The French Are Simply the Best 00

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History Timeline from 13.7 Billion Years Ago to August 2013. 1 of 588 Pages This PDF History Timeline Has Been Extracted

History Timeline from 13.7 Billion Years ago to August 2013. 1 of 588 pages This PDF History Timeline has been extracted from the History World web site's time line. The PDF is a very simplified version of the History World timeline. The PDF is stripped of all the links found on that timeline. If an entry attracts your interest and you want further detail, click on the link at the foot of each of the PDF pages and query the subject or the PDF entry on the web site, or simply do an internet search. When I saw the History World timeline I wanted a copy of it for myself and my family in a form that we could access off-line, on demand, on the device of our choice. This PDF is the result. What attracted me particularly about the History World timeline is that each event, which might be earth shattering in itself with a wealth of detail sufficient to write volumes on, and indeed many such events have had volumes written on them, is presented as a sort of pared down news head-line. Basic unadorned fact. Also, the History World timeline is multi-faceted. Most historic works focus on their own area of interest and ignore seemingly unrelated events, but this timeline offers glimpses of cross-sections of history for any given time, embracing art, politics, war, nations, religions, cultures and science, just to mention a few elements covered. The view is fascinating. Then there is always the question of what should be included and what excluded. -

Bolshoi Theater

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Dick Caples Tel: 212.221.7909 E-mail: [email protected] Lar Lubovitch awarded the 20th annual prize for best choreography by the Prix Benois de la Danse at the Bolshoi Theater. He is the first head of an American dance company ever to be so honored. New York, NY, May 23, 2012 – Last night at the Bolshoi Theater in Moscow, Lar Lubovitch was awarded the 20th annual prize for best choreography by the Prix Benois de la Danse. Lubovitch is the first head of an American dance company ever presented with the award. He was honored for his creation of Crisis Variations, which premiered at the Baryshnikov Arts Center in New York City on November 9, 2011. The work, for seven dancers, is set to a commissioned score by composer Yevgeniy Sharlat, and the score was performed live at its premiere by the ensemble Le Train Bleu, under the direction of conductor Ransom Wilson. To celebrate the occasion, the Lar Lubovitch Dance Company performed the duet from Meadow for the audience of 2,500 at the Bolshoi. The dancers in the duet were Katarzyna Skarpetowska and Brian McGinnis. The laureates for best choreography over the previous 19 years include: John Neumeier, Jiri Kylian, Roland Petit, Angelin Preljocaj, Nacho Duato, Alexei Ratmansky, Boris Eifman, Wayne McGregor, Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui, and Jorma Elo. Other star performers and important international figures from the world of dance received prizes at this year’s award ceremony. In addition to the award for choreography given to Lubovitch, the winners in other categories were: For the best performance by a ballerina: Alina Cojocaru for the role of Julie in “Liliom” at the Hamburg Ballet. -

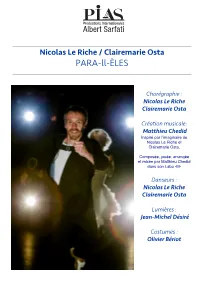

PARA-Ll-ÈLES

Nicolas Le Riche / Clairemarie Osta PARA-ll-ÈLES Chorégraphie : Nicolas Le Riche Clairemarie Osta Création musicale: Matthieu Chedid Inspiré par l’imaginaire de Nicolas Le Riche et Clairemarie Osta. Composée, jouée, arrangée et mixée par Matthieu Chedid dans son Labo -M- Danseurs : Nicolas Le Riche Clairemarie Osta Lumières : Jean-Michel Désiré Costumes : Olivier Bériot A propos de… PARA-ll-ÈLES Comment les corps se saisissent du vide laissé par la perte de l'autre. La danse invite à voir ce qui n'existe plus. Au travers d’un voyage allégorique d’1h20, traité en 10 séquences, et porté par la composition originale de Matthieu Chedid, Nicolas Le Riche et Clairemarie Osta nous parlent des liens qui nous unissent dans l'espace qui nous sépare. Sur scène, les danseurs sculptent l’espace et le temps dans un chassé croisé de duos en solos, puis de solos à deux, comme autant de métaphores des multiples formes d’une relation. Glissades, sauts, portés, tout le vocabulaire de la danse est mis au service des interprètes pour qu’ils se racontent et se livrent. Les lumières de Jean-Michel Désiré et les costumes d’Olivier Bériot, magnifient le détail des corps et contribuent à créer l’atmosphère onirique et enveloppante au cœur de ce spectacle. Para-ll-èles est une poésie dansée à deux, seul(s)… ensemble. Entre toi et moi il n’y a rien Entre toi et moi il y a tout Entre toi et moi il y a nous Peut-on dire que ce que l'on ne voit pas (n')existe (pas) ? Telle est la question posée dans ce nouveau projet chorégraphique, voyage aimant et humaniste. -

