Chapter One 1* Baocgi«)Und Information 1.1 the Problem

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Final Report Manipur State

Directorate General NDRF & Civil Defence (Fire) Ministry of Home Affairs East Block 7, Level 7, NEW DELHI, 110066, Fire Hazard and Risk Analysis in the Country for Revamping the Fire Services in the Country Final Report – State Wise Risk Assessment, Infrastructure and Institutional Assessment of Phase IV States (Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland, Orissa, Sikkim, Tripura, and West Bengal) November 2012 Submitted by RMSI A-8, Sector 16 Noida 201301, INDIA Tel: +91-120-251-1102, 2101 Fax: +91-120-251-1109, 0963 www.rmsi.com Contact: Sushil Gupta General Manager, Risk Modeling and Insurance Email:[email protected] Fire-Risk and Hazard Analysis in the Country Table of Contents Table of Contents .................................................................................................................. 2 List of Figures ....................................................................................................................... 5 List of Tables ........................................................................................................................ 6 Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................... 9 Executive Summary ............................................................................................................ 10 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................. 18 1.1 Background.......................................................................................................... -

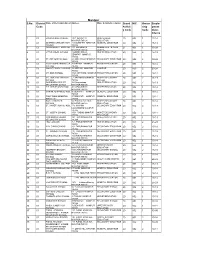

Manipur S.No

Manipur S.No. District Name of the Establishment Address Major Activity Description Broad NIC Owner Emplo Code Activit ship yment y Code Code Class Interva l 101OKLONG HIGH SCHOOL 120/1 SENAPATI HIGH SCHOOL 20 852 1 10-14 MANIPUR 795104 EDUCATION 201BETHANY ENGLISH HIGH 149 SENAPATI MANIPUR GENERAL EDUCATION 20 852 2 15-19 SCHOOL 795104 301GOVERNMENT HOSPITAL 125 MAKHRALUI HUMAN HEALTH CARE 21 861 1 30-99 MANIPUR 795104 CENTRE 401LITTLE ANGEL SCHOOL 132 MAKHRELUI, HIGHER EDUCATION 20 852 2 15-19 SENAPATI MANIPUR 795106 501ST. ANTHONY SCHOOL 28 MAKHRELUI MANIPUR SECONDARY EDUCATION 20 852 2 30-99 795106 601TUSII NGAINI KHUMAI UJB 30 MEITHAI MANIPUR PRIMARY EDUCATION 20 851 1 10-14 SCHOOL 795106 701MOUNT PISGAH COLLEGE 14 MEITHAI MANIPUR COLLEGE 20 853 2 20-24 795106 801MT. ZION SCHOOL 47(2) KATHIKHO MANIPUR PRIMARY EDUCATION 20 851 2 10-14 795106 901MT. ZION ENGLISH HIGH 52 KATHIKHO MANIPUR HIGHER SECONDARY 20 852 2 15-19 SCHOOL 795106 SCHOOL 10 01 DON BOSCO HIGHER 38 Chingmeirong HIGHER EDUCATION 20 852 7 15-19 SECONDARY SCHOOL MANIPUR 795105 11 01 P.P. CHRISTIAN SCHOOL 40 LAIROUCHING HIGHER EDUCATION 20 852 1 10-14 MANIPUR 795105 12 01 MARAM ASHRAM SCHOOL 86 SENAPATI MANIPUR GENERAL EDUCATION 20 852 1 10-14 795105 13 01 RANGTAIBA MEMORIAL 97 SENAPATI MANIPUR GENERAL EDUCATION 20 853 1 10-14 INSTITUTE 795105 14 01 SAINT VINCENT'S 94 PUNGDUNGLUNG HIGHER SECONDARY 20 852 2 10-14 SCHOOL MANIPUR 795105 EDUCATION 15 01 ST. XAVIER HIGH SCHOOL 179 MAKHAN SECONDARY EDUCATION 20 852 2 15-19 LOVADZINHO MANIPUR 795105 16 01 ST. -

