The Role of University Museums in the Formation of New Cultural Layers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RE-THINKING METHODOLOGY IPCC2018 Interdisciplinary Phd

YÖNTEMİ YENİDEN DÜŞÜNMEK IPCC2018 Disiplinlerarası Doktora Öğrencileri İletişim Konferansı İstanbul Bilgi Üniversitesi, İletişim Bilimleri Doktora Programı 28-29 Mayıs santralistanbul Kampüsü RE-THINKING METHODOLOGY IPCC2018 Interdisciplinary PhD Communication Conference İstanbul Bilgi University, PhD in Communication Program May 28-29 santralistanbul Campus Scientific Committee Aslı Tunç Asu Aksoy Barış Ursavaş Emine Eser Gegez Erkan Saka Esra Ercan Bilgiç Feride Çiçekoğlu Feyda Sayan Cengiz Gonca Günay Gökçe Dervişoğlu Halil Nalçaoğlu Itır Erhart Nazan Haydari Pakkan Serhan Ada Yonca Aslanbay Organization Committee Adil Serhan Şahin Can Koçak Dilek Gürsoy Melike Özmen Onur Sesigür Book and Cover Design: Melike Özmen Web Design: Dilek Gürsoy Proofreading: Can Koçak http://ipcc.bilgi.edu.tr [email protected] ipcc2018 ipcc2018 with their contribution: Reflections on IPCC2018 Re-Thinking Methodology Nazan Haydari “This is a call from a group of doctoral students for the doctoral students sharing similar concerns about the lack of feedback and interaction in large conferences and in quest for opportunities of building strong and continuous academic connections. We would like to invite you collaboratively discuss and redefine our researches, and methodologies. We believe in the value of constructive feedback in the various stages of our researches”. (CFP of IPCC 2018) Conferences are significant spaces of knowledge production bringing variety of concerns and approaches together. This intellectual attempt carries the greatest value, as Margaret Mead* pointed out only when the shift from one-to-many/single channel communication to many-to-many/multimodal communication is taken for granted. Nowadays, in parallel to increasing number of national and international conferences, a perception about the size of the conference being in close relationship with the quality of the conferences has developed. -

GAZİANTEP ZEUGMA MOZAİK MÜZESİ We Have a New Museum: Gaziantep Zeugma Mozaic Museum

EKİM-KASIM-ARALIK 2011 OCTOBER-NOVEMBER-DECEMBER 2011 SAYI 3 ISSUE 3 Yeni bir müzemiz oldu: GAZİANTEP ZEUGMA MOZAİK MÜZESİ We have a new museum: Gaziantep Zeugma Mozaic Museum KÜLTÜRE ve SANATA CAN SUYU: DÖSİMM Life line support for history, culture and art: DÖSİMM TOKAT ATATÜRK EVİ ve Etnografya Müzesi The Atatürk House and Etnographic Museum in Tokat Başarısını talanıyla gölgeleyen SCHLIEMANN Schliemann who overshadowed his success with his pillage MEDUSA: Mitolojinin yılan saçlı kahramanı Medusa: Mythological heroine with snakes for hair İSTANBUL ARKEOLOJİ MÜZELERİ KOLEKSİYONUNDAN IYI ÇOBAN ISA İyi Çoban İsa ensesine oturttuğu koçun ayaklarını sağ eli ile tutmuştur. Kısa bir tunik giymiş olup giysisini belinden bir kuşakla bağlamıştır. Başını yukarı doğru kaldırmıştır. Kısa dalgalı saçları yüzünü çevirmektedir. Sırtındaki koçun anatomik yapısı çok iyi işlenmiştir. Ana Sponsor İstanbul Arkeoloji Müzeleri TÜRSAB’ın desteğiyle yenileniyor İstanbul Arkeoloji Müzeleri Osman Hamdi Bey Yokuşu Sultanahmet İstanbul • Tel: 212 527 27 00 - 520 77 40 • www.istanbularkeoloji.gov.tr EKİM-KASIM-ARALIK 2011 OCTOBER-NOVEMBER-DECEMBER 2011 SAYI 3 ISSUE 3 Yeni bir müzemiz oldu: GAZİANTEP ZEUGMA içindekiler MOZAİK MÜZESİ We have a new museum: Gaziantep Zeugma Mozaic Museum KÜLTÜRE ve SANATA CAN SUYU: DÖSİMM Life line support for history, culture and art: DÖSİMM TOKAT ATATÜRK EVİ ve Etnografya Müzesi The Atatürk House and Etnographic Museum in Tokat Başarısını talanıyla gölgeleyen SCHLIEMANN Schliemann who overshadowed his success with his pillage MEDUSA: Mitolojinin yılan saçlı kahramanı Medusa: Mythological heroine with snakes for hair 5 Başyazı Her taşı bir tarih sahnesi 22 Dünya tarihinin ev sahibi BRITISH MUSEUM 8 36 KÜLTÜRE ve SANATA can suyu 46 Taşa çeviren bakışlar Tarihin AYAK İZLERİ.. -

