Russian-Japanese Relatio Ns W Hat Role for the Far Ea St

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

James Rowson Phd Thesis Politics and Putinism a Critical Examination

Politics and Putinism: A Critical Examination of New Russian Drama James Rowson A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Royal Holloway, University of London Department of Drama, Theatre & Dance September 2017 1 Declaration of Authorship I James Rowson hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: ______________________ Date: ________________________ 2 Abstract This thesis will contextualise and critically explore how New Drama (Novaya Drama) has been shaped by and adapted to the political, social, and cultural landscape under Putinism (from 2000). It draws on close analysis of a variety of plays written by a burgeoning collection of playwrights from across Russia, examining how this provocative and political artistic movement has emerged as one of the most vehement critics of the Putin regime. This study argues that the manifold New Drama repertoire addresses key facets of Putinism by performing suppressed and marginalised voices in public arenas. It contends that New Drama has challenged the established, normative discourses of Putinism presented in the Russian media and by Putin himself, and demonstrates how these productions have situated themselves in the context of the nascent opposition movement in Russia. By doing so, this thesis will offer a fresh perspective on how New Drama’s precarious engagement with Putinism provokes political debate in contemporary Russia, and challenges audience members to consider their own role in Putin’s autocracy. The first chapter surveys the theatrical and political landscape in Russia at the turn of the millennium, focusing on the political and historical contexts of New Drama in Russian theatre and culture. -

Final List of Participants

OSCE Copenhagen Anniversary Conference on "20 years of the OSCE Copenhagen Document: Status and future perspectives" FINAL LIST OF PARTICIPANTS Copenhagen, 10 - 11 June 2010 OSCE Delegations / Partners for Co-operation Albania Mr. Albjon BOGDANI Ministry of Foreign Affairs OSCE Sector, Specialist Blvd. "Gjergj Fishta" 6; Tirana; Albania E-Mail: [email protected] Tel:+355-42-364 090 Ext. 186 Fax:+355-42-364 2085 Germany Mr. Markus LOENING Federal Foreign Office Federal Government Commissioner for Human Rights Policy and Auswaertiges Amt, Section 203; Werderscher Markt 1; D-10117 Berlin; Humanitarian Aid Germany Mr. Peter KETTNER Federal Foreign Office First Secretary Auswaertiges Amt, Section 203; Werderscher Markt 1; D-10117 Berlin; Germany Dr. Lorenz BARTH Permanent Mission of the Federal Republic of Germany to the OSCE Counsellor Metternichgasse 3; 1030 Vienna; Austria E-Mail: [email protected] Tel:+43-1-711 54 190 Fax:+43-1-711 54 268 Website: http://www.osze.diplo.de United States of America Dr. Michael HALTZEL United States Mission to the OSCE Head of Delegation Obersteinergasse 11/1; 1190 Vienna; Austria E-Mail: [email protected] Tel:+1-202-736 74 45 Fax:+1-202-647 13 69 Website: http://osce.usmission.gov Amb. Ian KELLY United States Mission to the OSCE United States Permanent Representative to the OSCE Obersteinergasse 11/1; 1190 Vienna; Austria E-Mail: [email protected] Tel:+43-1-313 39 34 01 Fax:+43-1-368 31 53 Website: http://osce.usmission.gov Ms. Carol FULLER United States Mission to the OSCE Deputy Chief of Mission Obersteinergasse 11/1; 1190 Vienna; Austria E-Mail: [email protected] Tel:+43-1-313 39 34 02 Website: http://osce.usmission.gov Mr. -

