EMD Mid-Year Leadership Meeting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Application of Organic Petrography in North American Shale Petroleum Systems: a Review

International Journal of Coal Geology 163 (2016) 8–51 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect International Journal of Coal Geology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ijcoalgeo Application of organic petrography in North American shale petroleum systems: A review Paul C. Hackley a, Brian J. Cardott b a U.S. Geological Survey, MS 956 National Center, 12201 Sunrise Valley Dr, Reston, VA 20192, USA b Oklahoma Geological Survey, 100 E. Boyd St., Rm. N-131, Norman, OK 73019-0628, USA article info abstract Article history: Organic petrography via incident light microscopy has broad application to shale petroleum systems, including Received 13 April 2016 delineation of thermal maturity windows and determination of organo-facies. Incident light microscopy allows Received in revised form 10 June 2016 practitioners the ability to identify various types of organic components and demonstrates that solid bitumen Accepted 13 June 2016 is the dominant organic matter occurring in shale plays of peak oil and gas window thermal maturity, whereas Available online 16 June 2016 oil-prone Type I/II kerogens have converted to hydrocarbons and are not present. High magnification SEM obser- Keywords: vation of an interconnected organic porosity occurring in the solid bitumen of thermally mature shale reservoirs Organic petrology has enabled major advances in our understanding of hydrocarbon migration and storage in shale, but suffers Thermal maturity from inability to confirm the type of organic matter present. Herein we review organic petrography applications Shale petroleum systems in the North American shale plays through discussion of incident light photographic examples. In the first part of Unconventional resources the manuscript we provide basic practical information on the measurement of organic reflectance and outline Vitrinite reflectance fluorescence microscopy and other petrographic approaches to the determination of thermal maturity. -

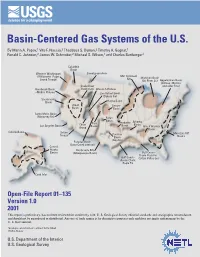

Basin-Centered Gas Systems of the U.S. by Marin A

Basin-Centered Gas Systems of the U.S. By Marin A. Popov,1 Vito F. Nuccio,2 Thaddeus S. Dyman,2 Timothy A. Gognat,1 Ronald C. Johnson,2 James W. Schmoker,2 Michael S. Wilson,1 and Charles Bartberger1 Columbia Basin Western Washington Sweetgrass Arch (Willamette–Puget Mid-Continent Rift Michigan Basin Sound Trough) (St. Peter Ss) Appalachian Basin (Clinton–Medina Snake River and older Fms) Hornbrook Basin Downwarp Wasatch Plateau –Modoc Plateau San Rafael Swell (Dakota Fm) Sacramento Basin Hanna Basin Great Denver Basin Basin Santa Maria Basin (Monterey Fm) Raton Basin Arkoma Park Anadarko Los Angeles Basin Chuar Basin Basin Group Basins Black Warrior Basin Colville Basin Salton Mesozoic Rift Trough Permian Basin Basins (Abo Fm) Paradox Basin (Cane Creek interval) Central Alaska Rio Grande Rift Basins (Albuquerque Basin) Gulf Coast– Travis Peak Fm– Gulf Coast– Cotton Valley Grp Austin Chalk; Eagle Fm Cook Inlet Open-File Report 01–135 Version 1.0 2001 This report is preliminary, has not been reviewed for conformity with U. S. Geological Survey editorial standards and stratigraphic nomenclature, and should not be reproduced or distributed. Any use of trade names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U. S. Government. 1Geologic consultants on contract to the USGS 2USGS, Denver U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey BASIN-CENTERED GAS SYSTEMS OF THE U.S. DE-AT26-98FT40031 U.S. Department of Energy, National Energy Technology Laboratory Contractor: U.S. Geological Survey Central Region Energy Team DOE Project Chief: Bill Gwilliam USGS Project Chief: V.F. -

