000/- CSIO, Saptari Saptari Strategic Plan , Rupani Enterprise DCSI, 2075.2.1 to 9 Development Surunga Na.Pa. Saptari 200000 DCSI, Saptrai Spatari 2075.2.31 Strategic Plan 11sep 2017 Med Model 10 MEDEP to 31 dec Khotang 249786.50 Medep/Undp Orientation 2017 From : DCC , Evaluation of Financial & 2074.01.25 11 Tapli Gaupalika ( Legau, Iname) 1,50,000.00 DCC Udayapur Social aspects of road To : 074.03.30 Udayapur District - Katari Municipality Chaudandigadi Municipality, Belaka Municipality, Rauta Rural th municipality , Sunkoshi Rural From: 12 municipality , Udayapurgadi MCG/ES June 2017 12 Awareness on election Rural municipality Rs. 16,23,132 ESP/UNDP P/UNDP To: 31 July 2017 Khotang District - Rupakot Municipality, Halesi Municipality, Diprung Rural Municipality, Lamidanda Rural Municipality, Jantedunga Rural UdayapurMunicipality, District Kepilashgadhi - RuralKatari Municipality) Municipality From:16th Chaudandigadi MCG/ESP/U Women awareness April 2017 13 Municipality,Belaka Rs. -

Basin Management Center, Koshi

Government of Nepal Ministry of Forests and Environment Department of Forests and Soil Conservation Basin Management Center, Koshi Gaighat, Udayapur, Nepal 2078 Report on Landslide Inventory of Federal Constituency 2, Udayapur District, Nepal FOREWORDS Landslide is one of the main natural disasters in Nepal, responsible for huge social and economic losses for mountain populations. The annual loss of lives and property due to landslides is significantly high in Nepal. Landslide Inventory is an important tool for disaster management, basic data collection and their management. The landslide Inventory provide required knowledge of landslide occurence pattern, condition of certain region, which is useful for the community in planning, mitigating, and avoiding the danger. Landslides are the results of various causative factors affecting slope instability at a specific location. The first step generally is to map individual landslides and subsequently digitize them for the purpose of a landslide inventory. In this regard, preparation of the landslide inventory database is utmost desirable component. Further the preparation of landslide hazard mapping with the help of identified landslides is very much helpful to prepare management plan of the affected area. The Landslide hazard analysis and mapping cope to provide useful information for catastrophic loss reduction, and assist in the development of guidelines for sustainable land-use planning. In this context, the Basin Management center, Koshi under the Department of Forests and Soil Conservation (DoFSC), Babarmahal, Kathmandu has planned to carry out the preparation of landslide inventory at distric level. Since there is an inadequate documentation on landslides, this Landslide Inventory and Mapping is hoped to be a milestone for further documentation in larger scale in the Basin level.