Company News SECURITIES MARKET NEWS

SSEECCUURRIIITTIIIEESS MMAARRKKEETT NNEEWWSSLLEETTTTEERR weekly Presented by: VTB Bank, Custody April 5, 2018 Issue No. 2018/12 Company News Commercial Port of Vladivostok’s shares rise 0.5% on April 3, 2018 On April 3, 2018 shares of Commercial Port of Vladivostok, a unit of Far Eastern Shipping Company (FESCO) of Russian multi-industry holding Summa Group, rose 0.48% as of 10.12 a.m. Moscow time after a 21.72% slump on April 2. On March 31, the Tverskoi District Court of Moscow sanctioned arrest of brothers Ziyavudin and Magomed Magomedov, co-owners of Summa Group, on charges of RUB 2.5 bln embezzlement. It also arrested Artur Maksidov, CEO of Summa’s construction subsidiary Inteks, on charges of RUB 669 mln embezzlement. On April 2, shares of railway container operator TransContainer, in which FESCO owns 25.07%, fell 0.4%, and shares of Novorossiysk Commercial Sea Port (NCSP), in which Summa and oil pipeline monopoly Transneft own 50.1% on a parity basis, lost 1.61%. Cherkizovo plans common share SPO, to change dividends policy On April 3, 2018 it was reported that meat producer Cherkizovo Group would hold a secondary public offering (SPO) of common shares on the Moscow Exchange to raise USD 150 mln and change the dividend policy to pay 50% of net profit under International Financial Reporting Standards. The shares grew 1.67% to RUB 1,220 as of 10:25 a.m., Moscow time, on the Moscow Exchange. Under the proposal, the current shareholders, including company MB Capital Europe Ltd, whose beneficiaries are members of the Mikhailov- Babayev family (co-founders of the group), will sell shares. -

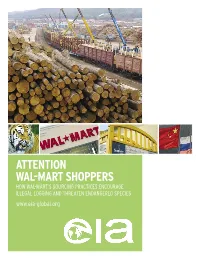

Attention Wal-Mart Shoppers How Wal-Mart’S Sourcing Practices Encourage Illegal Logging and Threaten Endangered Species Contents © Eia

ATTENTION WAL-MART SHOPPERS HOW WAL-MART’S SOURCING PRACTICES ENCOURAGE ILLEGAL LOGGING AND THREATEN ENDANGERED SPECIES www.eia-global.org CONTENTS © EIA ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Copyright © 2007 Environmental Investigation Agency, Inc. No part of this publication may be 2 INTRODUCTION: WAL-MART IN THE WOODS reproduced in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the Environmental 4 THE IMPACTS OF ILLEGAL LOGGING Investigation Agency, Inc. Pictures on pages 8,10,11,14,15,16 were published in 6 LOW PRICES, HIGH CONTROL: WAL-MART’S BUSINESS MODEL The Russian Far East, A Reference Guide for Conservation and Development, Josh Newell, 6 REWRITING THE RULES OF THE SUPPLIER-RETAILER RELATIONSHIP 2004, published by Daniel & Daniel, Publishers, Inc. 6 SQUEEZING THE SUPPLY CHAIN McKinleyville, California, 2004. ENVIRONMENTAL INVESTIGATION AGENCY 7 BIG FOOTPRINT, BIG PLANS: WAL-MART’S ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT 7 THE FOOTPRINT OF A GIANT PO Box 53343, Washington DC 20009, USA 7 STEPS FORWARD Tel: +1 202 483 6621 Fax: +1 202 986 8626 Email: [email protected] 8 GLOBAL REACH: WAL-MART’S SALE OF WOOD PRODUCTS Web: www.eia-global.org 8 A SNAPSHOT INTO WAL-MART’S WOOD BUYING AND RETAIL 62-63 Upper Street, London N1 ONY, UK 8 WAL-MART AND CHINESE EXPORTS 8 THE RISE OF CHINA’S WOOD PRODUCTS INDUSTRY Tel: +44(0)20 7354 7960 Fax: +44(0)20 7354 7961 10 CHINA IMPORTS RUSSIA’S GREAT EASTERN FORESTS Email: [email protected] 10 THE WILD WILD FAR EAST 11 CHINA’S GLOBAL SOURCING Web: www.eia-international.org 10 IRREGULARITIES FROM FOREST TO FRONTIER 14 ECOLOGICAL AND SOCIAL IMPACTS 15 THE FLOOD OF LOGS ACROSS THE BORDER 17 LONGJIANG SHANGLIAN: BRIEFCASES OF CASH FOR FORESTS 18 A LANDSCAPE OF WAL-MART SUPPLIERS: INVESTIGATION CASE STUDIES 18 BABY CRIBS 18 DALIAN HUAFENG FURNITURE CO. -

Businessmen V. Investigators: Who Is Responsible for the Poor Russian Investment Climate?

