North Devon and Newfoundland: a Four Hundred Year Story

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dartmouth Conservation Area Appraisal

Dartmouth Conservation Area Appraisal Conservation Areas are usually located in the older parts of our towns and villages. They are places whose surviving historic, architectural and locally distinctive features make them special. Conservation area designation highlights the need to preserve and reinforce these qualities. The policies followed by the District Council when assessing proposals affecting conservation areas are set out in the South Hams Local Development Framework, while the Supplementary Planning Document ‘New Work in Conservation Areas’ explains how to achieve compliance with them. This is essential because the Council has a statutory duty to approve proposals only if they “preserve or enhance the character or appearance” of the conservation area. The purpose of this appraisal is to set out what makes the Dartmouth Conservation Area special, what needs to be conserved and what needs to be improved. Four extensions to the conservation area are proposed and described The contents are based on an earlier draft Conservation Area Appraisal prepared for the District Council in 1999. January 2013 Dartmouth Dartmouth Conservation Area: Summary of Special Interest The position of Dartmouth at the mouth of the river Dart is of such strategic military and commercial importance, and its sheltered natural harbour so perfect, that it developed into an important town from the Middle Ages on, despite being inaccessible to wheeled transport until the 19th century. The advent of Victoria Road, Newcomen Road and later, College Way may have changed all that, but much of the character of the ancient, pedestrian town has survived. While it addresses the water, Dartmouth is a town of intimate spaces, unexpected flights of steps or pathways and steep, narrow streets with architectural jewels like St Saviours Church or the houses of the Butterwalk set amongst them. -

88C Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

88C bus time schedule & line map 88C Newton Abbot - South Devon College View In Website Mode The 88C bus line (Newton Abbot - South Devon College) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Newton Abbot: 5:25 PM (2) Paignton: 7:15 AM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 88C bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 88C bus arriving. Direction: Newton Abbot 88C bus Time Schedule 61 stops Newton Abbot Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 5:25 PM South Devon College, Paignton Tuesday 5:25 PM Long Road, Paignton Wednesday 5:25 PM Waddeton Industrial Estate, Paignton Thursday 5:25 PM Brixham Road, Paignton Friday 5:25 PM Bookers, Paignton Saturday Not Operational Tweenaways Cross, Collaton St Mary Parkers Arms, Collaton St Mary Primary School, Collaton St Mary 88C bus Info Saxon Meadow, Paignton Direction: Newton Abbot Stops: 61 Ardene, Collaton St Mary Trip Duration: 95 min Line Summary: South Devon College, Paignton, Long Berkley Hotel, Blagdon Road, Paignton, Waddeton Industrial Estate, Paignton, Bookers, Paignton, Tweenaways Cross, Collaton St Mary, Parkers Arms, Collaton St Mary, Devon Hills Holiday Park, Blagdon Primary School, Collaton St Mary, Ardene, Collaton St Mary, Berkley Hotel, Blagdon, Devon Hills Holiday Town Parks Fishing, Blagdon Park, Blagdon, Town Parks Fishing, Blagdon, Half Way Orchard, Blagdon, Longcombe Cross, Half Way Orchard, Blagdon Longcombe, True Street, Bridgetown, Highlands, Bridgetown, Cross Park, Bridgetown, Seymour Place, Longcombe Cross, Longcombe -