Unconventional Energy Resources: 2007–2008 Review

Natural Resources Research (Ó 2009) DOI: 10.1007/s11053-009-9094-0 Unconventional Energy Resources: 2007–2008 Review American Association of Petroleum Geologists, Energy Minerals Division1 Received 22 September 2008; accepted 26 March 2009 This paper summarizes five 2007–2008 resource commodity committee reports prepared by the Energy Minerals Division (EMD) of the American Association of Petroleum Geologists. Current United States and global research and development activities related to gas hydrates, gas shales, geothermal resources, oil sands, and uranium resources are included in this review. These commodity reports were written to advise EMD leadership and mem- bership of the current status of research and development of unconventional energy resources. Unconventional energy resources are defined as those resources other than conventional oil and natural gas that typically occur in sandstone and carbonate rocks. Gas hydrate resources are potentially enormous; however, production technologies are still under development. Gas shale, geothermal, oil sand, and uranium resources are now increasing targets of exploration and development, and are rapidly becoming important energy resources that will continue to be developed in the future. KEY WORDS: Gas hydrate, gas shale, geothermal, oil sands, uranium, unconventional energy resources. INTRODUCTION the EMD leadership. The complete set of committee reports is available to EMD members at http:// Peter D. Warwick2,3 emd.aapg.org/members_only/. This paper updates the 2006 EMD review published in this journal The increasing demand for and continuing (American Association of Petroleum Geologists, depletion of accessible oil and gas resources are Energy Minerals Division, 2007) and is presented causing greater dependence on energy minerals such here as a service to the general geologic community. -

Update on North America Shale-Gas Exploration and Development

CHAPTER ONE Update on North America Shale-Gas Exploration and Development DAVID G. HILL 1, JOHN B. CURTIS 2, PAUL G. LILLIS 3 1. EnCana Oil & Gas (USA) Inc., Denver Colorado 80202; 2. Department of Geology and Geological Engineering, Colorado School of Mines, Golden, Colorado 80401; 3. U.S. Geological Survey, Denver, Colorado 80225 ABSTRACT In the oil and gas industry, shale has overcome its stigma as an odd unconventional hydrocarbon reservoir to become one of the most sought-after resource plays in North America. Spurred by develop - ment of the Barnett Shale in the Fort Worth Basin, U.S. drilling and exploration for this unique play type is at an all time high at year-end 2006. Recent shale specific consortia, workshops, symposia and confer - ences reflect this increased emphasis on shale plays. Shale-gas plays have emerged as commercially viable and encouraging exploration is ongoing in many basins in North America. Hydrocarbon production from shale-gas systems has a long and important history in North America. The first commercial U.S. natural gas production (1821) came from organic-rich Devonian shale in the Appalachian basin. The first commercial U.S. oil production from shale (1862) came from the Upper Cre - taceous Pierre Shale in Colorado. Both plays are still producing today. With the recent growth of shale-gas plays, defining and classifying shale reservoirs has become increasingly complex. Including both gas and oil productive systems and expanding the definition to include fine-grained source rocks creates a more encompassing taxonomy. Shale-gas systems are generally unconventional, self-sourced, continuous-type accumulations (biogenic, thermogenic or combined bio - genic-thermogenic gas accumulations). -

Shale Gas Plays in North America – a Review

Canadian Energy Research Institute North American Natural Gas Market Dynamics: Shale Gas Plays in North America – A Review Paul Kralovic Study No. 123 – Section I February 2011 Relevant • Independent • Objective NORTH AMERICAN NATURAL GAS MARKET DYNAMICS: SHALE GAS PLAYS IN NORTH AMERICA – A REVIEW North American Natural Gas Market Dynamics: Shale Gas Plays in North America – A Review Copyright © Canadian Energy Research Institute, 2011 Sections of this study may be reproduced in magazines and newspapers with acknowledgement to the Canadian Energy Research Institute Study No. 123 ISBN 1-896091-97-0 Author: Paul Kralovic* *Paul Kralovic is an external consultant and is the Director of Calgary-based Kralovic Economics Inc. Acknowledgements: The author of this report would like to extend his thanks and gratitude to everyone involved in the production and editing of the material, including, but not limited to George Eynon, Megan Murphy and Peter Howard CANADIAN ENERGY RESEARCH INSITTUTE 150, 3512 – 33 Street NW Calgary, Alberta T2L 2A6 Canada www.ceri.ca February 2011 Printed in Canada North American Natural Gas Market Dynamics: iii Shale Gas Plays in North America – A Review Table of Contents LIST OF FIGURES .............................................................................................................................. v LIST OF TABLES ................................................................................................................................ vii CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION AND REPORT STRUCTURE ............................................................. -

