Unleashing the Power of Learner Agency

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Toys for the Collector

Hugo Marsh Neil Thomas Forrester Director Shuttleworth Director Director Toys for the Collector Tuesday 10th March 2020 at 10.00 PLEASE NOTE OUR NEW ADDRESS Viewing: Monday 9th March 2020 10:00 - 16:00 9:00 morning of auction Otherwise by Appointment Special Auction Services Plenty Close Off Hambridge Road NEWBURY RG14 5RL (Sat Nav tip - behind SPX Flow RG14 5TR) Dave Kemp Bob Leggett Telephone: 01635 580595 Fine Diecasts Toys, Trains & Figures Email: [email protected] www.specialauctionservices.com Dominic Foster Graham Bilbe Adrian Little Toys Trains Figures Due to the nature of the items in this auction, buyers must satisfy themselves concerning their authenticity prior to bidding and returns will not be accepted, subject to our Terms and Conditions. Additional images are available on request. Buyers Premium with SAS & SAS LIVE: 20% plus Value Added Tax making a total of 24% of the Hammer Price the-saleroom.com Premium: 25% plus Value Added Tax making a total of 30% of the Hammer Price Order of Auction 1-173 Various Die-cast Vehicles 174-300 Toys including Kits, Computer Games, Star Wars, Tinplate, Boxed Games, Subbuteo, Meccano & other Construction Toys, Robots, Books & Trade Cards 301-413 OO/ HO Model Trains 414-426 N Gauge Model Trains 427-441 More OO/ HO Model Trains 442-458 Railway Collectables 459-507 O Gauge & Larger Models 508-578 Diecast Aircraft, Large Aviation & Marine Model Kits & other Large Models Lot 221 2 www.specialauctionservices.com Various Diecast Vehicles 4. Corgi Aviation Archive, 7. Corgi Aviation Archive a boxed group of eight 1:72 scale Frontier Airliners, a boxed group of 1. -

Westmorland and Cumbria Bridge Leagues February

WBL February Newsletter 1st February 2021 Westmorland and Cumbria Bridge Leagues February Newsletter 1 WBL February Newsletter 1st February 2021 Contents Congratulations to All Winners in the January Schedule .................................................................................................. 3 A Word from your Organiser ............................................................................................................................................ 5 February Schedule ........................................................................................................................................................ 6 Teams and Pairs Leagues .......................................................................................................................................... 6 Teams Events ................................................................................................................................................................ 7 Cumbria Inter-Club Teams of Eight ........................................................................................................................... 7 A Word from the Players................................................................................................................................................... 8 From Ken Orford ........................................................................................................................................................... 8 From Jim Lawson ........................................................................................................................................................ -

Games & Puzzles Magazine (Series 1 1972

1 GAMES & PUZZLES MAGAZINE (SERIES 1 1972-1981) INDEX Preliminary Notes [DIP] Diplomacy - Don Turnbull 1-10 [DIP] Diplomacy - Alan Calhamer 37-48 G&P included many series, and where a game [DRA] Draughts - 'Will o' the Wisp' 19-30 reference relates to a series, a code in square brackets [FAN] Fantasy Games - 'Warlock' 79-81 is added. [FIG] Figures (Mathematics) - Many authors 19-71 The table below lists the series in alphabetical order [FO] Forum (Reader's letters) 1-81 [GV] Gamesview (Game reviews) 6-81 with the code shown in the left hand column. [GGW] Great Games of the World - David Patrick 6-12 Principal authors are listed together with the first and [GO] Go - Francis Roads 1-12 last issue numbers. Small breaks in publication of a [GO] Go - John Tilley 13-24 series are not noted. Not all codes are required in the [GO] Go - Stuart Dowsey 31-43 body of the index. [GO] Go, annotated game - Francis Roads 69-74 Book reviews were initially included under [MAN] Mancala - Ian Lenox-Smith 26-29 Gamesview, but under Bookview later. To distinguish [MW] Miniature Warfare - John Tunstill 1-6 book reviews from game reviews all are coded as [BV]. [OTC] On the Cards - David Parlett 29-73 [PG] Parade Ground (Wargames) - Nicky Palmer 51-81 References to the Forum series (Reader's letters - [PB] Pieces and Bits - Gyles Brandreth 1-19 Code [FO]) are restricted to letters judged to [PEN] Pentominoes - David Parlett 9-17 contribute relevant information. [PLA] Platform - Authors named in Index 64-71 Where index entries refer consecutively to a particular [PR] Playroom 43-81 game the code is given just once at the end of the [POK] Poker - Henry Fleming 6-12 issue numbers which are not separated by spaces. -