Davince Tools Generated PDF File

" ~~, W"ted Immediately a CARS AND PICK·UP TRUCKS r 1953's, 1954's, 195,5'5, 1956's ARE WANTED. THE DAILY NEWS Nova Motors Ltd I ~~ Vol. 66. No. 125 ST, 'JOHN'5, NEWFOUNDLAND MONDAY, JUNE 8, 1959 (Price: 7 Cents) Charles Hutton & Sons ~::~--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------~------------------------------!---------------,------.. ,----~~~ nada Will 'Launch ;'Ir, i . Satellite 1961 ,ill" ' . A ~ In . ., . I '. (OWSS Irockcts, 8:1d the radar station- lite will orbit over the pol~. It IMr, Dlefenbeker said the rocket I .'· 'jI' I Star! Wrl1rr 11'111 do Important research In the is und~r~tood it will be partieul. Is or a new C;anadian design, ! · 1": . ~tnT. Sa<k. 'CI"; upper atm~sphere 01 the nor.th. arly desisned for research in 1 Dr, Curie said scientists havr' '.\'.11'1' : " . ,\L~prr~\c \'ith the One goa~ Will ,be to. do s0!1'ethmg that part of the atmosphere con· pressed for several years for i 'I' \!; . ~;~" \ ' : ,! ~~ l ,~teUiIl'. to. oboll.1 d~sl'upllons m radiO com· cerned with radio commllnicm morc usc o[ the Churchill base in II .. 1 ..• I~t ~nd ,,'Ill :1: n ~untca\lons, call sed when pay' lion. taunching research rockets. The :,(; i I ::" oler lilc pull's .. tides of the sun enter the carth s Satellitcs ~o far hal'e bcen at llasc is wcll·situated [or studying I I . .. ':" Ih'I\'nl>;lkrr at mop h c r e, a phenomenon an angle 01 40 or ;0 degrccs to the auroral zonc, "ct only a fcw I 1 I ,!.. :;,i. '1 ": ' . ·1:;~Jr.I'cn:,'nlU"'" ~:lIU:·· known a~ thi' e northern I ghts. -

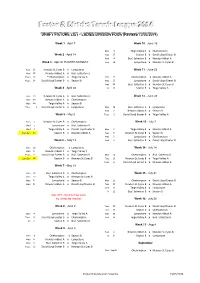

Fix Div 1 with David Lloyd D.Xlsx

DRAFT FIXTURE LIST - LADIES DIVISION FOUR (Revised 13/03/2014) Week 1 - April 7 Week 10 - June 16 Mon 16 Teign Valley A v Okehampton Week 2 - April 14 Tues 17 Seaton B v David Lloyd Exeter B Wed 18 Bud. Salterton B v Newton Abbot A Week 3 - April 21 EASTER MONDAY Wed 18 Lympstone v Newton St.Cyres B Tues 22 Newton St.Cyres B v Lympstone Week 11 - June 23 Wed 23 Newton Abbot A v Bud. Salterton B Thurs 24 **Okehampton v Teign Valley A Mon 23 Okehampton v Newton Abbot A Thurs 24 David Lloyd Exeter B v Seaton B Wed 25 Lympstone v David Lloyd Exeter B Wed 25 Bud. Salterton B v Newton St.Cyres B Week 4 - April 28 Fri 27 Seaton B v Teign Valley A Tues 29 Newton St.Cyres B v Bud. Salterton B Week 12 - June 30 Wed 30 Newton Abbot A v Okehampton Wed 30 Teign Valley A v Seaton B Thurs 1 David Lloyd Exeter B v Lympstone Mon 30 Bud. Salterton B v Lympstone Wed 2 Newton Abbot A v Seaton B Week 5 - May 5 Thurs 3 David Lloyd Exeter B v Teign Valley A Tues 6 Newton St.Cyres B v Okehampton Week 13 - July 7 Wed 7 Lympstone v Bud. Salterton B Wed 7 Teign Valley A v David Lloyd Exeter B Mon 7 Teign Valley A v Newton Abbot A 1 pm Sun 11 Seaton B v Newton Abbot A Tues 8 Newton St.Cyres B v Seaton B Wed 9 Lympstone v Okehampton Week 6 - May 12 Wed 9 Bud. -