List of Successful Candidates in Manipur

List of successful candidates in Manipur Ac Ac Name Party Candidate Name No. Nationalist 1 Khundrakpam THOKCHOM NAVAKUMAR SINGH Congress Party Indian National 2 Heingang NONGTHOMBAM BIREN Congress Manipur People's 3 Khurai DR. NGAIRANGBAM BIJOY SINGH Party Nationalist THANGJAM NANDAKISHOR 4 Khetrigao Congress Party SINGH Indian National 5 Thongju BIJOY KOIJAM Congress Indian National 6 Keirao MD. ALAUDDIN KHAN Congress Manipur People's 7 Andro THOUNAOJAM SHYAMKUMAR Party Communist Party 8 Lamlai PHEIROIJAM PARIJAT of India Nationalist 9 Thangmeiband RADHABINOD KOIJAM Congress Party Indian National LAISHRAM NANDAKUMAR 10 Uripok Congress SINGH Indian National DR. KHWAIRAKPAM LOKEN 11 Sagolband Congress SINGH Indian National SHRI LANGPOKLAKPAM 12 Keishamthong Congress JAYENTAKUMAR SINGH Indian National IRENGBAM HEMOCHANDRA 13 Singjamei Congress SINGH Indian National SHRI ELANGBAM KUNJESWAR 14 Yaiskul Congress SINGH 15 Wangkhei Indian National YUMKHAM ERABOT SINGH Congress Communist Party 16 Sekmai DR. HEIKHAM BORAJAO of India Indian National WANGKHEIMAYUM 17 Lamsang Congress BRAJABIDHU Indian National DR. SAPAM BUDHICHANDRA 18 Konthoujam Congress SINGH SAPAM KUNJAKESWOR (KEBA) 19 Patsoi Independent SINGH Manipur People's 20 Langthabal OKRAM JOY SINGH Party Naoriya Manipur People's 21 R. K. ANAND Pakhanglakpa Party Nationalist 22 Wangoi SALAM JOY SINGH Congress Party Indian National DR. KHUMUJAM RATAN KUMAR 23 Mayang Imphal Congress SINGH Indian National SHRI NAMEIRAKPAM LOKEN 24 Nambol Congress SINGH Manipur People's 25 Oinam IRENGBAM IBOHALBI Party Indian National 26 Bishenpur KONTHOUJAM GOVINDAS Congress Indian National 27 Moirang M. MANINDRA Congress Indian National 28 Thanga TONGBRAM MANGIBABU SINGH Congress Communist Party 29 Kumbi NINGTHOUJAM MANGI of India Rashtriya Janata 30 Lilong MD. HELALUDDIN KHAN Dal Indian National 31 Thoubal SHRI OKRAM IBOBI SINGH Congress Indian National KEISHAM MEGHACHANDRA 32 Wangkhem Congress SINGH Indian National 33 Heirok M. -

MSME) MANIPUR ( EM Part-II Filed As on 2013-2014

DIRECTORY OF MICRO, SMALL & MEDIUM ENTERPRISES (MSME) MANIPUR ( EM Part-II filed as on 2013-2014 ) VOLUME-I Department of Commerce & Industries Government of Manipur Govvindas Konthoujam Minister Commerce & Industries Veterinary & An imal Husban dry and Sericulture Manipur MESSAGE I am happy to learn that the Directorate of Commerce & Industries, Manipur, is publishing a Directory of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs). The importance of a Directory is needless to mention as all the vital information of an enterprise can be known from this Directory easily. The tireless efforts and endeavours rendered by S/Shri M. Lyanchinpao (Statistical Supervisor), N. Rupachandra Singh (Statistical Supervisor), Ch. Khogendra Singh (Statistical Supervisor) and M. Kunjeshwar Meetei (Extension Officer) and RV. John, OSD (Nucleus Cell) under the guidance of Shri B. John Tlangtinkhuma, IAS, Director of Commerce & Industries, Manipur for printing of the Directory is highly appreciated. It may not be out of place to mention that the valuable contribution made by Shri S. Birendra Singh, former Functional Manager (KVI), OSD Handicrafts/Nucleus Cell who took the initial role to publish this Directory, deserves special appreciation from all the hearts involved in the production of such an important Directory. I hope that this Directory will be useful for the Entrepreneurs, Econoomists and Scholars for various purposes as growth of MSMEs, its employment, production, etc. are included in this Directory with graphical presentation and tabulation. I wish the publication all success. (Govindas Konthoujam) Lungmuana Lakher IAS Prrincipal Secretary(C&I) FOREWORD It gives me immense pleasure to learn that the Directorate of Commerce & Industries, Manipur, is bringing out a Directory of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSME) for the years 2007-08 to 2013-14. -

