Surveying Activities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

James Duncan Graham

PEOPLE MENTIONED IN CAPE COD: JAMES DUNCAN GRAHAM “NARRATIVE HISTORY” AMOUNTS TO FABULATION, THE REAL STUFF BEING MERE CHRONOLOGY “Stack of the Artist of Kouroo” Project James Duncan Graham HDT WHAT? INDEX THE PEOPLE OF CAPE COD:JAMES DUNCAN GRAHAM CAPE COD: This light-house, known to mariners as the Cape Cod or PEOPLE OF Highland Light, is one of our “primary sea-coast lights,” and is CAPE COD usually the first seen by those approaching the entrance of Massachusetts Bay from Europe. It is forty-three miles from Cape Ann Light, and forty-one from Boston Light. It stands about twenty rods from the edge of the bank, which is here formed of clay. I borrowed the plane and square, level and dividers, of a carpenter who was shingling a barn near by, and using one of those shingles made of a mast, contrived a rude sort of quadrant, with pins for sights and pivots, and got the angle of elevation of the Bank opposite the light-house, and with a couple of cod-lines the length of its slope, and so measured its height on the shingle. It rises one hundred and ten feet above its immediate base, or about one hundred and twenty-three feet above mean low water. Graham, who has carefully surveyed the extremity of the Cape, GRAHAM makes it one hundred and thirty feet. The mixed sand and clay lay at an angle of forty degrees with the horizon, where I measured it, but the clay is generally much steeper. No cow nor hen ever gets down it. -

![THE BUTLER Faiyfily L]V Aftie'.R.ICA](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9004/the-butler-faiyfily-l-v-aftie-r-ica-2019004.webp)

THE BUTLER Faiyfily L]V Aftie'.R.ICA

THE BUTLER FAiyfILY l]V AftiE'.R.ICA COMPILED BY WILLIAM DAVID BUTLER of St. Louis, Mo. JOHN CROMWELL BUTLER late of Denver, Col, JOSEPH MAR.ION BUTLER of Chicago, Ill. Published by SHALLCROSS PRINTING CO. St. Louis, Mo. THIS Boox IB DEDICATED TO THE BUTLER FAMILY IN AMERICA INTRODUCTION TO BUTLER HISTORY. In the history of these l!niteJ States, there are a few fami lies that have shone witb rare brilliancy from Colonial times, through the Revolution, the \Var of 1812, the ::-.rexican \Var and the great Civil conflict, down to the present time. Those of supe rior eminence may ~asily be numbered on the fingers and those of real supremacy in historical America are not more than a 1,andftil. They stand side by side, none e1wious of the others but all proud to do and dare, and, if need be, die for the nation. Richest and best types of citizens have they been from the pioneer days of ol!r earliest forefathers, and their descendants have never had occasion to apologize for any of them or to conceal any fact connected with their careers. Resplenclant in the beg-inning, their nobility of bloocl has been carrieJ uow11\\·arci pure and unstainecl. °'.\l)t :.ill ui Lheir Jcscenuants ha\·e been distinguished as the world ~·ues-the ,·:i~t majority of them ha\·e been content \\·ith rno<lest lines-bnt :dl ha\c been goocl citizens and faithful Americans. Ami what more hc>l!Or than that can be a,P.rclecl to them? . Coor<lim.te with the _·\clamses, of ::-.r:i.ss::iclrnseth. -

ABRAHAM LINCOLN’S WHITE DREAM (Johnson Publishing, 1999)