The Extent of Indigenous-Norse Contact and Trade Prior to Columbus Donald E

Oglethorpe Journal of Undergraduate Research Volume 6 | Issue 1 Article 3 August 2016 The Extent of Indigenous-Norse Contact and Trade Prior to Columbus Donald E. Warden Oglethorpe University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/ojur Part of the Canadian History Commons, European History Commons, Indigenous Studies Commons, Medieval History Commons, Medieval Studies Commons, and the Scandinavian Studies Commons Recommended Citation Warden, Donald E. (2016) "The Extent of Indigenous-Norse Contact and Trade Prior to Columbus," Oglethorpe Journal of Undergraduate Research: Vol. 6 : Iss. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/ojur/vol6/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Oglethorpe Journal of Undergraduate Research by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Extent of Indigenous-Norse Contact and Trade Prior to Columbus Cover Page Footnote I would like to thank my honors thesis committee: Dr. Michael Rulison, Dr. Kathleen Peters, and Dr. Nicholas Maher. I would also like to thank my friends and family who have supported me during my time at Oglethorpe. Moreover, I would like to thank my academic advisor, Dr. Karen Schmeichel, and the Director of the Honors Program, Dr. Sarah Terry. I could not have done any of this without you all. This article is available in Oglethorpe Journal of Undergraduate Research: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/ojur/vol6/iss1/3 Warden: Indigenous-Norse Contact and Trade Part I: Piecing Together the Puzzle Recent discoveries utilizing satellite technology from Sarah Parcak; archaeological sites from the 1960s, ancient, fantastical Sagas, and centuries of scholars thereafter each paint a picture of Norse-Indigenous contact and relations in North America prior to the Columbian Exchange. -

Teignmouth Economic and Data Profile Indices of Deprivation

Teignmouth economic and data profile Included in this profile are recently published datasets, where these are provided for Teignmouth, or for Teignbridge where this is relevant and recent. Additional data may be available from [email protected] upon request to support business cases, where the objective of the case, or bid and bid selection criteria are provided. Indices of deprivation These are reviewed once every four years. Data is provided at the Lower Level Super Output Area (LSOA) which are neighbourhoods of around 1,500-2,000 people. There are 32,844 LSOAs in England and each one is ranked against each other to provide a relative overall position nationally for each neighbourhood. A score of 100% is the least deprived in England and a score of 0% is the most deprived. The index is provided as an overall composite measure of deprivation but is made up of a number of sub-domains, for example income, which are also published alongside the overall index. Often if bidding for national funding pots where deprivation is a factor considered as part of the scoring criteria, the criteria will ask whether the proposed project is in an LSOA that is in the worst 10%/20%/25% in England. Sometimes it can also be helpful even if the project is not within a most deprived LSOA, but is within a mile, or so of them and serves people who live within the most deprived areas to articulate this in the bid. Separately the income and skills domains from the indices of deprivation showing better performing areas can be useful as a proxy of high, or improving levels of income, or skills to articulate to businesses wishing to invest in Teignmouth of the potential market or workforce available. -

Unravelling Devon Involvement in Slave-Ownership Lucy

Unravelling Devon involvement in Slave-Ownership Lucy MacKeith ‘The early history of the United States of America owes more to Devon than to any other English county.’ Charles Owen (ed.), The Devon-American Story (1980) My task this afternoon is to unravel Devon’s involvement in slave-ownership. I have found the task overwhelming because of constantly finding new information – there are leads to follow down little branches of family trees, there are Devon’s country houses, a wealth of documents, and – of course – the internet. So this is a VERY brief introduction to unravelling Devon’s involvement with slave- ownership – much has been left out. Let’s start with Elias Ball. His story is in Slaves in the Family, written by descendant Edward Ball and published in 1998. Elias Ball by Jeremiah Theus (1716-1774). ‘Elias Ball, ...was born in 1676 in a tiny hamlet in western England called Stokeinteignhead. He inherited a plantation in Carolina at the end of the seventeenth century ...His life shows how one family entered the slave business in the birth hours of America. It is a tale composed equally of chance, choice and blood.’ The book has many Devon links – an enslaved woman called Jenny Buller reminds us of Redvers Buller’s family, a hill in one of the Ball plantations called ‘Hallidon Hill’ reminds us of Haldon Hill just outside Exeter; two family members return to England, one after the American War of Independence. This was Colonel Wambaw Elias Ball who had been involved in trading in enslaved Africans in Carolina. He was paid £12,700 sterling from the British Treasury and a lifetime pension in compensation for the slaves he had lost in the war of independence. -

