The Nature and Management of Myanmar's Alignment with China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

June Lawyer Kyi Myint and Poet Saw Wai Held a Press JANUARY Chronologyconference Regarding the Arrest Warrant2020 Against

June Lawyer Kyi Myint and Poet Saw Wai held a press JANUARY CHRONOLOGYconference regarding the arrest warrant2020 against them. Summary of the Current Situation: 647 individuals are oppressed in Burma due to political activity: 73 political prisoners are serving sentences, 141 are awaiting trial inside prison, 433 are awaiting trial outside Accessed January © Myanmar Times prison. WEBSITE | TWITTER | FACEBOOK January 2020 1 ACRONYMS ABFSU All Burma Federation of Student Unions CAT Conservation Alliance Tanawthari CNPC China National Petroleum Corporation EAO Ethnic Armed Organization GEF Global Environment Facility ICRC International Committee of the Red Cross IDP Internally Displaced Person KHRG Karen Human Rights Group KIA Kachin Independence Army KNU Karen National Union MFU Myanmar Farmers’ Union MNHRC Myanmar National Human Rights Commission MOGE Myanmar Oil and Gas Enterprise NLD National League for Democracy NNC Naga National Council PAPPL Peaceful Assembly and Peaceful Procession Law RCSS Restoration Council of Shan State RCSS/SSA Restoration Council of Shan State/Shan State Army – South SHRF Shan Human Rights Foundation TNLA Ta’ang National Liberation Army YUSU Yangon University Students’ Union January 2020 2 POLITICAL PRISONERS Note - Changes have been made to the layout and content of the Chronology. AAPP will no longer cover landmine cases and conflict between ethnic armed groups (EAGs) due to resources; detentions and torture by EAGs will still be covered. Additionally, AAPP will not cover individual protests by land rights, but will provide updates on the arrests of land rights activists. Political Prisoners ARRESTS Two RCSS members arrested in Namhsan On January 6, the military arrested two members of the Restoration Council of Shan State (RCSS) who attended a public meeting at Nar Bwe Village in Namhsan Township in southern Shan State. -

Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and Import Law Dekkhina and President U Win Myint Were and S: 25 of the District Detained

Current No. Name Sex /Age Father's Name Position Date of Arrest Section of Law Plaintiff Address Remark Condition Superintendent Myanmar Military Seizes Power Kyi Lin of and Senior NLD leaders S: 8 of the Export Special Branch, including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and Import Law Dekkhina and President U Win Myint were and S: 25 of the District detained. The NLD’s chief Natural Disaster Administrator ministers and ministers in the Management law, (S: 8 and 67), states and regions were also 1 (Daw) Aung San Suu Kyi F General Aung San State Counsellor (Chairman of NLD) 1-Feb-21 Penal Code - Superintendent House Arrest Naypyitaw detained. 505(B), S: 67 of Myint Naing Arrested State Counselor Aung the (S: 25), U Soe San Suu Kyi has been charged in Telecommunicatio Soe Shwe (S: Rangoon on March 25 under ns Law, Official 505 –b), Section 3 of the Official Secrets Secret Act S:3 Superintendent Act. Aung Myo Lwin (S: 3) Myanmar Military Seizes Power S: 25 of the and Senior NLD leaders Natural Disaster including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi Superintendent Management law, and President U Win Myint were Myint Naing, Penal Code - detained. The NLD’s chief 2 (U) Win Myint M U Tun Kyin President (Vice Chairman-1 of NLD) 1-Feb-21 Dekkhina House Arrest Naypyitaw 505(B), S: 67 of ministers and ministers in the District the states and regions were also Administrator Telecommunicatio detained. ns Law Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint were detained. -

