Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HUSKERS HOST WORLD's Largest Tailgate THIS WEEKEND 2014 NEBRASKA SCHEDULE

NEBRASKA SOFTBALL NEBRASKANO. 1 IN SOFTBALL ACADEMIC ALL-AMERICANS • NO. 13 IN NCAA TOURNAMENT WINS NO. 10 IN WORLD SERIES APPEARANCES • NO. 10 IN NCAA TOURNAMENT APPEARANCES SOFTBALL MEDIA RELATIONS CONTACT: MATT SMITH OFFICE PHONE: (402) 472-7780 CELL PHONE: (402) 770-5926 E-MAIL: [email protected] WEEK 11: 2014 NEBRASKA SCHEDULE (30-13) Date Opponent Time/Result vs. OHIO STATE Hotel Encanto Invitational (Las Cruces, N.M.) Dates: Fri., Sat. & Sun., April 18, 19 & 20 Feb. 7 vs. UTEP W, 7-0 First Pitches: 6 p.m, 1 p.m. & Noon Feb. 7 vs. No. 12 Florida State W, 4-3 Ohio State Buckeyes Location: Lincoln, Neb. Nebraska Cornhuskers Feb. 8 at New Mexico State W, 11-0 (5) Record: 20-20 Stadium: Bowlin Stadium Record: 30-13 Feb. 9 vs. No. 12 Florida State L, 1-5 Ranking: NR/NR Live Stats & Audio: Huskers.com Rankings: 19th/20th Hilton Houston Plaza Classic (Houston, Texas) Big Ten Record: 6-6 Live TV: None Big Ten Record: 8-4 Feb. 14 at Houston W, 4-1 Feb. 14 vs. Army W, 7-0 BTN.com (Friday & Saturday) Away Record: 2-7 Live Streaming: Home Record: 7-3 Feb. 15 vs. Stephen F. Austin L, 0-1 Feb. 15 vs. Sam Houston State W, 2-0 HUSKERS HOST WORLD’S LARGEST TAILGate THIS WEEKEND Feb. 16 vs. Sam Houston State W, 7-1 The 19th-ranked Nebraska softball team wraps up an eight-game homestand this weekend by Mary Nutter Collegiate Classic (Cathedral City, Calif.) welcoming the Ohio State Buckeyes to Bowlin Stadium for a three-game series on Friday, Saturday and Feb. -

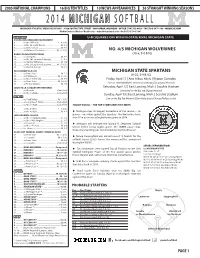

Week 10.1 MSU 2014.Indd

2005 NATIONAL CHAMPIONS 16 BIG TEN TITLES 10 WCWS APPEARANCES 36 STRAIGHT WINNING SEASONS 2005 NATIONAL CHAMPIONS 16 BIG TEN TITLES 10 WCWS APPEARANCES 36 STRAIGHT WINNING SEASONS 2014 MICHIGAN SOFTBALL MICHIGAN ATHLETICS MEDIA RELATIONS • 1100 SOUTH STATE STREET • ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN • OFFICE (734) 763-4423 • FAX (734) 647-1188 • MGOBLUE.COM Media Contact: Michael Kasiborski • [email protected] • Desk (734) 764-7881 FEBRUARY U-m SQUARES OFF WITH in-sTATE RIVAL MICHIGAN STATE USF WILSON-DEMARINI TOURNAMENT 8 . vs . No . 4 Florida . L, 4-9 (8) 8 . at No . 25 South Florda . W, 3-2 9 . vs . Illinois State . W, 7-1 9 . vs . Bethune-Cookman . W, 12-1 (5) NO. 4/5 MICHIGAN WOLVERINES RAGIN’ CAJUN INVITATIONAL (30-6, 9-0 B1G) 14 . vs . Memphis . W, 5-0 14 . at No . 20 Louisiana-Lafayette . L, 6-8 15 . vs . Central Arkansas . W, 7-0 15 . at No . 20 Louisiana-Lafayette . W, 15-1 (5) 16 . vs . Boston College . W, 6-5 FAU KICKOFF CLASSIC MICHIGAN STATE SPARTANS 21 . vs . Kent State . W, 7-1 21 . vs . Pittsburgh . W, 9-0 (5) (9-25, 2-9 B1G) 22 . vs . No . 5 Kentucky . W, 3-0 Friday, April 11 | Ann Arbor, Mich . | Wilpon Complex 22 . vs . Kent State . W, 1-0 (9) 23 . at Florida Atlantic . W, 1-0 Live on 1290 AM WLBY | Streamed on the Big Ten Digital Network LOUISVILLE SLUGGER INVITATIONAL Saturday, April 12 | East Lansing, Mich . | Secchia Stadium 28 . vs . Nevada . Cancelled Streamed on the Big Ten Digital Network 28 . vs . No . 5 UCLA . Cancelled Sunday, April 13 | East Lansing, Mich . -