47341-003: South Asia Subregional

Updated Resettlement Plan Project Number: 47341-003 Loan Number: 3690 April 2019 India: South Asia Subregional Economic Cooperation Road Connectivity Investment Program-Tranche 2 Imphal-Moreh (Package-1) Road Section from Km 330.00 Imphal to Km. 350.00 Wangjing Prepared by Ministry of Road Transport and Highways, Government of India for the Asian Development Bank. This updated resettlement plan is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section of this website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (As of 31 March 2019) Currency Unit – Indian Rupee (INR) INR 1.00 = 0.014 USD USD 1.00 = INR 69 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank BSR – Basic Schedule of Rates DC – District Collector DP – Displaced person EA – Executing Agency GOI – Government of India GRC – Grievance Redressal Committee IA – Implementing Agency IAY – Indira Awaas Yojana IPP – Indigenous Peoples Plan LA – Land acquisition L&LRO – Land and Land Revenue Office RFCT in – The Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land LARR Act Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, 2013 – 2013 LVC – Land Valuation -

District Report THOUBAL

Baseline Survey of Minority Concentrated Districts District Report THOUBAL Study Commissioned by Ministry of Minority Affairs Government of India Study Conducted by Omeo Kumar Das Institute of Social Change and Development: Guwahati VIP Road, Upper Hengerabari, Guwahati 781036 1 ommissioned by the Ministry of Minority CAffairs, this Baseline Survey was planned for 90 minority concentrated districts (MCDs) identified by the Government of India across the country, and the Indian Council of Social Science Research (ICSSR), New Delhi coordinated the entire survey. Omeo Kumar Das Institute of Social Change and Development, Guwahati has been assigned to carry out the Survey for four states of the Northeast, namely Assam, Arunachal Pradesh, Meghalaya and Manipur. This report contains the results of the survey for Thoubal district of Manipur. The help and support received at various stages from the villagers, government officials and all other individuals are most gratefully acknowledged. ■ Omeo Kumar Das Institute of Social Change and Development is an autonomous research institute of the ICSSR, New delhi and Government of Assam. 2 CONTENTS BACKGROUND....................................................................................................................................8 METHODOLOGY.................................................................................................................................9 TOOLS USED ......................................................................................................................................10 -

Manipur Cover 20Mm Spine:Karmicbill Creedexhibit.Qxd 9/13/2010 2:44 PM Page 1

manipur_cover_20mm spine:KarmicBill_CreedExhibit.qxd 9/13/2010 2:44 PM Page 1 JaCKbooT dEMoCrACy the Northeast of india has always existed on the periphery of the nation’s consciousness, and in the footnotes of the narrative of growth, progress and development. in a region where lawlessness, rape, murder, army excesses, arbitrary detention, torture and repression are the order of the day, the man in uniform is a formidable and fearsome figure. the AFSPA that is in force here is one of the most draconian laws that Parliament has enacted in its legislative history. the law has fostered a climate in MANiPUr which the agents of law enforcement use excessive M A force at their command and set a pattern of N i apparently unlawful killings of “suspected” civilians. P iN tHE SHAdoW oF U the AFSPA gives security forces unlimited powers to r i carry out operations with impunity once an area is N declared “disturbed”. t H E S And the state of Manipur has been groaning under H A the heels of this repressive law for far too long now, d o aFsPa where the dreaded legislation has brought with it W iNdEPENdENt PEoPlE’S tales of untold sufferings — midnight knocks, o F arbitrary searches, forced captures, innumerable A tribUNAl rEPort incidents of torture, un-notified detentions, sudden F S P oN HUMAN riGHtS disappearances and rapes — more often just on the A basis of mere suspicion, and ostensibly to ‘maintain ViolAtioNS iN MANiPUr public order’. to understand the anguish of Manipuri people today, one must know the history of the AFSPA, which is nothing but a replica of the 1942 CritiqUE oF JUStiCE JEEVAN rEddy ordinance framed by the british to control the rising rEPort oN AFSPA tide of indian nationalism. -