Situation Analysis of Myanmar's Region and State Hluttaws

1 Authors This research product would not have been possible without Carl DeFaria the great interest and cooperation of Hluttaw and government representatives in Mon, Mandalay, Shan and Tanintharyi Philipp Annawitt Region and States. We would like express our heartfelt thanks to Daw Tin Ei, Speaker of the Mon State Hluttaw, U Aung Kyaw Research Team Leader Oo, Speaker of the Mandalay Region Hluttaw, U Sai Lone Seng, Aung Myo Min Speaker of the Shan State Hluttaw, and U Khin Maung Aye, Speaker of the Tanintharyi Region Hluttaw, who participated enthusiastically in this project and made themselves, their Researcher and Technical Advisor MPs and staff available for interviews, and who showed great Janelle San ownership throughout the many months of review and consultation on the findings and resulting recommendations. We also wish to thank Chief Ministers U Zaw Myint Maung, Technical Advisor Dr Aye Zan, U Linn Htut, and Dr. Le Le Maw for making Warren Cahill themselves and/or their ministers and cabinet members available for interviews, and their Secretaries of Government who facilitated travel authorizations and set up interviews Assistant Researcher with township officials. T Nang Seng Pang In particular, we would like to thank the eight constituency Research Team Members MPs interviewed for this research who took several days out of their busy schedule to organize and accompany our research Hlaing Yu Aung team on visits to often remote parts of their constituencies Min Lawe and organized the wonderful meetings with ward and village tract administrators, household heads and community Interpreters members that proved so insightful for this research and made our picture of the MP’s role in Region and State governance Dr. -

Democracy First, Federalism Next? the Constitutional Reform Process in Myanmar

ISSUE: 2019 No. 93 ISSN 2335-6677 RESEARCHERS AT ISEAS – YUSOF ISHAK INSTITUTE ANALYSE CURRENT EVENTS Singapore |8 November 2019 Democracy First, Federalism Next? The Constitutional Reform Process in Myanmar Nyi Nyi Kyaw* EXECUTIVE SUMMARY • The ruling National League for Democracy (NLD) party launched a process of constitutional amendment in February 2019, but without the support of the unelected military bloc that holds a quarter of the seats in Myanmar’s parliament, constitutional amendment remains impossible. • Whereas the NLD wants gradually to reduce the power of the military in politics, the military and its proxy Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP) seek to increase that power or at least maintain the constitutional status quo. • Ethnic political parties have called for an immediate reduction of the power of the military and demanded more devolution of powers to ethnic states. They are unhappy with the NLD’s silence concerning federalism. • The politicking over constitutional amendment has made clear that these three groups — the NLD, the military and the USDP, and ethnic parties — will each go their own way to capitalize on the rift between them for gains in the general elections due in November 2020. * Nyi Nyi Kyaw is Visiting Fellow in the Myanmar Studies Programme of ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute. 1 ISSUE: 2019 No. 93 ISSN 2335-6677 INTRODUCTION The increasingly controversial and heated topic confronting Myanmar is the 2008 Constitution of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar, under which the country’s political transition began in 2010. In the view of democrats or civilian politicians under the leadership of the ruling National League for Democracy (NLD) party and its chair State Counsellor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, the constitution gives undue power to the military. -

Recent Arrest List (Last Updated on 5 March 2021)

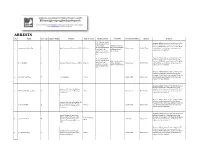

ARRESTS No. Name Sex /Age Father's Name Position Date of Arrest Section of Law Plaintiff Current Condition Address Remark S: 8 of the Export and Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD Import Law and S: 25 leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and of the Natural Superintendent Kyi President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s Disaster Management Lin of Special Branch, 1 (Daw) Aung San Suu Kyi F State Counsellor (Chairman of NLD) 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Nay Pyi Taw chief ministers and ministers in the states and law, Penal Code - Dekkhina District regions were also detained. 505(B), S: 67 of the Administrator Telecommunications Law Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD S: 25 of the Natural leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and Disaster Management Superintendent Myint President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s law, Penal Code - 2 (U) Win Myint M President (Vice Chairman-1 of NLD) 1-Feb-21 Naing, Dekkhina House Arrest Nay Pyi Taw chief ministers and ministers in the states and 505(B), S: 67 of the District Administrator regions were also detained. Telecommunications Law Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s 3 (U) Henry Van Thio M Vice President 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Nay Pyi Taw chief ministers and ministers in the states and regions were also detained. Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and Speaker of the Amyotha Hluttaw, President U Win Myint were detained. -