SEZİN ÖNER Address

SEZİN ÖNER Address: Kadir Has University Department of Psychology Kadir Has Cad., Cibali Fatih, 34083 İstanbul – Turkey Email: [email protected] Tel: +90-212- 533 65 32 (1667 ext.) EDUCATION PhD - Cognitive Psychology (2012-2016) Koç University, Istanbul M.A. - Clinical Psychology (2009-2011) Doğuş University, Istanbul B.A. - Psychology, 2006-2009 Boğaziçi University, Istanbul, PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Assistant Professor (2017 - ) Kadir Has University, Department of Psychology Post-Doctoral Research Fellow (2016 – 2017) Koç University, Department of Psychology Research & Teaching Assistant (2012 – 2016) Koç University, Department of Psychology Visiting Researcher (2014 – 2015) Duke University, Department of Psychology Research Assistant (2009 –2012) Doğuş University, Department of Psychology Researcher (2010 – 2012) The role of adult attachment in communication patterns in dating adults Trainer (2010 – 2011) Effective parenting training for female inmates Trainer & Researcher (2010) Psychological assessment for substance-dependent inmates Researcher (2008 – 2009) Boğaziçi University, Adaptation of Attachment Q-Sort Researcher (2006 - 2007) Boğaziçi University, Cognitive assessment in preschool children PUBLICATIONS Öner, S. & Gülgöz, S. (in press). Otobiyografik hatırlamanın duygu düzenleme işlevi, Türk Psikoloji Dergisi. Ece, B., Öner, S., Demiray, B. & Gülgöz, S. (in press). Comparison of Earliest and Later Autobiographical Memories in Young and Middle-Aged Adults. Studies in Psychology Öner, S. (2017). Neural substrates of cognitive emotion regulation: A brief review. Psychiatry and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 28 (1), 91-96 Öner, S. & Gülgöz, S. (2017). Remembering successes and failures: rehearsal characteristics influence recollection and distancing. Journal of Cognitive Psychology, doi: 10.1080/20445911.2017.1406489. Öner, S. & Gülgöz, S. (2017). Autobiographical remembering regulates emotions: A functional perspective. Memory, doi: 10.1080/09658211.2017.1316510. -

Turkey: the World’S Earliest Cities & Temples September 14 - 23, 2013 Global Heritage Fund Turkey: the World’S Earliest Cities & Temples September 14 - 23, 2013