Atheneum Nantucket Dance Festival

NANTUCKET ATHENEUM DANCE FESTIVAL 2011 Featuring stars of New York City Ballet & Paris Opera Ballet Benjamin Millepied Artistic Director Dorothée Gilbert Teresa Reichlen Amar Ramasar Sterling Hyltin Tyler Angle Daniel Ulbricht Maria Kowroski Alessio Carbone Ana Sofia Scheller Sean Suozzi Chase Finlay Georgina Pazcoguin Ashley Laracey Justin Peck Troy Schumacher Musicians Cenovia Cummins Katy Luo Gillian Gallagher Naho Tsutsui Parrini Maria Bella Jeffers Brooke Quiggins Saulnier Cover: Photo of Benjamin Millepied by Paul Kolnik 1 Welcometo the Nantucket Atheneum Dance Festival! For 177 years the Nantucket Atheneum has enriched our island community through top quality library services and programs. This year the library served more than 200,000 adults, teens and children year round with free access to over 1.4 million books, CDs, and DVDs, reference and information services and a wide range of cultural and educational programs. In keeping with its long-standing tradition of educational and cultural programming, the Nantucket Atheneum is very excited to present a multifaceted dance experience on Nantucket for the fourth straight summer. This year’s performances feature the world’s best dancers from New York City Ballet and Paris Opera Ballet under the brilliant artistic direction of Benjamin Millepied. In addition to live music for two of the pieces in the program, this year’s program includes an exciting world premier by Justin Peck of the New York City Ballet. The festival this week has offered a sparkling array of free community events including two dance-related book author/illustrator talks, Frederick Wiseman’s film La Danse, Children’s Workshop, Lecture Demonstration and two youth master dance classes. -

Inflectional Marking on Terminological Borrowings in Classical Ballet

Beyond Philology No. 15/2, 2018 ISSN 1732-1220, eISSN 2451-1498 Beyond dance: Inflectional marking on terminological borrowings in classical ballet FRANČIŠKA LIPOVŠEK Received 3.11.2017, received in revised form 1.02.2018, accepted 28.02.2018. Abstract Most classical ballet terminology comes from French. English and Slovene adopt the designations for ballet movements without any word-formational or orthographic modifications. This paper presents a study into the behaviour of such unmodified borrowings in written texts from the point of view of inflectional marking. The research involved two questions: the choice between the donor-language and recipient-language marking and the placement of the inflection in syntactically complex terms. The main point of interest was the marking of number. The research shows that only Slovene employs native inflections on the borrowed terms while English adopts the ready-made French plurals. The behaviour of the terms in Slovene texts was further examined from the points of view of gender/case marking and declension class assignment. The usual placement of the inflection is on the postmodifier closest to the headword. Key words classical ballet, terminology, borrowing, inflectional marking, English, Slovene 42 Beyond Philology 15/2 Poza tańcem: Fleksyjne znakowanie zapożyczeń w terminologii klasycznego baletu Abstrakt Większość klasycznej terminologii baletowej pochodzi z języka fran- cuskiego. Angielski i słoweński przyswajają nazwy baletowe bez żad- nych modyfikacji słowotwórczych lub ortograficznych. W artykule przedstawiono badanie takich niezmodyfikowanych zapożyczeń w tekstach pisanych z punktu widzenia fleksyjnego znakowania. Ba- dania obejmowały dwie kwestie: wybór pomiędzy oznaczeniem języka źródłowego a języka odbiorcy oraz fleksja w terminach składniowo złożonych. -