Natural Gas Production from “Shale” Formations

Natural gas production from “shale” formations (fine-grained sedimentary rocks with relatively low permeability that can be rich sources of petroleum and natural gas) is one of the most rapidly-growing trends in U.S. domestic energy exploration and production. In some cases, this fast expansion has resulted in natural gas drilling and production activity in parts of the country that have seen little or no activity of this type in the recent past. “Natural Gas from Shale” explains the basics, including what shale gas is, where it’s found, why it’s important, how it’s produced, and challenges associated with production. Also included are a list of frequently asked questions, a glossary of major terms, and a list of resources and links for additional information. Office of Fossil Energy NATURAL GAS FROM SHALE: Questions and Answers What is shale gas? Basically, it is natural gas – primarily methane – found in shale formations, some of which were formed 300-million-to-400-million years ago during the Devonian period of Earth’s history. The shales were deposited as fine silt and clay particles at the bottom of relatively enclosed bodies of water. At roughly the same time, primitive plants were forming forests on land and the first amphibians were making an appearance. Some of the methane that formed from the organic matter buried with the sediments escaped into sandy rock layers adjacent to the shales, forming conventional accumulations of natural gas which are relatively easy to extract. But some of it remained locked in the tight, low permeability shale layers, becoming shale gas. -

Deep Shale Oil and Gas Deep Shale Oil and Gas

DEEP SHALE OIL AND GAS DEEP SHALE OIL AND GAS JAMES G. SPEIGHT, PhD, DSc CD&W Inc., Laramie, WY, United States AMSTERDAM • BOSTON • HEIDELBERG • LONDON NEW YORK • OXFORD • PARIS • SAN DIEGO SAN FRANCISCO • SINGAPORE • SYDNEY • TOKYO Gulf Professional Publishing is an imprint of Elsevier Gulf Professional Publishing is an imprint of Elsevier 50 Hampshire Street, 5th Floor, Cambridge, MA 02139, United States The Boulevard, Langford Lane, Kidlington, Oxford, OX5 1GB, United Kingdom © 2017 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Details on how to seek permission, further information about the Publisher’s permissions policies and our arrangements with organizations such as the Copyright Clearance Center and the Copyright Licensing Agency, can be found at our website: www.elsevier.com/permissions. This book and the individual contributions contained in it are protected under copyright by the Publisher (other than as may be noted herein). Notices Knowledge and best practice in this field are constantly changing. As new research and experience broaden our understanding, changes in research methods, professional practices, or medical treatment may become necessary. Practitioners and researchers must always rely on their own experience and knowledge in evaluating and using any information, methods, compounds, or experiments described herein. In using such information or methods they should be mindful of their own safety and the safety of others, including parties for whom they have a professional responsibility. -

Gas Shales Report 2009 Mid-Year Mtg Revised

EMD Annual Leadership Meeting November 12, 2009 Gas Shale Committee Report Brian Cardott, Harris Cander, Michael Cameron, Neil Fishman (Vice-Chairs) 1. Active Gas-Shale Plays The EIA Active U.S. Gas Shale Plays, Barnett, Fayetteville, Haynesville, and Marcellus maps are available at http://www.eia.doe.gov/pub/oil_gas/natural_gas/analysis_publications/maps/ maps.htm. Recent summary reports are as follows: Stevens, S., and V. Kuuskraa, 2009, Gas Shale–1: Seven plays dominate North America activity: Oil & Gas Journal, v. 107.36, p. 39-49. (Barnett, Fayetteville, Haynesville, Horn River, Marcellus, Montney, Woodford) Kuuskraa, V., and S. Stevens, 2009, Gas shale–2: Lessons learned help optimize development: Oil & Gas Journal, v. 107.37, p. 52-57. Stevens, S., M. Godec, and K. Moodhe, 2009, Gas shale–Conclusion: New plays emerge, although environmental issues arise: Oil & Gas Journal, v. 107.39, p. 39-45. There are too many potential gas shales to describe each in detail. Below are a few highlights. (a) Fort Worth Basin, Texas: Barnett Shale (Mississippian). The Barnett Shale is still the most active gas-shale play in the United States. The EIA Barnett Shale map is available at http://www.eia.doe.gov/pub/oil_gas/natural_gas/analysis_publications/map s/maps.htm. According to the Texas Railroad Commission web site (http://www.rrc.state.tx.us/data/fielddata/barnettshale.pdf) as of September 8, 2009 there were a total of 12,135 Barnett Shale gas wells and 3,521 permitted locations in the Newark East Field (discovery date, October 15, 1981) of the Fort Worth Basin. The field produces in 21 counties. -