GO TO MASTER INDEX OF WARFARE 1 TWO PRESIDENTS, EMBODIMENTS OF AMERICAN RACISM “Lincoln must be seen as the embodiment, not the transcendence, of the American tradition of racism.” — Lerone Bennett, Jr., FORCED INTO GLORY: ABRAHAM LINCOLN’S WHITE DREAM (Johnson Publishing, 1999) 1. “Crosseyed people look funny.” — This is the 1st known image of Lincoln, a plate that was exposed in about 1846. Lincoln had a “lazy eye,” and at that early point the Daguerreotypists had not yet learned how to pose their subjects in order to evade the problem of one eye staring off at an angle. This wasn’t just Susan B. Anthony, and Francis Ellingwood Abbot, and Abraham Lincoln, and Jean-Paul Sartre, and Galileo Galilei, and Ben Turpin and Marty Feldman. Actually, this is a very general problem, with approximately one person out of every 25 to 50 suffering from some degree of strabismus (termed crossed eyes, lazy eye, turned eye, squint, double vision, floating, wandering, wayward, drifting, truant eyes, wall eyes described as having “one eye in York and the other in Cork”). Strabismus that is congenital, or develops in infancy, can create a brain condition known as amblyopia, in which to some degree the input from an eye are ignored although it is still capable of sight — or at least privileges inputs from the other eye. An article entitled “Was Rembrandt stereoblind?,” outlining research by Professor Margaret Livingstone of Harvard University and colleagues, was published in the September 14, 2004, issue of the _New England Journal of Medicine_. Rembrandt, a prolific painter of self-portraits, producing almost 100 if we include some 20 etchings. -

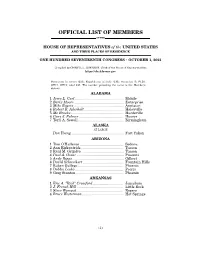

Official List of Members by State

OFFICIAL LIST OF MEMBERS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES of the UNITED STATES AND THEIR PLACES OF RESIDENCE ONE HUNDRED SEVENTEENTH CONGRESS • OCTOBER 1, 2021 Compiled by CHERYL L. JOHNSON, Clerk of the House of Representatives https://clerk.house.gov Democrats in roman (220); Republicans in italic (212); vacancies (3) FL20, OH11, OH15; total 435. The number preceding the name is the Member's district. ALABAMA 1 Jerry L. Carl ................................................ Mobile 2 Barry Moore ................................................. Enterprise 3 Mike Rogers ................................................. Anniston 4 Robert B. Aderholt ....................................... Haleyville 5 Mo Brooks .................................................... Huntsville 6 Gary J. Palmer ............................................ Hoover 7 Terri A. Sewell ............................................. Birmingham ALASKA AT LARGE Don Young .................................................... Fort Yukon ARIZONA 1 Tom O'Halleran ........................................... Sedona 2 Ann Kirkpatrick .......................................... Tucson 3 Raúl M. Grijalva .......................................... Tucson 4 Paul A. Gosar ............................................... Prescott 5 Andy Biggs ................................................... Gilbert 6 David Schweikert ........................................ Fountain Hills 7 Ruben Gallego ............................................. Phoenix 8 Debbie Lesko ............................................... -

Kentucky Humanities Council Catalog 2008-2009 Kentucky Library Research Collections Western Kentucky University, [email protected]

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Kentucky Humanities Council Catalog Kentucky Library - Serials 2008 Kentucky Humanities Council Catalog 2008-2009 Kentucky Library Research Collections Western Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/ky_hum_council_cat Part of the Public History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Kentucky Library Research Collections, "Kentucky Humanities Council Catalog 2008-2009" (2008). Kentucky Humanities Council Catalog. Paper 26. https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/ky_hum_council_cat/26 This Magazine is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kentucky Humanities Council Catalog by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. KENTUCKY HUMANITIES COUNCIL, INC. 2008-2009 NTIES Catalog h A new Chautauqua drama! Mary Owens, Lincoln's First Mary Read all about her on page 25. * whole Humanities Catalog August 1,2008-July 31,2009 "he Whole Humanities Catalog of 2008-09 is all about choices—dozens and dozens of programs on a vast variety of topics. And they are excellent, pow ered by the passion of our speakers and Chautauquans for the stories they have to tell. Mix these great stories with the eager audiences our sponsors provide in almost every Kentucky county, and the result is the magic of the humanities— education, insight, and enjoyment for all. We hope you'll savor these unique pro grams, available only in this catalog. It is your continuing and much-appreciated support that makes them possible. Contents credits 1 Speakers Bureau 2 Featured Speakers and Writers 3 More Speakers 16 Speakers Bureau Travel Map 17 Kentucky Chautauqua including school programs 18 Application Instructions 28 Application Forms Inside Back Cover Telling Kentucky's Story www.kyhumanities.org You'll find this catalog and much more on our website. -