Nomineesnominees 20132013 Jamesjames Beardbeard Foundationfoundation Bookbook Aawardswards for Cookbooks Published in English in 2012

2013 LIGHTS! JAMES CAMERA! BEARD TASTE! AWARDS SPOTLIGHT ON FOOD & FILM 20132013 JBFJBF AWARDAWARD NOMINEESNOMINEES 20132013 JAMESJAMES BEARDBEARD FOUNDATIONFOUNDATION BOOKBOOK AAWARDSWARDS for COOKBOOks PUBLISHED in ENGLISH in 2012. WINNERS WILL BE ANNOUNCED on MAy 3, 2013. AMERICAN COOKING Flour Water Salt Yeast: The Fundamentals of Artisan Bread and Pizza Fire in My Belly by Ken Forkish by Kevin Gillespie and David Joachim (Ten Speed Press) (Andrews McMeel Publishing) BEVERAGE Mastering the Art of Southern Cooking by Nathalie Dupree and Cynthia Graubart How to Love Wine: A Memoir and Manifesto (Gibbs Smith) by Eric Asimov (William Morrow) Southern Comfort: A New Take on the Recipes We Grew Up With Inventing Wine: A New History of One of the by Allison Vines-Rushing and Slade Rushing World’s Most Ancient Pleasures (Ten Speed Press) by Paul Lukacs (W.W. Norton & Company) BAKING AND DESSERTS Wine Grapes: A Complete Guide to 1,368 Vine Bouchon Bakery Varieties, Including Their Origins and Flavours by Thomas Keller and Sebastien Rouxel by Jancis Robinson, Julia Harding, and (Artisan) José Vouillamoz (Ecco) The Dahlia Bakery Cookbook: Sweetness in Seattle by Tom Douglas and Shelley Lance (William Morrow) 167 West 12th Street, New York, NY 10011 1 COOKING FROM A PROFESSIONAL What Katie Ate: Recipes and Other Bits & Pieces POINT OF VIEW by Katie Quinn Davies (Viking Studio) Come In, We’re Closed: An Invitation to Staff Meals at the World’s Best Restaurants INTERNATIONAL by Christine Carroll and Jody Eddy (Running Press) Burma: Rivers of Flavor by Naomi Duguid The Fundamental Techniques of Classic (Artisan) Italian Cuisine by The International Culinary Center, Cesare Casella, Gran Cocina Latina: The Food of Latin America and Stephanie Lyness by Maricel E. -