From Lilong Bridge Village No

List of affected pattadars for direct purchase of land for land for consruction/expansion of National Highway No. 102(39) from Lilong Bridge Village No. 28 - Thoubal Achouba Sheet No. 4 Sl. Name of the affected pattadars Patta No. Dag No. Affected Land Standing Standing Total Classif- No. area (in Value properties properties Amount ication hect) without with solatium solatium 1 i) Rajkumari (N) Dhanisana Devi D/o (L) 358 3080 0.0061 787890 1463180 2926360 3714250 Ingkhol Sanatomba Singh of Thoubal Achouba ii)R.K. Ghandhishana Singh S/o (L) Sanatomba Singh of Thoubal Achouba iii) R.K. Joychandra Singh S/o (L) Sanatomba Singh of Thoubal Achouba iv) R.K. Dorensana Singh S/o (L) Sanatomba Sing of Thoubal Achouba 1(A) i) R.K. (N) Dhanisana Devi D/o (L) 873 3079 0.0108 1394953 0 0 1394953 Ingkhol Sanatomba Singh of Thoubal Achouba ii) R.K. Ghandhishana Singh S/o (L) Sanatomba Singh of Thoubal Achouba iii) R.K. Joychandra Singh S/o (L) Sanatomba Singh of Thoubal Achouba iv) R.K. Dorensana Singh S/o (L) Sanatomba Sing of Thoubal Achouba 2 Waikhom (O) Sakhitombi Devi W/o (L) 872 3077 0.0079 1020383 1394028 2788056 3808439 Ingkhol Biren Singh ii) Waikhom Netrajit Singh S/o (L) Mani Singh of Thoubal Bazar 3 i) Akoijam Priyokumar Singh S/o (L) 1029 3075 0.0050 645812 1135540 2271080 2916892 Ingkhol Ibomcha Singh ii) Akoijam Pratap Singh S/o (L) Ibomcha Singh of Thoubal Bazar 4 i) Akoijam Gandhi Singh S/o (L) Ibochouba 50 3174 0.0055 710393 637337 1274674 1985067 Ingkhol Singh ii) Akoijam Ranjit Singh S/o (L) Ibochouba Singh iii) Akoijam Mocha Singh S/o (L) Ibochouba Singh iv) Akoijam Opendro Singh S/o (L) Ibochouba Singh of Thoubal Bazar 5 i) Leitanthem Jiten Singh S/o (L) Ibopishak 613 3082 0.0072 929969 1479066 2958132 3888101 Ingkhol Singh of Thoubal Achouba ii) L. -

SASEC ROAD CONNECTIVITY INVESTMENT PROGRAM – TRANCHE 2 Two Laning of Imphal Moreh Section of NH 39 (Package II) from Km 350.000 to Km 395.680 in the State of Manipur