General Toys

Vectis Auctions, Vectis Auctions, Fleck Way, Thornaby, Oxford Office, Stockton-on-Tees, TS17 9JZ. Unit 5a, West End Industrial Estate, Telephone: 0044 (0)1642 750616 Witney, Oxon, OX28 1UB. Fax: 0044 (0)1642 769478 Telephone: 0044 (0)1993 709424 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.vectis.co.uk GENERAL TOY SALE Friday 9th August 2019 AUCTIONS COMMENCE AT 10.30am UNLESS OTHERWISE STATED. Room and Live On-Line Auctions at Thornaby, Stockton-on-Tees, TS17 9JZ. Viewing available on the day of the Sale from 8.00am. Bidding can be made using the following methods: Commission Bids, Postal/Fax Bids, Telephone Bidding - If you intend to bid by telephone please contact our office for further information on 0044 (0)1642 750616. Internet Bidding - you can bid live on-line with www.vectis.co.uk or www.invaluable.com. You can also leave proxy bids at www.vectis.co.uk. If you require any further information please contact our office. FORTHCOMING AUCTIONS Specialist Sale 4 Tuesday 3rd September 2019 Specialist Sale 4 Wednesday 4th September 2019 General Toy Sale 4 Thursday 5th September 2019 Specialist Matchbox Sale 4 Tuesday 24th September 2019 TV & Film Related Toy Sale 4 Thursday 26th September 2019 Model Train Sale 4 Friday 27th September 2019 Details correct at time of print but may be subject to change, please check www.vectis.co.uk for updates. Managing Director 4 Vicky Weall Cataloguers 4 David Cannings, Matthew Cotton, David Bowers & Andrew Reed Photography 4 Paul Beverley, Andrew Wilson & Simon Smith Data Input 4 Patricia McKnight & Andrea Rowntree Layout & Design 4 Andrew Wilson A subsidiary of The Hambleton Group Ltd - VAT Reg No. -

Toys for the Collector

Hugo Marsh Neil Thomas Forrester Director Shuttleworth Director Director Toys for the Collector 25th August at 10:00 GMT +1 Viewing on a rota basis by appointment only Special Auction Services Plenty Close Off Hambridge Road NEWBURY RG14 5RL Telephone: 01635 580595 Email: [email protected] www.specialauctionservices.com Bob Leggett @SpecialAuction1 Toy & Train Specialist @Specialauctionservices Due to the nature of the items in this auction, buyers must satisfy themselves concerning their authenticity prior to bidding and returns will not be accepted, subject to our Terms and Conditions. Additional images are available on request. Buyer’s Premium with SAS & SAS LIVE: 20% plus Value Added Tax making a total of 24% of the Hammer Price Buyer’s Premium with the-saleroom.com Premium: 25% plus Value Added Tax making a total of 30% of the Hammer Price 1. Motor Max 1:48 Scale WWII 7. Hobby Master 1:48 Scale WWII 13. Armour Collection 1:48 Scale Fighter Planes, a boxed group comprising Aircraft, a boxed collection from the Air WWII Aircraft, a boxed group of four, 76316 P-47 Thunderbolt (2), 76368 Zero, Power Series comprising HA7001 F2A-2 B11B567 98320 F6F5 Hellcat Kangaroos, 76369 P-40 Warhawk, 76355 F4U Corsair, Buffalo USS Saratoga (4), HA7006 limited B11B309 98167 Spitfire RAF France, 76365 P-38 Lightning, 76370 MKI Spitfire, edition F2A Buffalo USS Lexington (2), B11B293 98144 P47 Thunderbolt USAF 76336 P-51 Mustang, G-E, Boxes G-E, (8) HA7301 Grumann F3F-1 limited edition and 98006 P51 Mustang USAAF, G-E, £80-120 USS Saratoga (2), HA7101limited edition Boxes F-G, (4) Spitfire Johnnie Johnson 1945, HA7103 £80-120 2. -