BUSINESSMEN V. INVESTIGATORS: WHO IS ReSPONSIBLE FOR THE POOR RUSSIAN INVESTMENT CLIMATE? Dmitry Gololobov, University of Westminster (London, UK) This article aims to examine the extent to which Russian investigations into economic and financial crimes are influenced by such factors as systemic problems with Russian gatekeepers, the absence of a formal corporate whistle-blowing mechanism and the continuous abuse of the law by the Russian business community. The traditional critical approach to the quality and effectiveness of Russian economic and financial investigations does not produce positive results and needs to be reformulated by considering the opinions of entrepreneurs. The author considers that forcing Russian entrepreneurs, regardless of the size of their business, to comply with Russian laws and regulations may be a more efficient way to develop the business environment than attempting to gradually improve the Russian judicial system. It is also hardly possible to expect the Russian investigatory bodies to investigate what are effectively complex economic and financial crimes in the almost complete absence of a developed whistle-blowing culture. Such a culture has greatly contributed to the success of widely-publicised corporate and financial investigations in the United States and Europe. The poor development of the culture of Russian gatekeepers and the corresponding regulatory environment is one more significant factor that permanently undermines the effectiveness of economic investigations and damages the investment climate. Key words: Russia; investigation; economic crime; gatekeepers; whistleblowing. 1. Introduction The aim of this article is to analyse the ongoing conflict between Russian investigators and the Russian business community, and to make one more attempt at answering the long-standing question regarding how a satisfactory balance between the interests of effective investigation and the protection of the business community can be reached. -

Catalogue of Exporters of Primorsky Krai № ITN/TIN Company Name Address OKVED Code Kind of Activity Country of Export 1 254308

Catalogue of exporters of Primorsky krai № ITN/TIN Company name Address OKVED Code Kind of activity Country of export 690002, Primorsky KRAI, 1 2543082433 KOR GROUP LLC CITY VLADIVOSTOK, PR-T OKVED:51.38 Wholesale of other food products Vietnam OSTRYAKOVA 5G, OF. 94 690001, PRIMORSKY KRAI, 2 2536266550 LLC "SEIKO" VLADIVOSTOK, STR. OKVED:51.7 Other ratailing China TUNGUS, 17, K.1 690003, PRIMORSKY KRAI, VLADIVOSTOK, 3 2531010610 LLC "FORTUNA" OKVED: 46.9 Wholesale trade in specialized stores China STREET UPPERPORTOVA, 38- 101 690003, Primorsky Krai, Vladivostok, Other activities auxiliary related to 4 2540172745 TEK ALVADIS LLC OKVED: 52.29 Panama Verkhneportovaya street, 38, office transportation 301 p-303 p 690088, PRIMORSKY KRAI, Wholesale trade of cars and light 5 2537074970 AVTOTRADING LLC Vladivostok, Zhigura, 46 OKVED: 45.11.1 USA motor vehicles 9KV JOINT-STOCK COMPANY 690091, Primorsky KRAI, Processing and preserving of fish and 6 2504001293 HOLDING COMPANY " Vladivostok, Pologaya Street, 53, OKVED:15.2 China seafood DALMOREPRODUKT " office 308 JOINT-STOCK COMPANY 692760, Primorsky Krai, Non-scheduled air freight 7 2502018358 OKVED:62.20.2 Moldova "AVIALIFT VLADIVOSTOK" CITYARTEM, MKR-N ORBIT, 4 transport 690039, PRIMORSKY KRAI JOINT-STOCK COMPANY 8 2543127290 VLADIVOSTOK, 16A-19 KIROV OKVED:27.42 Aluminum production Japan "ANKUVER" STR. 692760, EDGE OF PRIMORSKY Activities of catering establishments KRAI, for other types of catering JOINT-STOCK COMPANY CITYARTEM, STR. VLADIMIR 9 2502040579 "AEROMAR-ДВ" SAIBEL, 41 OKVED:56.29 China Production of bread and pastry, cakes 690014, Primorsky Krai, and pastries short-term storage JOINT-STOCK COMPANY VLADIVOSTOK, STR. PEOPLE 10 2504001550 "VLADHLEB" AVENUE 29 OKVED:10.71 China JOINT-STOCK COMPANY " MINING- METALLURGICAL 692446, PRIMORSKY KRAI COMPLEX DALNEGORSK AVENUE 50 Mining and processing of lead-zinc 11 2505008358 " DALPOLIMETALL " SUMMER OCTOBER 93 OKVED:07.29.5 ore Republic of Korea 692183, PRIMORSKY KRAI KRAI, KRASNOARMEYSKIY DISTRICT, JOINT-STOCK COMPANY " P. -