Social Monitoring Report Semiannual Report (October – December 2018) June 2019 IND: SASEC ROAD CONNECTIVITY INVESTMENT PROGRAM – TRANCHE 2 Two laning of Imphal Moreh Section of NH 39 (Package II) from Km 350.000 to Km 395.680 in the State of Manipur Prepared by G.R. Infra Projects Limited for National Highways & Infrastructure Development Corporation Ltd., Ministry of Road Transport & Highways, Government of India and the Asian Development Bank. This social monitoring report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. National Highways & Infrastructure Development Corporation Ltd. (A company under Ministry of Road Transport & Highways) (Government of India) Two laning of Imphal Moreh Section of NH 39 (Package II) from Km 350.000 to Km 395.680 in the State of Manipur under ADB assisted SASEC Regional Connectivity Investment Program (SRCIP) Loan No. 3690-IND Tranche-2 Semi-Annual Social Monitoring Report October-December 2018 Authority Engineer M/s FEEDBACK INFRA PRIVATE LIMITED EPC Contractor M/s G R Infra Projects Limited Asian Highway No. 1 Semi-Annual Social Monitoring Report October-December 2018 CONTENTS Sl. No. Description Pages 1.0. Section:Introduction 1-3 1.1. -

List of Affiliated Schools

School List recognised by the Board of Secondary Education, Manipur Code no School Name 57293 2/LT. THOMAS MEMORIAL SCHOOL, KAMPHASOM, UKL 21733 A. JALIL HIGH SCHOOL, KHERGAO 43352 A. RUDRA HIGH SCHOOL, TRONGLAOBI, MOIRANG 36091 ABDUL ALI HIGH MADRASSA, LILONG 55993 ACHAN ENGLISH SCHOOL, UKHRUL 21743 ACHANBIGEI HIGH SCHOOL, B.P.O. ACHANBIGEI 10011 ADIMJATI HIGH SCHOOL, IMPHAL 10723 ADIMJATI LITTLE ENGLISH SCHOOL,IMPHAL 37253 ADVANCE LEARNER SCHOOL, HEIROK 47793 ADVANCE PUBLIC SCHOOL, MOIRANG 64243 AGAPE HIGH SCHOOL, SANGAIKOT, CCPUR 28331 AHMEDABAD HIGH SCHOOL, JIRIBAM 98741 AIMOL CHINGNUNGHUT HIGH SCHOOL, CHANDEL 15613 AJAD ENGLISH SCHOOL, NAMBOL 88381 AKHUI HIGH SCHOOL, TAMENGLONG 37773 AL - EDDEEN ENGLISH SCHOOL, HEIBONG MAKHONG , M/IMPHAL 19413 ALBERTS ENGLISH SCHOOL, SINGJAMEI 53863 ALICE CHRISTIAN HR. SEC. SCHOOL, P.O. UKHRUL 17463 ALPHA B.C.I. MEMORIAL ACADEMY, THANGMEIBAND 57283 ALPHA CHRISTIAN HIGH SCHOOL, KACHAI VILLAGE 32452 AMUBA HIGH SCHOOL, B.P.O. KHANGABOK 43443 AMUSANA HIGH SCHOOL, KEINOU 36223 AMUTOMBI DIVINE LIFE ENG. SCHOOL, WABAGAI 95393 ANALLON CHRISTIAN INSTITUTE, LAMBUNG, CHANDEL 32643 ANANDA PURNA SCHOOL, THOUBAL (TOMJING) 21201 ANANDA SINGH HR. SECONDARY ACADEMY, IMPHAL 29121 ANDRO HIGH SCHOOL, ANDRO IMPHAL EAST DISTRICT 21552 ANDRO HIGH SCHOOL, B.P.O. ANDRO 16383 ANGAHAL HIGHER SECONDARY SCHOOL, WANGOI 97943 ANGAM MEMORIAL SCHOOL, LIWACHANGNING 46763 ANITA STANDARD HIGH SCHOOL, KWAKTA 36573 ANK ENGLISH ACADEMY, LANGMEIDONG 26533 ANTARTIC ENGLISH SCHOOL, YAIRIPOK 75903 APEX CHRISTIAN HIGH SCHOOL, MOTBUNG 87353 APOU KADING HIGH SCHOOL, TAMEI 38761 ARONG HIGH SCHOOL, THOUBAL 64253 ASSEMBLIES OF GOD HIGH SCHOOL, P.O. CCPUR 18213 ASSEMBLIES OF GOD SCHOOL, LANGOL 54013 ASUI MEMORIAL SCHOOL, WUNGHON VILLAGE, UKHRUL 79451 AWANG LONGA KOIRENG GOVT. -