Collection 1805.060.021: Photographs of Union and Confederate Officers in the Civil War in America – Collection of Brevet Lieutenant Colonel George Meade U.S.A

Collection 1805.060.021: Photographs of Union and Confederate Officers in the Civil War in America – Collection of Brevet Lieutenant Colonel George Meade U.S.A. Alphabetical Index The Heritage Center of The Union League of Philadelphia 140 South Broad Street Philadelphia, PA 19102 www.ulheritagecenter.org [email protected] (215) 587-6455 Collection 1805.060.021 Photographs of Union and Confederate Officers - Collection of Bvt. Lt. Col. George Meade U.S.A. Alphabetical Index Middle Last Name First Name Name Object ID Description Notes Portrait of Major Henry L. Abbott of the 20th Abbott was killed on May 6, 1864, at the Battle Abbott Henry L. 1805.060.021.22AP Massachusetts Infantry. of the Wilderness in Virginia. Portrait of Colonel Ira C. Abbott of the 1st Abbott Ira C. 1805.060.021.24AD Michigan Volunteers. Portrait of Colonel of the 7th United States Infantry and Brigadier General of Volunteers, Abercrombie John J. 1805.060.021.16BN John J. Abercrombie. Portrait of Brigadier General Geo. (George) Stoneman Chief of Cavalry, Army of the Potomac, and staff, including Assistant Surgeon J. Sol. Smith and Lieutenant and Assistant J. Adjutant General A.J. (Andrew Jonathan) Alexander A. (Andrew) (Jonathan) 1805.060.021.11AG Alexander. Portrait of Brigadier General Geo. (George) Stoneman Chief of Cavalry, Army of the Potomac, and staff, including Assistant Surgeon J. Sol. Smith and Lieutenant and Assistant J. Adjutant General A.J. (Andrew Jonathan) Alexander A. (Andrew) (Jonathan) 1805.060.021.11AG Alexander. Portrait of Captain of the 3rd United States Cavalry, Lieutenant Colonel, Assistant Adjutant General of the Volunteers, and Brevet Brigadier Alexander Andrew J. -

Butler Family Papers 1778-1975; Predominant 1830-1900 2134 Items

MSS 102 Butler Family Papers 1778-1975; predominant 1830-1900 2134 Items These family papers center around the family of Edward George Washington Butler (1800- 1888), the son of Col. Edward Butler, one of the “Five Fighting Butlers” of Revolutionary War fame. Edward G. W. Butler was married to Frances Parke Lewis of Woodlawn Plantation, Virginia. She was the daughter of Eleanor Parke Custis and Lawrence Lewis of Woodlawn Plantation. E. G. W. Butler was made the ward of General Andrew Jackson after the death of his father. After graduation from the U. S. Military Academy at West Point, Butler served in the U. S. Army as 2nd Lieutenant, 4th Artillery (1821), as Second on Topographical Duty (1820-1923), as Aide de Camp to Bvt. Major General Edmund Pendleton Gaines, and as Acting Asst. Adjutant General, Eastern and Western Departments, 1823-1831. Butler resigned from the Army on May 28, 1831. During the years 1846-1847, Butler served as Maj. General in the Louisiana State Militia. In 1847 he was reappointed to the U. S. Army, with the rank of Colonel, Third Dragoons. He served in the Mexican War, in command of the District of the Upper Rio Grande, from September, 1847 - June 1848. After his marriage, Butler lived in Louisiana, where he owned and worked several plantations in the Iberville Parish area. His primary residence was Dunboyne Plantation, Iberville Parish, La. He died in St. Louis, Missouri, in 1888. The Butler Family Papers consist of correspondence (1778-1972) between family members, including letters from John Parke Custis to George Washington, and from Andrew Jackson to various family members. -