To the Create® Cooking Challenge 2017

Important Information: • Contest runs February 6–28, Contact: 2017. Jamie Haines • Winners will be announced American Public Television on or about May 8, 2017. [email protected] • Online submissions only! (617)338-4455 x. 129 CreateTV.com/challenge Submit Your Video “Audition” to the Create® Cooking Challenge 2017 Public television’s premier lifestyle channel to showcase up-and-coming culinary talent BOSTON (EMBARGOED UNTIL February 6, 2017) – Create TV today announces the launch of the Create Cooking Challenge 2017, the second year of a national video contest for both professional chefs and home cooks interested in winning a web series on CreateTV.com. Create is public television’s most-watched multicast channel, airing on 235 public TV stations and reaching 46 million viewers annually. Sponsored by American Public Television (APT), the Create Cooking Challenge runs February 6–28, 2017. Entrants must submit online a short (two minutes or less), original YouTube video featuring their best culinary project, recipe or tip. The contest will be judged by Create staff and a panel of public television chefs: Lidia Bastianich (Lidia’s Kitchen), Sara Moulton (Sara’s Weeknight Meals), Julia Collin Davison and Bridget Lancaster (co-hosts of America’s Test Kitchen and Cook’s Country), Kevin Belton (New Orleans Cooking With Kevin Belton), and Steven Raichlen (Steven Raichlen’s Project Smoke). The panel will judge submissions based on the entrant’s demonstrated culinary knowledge, ability to present ideas succinctly, overall telegenic appeal, uniqueness, and production values. A complete list of judging criteria is available on CreateTV.com/ challenge/rules. Last year’s Grand Prize winner, Jaime Isobe of Brooklyn, NY, was selected from more than 300 entries for his passion for cooking, stage presence and unique recipe, including multiple serving ideas. -

Simon Super Chefs Live! Returns for Encore Performance

Simon Super Chefs Live! Returns For Encore Performance March 30, 2005 Coast-to-Coast Tour Features Celebrity Chefs Alton Brown, Sara Moulton, Giada De Laurentiis, Jacques and Claudine Pepin and More Jacob's Creek, Bertolli, Dasani and KitchenAid to Serve as Major Sponsors INDIANAPOLIS, March 30 /PRNewswire-FirstCall/ -- Simon Brand Ventures (SBV), the business-to-consumer arm of Simon Property Group (NYSE: SPG), is sticking with its winning recipe and offering second helpings of Simon Super Chefs Live! -- a coast-to-coast mall tour that invites eager food fans across the country to get up close and personal with today's most popular TV chefs. The unique culinary experience feeds America's growing fascination with "food- as-entertainment" by offering exciting in-mall celebrations of food, wine, cooking and shopping. Kicking off April 2 in Orlando with Giada De Laurentiis, popular host of Everyday Italian on Food Network and author of a newly released cookbook by the same name, each stop will serve up a renowned celebrity chef as headliner. Other chef "stars" will include: * Alton Brown - author of several top-selling cookbooks and star of Good Eats as seen on Food Network, as well as co-host of Iron Chef America, also on Food Network * Nathalie Dupree - author of 10 cookbooks and host of more than 300 television shows that have aired on PBS, The Learning Channel and Food Network for over 15 years * Mary Ann Esposito - author of eight cookbooks and host of Ciao Italia, the longest running cooking series on PBS * Sara Moulton - cookbook author, -

Consumer PR Media Value

ASMI Consumer Public Relations FY13 Recap & FY14 Q1 Highlights" Alaska Seafood Marketing Institute! Board of Directors Meeting! October 28-30, 2013 Anchorage, Alaska! Consumer PR Media Value $20,000,000 $18,000,000 $16,000,000 $14,000,000 $12,000,000 $10,000,000 Investment $8,000,000 Media Value $6,000,000 $4,000,000 $2,000,000 $- FY09 FY10 FY11 FY12 FY13 FY13 Media Value: $18,160,000 2! Consumer PR Audience Impressions 600 500 400 300 200 100 0 FY09 FY10 FY11 FY12 FY13 FY14 Est. Audience Impressions (millions) FY13 Audience Impressions: 526,000,000 3! ASMI Consumer PR Program •" Goal: The Consumer PR program is designed to maintain the highest possible value perception for Alaska Seafood among American consumers. •" Objective: Continue to brand and effectively link Alaska’s unique position: wild, natural and sustainable seafood with superior taste and texture. •" Core Principle: ASMI conducts marketing activities that provide the largest economic benefit for its industry members. 4! Strategic Targeting The Consumer PR program targets both Baby Boomers and Gen Y (also called Millennials), to maximize funds spent and earn the highest return on investment. Due to size, Gen Y will overtake Boomers in spending power by 2017. Source: US Census Bureau 5! Consumers Seek Info Online ASMI’s consumer research shows the internet is the #1 source of information about seafood purchased for Gen Y, and #2 source for Boomers. Source: Illuminate for ASMI, 2012 6! Fish Where The Fish Are Food websites or blogs remain the top website cited by both Gen Y and Boomers as the top online source of seafood information. -