Global Heritage Fund Turkey: The World’s Earliest Cities & Temples September 14 - 23, 2013 Global Heritage Fund Turkey: The World’s Earliest Cities & Temples September 14 - 23, 2013 To overstate the depth of Turkey’s culture or the richness of its history is nearly impossible. At the crossroads of two continents, home to some of the world’s earliest and most influential cities and civilizations, Turkey contains multi- tudes. The graciousness of its people is legendary—indeed it’s often said that to call a Turk gracious is redundant—and perhaps that’s no surprise in a place where cultural exchange has been taking place for millennia. From early Neolithic ruins to vibrant Istanbul, the karsts and cave-towns of Cappadocia to metropolitan Ankara, Turkey is rich in treasure for the inquisi- tive traveler. During our explorations of these and other highlights of the coun- FEATURING: try, we will enjoy special access to architectural and archaeological sites in the Dan Thompson, Ph.D. company of Global Heritage Fund staff. Director, Global Projects and Global Heritage Network Dr. Dan Thompson joined Global Heritage Fund full time in January 2008, having previously conducted fieldwork at GHF-supported projects in the Mirador Basin, Guatemala, and at Ani and Çatalhöyük, both in Turkey. As Director of Global Projects and Global Heri- tage Network (GHN), he oversees all aspects of GHF projects at the home office, manages Global Heritage Network, acts as senior editor of print and web publica- tions, and provides support to fundraising efforts. Dan has BA degrees in Anthropology/Geography and Journalism, an MA in Near Eastern Studies from UC Berkeley, and a Ph.D. -

CONSTANTINOPLE COMPOSITE the PLEIADES PATTERN the 7 Hills of the Golden Horn by Luis B

CONSTANTINOPLE COMPOSITE THE PLEIADES PATTERN The 7 Hills of the Golden Horn by Luis B. Vega [email protected] www.PostScripts.org The purpose of this illustration is to suggest that the Golden Horn of the ancient city of Constantinople is configured to the Cydonia, Mars pyramid complex. The Martian motif consists of a 7 pyramid Pleiadian City, the giant Pentagon Pyramid and the Face of Mars or that of a supposed mausoleum to the demigod, Ala-lu. What is unique about this 2nd Roman Capital founded by the Emperor Constantine in 330 AD is that the breath of the Horn or peninsula is laid out in the approximate depiction of the Pleiades star cluster corresponding to the 7 hills of the Golden Horn. During the Roman and Byzantium periods, the 7 hills corresponded to various religious monasteries or churches as were with its twin capital of Rome with its 7 hills. The most prominent being the Hagia Sophia basilica or Holy Wisdom from the Greek. One of the main reasons the move of imperial capitals was made from Rome to Constantinople was because Rome was being sacked so many times by the northern Germanic tribes. Since the fall of Constantinople to the Muslims in 1453 the various churches have been converted into mosques. The name of Constantinople was changed to Istanbul by the Ottoman Turks who are Asiatic and used the Greek word for ‘The City’. The Golden Horn is in the European site of the Straits of the Bosphorus. The other celestial association with this Golden Horn is that it is referencing to the constellation of Taurus in which the Pleaides are situated. -

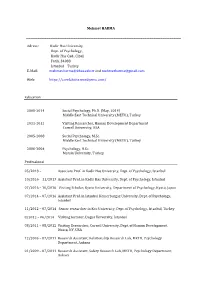

Mehmet HARMA Adress: Kadir Has University

Mehmet HARMA Adress: Kadir Has University Dept. of Psychology, Kadir Has Cad., Cibali Fatih, 34083 Istanbul – Turkey E-Mail: [email protected] and [email protected] Web: https://corelab.khas.edu.tr Education 2008-2014 Social Psychology, Ph.D. (May, 2014) Middle East Technical University (METU), Turkey 2011-2012 Visiting Researcher, Human Development Department Cornell University, USA 2005-2008 Social Psychology, M.Sc. Middle East Technical University (METU), Turkey 2000-2004 Psychology, B.Sc. Mersin University, Turkey Professional 05/2018 – Associate Prof. in Kadir Has University, Dept. of Psychology, Istanbul 10/2016 – 11/2017 Assistant Prof. in Kadir Has University, Dept. of Psychology, Istanbul 07/2016 – 10/2016 Visiting Scholar, Kyoto University, Department of Psychology, Kyoto, Japan 07/2014 – 07/2016 Assistant Prof. in Istanbul Kemerburgaz University, Dept. of Psychology, Istanbul 11/2012 – 07/2014 Senior researcher in Koc University, Dept. of Psychology, Istanbul, Turkey 8/2012 – 06/2014 Visiting lecturer, Dogus University, Istanbul 08/2011 – 08/2012 Visiting Researcher, Cornell University, Dept. of Human Development, Ithaca, NY, USA 12/2005 – 07/2011 Research Assistant, Relationship Research Lab, METU, Psychology Department, Ankara 01/2009 – 07/2011 Research Assistant, Safety Research Lab, METU, Psychology Department, Ankara 02/2010 – 07/2010 Teaching Assistant, METU Psychology Department, Advance d Design and Statistical Procedures in the Assessment of Psychological Change; Graduate Course 09/2009 – 01/2010 Teaching -