District Survey Report for Thoubal District (Manipur State) For

DISTRICT SURVEY REPORT FOR THOUBAL DISTRICT (MANIPUR STATE) FOR A. SAND MINING OR RIVER BED MINING B. MINERALS OTHER THAN SAND MINING OR RIVER BED MINING (PEBBLE FOR CRUSHING/OPENCAST SURFACE MINING) (Revision 00) Prepared under A] Appendix –X of MoEFCC, GoI notification S.O. 141(E) dated 15.1.2016 B] Sustainable Sand Mining Guidelines C] MoEFCC, GoI notification S.O. 3611(E) dated 25.07.2018 D]Enforcement & Monitoring Guidelines, January 2020, MoEFCC, GoI Declaration In compliance to the notifications, guidelines issued by Ministry of Environment, Forest & Climate Change, Government of India, New Delhi, District Survey Report (Rev. 00) for Thoubal district is prepared and published. Place : Thoubal Date : District Collector, Thoubal Secretary (Water Resources Department) Govt. of Manipur, Thoubal, Manipur Index Sr. Description Page No. No. 1 District Survey Report for Sand Mining Or River Bed Mining 1-52 1.0 Introduction 2 Brief Introduction of Thoubal district 2 Salient Features of Thoubal District 8 2.0 Overview of Mining Activity in the district 10 3.0 List of the Mining Leases in the district with Location, area 12 and period of validity Location of Sand Ghats along the Rivers in the district 13 4.0 Detail of Royalty/Revenue received in last three years from 14 Sand Scooping activity 5.0 Details of Production of Sand or Bajri or minor mineral in last 14 three Years 6.0 Process of Deposition of Sediments in the rivers of the 14 District Stream Flow Guage Map for rivers in Thoubal district 18 Siltation Map for rivers in Thoubal district 19 7.0 General Profile of the district 20 8.0 Land Utilization Pattern in the District : Forest, Agriculture, 24 Horticulture, Mining etc. -

Census of India 2011

Census of India 2011 MANIPUR SERIES-15 PART XII-B DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK THOUBAL VILLAGE AND TOWN WISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT (PCA) DIRECTORATE OF CENSUS OPERATIONS MANIPUR S E MANIPUR r e N v T i A R F l r Im o a THOUBAL DISTRICT m P H C b P p M A h I u a I o 1 0 1 l L h A T I r R i E T T l T R A S D I S Kilometrws i T v F I e r LILONGr o C ! (THOUBAL) (N P) m Itok River D I T ! (MAJOR PART) m o p K I LILONG N a R h s I SAMUROU (N P) H a om l H S (MINOR PART) 1 S K 0 hu 2 l T le R n YAIRIPOK LILONG SUB-DIVISION ! R i ! (N P) b n T a WANGKHEM I h SIKHONG A C l SH SEKMAI e u r (N P) S T r ive T bal R ou ! ! I h ! THOUBAL T MOIJING (M CI) ! P THOUBAL D IRONG CHESABA KHEKMAN ! ! KHANGABOK ! LEISANGTHEM WANGJING T (N P) r MAIBAM KONJIL ! e r v r e i e ! i v iv R ng R o T Ar R r S g u in p j i ng n a a W M ! HEIROK ! E IKOP (N P) PAT SANGAIYUMPHAM W ! TENTHA From Imph THOUBAL SUB-DIVISION al C L I N D I A 2 0 1 S H A H !WABAGAI N ! I H HIYANGLAM I KAKCHING KAKCHING (M Cl) P S ! r R e e kmai Ri v ver i S R H R M l a PUMLEN h LANGMEIDONG p PAT ! m I I T KAKCHING SUB-DIVISION T ! l Chande C ARONG NONGMAIKHONG To eh I or M S o H T I S R T ! ! WANGOO D S KAKCHING KHUNOU Area (in Sq.