Finding Aid to the Sid Sackson Collection, 1867-2003

Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play Sid Sackson Collection Finding Aid to the Sid Sackson Collection, 1867-2003 Summary Information Title: Sid Sackson collection Creator: Sid Sackson (primary) ID: 2016.sackson Date: 1867-2003 (inclusive); 1960-1995 (bulk) Extent: 36 linear feet Language: The materials in this collection are primarily in English. There are some instances of additional languages, including German, French, Dutch, Italian, and Spanish; these are denoted in the Contents List section of this finding aid. Abstract: The Sid Sackson collection is a compilation of diaries, correspondence, notes, game descriptions, and publications created or used by Sid Sackson during his lengthy career in the toy and game industry. The bulk of the materials are from between 1960 and 1995. Repository: Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play at The Strong One Manhattan Square Rochester, New York 14607 585.263.2700 [email protected] Administrative Information Conditions Governing Use: This collection is open to research use by staff of The Strong and by users of its library and archives. Intellectual property rights to the donated materials are held by the Sackson heirs or assignees. Anyone who would like to develop and publish a game using the ideas found in the papers should contact Ms. Dale Friedman (624 Birch Avenue, River Vale, New Jersey, 07675) for permission. Custodial History: The Strong received the Sid Sackson collection in three separate donations: the first (Object ID 106.604) from Dale Friedman, Sid Sackson’s daughter, in May 2006; the second (Object ID 106.1637) from the Association of Game and Puzzle Collectors (AGPC) in August 2006; and the third (Object ID 115.2647) from Phil and Dale Friedman in October 2015. -

Cratfield News

CRATFIELD NEWS May 2020 1 CONGRATULATIONS to Simone and Aaron on the birth of baby Theo 22 nd March 2020 a brother for Evie and Zach (Good news for the village in these difficult times. We hope to be able to see them out around the village before too many more weeks pass.) COVID 19 HELPLINE The Covid 19 helpline is working! Thank you to the volunteers that came forward. We now have 30 registered of which most have contributed in some way. Easter bunnies were out all over out village on Easter Sunday,,, Thank you. You made a difference. Once again for those needing to shield at home, there is help. It's only a phone call away. Thank you to everyone who silently helps their neighbour. Margaret Thompson 07906 509302 NHS The old familiar sounds of the day I miss, really eerie, didn't know it mattered at all. Then to stand on the door step and applaud our NHS workers in a small village like ours was really heartening. It was so great I phoned my daughter, Sally, who nurses in Chelsea and Westminster in London. She sounded very emotional, therefore so was I. What a lovely thing to do. “Mum I can hear a foghorn and whistles, clapping, saucepans and hoorahs!” Yes, Sally, even our small community, individually we care as much as those that live in the smoke. Even more so as we are out on a limb. So cheers to all for doing their bit and more, right across the board. A huge well done and thank you so much.. -