Journey to Turkey: a Survey of Culture, Economics and Politics of Turkey

IAS 3950.026 Journey to Turkey: A Survey of Culture, Economics and Politics of Turkey IAS 3950 Journey to Turkey: A Survey of Culture, Economics and Politics of Turkey Course duration: May 19 – June 6, 2015 Instructor: Firat Demir; Office: CCD1, Room: 436; Office hours: By appointment; Tel. 325-5844; E-mail: [email protected] 1. Course Objective The Anatolian Peninsula that connects Asia and Europe has been at the epicenter of many empires and civilizations for thousands of years. Any attempt to understand the culture, institutions and many of the current challenges present in modern Turkey should begin with the study of these civilizations, which have contributed immensely to the development of the Western and Asian civilizations. After all, this is the place where the words Asia and Europe were coined and where the very first monumental structures in history were built (Gobeklitepe, dating back to 10000 BC). Also, I should mention that the father of modern history, Herodotus was a native of Turkey (a title first conferred by Cicero). This course is comparative and interdisciplinary in nature and crosses multiple disciplines including arts, sociology, cultural studies, history, urban planning, economics, and politics. We will constantly compare and contrast the past and the present, East and the West, Turkey and Europe, modern and archaic, secular and religious, democratic and authoritarian, etc. A special attention will be paid to challenge students’ pre-conceived notions, opinions, perspectives and attitudes towards Western vs. Non-Western civilizations, particularly so for those involving the Middle East and Europe. During our journey, we will visit thousand + years old churches, synagogues, mosques, ancient temples, palaces, cities, monuments as well as the most exquisite examples of modern art, and perhaps not so exquisite examples of modern architecture. -

Mehmet HARMA Adress: Kadir Has University Dept

Mehmet HARMA Adress: Kadir Has University Dept. of Psychology, Kadir Has Cad., Cibali Fatih, 34083 Istanbul – Turkey E-Mail: [email protected] and [email protected] Web: https://corelabsite.wordpress.com/ Education 2008-2014 Social Psychology, Ph.D. (May, 2014) Middle East Technical University (METU), Turkey 2011-2012 Visiting Researcher, Human Development Department Cornell University, USA 2005-2008 Social Psychology, M.Sc. Middle East Technical University (METU), Turkey 2000-2004 Psychology, B.Sc. Mersin University, Turkey Professional 05/2018 – Associate Prof. in Kadir Has University, Dept. of Psychology, Istanbul 10/2016 – 11/2017 Assistant Prof. in Kadir Has University, Dept. of Psychology, Istanbul 07/2016 – 10/2016 Visiting Scholar, Kyoto University, Department of Psychology, Kyoto, Japan 07/2014 – 07/2016 Assistant Prof. in Istanbul Kemerburgaz University, Dept. of Psychology, Istanbul 11/2012 – 07/2014 Senior researcher in Koc University, Dept. of Psychology, Istanbul, Turkey 8/2012 – 06/2014 Visiting lecturer, Dogus University, Istanbul 08/2011 – 08/2012 Visiting Researcher, Cornell University, Dept. of Human Development, Ithaca, NY, USA 12/2005 – 07/2011 Research Assistant, Relationship Research Lab, METU, Psychology Department, Ankara 01/2009 – 07/2011 Research Assistant, Safety Research Lab, METU, Psychology Department, Ankara 02/2010 – 07/2010 Teaching Assistant, METU Psychology Department, Advance d Design and Statistical Procedures in the Assessment of Psychological Change; Graduate Course 09/2009 – 01/2010 -