Total Detention, Charge and Fatality Lists

ARRESTS No. Name Sex /Age Father's Name Position Date of Arrest Section of Law Plaintiff Current Condition Address Remark S: 8 of the Export and Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD Import Law and S: 25 leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and of the Natural Superintendent Kyi President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s Disaster Management Lin of Special Branch, 1 (Daw) Aung San Suu Kyi F General Aung San State Counsellor (Chairman of NLD) 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Naypyitaw chief ministers and ministers in the states and law, Penal Code - Dekkhina District regions were also detained. 505(B), S: 67 of the Administrator Telecommunications Law Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD S: 25 of the Natural leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and Disaster Management Superintendent President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s law, Penal Code - Myint Naing, 2 (U) Win Myint M U Tun Kyin President (Vice Chairman-1 of NLD) 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Naypyitaw chief ministers and ministers in the states and 505(B), S: 67 of the Dekkhina District regions were also detained. Telecommunications Administrator Law Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s 3 (U) Henry Van Thio M Vice President 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Naypyitaw chief ministers and ministers in the states and regions were also detained. Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and Speaker of the Union Assembly, the President U Win Myint were detained. -

Burma Report BR-I 73

BURMA REPORT June 2009 jrefrmh = rSwfwrf; Issue N° 73 Free all political prisoners, free Aung San Suu Kyi, free Burma. Burma News - 24 May 2009 - "EBO" - "Burma_news" <[email protected]> Mon, 25. May 2009 Security Council - SC/9662 - 22 May 2009 SECURITY COUNCIL PRESS STATEMENT ON MYANMAR The following Security Council press statement on Myanmar was read out today by Council President Vitaly Churkin ( Russian Federation): The members of the Security Council express their concern about the political impact of recent developments relating to Daw Aung San Suu Kyi. The members of the Security Council reaffirm, in this context, their statements of 11 October 2007 and 2 May 2008 and, in this regard, reiterate the importance of the release of all political prisoners. The members of the Security Council reiterate the need for the Government of Myanmar to create the necessary conditions for a genuine dialogue with Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and all concerned parties and ethnic groups in order to achieve an inclusive national reconciliation with the support of the United Nations. The members of the Security Council affirm their commitment to the sovereignty and territorial integrity of Myanmar and, in that context, reiterate that the future of Myanmar lies in the hands of all of its people. ****************************************************************************************************** Thr Irrawaddy- COMMENTARY . Today's Newsletter for Tuesday, May 19, 2009 - [email protected] Foreign Companies in Burma Must Review Their Involvement By YENI . Tuesday, May 19, 2009 - <http://www.irrawaddy.org/print_article.php?art_id=15670> As the Burmese regime brutally increases its isolation of opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi, the US and countries of the European Union remain steadfast in applying their pressure on the junta. -

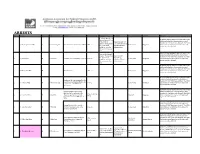

Recent Arrest List

ARRESTS No. Name Sex /Age Father's Name Position Date of Arrest Section of Law Plaintiff Current Condition Address Remark S: 8 of the Export and Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD Import Law and S: 25 leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and of the Natural Superintendent Kyi President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s General Aung Disaster Management Lin of Special Branch, 1 (Daw) Aung San Suu Kyi F State Counsellor (Chairman of NLD) 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Naypyitaw chief ministers and ministers in the states and San law, Penal Code - Dekkhina District regions were also detained. 505(B), S: 67 of the Administrator Telecommunications Law Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD S: 25 of the Natural leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and Disaster Management Superintendent President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s law, Penal Code - Myint Naing, 2 (U) Win Myint M U Tun Kyin President (Vice Chairman-1 of NLD) 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Naypyitaw chief ministers and ministers in the states and 505(B), S: 67 of the Dekkhina District regions were also detained. Telecommunications Administrator Law Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s 3 (U) Henry Van Thio M Vice President 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Naypyitaw chief ministers and ministers in the states and regions were also detained. Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and Speaker of the Union Assembly, the President U Win Myint were detained. -