ON AIR, ONLINE, on the GO MEMBER GUIDE | NOVEMBER 2018 ADVERTISEMENT from the President Where to Tune In

Nova/Thai Cave Rescue | 15 Keepers of the Light | 16 WGBH News: The Scrum politics podcast | 26 ON AIR, ONLINE, ON THE GO MEMBER GUIDE | NOVEMBER 2018 ADVERTISEMENT From the President Where to Tune in Our Past, TV Our Future In November, we are celebrating Native American Heritage Month with pro- Digital broadcast FiOS RCN Cox Charter (Canada) Bell ExpressVu grams that give recognition to the significant contributions of America’s First Comcast Peoples, many of them calling Massachusetts their home. WGBH 2 2.1 2 2 2 2 2 284 Native America (page 14) challenges everything we thought we knew WGBH 2 HD 2.1 802 502 602 1002 782 819 about the Americas before and since contact with Europe. It travels through WGBX 44 44.1 16 44 14 804 21 n/a 15,000 years to showcase massive cities, unique systems of science, art and writing, and 100 million people connected WGBX 44 HD 44.1 801 544 n/a n/a n/a n/a by social networks and spiritual beliefs World 2.2 956 473 94 807 181 n/a spanning two continents. Create 44.3 959 474 95 805 182 n/a Made with the active participation of WGBH Kids 44.4 958 472 93 n/a 180 n/a Native American communities, this four- Boston Kids & n/a 22 n/a 3 n/a n/a n/a part series features sacred rituals filmed for Family (Boston only) the first time, history-changing scientific Channel numbers and availability may vary by community. Contact your provider for discoveries, and rarely heard voices from the more information. -

2018-19 Big Ten Records Book

2018-19 BIG TEN RECORDS BOOK Big Life. Big Stage. Big Ten. BIG TEN CONFERENCE RECORDS BOOK 2018-19 71st Edition FALL SPORTS Men’s Cross Country Women’s Cross Country Field Hockey Football* Men’s Soccer Women’s Soccer Volleyball WINTER SPORTS SPRING SPORTS Men's Basketball* Baseball Women's Basketball* Men’s Golf Men’s Gymnastics Women’s Golf Women’s Gymnastics Men's Lacrosse Men's Ice Hockey* Women's Lacrosse Men’s Swimming and Diving Rowing Women’s Swimming and Diving Softball Men’s Indoor Track and Field Men’s Tennis Women’s Indoor Track and Field Women’s Tennis Wrestling Men’s Outdoor Track and Field Women’s Outdoor Track and Field * Records appear in separate publication 4 CONFERENCE PERSONNEL HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS Faculty Representatives Basketball Coaches - Men’s 1991-1996 Lou Tepper 1896-1989 Henry H. Everett 1906 Elwood Brown 1997-2004 Ron Turner 1898-1899 Jacob K. Shell 1907 F.L. Pinckney 2005-2011 Ron Zook 1899-1906 Herbert J. Barton 1908 Fletcher Lane 2012-2016 Tim Beckman 1906-1929 George A. Goodenough 1909-1910 H.V. Juul 2017- Lovie Smith 1929-1936 Alfred C. Callen 1911-1912 T.E. Thompson 1936-1949 Frank E. Richart 1913-1920 Ralph R. Jones Golf Coaches - Men’s 1950-1959 Robert B. Browne 1921-1922 Frank J. Winters 1922-1923 George Davis 1959-1968 Leslie A. Bryan 1923-1936 J. Craig Ruby 1924 Ernest E. Bearg 1968-1976 Henry S. Stilwell 1937-1947 Douglas R. Mills 1925-1928 D.L. Swank 1976-1981 William A. -

