Endurance and the First World War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trinity College War Memorial Mcmxiv–Mcmxviii

TRINITY COLLEGE WAR MEMORIAL MCMXIV–MCMXVIII Iuxta fidem defuncti sunt omnes isti non acceptis repromissionibus sed a longe [eas] aspicientes et salutantes et confitentes quia peregrini et hospites sunt super terram. These all died in faith, not having received the promises, but having seen them afar off, and were persuaded of them, and embraced them, and confessed that they were strangers and pilgrims on the earth. Hebrews 11: 13 Adamson, William at Trinity June 25 1909; BA 1912. Lieutenant, 16th Lancers, ‘C’ Squadron. Wounded; twice mentioned in despatches. Born Nov 23 1884 at Sunderland, Northumberland. Son of Died April 8 1918 of wounds received in action. Buried at William Adamson of Langham Tower, Sunderland. School: St Sever Cemetery, Rouen, France. UWL, FWR, CWGC Sherborne. Admitted as pensioner at Trinity June 25 1904; BA 1907; MA 1911. Captain, 6th Loyal North Lancshire Allen, Melville Richard Howell Agnew Regiment, 6th Battalion. Killed in action in Iraq, April 24 1916. Commemorated at Basra Memorial, Iraq. UWL, FWR, CWGC Born Aug 8 1891 in Barnes, London. Son of Richard William Allen. School: Harrow. Admitted as pensioner at Trinity Addy, James Carlton Oct 1 1910. Aviator’s Certificate Dec 22 1914. Lieutenant (Aeroplane Officer), Royal Flying Corps. Killed in flying Born Oct 19 1890 at Felkirk, West Riding, Yorkshire. Son of accident March 21 1917. Buried at Bedford Cemetery, Beds. James Jenkin Addy of ‘Carlton’, Holbeck Hill, Scarborough, UWL, FWR, CWGC Yorks. School: Shrewsbury. Admitted as pensioner at Trinity June 25 1910; BA 1913. Captain, Temporary Major, East Allom, Charles Cedric Gordon Yorkshire Regiment. Military Cross. -

Powys War Memorials Project Officer, Us Live with Its Long-Term Impacts

How to use this toolkit This toolkit helps local communities to record and research 4 Recording and looking after war memorials their First World War memorials. Condition of memorials Preparing a Conservation Maintenance Plan It includes information about the war, the different types of memorials Involving the community and how communities can record, research and care for their memorials. Grants It also includes case studies of five communities who have researched and produced fascinating materials about their memorials and the people they 5 Researching war memorials, the war and its stories commemorate. Finding out more about the people on the memorials The toolkit is divided into seven sections: Top tips for researching Useful websites 1 Commemorating the centenary of the First World War Places to find out more Tips from the experts 2 The First World War Regiments in Wales A truly global conflict Gathering local stories How did it all begin? A very short history of the war 6 What to do with the information Wales and the First World War A leaflet The men of Powys An interpretive panel Effects of war on communities and survivors An exhibition Why so many memorials? A First World War trail Memorials in Powys A poetry competition Poetry and musical events 3 War memorials What is a war memorial? 7 Case studies History of war memorials Brecon University of the Third Age Family History Group Types of war memorial Newtown Local History Group Symbolism of memorials Ystradgynlais Library Epitaphs The YEARGroup Materials used in war memorials L.L.A.N.I. Ltd Who is commemorated on memorials? How the names were recorded Just click on the tags below to move between the sections… 1 and were deeply affected by their experiences, sometimes for the rest Commemorating of their lives. -