Under Detention List (Last Updated on 16 July 2021)

Current No Name Sex /Age Father's Name Status Date of Arrest Section of Law Plaintiff Condition Address Region/State Remark Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Export and Import Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung Law S: 8 and Natural Superintendent Kyi San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint Disaster Linn of Special were detained. The NLD’s chief ministers Management law S: Branch, Dekkhina and ministers in the states and regions 25, Penal Code S: District Administrator were also detained. 505(b), (S: 8 and 67), Detained State Counselor Aung San Suu Telecommunications Superintendent Kyi has been charged in Rangoon on MP (Pyithu Hluttaw, Law S: 67, Official Myint Naing (S: 25), U March 25 under Section 3 of the Official Kawthmu Township, Secret Act S: 31-c, Soe Soe Shwe (S: 505 Secrets Act. Besides, she has been charged Yangon Region), Natural Disaster –b), Superintendent under the Natural Disaster Management Government (State Management Law, Aung Myo Lwin (S: 31- Law on 12-April-2021 Counsellor), NLD Anti-Corruption Law c), U Nyi Nyi (aka) U 1 Aung San Suu Kyi F General Aung San (Chairperson) 1-Feb-21 S: 55 Tun Myint Aung House Arrest Naypyitaw Naypyitaw Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung MP (Pyithu Hluttaw, Natural Disaster San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint Tamwe Township, Management law S: were detained. The NLD’s chief ministers Yangon Region), 25, Penal Code S: Superintendent and ministers in the states and regions Government 505-b, Myint Naing, were also detained. (President), NLD Telecommunications Dekkhina District 2 Win Myint M U Tun Kyin (Vice Chairman 1) 1-Feb-21 Law S: 67 Administrator House Arrest Naypyitaw Naypyitaw Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint MP (Amyotha were detained. -

Recent Arrests List

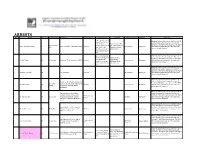

ARRESTS No. Name Sex Position Date of Arrest Section of Law Plaintiff Current Condition Address Remark Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s S: 8 of the Export and Superintendent Kyi 1 (Daw) Aung San Suu Kyi F State Counsellor (Chairman of NLD) 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Nay Pyi Taw chief ministers and ministers in the states and Import Law Lin of Special Branch regions were also detained. Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and S: 25 of the Natural President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s Superintendent Myint 2 (U) Win Myint M President (Vice Chairman-1 of NLD) 1-Feb-21 Disaster Management House Arrest Nay Pyi Taw chief ministers and ministers in the states and Naing law regions were also detained. Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s 3 (U) Henry Van Thio M Vice President 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Nay Pyi Taw chief ministers and ministers in the states and regions were also detained. Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and Speaker of the Amyotha Hluttaw, the President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s 4 (U) Mann Win Khaing Than M upper house of the Myanmar 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Nay Pyi Taw chief ministers and ministers in the states and parliament regions were also detained. -

Recent Arrests List

ARRESTS No. Name Sex Position Date of Arrest Section of Law Plaintiff Current Condition Address Remark Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s S: 8 of the Export and Superintendent Kyi 1 (Daw) Aung San Suu Kyi F State Counsellor (Chairman of NLD) 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Nay Pyi Taw chief ministers and ministers in the states and Import Law Lin of Special Branch regions were also detained. Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and S: 25 of the Natural President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s Superintendent Myint 2 (U) Win Myint M President (Vice Chairman-1 of NLD) 1-Feb-21 Disaster Management House Arrest Nay Pyi Taw chief ministers and ministers in the states and Naing law regions were also detained. Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s 3 (U) Henry Van Thio M Vice President 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Nay Pyi Taw chief ministers and ministers in the states and regions were also detained. Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and Speaker of the Amyotha Hluttaw, the President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s 4 (U) Mann Win Khaing Than M upper house of the Myanmar 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Nay Pyi Taw chief ministers and ministers in the states and parliament regions were also detained.