Niagara Falls) to the West

THE SUBLIME FALLS –– HENRY DIDN’T GO THERE February 12, Wednesday: ... There is something more than association at the bottom of the excitement which the roar of a cataract produces. It is allied to the circulation in our veins We have a waterfall which corresponds even to Niagara somewhere within us. It is astonishing what a rush & tumult a slight inclination will produce in a swolen brook. How it proclaims its glee –its boisterousness –rushing headlong in its prodigal course as if it would exhaust itself in half an hour – how it spends itself– I would say to the orator and poet Flow freely & lavishly as a brook that is full –without stint –perchance I have stumbled upon the origin of the word lavish. It does not hesitate to tumble down the steepest precipice & roar or tinkle as it goes, –for fear it will exhaust its fountain.– The impetuosity of descending waters even by the slightest inclination! It seems to flow with ever increasing rapidity. It is difficult to believe what Philosophers assert that it is merely a difference in the form of the elementary particles, as whether they are square or globular –which makes the difference between the steadfast everlasting & reposing hill-side & the impetuous torrent which tumbles down it.... THE SCARLET LETTER: There was one thing that much aided me in renewing and re-creating the stalwart soldier of the Niagara frontier – the man of true and simple energy. It was the recollection of those memorable words of his –“I’ll try, Sir”– spoken on the very verge of a desperate and heroic enterprise, and breathing the soul and spirit of New England hardihood, comprehending all perils, and encountering all. -

Bird-Johnston Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8nz8d2z No online items Bird-Johnston Collection Finding aid prepared by Brooke M. Black Manuscripts Department The Huntington Library 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Fax: (626) 449-5720 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org © 2015 The Huntington Library. All rights reserved. Bird-Johnston Collection mssHM 64970-65036 1 Descriptive Summary Title: Bird-Johnston collection Dates: 1845-1848 Collection Number: mssHM 64970-65036 Collector: Bird, Nancy J., donor Extent: 67 pieces in 2 boxes Repository: The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens Manuscripts Department The Huntington Library 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2203 Fax: (626) 449-5720 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org Abstract: This collection, which deals with the Mexican War, consists of correspondence, military orders, reports, lists of prisoners, and paroles of honor, dating from 1845-1848. The material deals with: troop movements, food and supplies, recruiting and enlistments, mustering of volunteers, as well as Jalapa, Puebla, Tampico, and Veracruz, Mexico. Language of Material: The records are in English and Spanish. Access Open to qualified researchers by prior application through the Reader Services Department. For more information, contact Reader Services. Publication Rights The Huntington Library does not require that researchers request permission to quote from or publish images of this material, nor does it charge fees for such activities. The responsibility for identifying the copyright holder, if there is one, and obtaining necessary permissions rests with the researcher. Preferred Citation [Identification of item]. Bird-Johnston Collection, The Huntington Library, San Marino, California. -

La Contraguerrilla Poblana O Mexican Spy Company (Junio 1847-Junio 1848) ¿Una Forma De Protesta Social?

UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL AUTÓNOMA DE MÉXICO FACULTAD DE FILOSOFÍA Y LETRAS LA CONTRAGUERRILLA POBLANA O MEXICAN SPY COMPANY (JUNIO 1847-JUNIO 1848) ¿UNA FORMA DE PROTESTA SOCIAL? TESIS QUE PARA OBTENER EL TÍTULO DE: LICENCIADO EN HISTORIA PRESENTA: SALVADOR VÁZQUEZ VILLAGRÁN DIRECTOR DE TESIS: DR. MIGUEL SOTO ESTRADA CIUDAD UNIVERSITARIA 2016. UNAM – Dirección General de Bibliotecas Tesis Digitales Restricciones de uso DERECHOS RESERVADOS © PROHIBIDA SU REPRODUCCIÓN TOTAL O PARCIAL Todo el material contenido en esta tesis esta protegido por la Ley Federal del Derecho de Autor (LFDA) de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos (México). El uso de imágenes, fragmentos de videos, y demás material que sea objeto de protección de los derechos de autor, será exclusivamente para fines educativos e informativos y deberá citar la fuente donde la obtuvo mencionando el autor o autores. Cualquier uso distinto como el lucro, reproducción, edición o modificación, será perseguido y sancionado por el respectivo titular de los Derechos de Autor. Para mis padres Manuel y Antonia con mucho cariño y agradecimiento. Siempre están en mi mente. Para María Isabel por su amor y apoyo incondicional. Para Gabriel, Manuel y Gustavo. Gracias por existir y formar parte de mi vida. 2 AGRADECIMIENTOS A la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México por haberme dado la oportunidad de estudiar la licenciatura en Historia. Al Dr. Miguel Soto por sus acertados consejos, tiempo y paciencia mientras duró la investigación. También le dedico a él la tesis. A los maestros Ana Rosa Suárez, Silvestre Villegas, Marcela Terrazas y Emmanuel Rodríguez por sus observaciones y comentarios que fueron enriqueciendo el texto. Al Dr. -