General Aviation- FPA Survival

FPA 2016-17 Board of Directors Officers NORTHEAST CHAPTER External Relations: President V-P: John R. Mulvey, MD Felix R. Tormes, MD Charles R. Reinninger, MD Elkton, Maryland Pensacola, Florida Eunice, Louisiana [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Rep: James M. Timoney, DO Finance: John R. Hunt, MD Immediate Past-president (2019) Treasurer Douglas W. Johnson, MD Auburn, Maine Jacksonville, Florida [email protected] Human Factors/Safety Education: [email protected] Warren V. DeHaan, OD President-elect Rep: Mario T. Plaza-Ponte, MD Boulder, Colorado George W. Shehl, MD (2017) [email protected] Clarksburg, West Virginia Monroeville, Pennsylvania [email protected] [email protected] 2017 Nominating: Richard W. Sloan, MD, RPh Secretary SOUTHWEST CHAPTER York, Pennsylvania Mark C. Eidson, MD Rep: John D. Davis, MD [email protected] Weatherford, Texas (2019) [email protected] Hunt, Texas Publications: Mark E. Thoman, MD [email protected] Western Chapter VP Treasurer John R. Hunt, MD WESTERN CHAPTER Right Front Seaters: Anderson, South Carolina V-P: Mark E. Thoman, MD Carrie Reinninger [email protected] Port Orchard, Washington Eunice, Louisiana BOD Vice-Presidents and [email protected] [email protected] Representatives DIXIE CHAPTER Rep: J. Randall “Randy” Samaritan: V-P: Nitin D. Desai, MD Edwards, MD John E. Freitas, MD (2016) Las Vegas, Nevada Great Lakes Chapter VP Fayetteville, North Carolina [email protected] [email protected] Tours: Bernard A. Heckman, MD COMMITTEE CHAIRS Silver Spring, Maryland Rep: Trevor L. Goldberg, MD Awards: [email protected] (2018) Roger B. Hallgren, MD Burnsville, North Carolina Belle Plaine, Minnesota [email protected] [email protected] Rep: W. -

August 13, 2011 Olin Park | Madison, WI 25Years of Great Taste

August 13, 2011 Olin Park | Madison, WI 25years of Great Taste MEMORIES FOR SALE! Be sure to pick up your copy of the limited edition full-color book, The Great Taste of the Midwest: Celebrating 25 Years, while you’re here today. You’ll love reliving each and every year of the festi- val in pictures, stories, stats, and more. Books are available TODAY at the festival souve- nir sales tent, and near the front gate. They will be available online, sometime after the festival, at the Madison Homebrewers and Tasters Guild website, http://mhtg.org. WelcOMe frOM the PresIdent elcome to the Great taste of the midwest! this year we are celebrating our 25th year, making this the second longest running beer festival in the country! in celebration of our silver anniversary, we are releasing the Great taste of the midwest: celebrating 25 Years, a book that chronicles the creation of the festival in 1987W and how it has changed since. the book is available for $25 at the merchandise tent, and will also be available by the front gate both before and after the event. in the forward to the book, Bill rogers, our festival chairman, talks about the parallel growth of the craft beer industry and our festival, which has allowed us to grow to hosting 124 breweries this year, an awesome statistic in that they all come from the midwest. we are also coming close to maxing out the capacity of the real ale tent with around 70 cask-conditioned beers! someone recently asked me if i felt that the event comes off by the seat of our pants, because sometimes during our planning meetings it feels that way. -

British Identity, the Masculine Ideal, and the Romanticization of the Royal Flying Corps Image

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 4-2019 A Return to Camelot?: British Identity, The Masculine Ideal, and the Romanticization of the Royal Flying Corps Image Abby S. Whitlock College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Whitlock, Abby S., "A Return to Camelot?: British Identity, The Masculine Ideal, and the Romanticization of the Royal Flying Corps Image" (2019). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 1276. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/1276 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Return to Camelot?: British Identity, The Masculine Ideal, and the Romanticization of the Royal Flying Corps Image Abby Stapleton Whitlock Undergraduate Honors Thesis College of William and Mary Lyon G. Tyler Department of History 24 April 2019 Whitlock !2 Whitlock !3 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ……………………………………………………………….. 4 Introduction …………………………………….………………………………… 5 Chapter I: British Aviation and the Future of War: The Emergence of the Royal Flying Corps …………………………………….……………………………….. 13 Wartime Developments: Organization, Training, and Duties Uniting the Air Services: Wartime Exigencies and the Formation of the Royal Air Force Chapter II: The Cultural Image of the Royal Flying Corps .……….………… 25 Early Roots of the RFC Image: Public Imagination and Pre-War Attraction to Aviation Marketing the “Cult of the Air Fighter”: The Dissemination of the RFC Image in Government Sponsored Media Why the Fighter Pilot? Media Perceptions and Portrayals of the Fighter Ace Chapter III: Shaping the Ideal: The Early Years of Aviation Psychology .…. -

Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell

Copyrights sought (Albert) Basil (Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell) Filson Young (Alexander) Forbes Hendry (Alexander) Frederick Whyte (Alfred Hubert) Roy Fedden (Alfred) Alistair Cooke (Alfred) Guy Garrod (Alfred) James Hawkey (Archibald) Berkeley Milne (Archibald) David Stirling (Archibald) Havergal Downes-Shaw (Arthur) Berriedale Keith (Arthur) Beverley Baxter (Arthur) Cecil Tyrrell Beck (Arthur) Clive Morrison-Bell (Arthur) Hugh (Elsdale) Molson (Arthur) Mervyn Stockwood (Arthur) Paul Boissier, Harrow Heraldry Committee & Harrow School (Arthur) Trevor Dawson (Arwyn) Lynn Ungoed-Thomas (Basil Arthur) John Peto (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin & New Statesman (Borlasse Elward) Wyndham Childs (Cecil Frederick) Nevil Macready (Cecil George) Graham Hayman (Charles Edward) Howard Vincent (Charles Henry) Collins Baker (Charles) Alexander Harris (Charles) Cyril Clarke (Charles) Edgar Wood (Charles) Edward Troup (Charles) Frederick (Howard) Gough (Charles) Michael Duff (Charles) Philip Fothergill (Charles) Philip Fothergill, Liberal National Organisation, N-E Warwickshire Liberal Association & Rt Hon Charles Albert McCurdy (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett & World Review of Reviews (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Colin) Mark Patrick (Crwfurd) Wilfrid Griffin Eady (Cyril) Berkeley Ormerod (Cyril) Desmond Keeling (Cyril) George Toogood (Cyril) Kenneth Bird (David) Euan Wallace (Davies) Evan Bedford (Denis Duncan) -

The Mercurian Volume 3, No

The Mercurian A Theatrical Translation Review Volume 3, Number 4 Editor: Adam Versényi ISSN 2160-3316 The Mercurian is named for Mercury who, if he had known it, was/is the patron god of theatrical translators, those intrepid souls possessed of eloquence, feats of skill, messengers not between the gods but between cultures, traders in images, nimble and dexterous linguistic thieves. Like the metal mercury, theatrical translators are capable of absorbing other metals, forming amalgams. As in ancient chemistry, the mercurian is one of the five elementary “principles” of which all material substances are compounded, otherwise known as “spirit”. The theatrical translator is sprightly, lively, potentially volatile, sometimes inconstant, witty, an ideal guide or conductor on the road. The Mercurian publishes translations of plays and performance pieces from any language into English. The Mercurian also welcomes theoretical pieces about theatrical translation, rants, manifestos, and position papers pertaining to translation for the theatre, as well as production histories of theatrical translations. Submissions should be sent to: Adam Versényi at [email protected] or by snail mail: Adam Versényi, Department of Dramatic Art, CB# 3230, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3230. For translations of plays or performance pieces, unless the material is in the public domain, please send proof of permission to translate from the playwright or original creator of the piece. Since one of the primary objects of The Mercurian is to move translated pieces into production, no translations of plays or performance pieces will be published unless the translator can certify that he/she has had an opportunity to hear the translation performed in either a reading or another production-oriented venue. -