11/11/2019 JEWELLERY/ANTIQUES Auction Starts at 10:00Am In

11/11/2019 JEWELLERY/ANTIQUES Auction Starts at 10:00am in Saleroom (7001 - 8442) *= 20% VAT on the Hammer 25% Buyer’s Premium + VAT on the Hammer If bidding online; you will incur a further charge of 3% +VAT 7001. Five stone diamond ring, five old cut 7010. Gentlemen's yellow metal signet ring diamonds illusion set in 18ct white and yellow tested as 9ct, weight 3.1 grams, ring size S gold, gross weight 3.2 grams, ring size Q½ £20-40 £120-160 7011. Single stone diamond ear studs, round 7002. 9ct yellow gold charm bracelet, with cut diamonds mounted in a floral setting in heart clasp and safety chain, weight 36.0 grams yellow metal tested as 18ct, gross weight 2.5 £550-650 grams 7003. Gentlemen's diamond set signet ring, £100-150 round brilliant cut diamond weighing an 7012. Silver ingot pendant necklace, and a estimated 1.77cts, estimated colour and clarity, silver napkin ring, total weight 57.3 grams, VS, K-L, ring size R together with an antique gold plated locket £1800-2200 pendant and a costume ring 7004. Sapphire and diamond ring, central £10-20 cushion cut blue sapphire weighing an estimated 7013. 18ct yellow gold band ring, and an 3.00cts, four claw set in white metal tested as ornate yellow and white metal band ring set with platinum, with round brilliant cut diamonds small diamonds, stamped 18ct, gross weight 7.6 millegrain set to split shoulders, on a yellow grams metal shank stamped as 18ct, ring size J £100-150 £3000-5000 7014. -

Snakes & Ladders History

All the latest information about the Museum Of Gaming project! Issue number 2 – February 2015 In this issue... Museum Update Snakes & Ladders History Box & Board Art Archive News Totopoly (1949) Launch Party (1997) Tiddley Winks (1920-1930) Wizard's Quest (1979) Handcut Jigsaw (1935) Quintro (1920-1939) Acquisition News Fist Edition Cluedo (1949) One of the museum's early Snakes & Ladders boards, from 1910 The Last Bit About MOG Snakes & Ladders History Museum Information One of the most famous and Brahmaloka. The game is instantly recognisable board one of pure luck with no Museum Update games is the childhood real skill or strategy. This favourite Snakes & Ladders. suits its philosophical It's been three months since the Museum Of Like many games we know background, as it Gaming project was officially announced so well Snakes and Ladders emphasises the ideas of and we have already received a lot of has an interesting history. fate and destiny. positive feedback. We've have over 600 twitter followers, an active facebook group The game originated in When the game was first and a constantly expanding archive. Ancient India where it was published in England in known as “Moksha Patamu”. 1892 the cultural and We have received a couple of donations The original game was religious iconography was since the last news letter so I'd like to designed to embrace the removed and replaced with thank; Neil Forshaw for his Wizard's Quest Hindu philosophies of Karma more traditional British and Christine Robinson for her hand cut (करर) a causality based on scenes reflecting Christian jigsaw. -

Mullocks Specialist Auctioneers & Valuers

The Clive Pavilion Mullocks Specialist Auctioneers & Valuers Ludlow Racecourse Bromfield Ludlow Two Day Sale of Sporting Memorabilia SY8 2BTY Started 15 Apr 2015 11:00 BST United Kingdom Lot Description Signed 1954 Joe Davis and Fred Davis snooker exhibition programme dated 11-12/03/1954 at T.A centre Rotherham, Joes Davis (20 1 years Undefeated Snooker Champion of the World) and Fred Davis (1954 Present Snooker Champion of the World) signed by both players VG example, t/w 1955 Cavalcade of Sport pro ...[more] 2 Snooker cue tipper in bamboo and brass in good condition c/w steel tip file 2x one piece snooker cues both weighing 17oz, both without tips, but complete with the original black japanned cue cases one with a 3 Burroughes and Watts transfer label Interesting half size Bagatelle wooden table top game folding table complete with numbered gate section, and a original cue, some 4 minor wear marks to cloth and wood, however still very playable, overall size 35 x 122cm – folded 60x 35cm Billiard Tokens – 7x brass billiard tokens embossed and inscribed to the border “Ilkeston Reliable Billiard Marker” – the purpose being 5 that players would “rent” the table for a time, receiving tokens in exchange for the amount paid. 1903 Sword Fencing white metal medal with a triumphant figure to the front and ‘Dem Vaterlande Unser Streßen’ and to the rear a 6 rampant Lion over the Swiss cross, surrounded by the words ‘Eidenössisches Turnfest 1903 in Zurich’ c/w small ribbon Royal Caledonian Curling Club white metal medal with an early embossed curling -