Program Listings” (USPS Robert A

WXXI-TV/HD | WORLD | CREATE | AM1370 | CLASSICAL 91.5 | WRUR 88.5 | THE LITTLE | WXXI-KIDS PUBLIC TELEVISION & PUBLIC RADIO FOR ROCHESTER NOVEMBER 2019 SESAME STREET’S 50TH ANNIVERSARY CELEBRATION SUNDAY, NOVEMBER 17 AT 7PM ON WXXI-TV It’s an event 50 years in the making as Sesame Street celebrates its 50th Anniversary. We’re celebrating the world’s most iconic street with all our furry friends and some very special guests including Joseph Gordon-Levitt, Patti LaBelle, Sterling K. Brown, and many more! To mark the special event, the whole neighborhood comes together to take a photo under the Sesame Street sign—but the sign is missing! While Elmo and friends search for the sign, Joe takes a look back at 50 years of Sesame Street memories, and everyone soon realizes that Sesame Street isn’t just a sign or a street—it’s a place where everybody is welcome, learning is fun, and all kinds of monsters, birds, and humans come together to form lifelong friendships. Repeats 11/19 at 8 p.m. on WXXI-TV. THE LITTLE CONCERT SERIES PRESENTS: JOE LOCKE GIVING FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 22 AT 8PM DETAILS ON PAGE 18 >> THANKS! A CELEBRATION OF FALL, FOOD & GRATITUDE THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 28 AT 8AM ON CLASSICAL 91.5 DETAILS ON PAGE 16 >> AMERICA’S TEST KITCHEN TH 20 ANNIVERSARY SPECIAL SUNDAY, NOVEMBER 24 AT 8 P.M. ON WXXI-TV To celebrate 20 years of the most-watched cooking show on public television, America’s Test Kitchen fans around the country voted for their all-time favorite recipes from the series. -

Happy Campers Cozy Styles for Outdoor Fun Page 16

THRIVE • EMPOWER • SHINE WINTER 2016 FLOURISH ‘TIS THE SEASON’ YOUR HOLIDAY GUIDE FOR 2016 PAGE 45 HAPPY CAMPERS COZY STYLES FOR OUTDOOR FUN PAGE 16 ‘YOU’RE ALWAYS STRONGER THAN YOU THINK YOU ARE’. PAGE 28 TIME TO GIVE THANKS… Dr. JAYNE PATTY OUR PATIENTS If you KAREN ANDREA remember… Without you When gas was 55 cents our office a gallon, it’s time TAMMY REBECCA for a colonoscopy. doesn’t tick. WENDY CARRIE KATHY BRANDY CHERI Tis the season to stop the clock, reflect and 1429 North Mount Auburn Road give thanks to all whom God has blessed. Cape Girardeau, Missouri 63701 We are here to serve you. Call for an appointment. 573-334-8870 or 1-800-455-4888 2845 Professional Court | Cape Girardeau, MO 63703 Now in network with 573-334-5545 Anthem Pathway and Pathway X Jayne F. Scherrman, D.D.S. pediatricdentistrysemo.com 2 Flourish | winter 2016 www.semissourian.com/flourish www.semissourian.com/flourish winter 2016 | Flourish 3 contents FLOURISH from the editor ©2016 Southeast Missourian A Rust Communications publication 301 Broadway • PO Box 699 HAPPY Cape Girardeau, MO 63702-0699 saw a meme on Facebook today and I shared it on my CAMPERS page because it was funny, but also because it was so true in For subscription information, I my life. It said, “I stress about stress before there is even stress to call 800-879-1210 stress about because I’m stressed about the stress that I will inevitably or 573-335-6611 or online at have soon.” www.semissourian.com/flourish/ Anyone who knows me knows I worry about everything. -