Russian M&A Review 2017

Russian M&A review 2017 March 2018 KPMG in Russia and the CIS kpmg.ru 2 Russian M&A review 2017 Contents page 3 page 6 page 10 page 13 page 28 page 29 KEY M&A 2017 OUTLOOK DRIVERS OVERVIEW IN REVIEW FOR 2018 IN 2017 METHODOLOGY APPENDICES — Oil and gas — Macro trends and medium-term — Financing – forecasts sanctions-related implications — Appetite and capacity for M&A — Debt sales market — Cross-border M&A highlights — Sector highlights © 2018 KPMG. All rights reserved. Russian M&A review 2017 3 Overview Although deal activity increased by 13% in 2017, the value of Russian M&A Deal was 12% lower than the previous activity 13% year, at USD66.9 billion, mainly due to an absence of larger deals. This was in particular reflected in the oil and gas sector, which in 2016 was characterised by three large deals with a combined value exceeding USD28 billion. The good news is that investors have adjusted to the realities of sanctions and lower oil prices, and sought opportunities brought by both the economic recovery and governmental efforts to create a new industrial strategy. 2017 saw a significant rise in the number and value of deals outside the Deal more traditional extractive industries value 37% and utility sectors, which have historically driven Russian M&A. Oil and gas sector is excluded If the oil and gas sector is excluded, then the value of deals rose by 37%, from USD35.5 billion in 2016 to USD48.5 billion in 2017. USD48.5bln USD35.5bln 2016 2017 © 2018 KPMG. -

Russian Federation As Central Planner: Case Study of Investments Into the Russian Far East in Anticipation of the 2012 Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation Conference

Russian Federation as Central Planner: Case Study of Investments into the Russian Far East in Anticipation of the 2012 Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation Conference Anne Thorsteinson A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in International Studies: Russia, East Europe and Central Asia University of Washington 2012 Committee: Judith Thornton, Chair Craig ZumBrunnen Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Jackson School of International Studies TABLE OF CONTENTS Page List of Figures ii List of Tables iii Introduction 1 Chapter 1: An Economic History of the Russian Far East 6 Chapter 2: Primorsky Krai Today 24 Chapter 3: The Current Federal Reform Program 30 Chapter 4: Economic Indicators in Primorsky Krai 43 Chapter 5: Conclusion 54 Bibliography 64 LIST OF FIGURES Page 1. Primorsky Krai: Sown Area of Crops 21 2. Far East Federal Region: Sown Area of Crops 21 3. Primorye Agricultural Output 21 4. Russian Federal Fisheries Production 22 5. Vladivostok: Share of Total Exports by Type, 2010 24 6. Vladivostok: Share of Total Imports by Type, 2010 24 7. Cost of a Fixed Basket of Consumer Goods and Services as a Percentage of the All Russian Average 43 8. Cost of a Fixed Basked of Consumer Goods and Services 44 9. Per Capita Monthly Income 45 10. Per Capita Income in Primorsky Krai as a Percentage of the All Russian Average 45 11. Foreign Direct Investment in Primorsky Krai 46 12. Unemployed Proportion of Economically Active Population in Primorsky Krai 48 13. Students in State Institutions of Post-secondary Education in Primorsky Krai 51 14. -

Company News SECURITIES MARKET NEWS

SSEECCUURRIIITTIIIEESS MMAARRKKEETT NNEEWWSSLLEETTTTEERR weekly Presented by: VTB Bank, Custody December 27, 2018 Issue No. 2018/49 VTB Bank Custody wishes you a happy and prosperous 2019 New Year full of success, wealth and joy! Let all your dreams come true! Company News Government may consider EDC-Schlumberger deal in January-February 2019 On December 20, 2018 Andrei Tsyganov, Deputy Director of the Federal Antimonopoly Service, said that the Russian government’s commission for foreign investment control might consider an acquisition by U.S. oilfield servicing giant Schlumberger of a stake in Eurasia Drilling Company (EDC) in January-February. When asked about the date of the commission’s meeting where the EDC-Schlumberger deal might be discussed, he said that in January or in February. In July 2017, EDC’s shareholders approved the sale of a 51% stake in the company to Schlumberger. In November, the Federal Antimonopoly Service’s Deputy Director Andrei Tsyganov said that the service and Schlumberger were working on a mechanism to protect the company’s investment in EDC and Russian economic interests in case of new Western sanctions. In April 2018, Russian government’s commission for foreign investment control preliminarily approved Schlumberger’s bid to acquire between 25% plus one share and 49% in EDC. Promsvyazbank files RUB 282 bln suit versus former owners On December 21, 2018 it was reported that Russia’s Promsvyazbank filed RUB 282 bln suit against former executives and top managers of the bank and former beneficiary owners brothers Dmitry and Alexei Ananyev to the Moscow Arbitration Court. Promsvyazbank filed a suit to the Moscow Arbitration Court seeking redemption of losses from individuals who controlled the bank before December 15, 2017 - Dmitry and Alexei Ananyev - and against members of the management board, top managers, and executives that signed loss-making deals on behalf of the bank. -