West of Exeter Route Resilience Study Summer 2014

West of Exeter Route Resilience Study Summer 2014 Photo: Colin J Marsden Contents Summer 2014 Network Rail – West of Exeter Route Resilience Study 02 1. Executive summary 03 2. Introduction 06 3. Remit 07 4. Background 09 5. Threats 11 6. Options 15 7. Financial and economic appraisal 29 8. Summary 34 9. Next steps 37 Appendices A. Historical 39 B. Measures to strengthen the existing railway 42 1. Executive summary Summer 2014 Network Rail – West of Exeter Route Resilience Study 03 a. The challenge the future. A successful option must also off er value for money. The following options have been identifi ed: Diffi cult terrain inland between Exeter and Newton Abbot led Isambard Kingdom Brunel to adopt a coastal route for the South • Option 1 - The base case of continuing the current maintenance Devon Railway. The legacy is an iconic stretch of railway dependent regime on the existing route. upon a succession of vulnerable engineering structures located in Option 2 - Further strengthening the existing railway. An early an extremely challenging environment. • estimated cost of between £398 million and £659 million would Since opening in 1846 the seawall has often been damaged by be spread over four Control Periods with a series of trigger and marine erosion and overtopping, the coastal track fl ooded, and the hold points to refl ect funding availability, spend profi le and line obstructed by cliff collapses. Without an alternative route, achieved level of resilience. damage to the railway results in suspension of passenger and Option 3 (Alternative Route A)- The former London & South freight train services to the South West peninsula. -

Second Anniversary

What is a Critic? The Evil of Violence Conversation Cerith Mathias looks at the Gary Raymond explores the nature of Steph Power talks to Wales Window of Birmingham, arts criticism in a letter addressed to WNO’s David Alabama the future Pountney Wales Arts Review ANNIVERSARY SPECIAL Wales Arts Review - Anniversary Special 1 Wales Arts Contents Review Senior Editor Gary Raymond Managing Editor Phil Morris Design Editor Dean Lewis Fiction Editor John Lavin Music Editor Steph Power Non Fiction Up Front 3 A Letter Addressed to the Future: Editor What is a Critic? Ben Glover Gary Raymond Features 5 Against the Evil of Violence – The Wales Window of Alabama Cerith Mathias PDF Designer 8 An Interview with David Pountney, Artistic Ben Glover Director of WNO Steph Power 15 Epiphanies – On Joyce’s ‘The Dead’ John Lavin 20 Wales on Film: Zulu (1964) Phil Morris 22 Miles Beyond Glyndwr: What Does the Future Hold for Welsh Language Music? Elin Williams 24 Occupy Gezi: The Cultural Impact James Lloyd 28 The Thrill of it All: Glam! David Bowie Is… and the Curious Case of Adrian Street Craig Austin 31 Wales’ Past, Present and Future: A Land of Possibilities? Rhian E Jones 34 Jimmy Carter: Truth and Dare Ben Glover 36 Women and Parliament Jenny Willott MP 38 Cambriol Jon Gower 41 Postcards From The Basque Country: Imagined Communities Dylan Moore 43 Tennessee Williams: There’s No Success Like Failure Georgina Deverell 47 To the Detriment of Us All: The Untouched Legacy of Arthur Koestler and George Orwell Gary Raymond Wales Arts Review - Anniversary Special 2 by Gary Raymond In the final episode of Julian Barnes’ 1989 book, The History read to know we are not alone, as CS Lewis famously said, of the World in 10 ½ Chapters, titled ‘The Dream’, the then we write for similar reasons, and we write criticism protagonist finds himself in a Heaven, his every desire because it is the next step on from discursiveness; it is the catered for by a dedicated celestial personal assistant. -