Report, Only Shale- Understanding of the Geology, Petrophysics, and Geomechanics Gas Assessment Units and Cells Are Shown

National Assessment of Oil and Gas Project Map of Assessed Shale Gas in the United States, 2012 Digital Data Series 69–Z Plate 1 CANADA Seattle Tacoma Spokane WASHINGTON Vancouver Portland MAINE MONTANA NORTH DAKOTA Antrim Eugene Duluth OREGON VERMONT MINNESOTA NEW HAMPSHIRE Minneapolis-Saint Paul NEW YORK WISCONSIN Boston Syracuse SOUTH DAKOTA Rochester MASSACHUSETTS Springfield IDAHO MICHIGAN Providence Buffalo Marcellus Devonian Antrim Continuous Gas AU HartfordRHODE ISLAND Utica Shale Gas AU CONNECTICUT WYOMING Flint Grand Rapids Milwaukee Lansing Niobrara Chalk AU Detroit Interior Marcellus AU New York City NEW JERSEY Toledo IOWA Chicago Cleveland PENNSYLVANIA Trenton Youngstown Utica Akron Foldbelt Marcellus AU Salt Lake City Philadelphia NEBRASKA UNITED STATES Fort Wayne Sacramento Omaha Northwestern NEVADA UTAH Ohio Shale AU Western Margin Marcellus AU Concord OHIO Oakland Columbus INDIANA Dayton San Jose ILLINOIS Indianapolis Cane Creek Shale Gas Denver Gothic, Chimney Rock, Devonian to Mississippian New Albany Continuous Gas AU Hovenweep Shale Gas Cincinnati WEST VIRGINIA Devonian Siltstone and Shale AU Covington Niobrara CALIFORNIA Kansas City Marcellus Richmond COLORADO Saint Louis Louisville VIRGINIA Newport News-Hampton Appalachian Devonian Norfolk KANSAS MISSOURI Gothic, Hovenweep KENTUCKY Roanoke Fayetteville Shale Gas– Western Arkansas Basin Margin AU Las Vegas New Albany Chattanooga Winston-Salem Woodford Fayetteville Caney Shale Gas AU Fayetteville Shale Gas– TENNESSEE Chattanooga NORTH CAROLINA Nashville Knoxville Thirteen -

EMD Mid-Year Leadership Meeting November 14, 2007 Gas Shale Committee Report Brian Cardott, Chairman

EMD Mid-Year Leadership Meeting November 14, 2007 Gas Shale Committee Report Brian Cardott, Chairman 1. Active Gas Shale Plays Many black shale hydrocarbon source rocks across the U.S. and Canada are currently being evaluated as gas shales. There are too many potential gas shales to describe each in detail. Below are a few highlights. (a) Fort Worth Basin, Texas: Barnett Shale (Mississippian). The Barnett Shale is still the most active gas-shale play in the United States. According to the Texas Railroad Commission web site (http://www.rrc.state.tx.us/divisions/og/statistics/fielddata/barnettshale.pdf) as of August 15, 2007 there were a total of 6,519 Barnett Shale gas wells and 4,051 permitted locations in the Newark East Field of the Fort Worth Basin. During calendar year 2006, 686 BCF gas was produced from the field, accounting for 12% of Texas gas production. Of a total of 161 operators in the Newark East Field, the top 10 operators are: (1) Devon Energy Production Co. (2) XTO Energy Inc. (3) Chesapeake Operating Inc. (4) EOG Resources Inc. (5) Encana Oil and Gas (USA) Inc. (6) Burlington Resources O&G Co. LP (7) Range Production Co. (8) J-W Operating Co. (9) Denbury Onshore, LLC (10) Quicksilver Resources Inc. (b) Arkoma Basin, Arkansas: Fayetteville Shale (Mississippian). According to the Arkansas Oil and Gas Commission web site (http://www.aogc.state.ar.us/Fayprodinfo.htm), there are a total of 453 active Fayetteville Shale wells (completed or permitted, as of August 31, 2007). A map of Fayetteville Shale wells is available at http://www.geostor.arkansas.gov/apps/aogc/index.htm. -