The War Poet - Francis Ledwidge

Volume XXXIX, No. 7 • September (Fómhair), 2013 The War Poet - Francis Ledwidge .........................................................................................................On my wall sits a batik by my old Frank fell in love with Ellie Vaughey, one looked at familiar things seen thus for friend, Donegal artist Fintan Gogarty, with the sister of his friend, Paddy. Of her, he the first time. I wrote to him greeting him a mountain and lake scene. Inset in the would write, as a true poet, which indeed he was . .” piece is a poem, “Ardan Mor.” The poem “I wait the calling of the orchard maid, Frank was also involved in the arts in reads, Only I feel that she will come in blue, both Dublin and Slane. He was involved As I was climbing Ardan Mór With yellow on her hair, and two curls in many aspects of the local community From the shore of Sheelin lake, strayed and was a natural leader and innovator. He I met the herons coming down Out of her comb's loose stocks, and I founded the Slane Drama Group in which Before the water’s wake. shall steal he was actor and producer. And they were talking in their flight Behind and lay my hands upon her eyes.” In 1913, Ledwidge would form a branch Of dreamy ways the herons go At the same time, the poetry muse of the Irish Volunteers, or Óglaigh na When all the hills are withered up encompassed the being of young Frank. hÉireann. The Volunteers included members Nor any waters flow. He would write poems constantly, and in of the Gaelic League, Ancient Order of The words are by Francis Ledwidge, an 1912, mailed a number of them to Lord Hibernians and Sinn Féin, as well as mem- Irish poet. -

Warriors Walk Heritage Trail Wellington City Council

crematoriumchapel RANCE COLUMBARIUM WALL ROSEHAUGH AVENUE SE AFORTH TERRACE Wellington City Council Introduction Karori Cemetery Servicemen’s Section Karori Serviceman’s Cemetery was established in 1916 by the Wellington City Council, the fi rst and largest such cemetery to be established in New Zealand. Other local councils followed suit, setting aside specifi c areas so that each of the dead would be commemorated individually, the memorial would be permanent and uniform, and there would be no distinction made on the basis of military or civil rank, race or creed. Unlike other countries, interment is not restricted to those who died on active service but is open to all war veterans. First contingent leaving Karori for the South African War in 1899. (ATL F-0915-1/4-MNZ) 1 wellington’s warriors walk heritage trail Wellington City Council The Impact of Wars on New Zealand New Zealanders Killed in Action The fi rst major external confl ict in which New Zealand was South African War 1899–1902 230 involved was the South African War, when New Zealand forces World War I 1914–1918 18,166 fought alongside British troops in South Africa between 1899 and 1902. World War II 1939–1945 11,625 In the fi rst decades of the 20th century, the majority of New Zealanders Died in Operational New Zealand’s population of about one million was of British descent. They identifi ed themselves as Britons and spoke of Services Britain as the ‘Motherland’ or ‘Home’. Korean War 1950–1953 43 New Zealand sent an expeditionary force to the aid of the Malaya/Malaysia 1948–1966 20 ‘Mother Country’ at the outbreak of war on 4 August 1914. -

Arthur Tryweryn Apsimon

111: Arthur Tryweryn Apsimon Basic Information [as recorded on local memorial or by CWGC] Name as recorded on local memorial or by CWGC: Arthur Tryweryn Apsimon Rank: Lieutenant Battalion / Regiment: 14th Bn. Royal Welsh Fusiliers Service Number: Date of Death: 4 August 1917 Age at Death: 34 Buried / Commemorated at: Bard Cottage Cemetery, Ypres (Ieper), Arrondissement Ieper, West Flanders Belgium Additional information given by CWGC: The son of Thomas and Anna Elizabeth Apsimon, of 107, Liscard Rd., Wallasey. Native of Liverpool. Arthur Tryweryn Apsimon was born in April 1883 in the Toxteth Park district of Liverpool, the third of four sons of Thomas and Anne Elizabeth Apsimon. It is not known where or when Thomas and Anne married but, at the time of the 1881 census, two years before Arthur was born, they were living in Toxteth Park with their two young sons although Thomas was not in the household on census night: 1881 census (extract) – 14, Amberley Street, Toxteth Park, Liverpool Anne E. Apsimon 27 milling engineer’s wife born America, New York Joseph H. 1 year 10 months born Liverpool Thomas T. 5 months born Liverpool Bertha Upton 19 servant, nurse born Liverpool Catherine James 18 general servant born Cardiganshire Amberley Street exists now only as the entrance to the car park of the Merseyside Caribbean Council Community Centre to the west of the junction of Upper Parliament Street and Mulgrave Street. The family had moved to Birkdale, near Southport, by 1885 when their last child, Estyn Douglas Apsimon, was born but at the time of the 1891 census they were living near Sowerby Bridge in the Upper Calder valley in West Yorkshire. -