Senate Approves Some Rate Relief

KEY LARGO 305.451.5700 make. MARATHON 305.743.4397 home. KEY WEST beautiful. 305.295.6400 keysfurniture.com WWW.KEYSINFONET.COM SATURDAY, MARCH 15, 2014 VOLUME 61, NO. 22 G 25 CENTS LAYTON’S BIG RACE CRIME FRONT Sentencing for Zecca is delayed ed the delay It’s now April or why. for man who set Zecca, a former com- up murder plot manding officer of Keynoter Staff Coast Guard Station A former U.S. Coast Islamorada, Guard commanding officer ZECCA admitted in who admitted to trying to hire federal court in November a hitman to kill a Middle that he tried to hire a hitman Keys Realtor has had his sen- to kill Marathon Realtor tencing pushed back a month. Bruce Schmitt (he was not Dennis Zecca, facing 10 injured). The hired gun turned years in federal prison, is out to be a federal informant. now scheduled for sentenc- In return for his guilty ing before U.S. District Court plea to murder for hire, the Judge Jose Martinez at 9:30 U.S. Attorney’s Office a.m. April 14 in District dropped charges of conspira- Court’s Courtroom 1 at 301 cy to possess with intent to Simonton St., Key West. distribute cocaine, attempt to He had been scheduled for possess with intent to distrib- March 25. A Wednesday court filing doesn’t say who request- See Zecca, 2A Racers in the 2014 World Famous CRIME FRONT Layton Canoe Race, organized by Mayor Norman Anderson Sex suspect and his friends, celebrate at the finish line. About a further charged dozen competitors race from the end of Cops: Hammer 1 in North South Layton Drive Carolina on Monroe near the marine lab, wanted testimony County war- and round the canals to be silenced rants charg- and return to the ing him with start/finish line. -

Celebrating FOOD! Cooking Careers Communications

Les Dames d’Escoffier invites you to... Celebrating FOOD! Cooking Careers Communications Eighth Salute to Women in Gastronomy More than 40 Speakers in 16 sessions Hands-on Cooking Classes Continental Breakfast and Lunch Included Fabulous Culinary EXPO with new products, samples, cookbooks, experts and Festival of Desserts Les Dames logo cookies from Laurie Weber’s The Swiss Bakery Dumpling and Beer Pairing Finale Much more... DATE: Saturday, March 10, 2012 TIME: 8:30 a.m. to 5:45 p.m. PLACE: The Universities at Shady Grove Rockville, Maryland 20850 COST: $99 inclusive. Free Parking. KEYNOTE SPEAKER Sara Moulton Food Editor of ABC-TV’s “Good Morning America” My Life in Food from the CIA to Network TV: Three Decades and Cookin’ A chef, author, and TV cooking show star, Sara Moulton has been the host of the TV Food Network’s “Cooking Live,” “Cooking Live Prime- time,” and “Sara’s Secrets.” In addition to her work on the Food Net- work, Sara was the Executive Chef of Gourmet Magazine for 23 years. A scholarship recipient from Les Dames’ New York Chapter, Sara grad- uated with highest honors from the Culinary Institute of America (Hyde Park) in 1977. Her TV career began in 1979, when she was hired to work behind the scenes on PBS-TV’s “Julia Child & More Company.” Her friendship with Julia led eventually to Sara’s becoming food editor at ABC- TV’s “Good Morning America.” Sara is the author of Sara Moulton Cooks at Home, Sara Moulton’s Everyday Family Dinners, and Sara’s Secrets for Weeknight Meals, which serves as the basis for “Sara’s Weeknight Meals,” a PBS-TV series that began its second season in October.