The Evolving Relationship Between Food and Tourism: a Case Study Of

1 THE EVOLVING RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN FOOD AND TOURISM: A CASE STUDY OF DEVON THROUGH THE TWENTIETH CENTURY Submitted by: Paul Edward Cleave, to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Management Studies. November 2011 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without prior acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Signature............................................. 2 Acknowledgements I would like to thank everyone who contributed so generously and patiently of their time and expertise in the completion of this thesis, and especially to my supervisor, Professor Gareth Shaw for his guidance and inspiration. Their unfailing support and encouragement in my endeavours is greatly appreciated. Paul Cleave 3 Abstract The aim of this thesis is to examine the evolving relationship between food and tourism through the twentieth century. Devon, a county in the South West of England, and a popular tourist destination is used as the geographical focus of the case study. Previous studies have tended to focus on particular locations at a fixed point in time, not over the timescale of a century. The research presents a social and economic history of food in the context of tourism. It incorporates many food related interests reflecting the topical and evolving, embracing leisure, pleasure and social history, Burnett (2004). -

Colonial Failure in the Anglo-North Atlantic World, 1570-1640 (2015)

FINDLEY JR, JAMES WALTER, Ph.D. “Went to Build Castles in the Aire:” Colonial Failure in the Anglo-North Atlantic World, 1570-1640 (2015). Directed by Dr. Phyllis Whitman Hunter. 266pp. This study examines the early phases of Anglo-North American colonization from 1570 to 1640 by employing the lenses of imagination and failure. I argue that English colonial projectors envisioned a North America that existed primarily in their minds – a place filled with marketable and profitable commodities waiting to be extracted. I historicize the imagined profitability of commodities like fish and sassafras, and use the extreme example of the unicorn to highlight and contextualize the unlimited potential that America held in the minds of early-modern projectors. My research on colonial failure encompasses the failure of not just physical colonies, but also the failure to pursue profitable commodities, and the failure to develop successful theories of colonization. After roughly seventy years of experience in America, Anglo projectors reevaluated their modus operandi by studying and drawing lessons from past colonial failure. Projectors learned slowly and marginally, and in some cases, did not seem to learn anything at all. However, the lack of learning the right lessons did not diminish the importance of this early phase of colonization. By exploring the variety, impracticability, and failure of plans for early settlement, this study investigates the persistent search for usefulness of America by Anglo colonial projectors in the face of high rate of -

By Culturenet Cymru

www.casgliadywerincymru.co.uk www.peoplescollectionwales.co.uk Learning Activity Key Stage 3 This resource provides learning activities for your students using People's Collection Wales. It is one of a series of nine relating to Patagonia for KS3. Establishment of the Welsh Settlement in Patagonia The Voyage of the Mimosa, 1865 The Native Patagonians and the Welsh Settlers Early days in Patagonia 'Crossing the Patagonian plains': from the Camwy Valley to Cwm Hyfryd Dark times – Floods and Emigration Early Schools in the Welsh Settlement - Patagonia History of the Welsh Language in Patagonia Chapels and Churches in Patagonia The establishment of the Welsh Settlement in Patagonia By Culturenet Cymru Introduction The aim of the supporters of the Welsh Settlement is not to promote emigration, but to regulate it. The Reverend Michael D. Jones, c.1860 Tasks and learning objectives 1 Life in nineteenth century Wales 2 Landowners in Wales 3 Religious and cultural ideals 4 Camwy Valley 5 Society Today Download the Collection of images and worksheets for this activity from People’s Collection Wales The Establishment of the Welsh Settlement in Patagonia The establishment of the Welsh Settlement in Patagonia 'The aim of the supporters of the Welsh Settlement is not to promote emigration, but to regulate it.' The Reverend Michael D. Jones, c.1860 The idea of establishing a specifically 'Welsh' community in another part of the world emerged long before the mid-nineteenth century. As early as the 1610s, William Vaughan (1577-1641) sought to establish a Welsh community called 'Cambriol' in Newfoundland and, over the following two centuries, several individuals had similar aspirations.