3. Production of Marcellus Shale Gas

3. Production of Marcellus Shale Gas Production of the modern Marcellus Shale gas play began in Administration (NOAA), the National Institutes of Health (NIH), 2005. Although the use of the word “play” to describe a resource National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), and may sound frivolous, in oil and gas exploration, play is a legiti- DOE provide similar information. mate term defi ned as a group of drilling prospects with a geo- Thirty years ago, shale gas was considered a marginal logically similar source, reservoir and trap, which control gas resource that could not be physically produced in large quanti- migration, accumulation, and storage (Patchen, 1996). In more ties, and even if it could, the economics would be awful. The practical terms, a play means fi nding out where other people are drilling industry wouldn’t go near it, except in very limited areas drilling successfully for gas or oil and drilling as close to that or as a secondary target. Yet, the government persisted in collect- place as possible. Thus, a successful oil or gas well in one loca- ing research data on the shales, completing a resource assessment tion brings in many others. and characterizing the rock properties. Even though no one knew The twenty-fi rst-century boom in shale gas drilling did not how to produce the resource at the time, it represented such an simply come about as a bolt from the blue (Carter et al., 2011). enormous potential reserve of energy that it was important to col- There were several decades of history leading up to it that lect the information for future use. -

EMD Shale Gas and Liquids Committee Mid-Year Report, FY 2013

EMD Shale Gas and Liquids Committee Mid-Year Report, FY 2013 Neil S. Fishman, Chair November 8, 2012 Vice Chairs: Brian Cardott, (Vice Chair, Government), Oklahoma Geological Survey, Norman, OK Harris Cander (Vice Chair, Industry), BP, Houston, TX Sven Egenhoff, (Vice Chair, University), Colorado State University Advisory Committee (in alphabetical order): Jeff Aldrich, Dart Energy Ltd., Singapore Kent Bowker, Bowker Petroleum, The Woodlands, TX Ken Chew, IHS (retired), Perthsire, Scotland Thomas Chidsey, Utah Geological Survey, Salt Lake City, UT Russell Dubiel, U.S. Geological Survey, Denver, CO Catherine Enomoto, U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, VA William Harrison, Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo, MI Ursula Hammes, Bureau of Economic Geology, Austin, TX Shu Jiang, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT Margaret Keller, U.S. Geological Survey, Menlo Park, CA Julie LeFever, North Dakota Geological Survey, Grand Forks, ND Peng Li, Arkansas Geological Survey, Little Rock, AR Jock McCracken, Egret Consulting, Calgary, AB Stephen Nordeng, North Dakota Geological Survey, Grand Forks, ND Rich Nyahay, New York Museum, Albany, NY Stephen Sonnenberg, Colorado School of Mines, Golden, CO Rachel Walker, Countrymark Energy Resources, LLC, Indianapolis, IN INTRODUCTION It is a pleasure to present this Mid-Year Report from the EMD Shale Gas and Liquids Committee. This report contains information about specific shales across the U.S., Canada, Europe, China, as well as SE Asia from which hydrocarbons are currently being produced or shales that are of interest for hydrocarbon EMD Shale Gas and Liquids Commitee, Mid-Year Report, November 8, 2012 Page 1 exploitation. New in this report is a section on southeast Asia, in addition to an entire section on China, and an expanded section on Europe.