Diecast, Tinplate & Collectors

Diecast, Tinplate & Collectors Saturday 20 November 2010 11:00 A. E. Dowse & Son Cornwall Galleries Scotland Street Sheffield S3 7DE A. E. Dowse & Son (Diecast, Tinplate & Collectors) Catalogue - Downloaded from UKAuctioneers.com Lot: 1 shuttle bus - all boxed. (10) A Revell R.M.S. Titanic plastic kit. Lot: 13 Lot: 2 A quantity of plastic interlocking building pieces, including A quantity of naval plastic kits, including Novo, Matchbox and frames, window panels, printed interior scenes, etc. Revell (boxes in poor condition). Lot: 14 Lot: 3 Enid Blyton's Mr. Pink-Whistle Interferes and Tales of Toyland, A Tri-ang clockwork powered 11" motor cruiser, 'Burnham', a (d.w.), a quantity of children's annuals and a jigsaw puzzle of plastic clockwork powered high speed cruiser - both boxed and King George VI and Queen Elizabeth in state robes. a Tri-ang all metal clockwork speedboat. Lot: 15 Lot: 4 A wooden model of a Roman interior with printed mosaic effect, Five Tri-ang and Minic plastic clockwork boats, various colours, above terracotta hypocaust and a bag of accessories, length length 15cm. 91cm. Lot: 5 Lot: 16 A Scalex battery powered plastic boat, length 34cm., two Tri- A wooden model of a Saxon hall interior, containing banqueting ang military boats, a Tri-ang clockwork rowing boat with figure table and animal enclosure, length 81cm. and a tinplate Tri-ang boat. (5) Lot: 17 Lot: 6 A nine piece toy tea set - boxed. Two Scalex electric boats, including Speedboat 415S and Derwent Cabin Cruiser 414S, together with Scalex 'Empress Luxury Motor Yacht' and a clockwork luxury motor yacht Lot: 18 'Christine' - all boxed. -

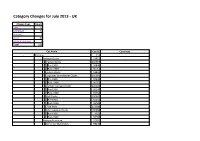

Category Tool Budy Check

Category Changes for July 2013 - UK Change Type Count New 72 Combined 70 Rename 0 Move 46 Move & Rename 0 Total 188 Cat Name Cat ID Comment - Antiques 353 - Antique Clocks 13851 - Bracket Clocks 100904 Pre-1900 66840 Post-1900 96762 Cuckoo Clocks 13850 - Longcase/ Grandfather Clocks 100905 Pre-1900 60249 Post-1900 96763 - Mantel/ Carriage Clocks 100906 Pre-1900 60248 Post-1900 96764 - Wall Clocks 100907 Pre-1900 60250 Post-1900 96765 Clock Parts 112089 - Other Antique Clocks 100908 Pre-1900 3929 Post-1900 96766 - Antique Furniture 20091 - Armoires/ Wardrobes 98436 Pre-Victorian (Pre-1837) 98437 Victorian (1837-1901) 60275 Edwardian (1901-1910) 121481 20th Century 66858 Reproduction Arms./ Wardrobes 130929 - Beds 63549 Pre-Victorian (Pre-1837) 63552 Victorian (1837-1901) 63550 Edwardian (1901-1910) 121473 20th Century 63551 Reproduction Beds 130921 - Benches/ Stools 63553 Pre-Victorian (Pre-1837) 63554 Victorian (1837-1901) 63555 Edwardian (1901-1910) 121474 20th Century 63556 Reproduction Benches/ Stools 130922 - Bookcases 63557 Pre-Victorian (Pre-1837) 63558 Victorian (1837-1901) 63559 Edwardian (1901-1910) 121475 20th Century 63560 Reproduction Bookcases 130923 - Boxes/ Chests 98430 Pre-Victorian (Pre-1837) 98431 Victorian (1837-1901) 66842 Edwardian (1901-1910) 121476 20th Century 66854 Reproduction Boxes/ Chests 130924 - Bureaux 98432 Pre-Victorian (Pre-1837) 98433 Victorian (1837-1901) 96755 Edwardian (1901-1910) 121477 20th Century 96758 Reproduction Bureaux 130925 - Cabinets 63561 Pre-Victorian (Pre-1837) 63562 Victorian (1837-1901)