Blackadder Goes Forth Audition Pack

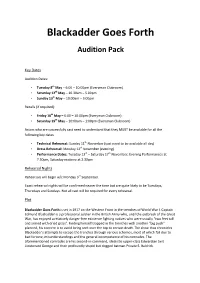

Blackadder Goes Forth Audition Pack Key Dates Audition Dates: • Tuesday 8 th May – 6:00 – 10:00pm (Everyman Clubroom) • Saturday 12 th May – 10.30am – 5.00pm • Sunday 13 th May – 10:00am – 3.00pm Recalls (if required): • Friday 18 th May – 6:00 – 10:00pm (Everyman Clubroom) • Saturday 19 th May – 10:00am – 1:00pm (Everyman Clubroom) Actors who are successfully cast need to understand that they MUST be available for all the following key dates • Technical Rehearsal: Sunday 11 th November (cast need to be available all day) • Dress Rehearsal: Monday 12 th November (evening) • Performance Dates: Tuesday 13 th – Saturday 17 th November; Evening Performances at 7.30pm, Saturday matinee at 2.30pm Rehearsal Nights Rehearsals will begin w/c Monday 3 rd September. Exact rehearsal nights will be confirmed nearer the time but are quite likely to be Tuesdays, Thursdays and Sundays. Not all cast will be required for every rehearsal. Plot Blackadder Goes Forth is set in 1917 on the Western Front in the trenches of World War I. Captain Edmund Blackadder is a professional soldier in the British Army who, until the outbreak of the Great War, has enjoyed a relatively danger-free existence fighting natives who were usually "two feet tall and armed with dried grass". Finding himself trapped in the trenches with another "big push" planned, his concern is to avoid being sent over the top to certain death. The show thus chronicles Blackadder's attempts to escape the trenches through various schemes, most of which fail due to bad fortune, misunderstandings and the general incompetence of his comrades. -

1 Battle Weariness and the 2Nd New Zealand Division During the Italian Campaign, 1943-45

‘As a matter of fact I’ve just about had enough’;1 Battle weariness and the 2nd New Zealand Division during the Italian Campaign, 1943-45. A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History at Massey University New Zealand. Ian Clive Appleton 2015 1 Unknown private, 24 Battalion, 2nd New Zealand Division. Censorship summaries, DA 508/2 - DA 508/3, (ANZ), Censorship Report No 6/45, 4 Feb to 10 Feb 45, part 2, p.1. Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. Abstract By the time that the 2nd New Zealand Division reached Italy in late 1943, many of the soldiers within it had been overseas since early 1941. Most had fought across North Africa during 1942/43 – some had even seen combat earlier, in Greece and Crete in 1941. The strain of combat was beginning to show, a fact recognised by the division’s commanding officer, Lieutenant-General Bernard Freyberg. Freyberg used the term ‘battle weary’ to describe both the division and the men within it on a number of occasions throughout 1944, suggesting at one stage the New Zealanders be withdrawn from operations completely. This study examines key factors that drove battle weariness within the division: issues around manpower, the operational difficulties faced by the division in Italy, the skill and tenacity of their German opponent, and the realities of modern combat.