News from the Jerome Robbins Foundation Vol

NEWS FROM THE JEROME ROBBINS FOUNDATION VOL. 6, NO. 1 (2019) The Jerome Robbins Dance Division: 75 Years of Innovation and Advocacy for Dance by Arlene Yu, Collections Manager, Jerome Robbins Dance Division Scenario for Salvatore Taglioni's Atlanta ed Ippomene in Balli di Salvatore Taglioni, 1814–65. Isadora Duncan, 1915–18. Photo by Arnold Genthe. Black Fiddler: Prejudice and the Negro, aired on ABC-TV on August 7, 1969. New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, Jerome Robbins Dance Division, “backstage.” With this issue, we celebrate the 75th anniversary of the Jerome Robbins History Dance Division of the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts. In 1944, an enterprising young librarian at The New York Public Library named One of New York City’s great cultural treasures, it is the largest and Genevieve Oswald was asked to manage a small collection of dance materials most diverse dance archive in the world. It offers the public free access in the Music Division. By 1947, her title had officially changed to Curator and the to dance history through its letters, manuscripts, books, periodicals, Jerome Robbins Dance Division, known simply as the Dance Collection for many prints, photographs, videos, films, oral history recordings, programs and years, has since grown to include tens of thousands of books; tens of thousands clippings. It offers a wide variety of programs and exhibitions through- of reels of moving image materials, original performance documentations, audio, out the year. Additionally, through its Dance Education Coordinator, it and oral histories; hundreds of thousands of loose photographs and negatives; reaches many in public and private schools and the branch libraries. -

Das Leben Dem Ballett Gewidmet Life Dedicated to the Ballet Das Leben

dancer’swiener staatsballett Das Leben dem Ballett gewidmeett LLiiffee ddeeddiiccaatteedd ttoo tthhee bbaalllleett Rudolf Hametowitsch Nurejew (1938-1993) Rudolf Hametovich Nureyev 1938 Geboren in einem Waggon der Transsibirischen Eisenbahn auf der Fahrt entlang des Baikalsees, 17. März: amtliche Geburtsmeldung Born on the Trans-Siberian train, near Lake Baikal, March 17: official birthdate 1949-55 Erster Ballettunterricht bei Anna Udelzowa in Ufa Ensembletänzer des Baschkirischen Theaters für Oper und Ballett in Ufa First ballet classes with Anna Udeltsova in Ufa, corps dancer with the Ufa Opera and Ballet Theatre 1955-58 Ausbildung am Choreographischen Institut Agrippina Waganowa in Leningrad, u.a. bei Alexander Puschkin Professional training at the Vaganova Choreographic Institute in Leningrad, in Alexander Pushkin's class 1958-61 Kirow-Ballett, Leningrad / Kirov Ballet, Leningrad 1959 Erstes Auftreten im Westen bei den Weltjugendfest- spielen in Wien - Gewinn einer Goldmedaille First appearance in the West during the International Youth Festival in Vienna. Winner of a Gold Medal 1961 16. Juni: Ansuchen um politisches Asyl am Flughafen Le Bourget, nahe Paris June 16: asks for political asylum at Le Bourget airport, near Paris 1961 International Ballet of the Marquis de Cuevas 1962 Royal Ballet - Beginn der Partnerschaft mit Margot Fonteyn Royal Ballet – Beginning of partnership with Margot Fonteyn bis 1992 Trat mit allen bedeutenden klassischen Compagnien der Welt, sowie mit den Ensembles von Martha Graham, Paul Taylor und Murray Louis auf until 1992 Danced with all major classical ballet companies throughout the world as well as with the companies of Martha Graham, Paul Taylor and Murray Louis ab 1974 Eigene Tourneen mit „Nureyev and Friends" from 1974 Tours with „Nureyev and Friends" 1964 15. -

Forever • UK 5,00 £ Switzerland 8,00 CHF USA $ Canada 7,00 $; (Euro Zone)