History of Badminton

Facts and Records History of Badminton In 1873, the Duke of Beaufort held a lawn party at his country house in the village of Badminton, Gloucestershire. A game of Poona was played on that day and became popular among British society’s elite. The new party sport became known as “the Badminton game”. In 1877, the Bath Badminton Club was formed and developed the first official set of rules. The Badminton Association was formed at a meeting in Southsea on 13th September 1893. It was the first National Association in the world and framed the rules for the Association and for the game. The popularity of the sport increased rapidly with 300 clubs being introduced by the 1920’s. Rising to 9,000 shortly after World War Π. The International Badminton Federation (IBF) was formed in 1934 with nine founding members: England, Ireland, Scotland, Wales, Denmark, Holland, Canada, New Zealand and France and as a consequence the Badminton Association became the Badminton Association of England. From nine founding members, the IBF, now called the Badminton World Federation (BWF), has over 160 member countries. The future of Badminton looks bright. Badminton was officially granted Olympic status in the 1992 Barcelona Games. Indonesia was the dominant force in that first Olympic tournament, winning two golds, a silver and a bronze; the country’s first Olympic medals in its history. More than 1.1 billion people watched the 1992 Olympic Badminton competition on television. Eight years later, and more than a century after introducing Badminton to the world, Britain claimed their first medal in the Olympics when Simon Archer and Jo Goode achieved Mixed Doubles Bronze in Sydney. -

Pierce-The American College of Greece Model United Nations | 2019

Pierce-The American College of Greece Model United Nations | 2019 Committee: Special Political and Decolonization Committee Issue: The issue of the South Kuril Islands Student Officer: Marianna Generali Position: Co-Chair PERSONAL INTRODUCTION Dear Delegates, My name is Marianna Generali and I am a student in the 11th grade of HAEF Psychiko College. This year’s ACGMUN will be my first time chairing and my 9th conference overall. It is my honour to be serving as a co-chair in the Special Political and Decolonization Committee in the 3rd session of the ACGMUN. I am more than excited to work with each of you individually and I look forward to our cooperation within the committee. MUN is an extracurricular activity that I enjoy wholeheartedly and could not imagine my life without it. Through my MUN experience, I have gained so much and it has helped me in so many areas of my life. In particular, I have gained organizing and public speaking skills and enhanced my knowledge on the history of the world and most importantly current affairs, hence I believe this is a one of a kind opportunity and I hope that everyone will have a fruitful debate and a lot of fun. I hope that I can help you with your preparation and your work within the conference and in your endeavours overall. I believe this is a really interesting topic and will bring a lot of fruitful debate, but it is crucial that you come prepared. I will be the expert chair on the topic of the issue of the South Kuril Islands. -

Information for Persons Who Wish to Seek Asylum in the Russian Federation

INFORMATION FOR PERSONS WHO WISH TO SEEK ASYLUM IN THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION “Everyone has the right to seek and to enjoy in the other countries asylum from persecution”. Article 14 Universal Declaration of Human Rights I. Who is a refugee? According to Article 1 of the Federal Law “On Refugees”, a refugee is: “a person who, owing to well‑founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of particular social group or politi‑ cal opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country”. If you consider yourself a refugee, you should apply for Refugee Status in the Russian Federation and obtain protection from the state. If you consider that you may not meet the refugee definition or you have already been rejected for refugee status, but, nevertheless you can not re‑ turn to your country of origin for humanitarian reasons, you have the right to submit an application for Temporary Asylum status, in accordance to the Article 12 of the Federal Law “On refugees”. Humanitarian reasons may con‑ stitute the following: being subjected to tortures, arbitrary deprivation of life and freedom, and access to emergency medical assistance in case of danger‑ ous disease / illness. II. Who is responsible for determining Refugee status? The responsibility for determining refugee status and providing le‑ gal protection as well as protection against forced return to the country of origin lies with the host state. Refugee status determination in the Russian Federation is conducted by the Federal Migration Service (FMS of Russia) through its territorial branches.