Life of John Davis

\ %,.^^ :Mk- %/ .'M'v %/ •• .-^^^-^ ,1' **'% °^w^- -J .0^ 0^ 0* .^^ ^0 ^ n\ LIFE OF John Davis, BY W. W. H. DAVIS, A.M. 5or )Pri&atc CircuEation. DOYLESTOWN, PA. 1 886. Press of " Department, • Democrat Job Doylestown, Pa. A Labor of Love. —Sr. Paul. Illustrations. - 1. John Davis, - - Frontispiece. 2. Oath of Ali.egiancf,, - - - 50. - - - 100. j{. Amv Hart, - 4. Old Saw Mill, - - 125. - - 5. W. W. H. Davis, 150. 6. Family Rksidence, - - - 190- John Davis. CHAPTER I. John Davis was descended of Welsh and North of Ireland ancestors. William Davis, his grandfather, came from Great Britain about 1740, and settled in Solebury town- ship, Bucks county, Pa., near the line of Upper Make- field. It was generally supposed, in the absence of testimony, he was born in Wales and came direct from that country, but it is now believed he was a native of London, whence he immigrated to America. The name, however, bespeaks his descent without regard to birthplace. Some of the family claim his descent to be Scotch-Welsh. Nothing is positively known of the family before William Davis came to America. It comes down, by tradition, that the American ancestor had two brothers. One of them went to the West Indies, engaged in planting, made a fortune and returned to England to enjoy it ; the other remained in London, studied and practiced law, became distinguished in his profession, and received the honors of knight- hood. An effort was made, many years ago, to re- — 4 JOHN DAVIS. cover an estate in England, said to have been left by one of these brothers, who died without issue, but the papers were lost and the matter given up. -

Annotations for Alexander Von Humboldt's Political Essay on The

Annotations for Alexander von Humboldt’s Political Essay on the Kingdom of New Spain by Giorleny D. Altamirano Rayos, Tobias Kraft, and Vera M. Kutzinski Unless context made it more sensible to do otherwise, we have annotated a reference or allusion at its first occurrence. Entries in boldface refer back to a main entry. The page numbers that precede each entry refer to the pagination of Alexander von Humboldt’s 1826 French edition; those page numbers are are printed in the margins of our translation of the Political Essay on the Kingdom of New Spain. In that edition, the names and concepts that appear in SMALL CAPS in the annotations are marked with an ▼. Weights and Measures What follows are some of the most common weights and measures that Alexander von Humboldt regularly uses. This is not an exhaustive list. ACRE: an old English unit of surface area equivalent to 4,840 square yards (or about 4,046.85 square meters) in the USA and Canada. The standard unit of measurement for surface area in the UK, an acre in its earliest English uses was probably the amount of land that one yoke of oxen could plow in a day. Its value varied slightly in Ireland, Scotland, and England. In France, the size of the acre varied depending on region. Humboldt states that an acre is 4,029 square meters. 2 ARPENT: a unit either of length or of land area used in France, Québec, and Louisiana from the sixteenth to the eighteenth century. The main measurement for land throughout France (sometimes called the French acre), the arpent varied in value depending on region.