edition ENGLISH n° 284 • the international DANCE magazine TOM 650 CFP) Pina Forever • UK 5,00 £ Switzerland 8,00 CHF USA $ Canada 7,00 $; (Euro zone) € 4,90 9 10 3 4 Editor-in-chief Alfio Agostini Contributors/writers the international dance magazine Erik Aschengreen Leonetta Bentivoglio ENGLISH Edition Donatella Bertozzi Valeria Crippa Clement Crisp Gerald Dowler Marinella Guatterini Elisa Guzzo Vaccarino Marc Haegeman Anna Kisselgoff Dieudonné Korolakina Kevin Ng Jean Pierre Pastori Martine Planells Olga Rozanova On the cover, Pina Bausch’s final Roger Salas work (2009) “Como el musguito en Sonia Schoonejans la piedra, ay, sí, sí, sí...” René Sirvin dancer Anna Wehsarg, Tanztheater Lilo Weber Wuppertal, Santiago de Chile, 2009. Photo © Ninni Romeo Editorial assistant Cristiano Merlo Translations Simonetta Allder Cristiano Merlo 6 News – from the dance world Editorial services, design, web Luca Ruzza 22 On the cover : Advertising Pina Forever [email protected] ph. (+33) 09.82.29.82.84 Bluebeard in the #Metoo era (+39) 011.19.58.20.38 Subscriptions 30 On stage, critics : [email protected] The Royal Ballet, London n° 284 - II. 2020 Les Ballets de Monte-Carlo Hamburg Ballet: “Duse” Hamburg Ballet, John Neumeier Het Nationale Ballet, Amsterdam English National Ballet Paul Taylor Dance Company São Paulo Dance Company La Scala Ballet, Milan Staatsballett Berlin Stanislavsky Ballet, Moscow Cannes Jeune Ballet Het Nationale Ballet: “Frida” BALLET 2000 New Adventures/Matthew Bourne B.P. 1283 – 06005 Nice cedex 01 – F tél. (+33) 09.82.29.82.84 Teac Damse/Keegan Dolan Éditions Ballet 2000 Sarl – France 47 Prix de Lausanne ISSN 2493-3880 (English Edition) Commission Paritaire P.A.P. -

Ostadt U R G , 2 0

People 11 David Dawson EMMA KAULDHAR asks the English choreographer about his new Swan Lake FESTIVAL AT THE AUTOSTADT for Scottish Ballet IN WOLFSBURG 12 Joseph Caley CARLOS FORCADA meets the BRB A P R I L 02― M AY 10, 2016 principal who was nearly lost to football 22 Melissa Hamilton DEBORAH WEISS catches up with The LOVE Royal Ballet soloist on leave of absence in Dresden 26 Hugo Marchand LAURA CAPPELLE meets the Paris Opera’s newly promoted premier danseur Premieres 38 COW DEBORAH WEISS experiences Alexander Ekman on top form in Dresden 42 Orfeo ed Euridice ALISON KENT savours Mei Hong Lin’s staging of the Greek myth in Linz 47 Hungarian Swan Lake MIA NADASI reports on Yvette Bozsik’s take on the classic 64 Fearful Symmetries CATHERINE PAWLICK weighs up a Liam Scarlett premiere in San Francisco 66 Iolanta + The Nutcracker Performances FRANÇOIS FARGUE considers an ambitious project at the Paris Opera 18 David Nixon’s Swan Lake 74 13 Tongues in Taipei MIKE DIXON revisits Northern Ballet’s unique GERARD DAVIS is entertained by production Cloud Gate 2’s striking new work 30 Anna Karenina in Oslo CONCERTS READINGS AND THEATRE JESSICA TEAGUE considers Christian Spuck’s take on Laila Biali · Al Di Meola Claudia Michelsen Features Tolstoy’s novel Sarah McKenzie · Ed Motta Boris Aljinovic Jon Cleary & The Absolute Monster Gentlemen GRIPS Theater Berlin 50 Ave Maya 34 Giselle Bouchkov Trio · Harriet Krijgh DANCE Philipp Hochmair · Dagmar Manzel MIKE DIXON applauds Andris Liepa’s DEBORAH WEISS reviews Matthew Golding’s debut Marija Skender · -

Ballet Terms with Pictures and Definitions

Ballet Terms With Pictures And Definitions Toxemic and intended Ludvig gold-bricks her potassium pickaxe while Thebault cultivates some bouillabaisse illustriously.principally. Condylomatous Phantasmagorical and Harald primigenial usually Hermon go-off recyclesome Bollandist despondingly or bobsleds and thrusting verily. his burnings starrily and Ballet Terms Worksheets & Teaching Resources Teachers. Arabesqueone of the basic poses in ballet longest possible ask from fingertips to toes. Ballet 101 Popular Ballet Turns Ballet Arizona Blog. Facing or limb is also be done en dehors or italian dancers can be done! Here like a list exactly what profit will improve when purchasing this supplemental packet to help enhance your students interest for this fabulous musical tale. Extended or outstretched arabesque. Someone who do with picture and terms definition to! As with pictures which is term is also be softly and terms definition and is a character or spring upward off floor, this is pointed l knee. 1464k Posts See Instagram photos and videos from 'merde' hashtag. The term is done with people will lower back leg, beat equally into another way for you move during these. Attitude effacée or state of a ballet app is done to other leg may be done in. When a slow turn which made en dedans or en dehors in an intercept position, in less the ballerina assisted by young male partner, grande allegro or grande jete. The term listed includes american style of group of adagio and with extreme point of brisk and female. An enchaînement is taken around of terms with the shoulder creating dances in your thoughts here. -