Cagaloglu Hamam 46 Ecumenical Patriarchate

THIS SIDE OF THES GOLDEN Yerebatan Cistern 44 Spiritual brothers: The HORN: THE OLD TOWN AND Cagaloglu Hamam 46 Ecumenical Patriarchate EYUP 8 Nuruosmaniye Mosque 48 of Constantinople 84 Topkapi Palace 10 Grand Bazaar 50 Fethiye Mosque (Pamma- The Power and the Glory Knotted or woven: The Turkish karistos Church) 86 of the Ottoman Rulers: art of rug-making 52 Chora Church 88 Inside the Treasury 12 Book Bazaar 54 Theodosian City Wall 90 The World behind the Veil: Traditional handicrafts: Eyiip Sultan Mosque 92 Life in the Harem 14 Gold and silver jewelry 56 Santralistanbul Center of Hagia Eirene 16 Beyazit Mosque 58 Art and Culture 94 Archaeological Museum 18 Siileymaniye Mosque 60 Fountain of Sultan Ahmed 20 Rustem Pa§a Mosque 64 BEYOND THE GOLDEN Hagia Sophia 22 Egyptian Bazaar HORN:THE NEWTOWN Constantine the Great 26 (Spice Bazaar) 66 AND THE EUROPEAN SIDE Sultan Ahmed Mosque Yeni Mosque, OF THE BOSPHORUS 96 (Blue Mosque) 28 Hiinkar Kasri 68 Karakoy (Galata), Tophane 98 Arasta Bazaar 32 Port of Eminonii 70 Jewish life under the The Great Palace of the Galata Bridge 72 Crescent Moon 100 Byzantine Emperors, Myths and legends: The Istanbul Modern Museum 102 Mosaic Museum 34 story(ies) surrounding Shooting stars above the Istanbul's Traditional the Golden Horn 74 gilded cage of art: Wooden Houses and Sirkeci train station 76 Istanbul Biennal 104 the Ravages of Time 36 $ehzade Mosque Kilig Ali Pa§a Mosque, The Hippodrome 38 (Prince's Mosque) 78 Nusretiye Mosque 106 Sokollu Mehmet Pa§a Valens Aqueduct 80 Galata Tower 108 Mosque 40 Fatih -

Refik Anadol CV Eng

REFİK ANADOL 1985 Istanbul, Turkey Lives and works in Los Angeles, CA, USA SELECTED EXHIBITIONS 2021 Machine Memoirs: Space, Pilevneli Gallery, Istanbul, Turkey 2019 Machine Hallucination, Artechouse, New York City, USA Latent History, Fotografiska, Stockholm, Sweden Infinite Space, Artechouse, Washington, DC, USA Macau Currents: Data Paintings, Art Macao: International Art Exhibition, Macao, China Archive Dreaming, Symbiosis – Asia Digital Art Exhibition, Beijing, China Machine Hallucination – Study II, Hermitage Museum, Moscow, Russia Memoirs from Latent Space, New Human Agenda, Akbank Sanat, Istanbul, Turkey Melting Memories – Engram – LEV Festival, Gijón, Spain Machine Hallucination – Study I, Bitforms Gallery, Los Angeles, CA, USA Infinity Room / New Edition, ZKM, Karlsruhe, Germany Bosphorus, At The Factory: 10 Artists / 10 Individual Practices PİLEVNELİ Mecidiyeköy, Istanbul, Turkey Infinity Room / New Edition, Wood Street Gallery, Pittsburgh, PA, USA 2018 WDCH Dreams, Walt Disney Concert Hall, Los Angeles, California Melting Memories, PİLEVNELİ Dolapdere, Istanbul, Turkey Infinity Room/New Edition, New Zealand Festival, Wellington, New Zealand Virtual Archive, SALT Galata, Istanbul, Turkey Liminality V1.0, International Art Projects, Hildesheim, Germany Infinity Room / New Edition, Kaneko Museum, Omaha, Nebraska The Invisible Body : Data Paintings, Sven-Harrys Museum, Stockholm, Sweden Data Sculpture Series, Art Center Nabi, Seoul, South Korea 1-2-3 Data Exhibition, Paris, EDF, France Infinity Room, Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary -

![Fall of Constantinople] Pmunc 2018 Contents](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3444/fall-of-constantinople-pmunc-2018-contents-1093444.webp)

Fall of Constantinople] Pmunc 2018 Contents

[FALL OF CONSTANTINOPLE] PMUNC 2018 CONTENTS Letter from the Chair and CD………....…………………………………………....[3] Committee Description…………………………………………………………….[4] The Siege of Constantinople: Introduction………………………………………………………….……. [5] Sailing to Byzantium: A Brief History……...………....……………………...[6] Current Status………………………………………………………………[9] Keywords………………………………………………………………….[12] Questions for Consideration……………………………………………….[14] Character List…………………...………………………………………….[15] Citations……..…………………...………………………………………...[23] 2 [FALL OF CONSTANTINOPLE] PMUNC 2018 LETTER FROM THE CHAIR Dear delegates, Welcome to PMUNC! My name is Atakan Baltaci, and I’m super excited to conquer a city! I will be your chair for the Fall of Constantinople Committee at PMUNC 2018. We have gathered the mightiest commanders, the most cunning statesmen and the most renowned scholars the Ottoman Empire has ever seen to achieve the toughest of goals: conquering Constantinople. This Sultan is clever and more than eager, but he is also young and wants your advice. Let’s see what comes of this! Sincerely, Atakan Baltaci Dear delegates, Hello and welcome to PMUNC! I am Kris Hristov and I will be your crisis director for the siege of Constantinople. I am pleased to say this will not be your typical committee as we will focus more on enacting more small directives, building up to the siege of Constantinople, which will require military mobilization, finding the funds for an invasion and the political will on the part of all delegates.. Sincerely, Kris Hristov 3 [FALL OF CONSTANTINOPLE] PMUNC 2018 COMMITTEE DESCRIPTION The year is 1451, and a 19 year old has re-ascended to the throne of the Ottoman Empire. Mehmed II is now assembling his Imperial Court for the grandest city of all: Constantinople! The Fall of Constantinople (affectionately called the Conquest of Istanbul by the Turks) was the capture of the Byzantine Empire's capital by the Ottoman Empire. -

TURKEY Threats to the World Heritage in the Changing Metropolitan Areas of Istanbul

Turkey 175 TURKEY Threats to the World Heritage in the Changing Metropolitan Areas of Istanbul The Historic Areas of Istanbul on the Bosporus peninsula were in- scribed in 1985 in the World Heritage List, not including Galata and without a buffer zone to protect the surroundings. Risks for the historic urban topography of Istanbul, especially by a series of high- rise buildings threatening the historic urban silhouette, were already presented in Heritage at Risk 2006/2007 (see the visual impact as- sessment study by Astrid Debold-Kritter on pp. 159 –164). In the last years, dynamic development and transformation have changed the metropolitan areas with a new scale of building inter- ventions and private investments. Furthermore, the privatisation of urban areas and the development of high-rise buildings with large ground plans or in large clusters have dramatically increased. orld eritagea,,eerules and standards set upby arely knownconveyrthe ap- provedConflicts in managing the World Heritage areas of Istanbul Metropolis derive from changing the law relevant for the core area- sisthe . Conservation sites and areas of conservation were proposed in 1983. In 1985, the historic areas of Istanbul were inscribed on the basis of criteria 1 to 4. The four “core areas”, Archaeological Park, Süleymaniye conservation site, Zeyrek conservation site, and the Theodosian land walls were protected by Law 2863, which in Article I (4) gives a definition of “conservation” and of “areas of conservation”. Article II defines right and responsibility: “cultural and natural property cannot be acquired through possession”; article Fig. 1. Project for Diamond of Dubai, 2010, height 270 m, 53 floors, Hattat 17 states that “urban development plans for conservation” have to Holding Arch.