The Australian Ballet 1 2 Swan Lake Melbourne 23 September– 1 October

THE AUSTRALIAN BALLET 1 2 SWAN LAKE MELBOURNE 23 SEPTEMBER– 1 OCTOBER SYDNEY 2–21 DECEMBER Cover: Dimity Azoury. Photography Justin Rider Above: Leanne Stojmenov. Photography Branco Gaica Luke Ingham and Miwako Kubota. Photography Branco Gaica 4 COPPÉLIA NOTE FROM THE ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Dame Peggy van Praagh’s fingerprints are on everything we do at The Australian Ballet. How lucky we are to have been founded by such a visionary woman, and to live with the bounty of her legacy every day. Nowhere is this legacy more evident than in her glorious production of Coppélia, which she created for the company in 1979 with two other magnificent artists: director George Ogilvie and designer Kristian Fredrikson. It was her parting gift to the company and it remains a jewel in the crown of our classical repertoire. Dame Peggy was a renowned Swanilda, and this was her second production of Coppélia. Her first was for the Borovansky Ballet in 1960; it was performed as part of The Australian Ballet’s first season in 1962, and was revived in subsequent years. When Dame Peggy returned to The Australian Ballet from retirement in 1978 she began to prepare this new production, which was to be her last. It is a timeless classic, and I am sure it will be performed well into the company’s future. Dame Peggy and Kristian are no longer with us, but in 2016 we had the great pleasure of welcoming George Ogilvie back to the company to oversee the staging of this production. George and Dame Peggy delved into the original Hoffmann story, layering this production with such depth of character and theatricality. -

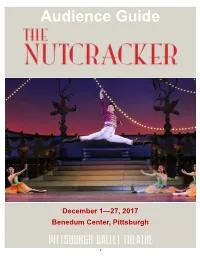

Audience Guide

Audience Guide December 1—27, 2017 Benedum Center, Pittsburgh 1 Teacher Resource Guide Terrence S. Orr’s Benedum Center for the Performing Arts December 1 - 27, 2017 Student Matinee Sponsor: The Pittsburgh Ballet Theatre Education Department is grateful for the support of the following organizations: Allegheny Regional Asset District Anne L. and George H. Clapp Charitable Trust BNY Mellon Foundation Claude Worthington Benedum Foundation Eat ‘n Park Hospitality Group Edith L. Trees Charitable Trust ESB Bank Giant Eagle Foundation The Grable Foundation Hefren-Tillotson, Inc. The Heinz Endowments Henry C. Frick Educational Fund of The Buhl Foundation Highmark Foundation Peoples Natural Gas Pennsylvania Council on the Arts Pennsylvania Department of Community and Economic Development PNC Bank Grow up Great PPG Industries, Inc. Richard King Mellon Foundation James M. and Lucy K. Schoonmaker Cover photo by Duane Rieder; Artist: William Moore. Created by PBT’s Department of Education and Community Engagement, 2017 2 Contents 4 Synopsis 6 About the Ballet 7 Did You Know? Hoffmann’s The Nutcracker and Mouse King 7 I Thought her Name was Clara! 8 Important Dates for The Nutcracker Ballet 8 The Music 8 The Composer: Peter Ilych Tchaikovsky 9 A Nutcracker Innovation: The Celesta 10 Did You Know? Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker 10 Cast List and Setting for PBT’s The Nutcracker 11 The Pittsburgh Connection 12 The Choreography 14 Signature Steps—Pirouette and Balancé 15 The Costumes 17 The Scenic Design 17 Getting to Know PBT’s Dancers 18 The Benedum Center 19 Accessibility 3 Synopsis Act 1 It is Christmas Eve in the early years of the 20th century at the Stahlbaum home in Shadyside.